Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (January 29, 1688 – March 29, 1772) was born as Emanuel Swedberg in Stockholm, Sweden. When his family was ennobled, the name changed to Swedenborg. He was a Swedish scientist, inventor, statesman, traveler, philosopher, biblical scholar, psychic and Christian mystic. He used the word "Theosophy" for his teachings and after his death an organization to publish his works was formed in London in 1784 with the name of Theosophical Society.

Every movement in alternative spirituality – from mental healing to New Age mysticism – owes a debt to the ideas he exploded upon the Western world. [1] He was one of the mystics who has influenced Theosophy, yet he left a far more profound impress on official science. [2]He wrote eighteen different works published in twenty-five volumes, totaling about three and a half million words. [3]

The great theme of his life was to resolve the dichotomy between faith and science. He did not reconcile his science with his religion through some jury-rigged combination of inimical worldviews, but by taking the scientific perspective and moving further and further inward with it, until he reached, as he believed, a transcendent realm of spiritual realities. It is the constant movement inward that furnished the key to both his life and his work. [4]

Early Life

Emanuel Swedenborg was born into a wealthy, religious, and distinguished family, the third child and second son. His father, Jesper Swedberg, was a pious Lutheran pastor, who later became a bishop. His mother, Sara Behm, was the daughter of a wealthy mine owner, a kind and gentle person who died when Emanual was only eight. [5] His eldest brother died shortly after due to the same fever. [6] His home provided him with a firm foundation for his spiritual researches. His father was a prolific writer of hymns and sermons and his thirst for writing left a mark on his son. [7]

Even in his early years he was constantly engaged in thought upon God, salvation and spiritual life. He revealed things to his parents that made them wonder if angels spoke through him. Between the ages of six and twelve he used to delight in talking with clergymen about faith. [8] His father married Sara Bergia (1666-1720) eighteen months after the death of his first wife and she took a great liking to Emanuel. [9]

Swedenborg received a classical education at Uppsala University (starting in 1699 at the age of eleven), but his main interest soon showed itself to be in mechanics and chemistry – an obsession with how things work, and the invention of new mechanical contrivances. Swedenborg had a great love of his native country and a strong desire to serve by bringing Sweden into the modern world of scientific invention and technology. His love of making himself useful was to remain with him and become a key doctrine in the spiritual writings of his mature years. [10]

When his father had to move to Skara where he took up his bishopric, Swedenborg stayed with his older sister Anna and her husband Erik Benzelius, the university’s librarian. Some biographers have seen Benzelius as the first great influence upon Swedenborg after his father and he might have turned his attention to science and technology. [11]

Initial Projects and First Major Works

In 1734 at the age of 46, he published his first major scientific work, The Mineral Kingdom, in three parts. The first part, called The Principia, was a theoretical physical hypothesis of the origin of the material world from an invisible infinite source. The other two parts were mineralogical works. Besides firmly establishing his reputation as a scientist it also showed the depth of his thinking into “causes of things”. The Principia is an application of Neoplatonic emanations of reality coupled with the principles of geometry and dynamics. Swedenborg perceived that for anything to exist it must be continually being created from within itself.[12]

Researches into the Realm of the Soul

In his major work Oeconomia Regni Animalis (Dynamics of the Soul’s Domain) discusses the heart and the blood, which Swedenborg saw as “the complex of all things that exist in the world and the storehouse….of all that exists in the body” as well as the brain, the nervous system, and the soul. </ref> From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 17</ref>

He was concerned with harmonizing this scientific conscience and his religious yearning, he was able to sketch out a system, a picture of the whole, which began to fulfill his purpose. [13]

In this work Swedenborg describes an intricate interrelation among the blood, the cerebrospinal fluid, and the “spirituous fluid”, a subtle substance that constitutes the essence of life. He also sets out a view of the structure of the human soul, which, he argues, consists of a higher intuitive spiritual faculty called the anima; the familiar rational mind, or mens; and the so-called vegetative soul, or animus, which controls vital functions. In a portrait that echoes his later vision of the human soul as a meeting place between the contending forces of hell and heaven, he describes the mens as divided between the higher, heavenly impulses and the coarse physical urges. [14]

Swedenborg further believed that man can choose what he will do; he has free will. Her further argues, that God will compel no man, but if he finds even the faintest spark of reciprocity in man, he can kindle it into the sacred fire. “Granting this, it follows that there is a universal law”. [15]

Spiritual Crisis and turn to Theology

In 1743, in the middle of his life, Swedenborg underwent a spiritual crisis and personal transformation. He had been abroad for several years on one of his many journeys, but now returned home to Sweden, where he had recently acquired property near Stockholm. [16]

This crisis marked the turning point in his life and would lead him to the vocation for which he is most remembers – that of spiritual visionary and sage. He was a devout Christian all his life but attempted to explore the nature of the through scientific methods. The transition in Swedenborg’s intellectual thought appears to have been the result of his own inner experiences. Before the crisis, while writing Dynamics of the Soul’s Domain he observed, as in his childhood when he regulated his psychological state through breath control, how his breath would spontaneously cease when he was contemplating certain matters. He began to record his dreams and spiritual experiences. During these years he didn’t show any outward shift in his inner orientation; he continued to travel and write. [17]

< br>Until this spiritual crisis Swedenborg believed ghat it was through his work in science, either via one of his discoveries or theories, or through one of his inventions, that he would achieve fame, perhaps even immortality. With the events that led to the crisis, however, his aching hunger for recognition – as well as his predilection for women – was seen in a new light. In The Spiritual Diary, a journal Swedenborg kept from 1746 till 1765 and probably the most in-depth and continuous record of “inner experiences” we have, he is at pains to amend his past life. In the early entries, he often refers to himself as a sinner and later he is very critical of himself.[18]

In addition to recording his dreams, Swedenborg had several spiritual experiences and at one point told a friend that he had encountered Lord God, the creator of the world, and the Redeemer and was told to explain the spiritual sense of Scripture. From then on the writings focused on Theological topics, even while keeping his duties with Board of Mines, accepting there eventually the post of councilor. [19]

Of all his theological books Heaven and Hell would become Swedenborg’s most popular work due to the human fascination with the afterlife. The book presents a succinct digest of many of the key elements of Swedenborg’s theology, including his teaching that heaven has the structure of a human being; the doctrine of heavenly marriage; and the idea that the earth is a proving ground for the human soul, which after death gravitates strictly toward whatever its ruling passion was in life and tends toward heaven or toward hell, after an interval in the intermediate world of spirits. [20]

Correspondences

Anyone interested to know how Swedenborg understood the Bible should read Arcana Coelistia. Swedenborg interpreted the Bible in a whole new light. For Swedenborg, the Bible is written in a symbolic code, and its purpose is to depict truths about the spiritual worlds. This code is one of correspondences. The truth about correspondences was known to the ancients, but for us, and for the people of Swedenborg’s time, it is lost. Its essence is that there is a direct, one-to-one link between the elements of our world, both natural and man-made, and the spiritual worlds within. [21] He wrote

“The whole natural world corresponds to the spiritual world – not just the natural world in general, but actually in details. It is vital to understand that the natural world emerges and endures from the spiritual world, just like an effect from the cause that produces it.” [22]

The natural world for Swedenborg means “all the expanse under the sun, receiving warmth and light from it. All the entities that are maintained from this source belong to that world. The spiritual world, in contrast, is heaven. All the things that are in the heavens belong to that world.” [23][24]

But it’s more than mere symbols; “correspondence,” as Swedenborg uses the term, is about a real, dynamic, ongoing relationship between divine love and human love, divine wisdom and human enlightenment. [25]

Swedenborg came to accept that the material world in every aspect is entirely created by the spiritual. Life, for him, was a force emanating from the Divine. The self-willed man, whether in or out of the body, was free to receive this force and turn it into good or into evil. [26]

Last Years and Final Voyage

Swedenborg saw the publication of many books including a commentary on the Revelation of John called Revelation Unveiled. The Book of Revelation, according to Swedenborg, does not allude to empires and kingdoms, but to spiritual dimensions.

By the mid-1760s Swedenborg had begun to attract a following both in Sweden and abroad. His books and his spiritual teachings had spread widely enough to arouse strong allegiances as well as oppositions. He continued to travel and on a trip to London he made the acquaintance of some men who would form the nucleus of the Swedenborgian movement in England. They were instrumental in issuing some of the first editions of Swedenborg’s works in English.

In December 1977 Swedenborg suffered a stroke, which incapacitated him for several weeks and temporarily removed his spiritual sight. It was soon restored, but Swedenborg remained partially paralyzed and began to tell his friends that he was going to depart for the world of spirits soon, in a letter he said it would be on May 29th, 1772. The prophecy proved true. He died at the age of eighty-four and his last words were to the landlady and her housemaid: “I thank you. God bless you.” [27]

Theosophists on Swedenborg

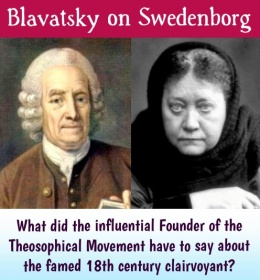

Madame Blavatsky described Swedenborg as “the greatest among the modern seers” but was not sparing with her criticism of him in the areas where she felt criticism was due.

That criticism comes down to three main points:

1) He was never able to rise above his ingrained Christian theology and thus everything he saw was colored by, and interpreted in the light of, Christianity and the Bible.

2) Due to no real fault of his own he was uninitiated and untrained in real spiritual clairvoyance and seership and was thus self-taught and often unable to distinguish between genuine spiritual insight and vivid imagination.

3) Unbeknownst to him, his clairvoyance was largely limited to the astral plane, which is only one level above the physical and which to a large extent is merely the psychic atmosphere of our Earth. [28]

In the October edition of The Theosophist in 1925 the British Theosophist Baseden Butt wrote an article about Swedenborg. He pointed out that all of Swedenborg’s theology is Christo-centric and betrays no indication of having given the idea of reincarnation even cursory attention. But he explains that in spite of these limitations Swedenborg anticipates several doctrines to be found in Theosophy.

Swedenborg had explained that man after death pursues for a time a life similar to that which he has followed in the world—thought, character, personality, and tastes remaining unchanged. Swedenborg refers to the astral plane as the “world of spirits” and the lower and higher mental planes are his “celestial” and “spiritual” heavens. He apparently caught occasional glimpses of the akashic records, for he acquired fragments of occult history that accord with the revelations in Madame Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine and Man: Whence, How and Whither by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater. He reiterates continually the statement that the men of the ‘Ancient’ or Antediluvian Church had an interior “respiration,” whereby they were united to the angels, and could see and converse with spirits, which, of course, was actually the case with the Lemurians.

According to the author of this article, the works of Swedenborg that are most truly in harmony with Theosophy are probably Angelic Wisdom Concerning the Divine Love and Wisdom and Earths in the Universe. In these his thought is less affected by preconceived dogmas. He combines an account of his observations “in the spirit” with profound speculations as to their meaning.

[29][30]

Assessment

Swedenborg’s followers soon assembled themselves into a new denomination, but his legacy extends much further than the New Church. It can be seen in the works of William Blake, Honoré de Balzac, and Charles Baudelaire.

Swedenborg’s life has an architectonic structure to it. On the one hand it encompasses as ascent from an investigation of the mineral kingdom to one of the plant and animal kingdom. When Swedenborg began the age-old quest for the link between the soul and the body, he had to go past reason and rise into the unseen dimension of the spirit. On the other hand, Swedenborg’s journey was also one toward the interior of the self and of the universe. [31]

One might say that Swedenborg in his unremittent emphasis on practical, do-something-about-it, religion was Western and Christian. But he was also, probably without knowing it, and via the Platonists, not far from Hinduism in his worship of God in His Avatar, and he was at one with Buddhism in his insistence on the reality of spiritual law, or Karma. With Buddhism too he believed in the power of the understanding to change wrong feeling to right feeling, so that man would keep the commandments because he “desires to do so”, like a free man and not like a slave. Nor was he far from Dhamma, the Good Law, of Buddha, when he declared in The True Christian Religion: “The Christian world does not yet know that there is an order, and it knows still less what this order is which God introduced into the world at the same time that He created it, and that God cannot act contrary to it, for if he did that, he would be in conflict with himself, for God is that very Order.”[32]

Because Swedenborg claimed to be in contact with angels and spirits, some critics have questioned Swedenborg’s sanity despite an abundance of contemporary reports that he was intelligent, clear-headed, reliable, and kind. There is also independent evidence, reported by multiple witnesses, that supports Swedenborg’s claim. Three incidents in particular caused a stir in his lifetime:

1. While on a visit to the Swedish city of Göteborg, Swedenborg clairvoyantly saw and accurately reported details of a fire simultaneously raging 250 miles away in Stockholm.

2) He helped a widow find a receipt for a substantial sum that a silversmith claimed her husband had never paid, though only the deceased husband could have known its location.

3) In response to a challenge, he confounded Queens Lovisa Ulrike of Sweden by telling her a family secret that she declared no living person could have revealed to him. [33]

In order to publish, preserve, and promote the life-guiding principles of Emanual Swedenborg, a Foundation was established in 1849. The Swedenborg Foundation has a website and anyone interested can explore more of Emanuel Swedenborg’s ideas about this life and the next through a wide selection of printed books and e-books. Their New Century Edition books are available for free download.

A list of his digital works can be found on the website of the Swedenborg Foundation [1] as well as a list of all his Theological writings: [2]

Notes

- ↑ Lachman, Gary. Swedenborg: An Introduction to His Life and Ideas. Penguin Group, New York. 2009. Back page

- ↑ Theosophy.Blavatsky on Swedenborg https://blavatskytheosophy.com/blavatsky-on-swedenborg/. Accessed on 8/25/20

- ↑ Rose, Jonathan. Swedenborg’s Garden of TheologySwedenborg Foundation. 2010. Back Page

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 4

- ↑ Stanley, Michael. Emanuel Swedenborg. Western Esoteric Masters Series.North Atlantic Books, Berkley, Ca. 2003. Introduction

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedbenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 6

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Pages 4-5

- ↑ Trobridge, George. Swedenborg Life and Teaching 5th edition. Swedenberg Foundation, New, York. 1992. Page 3.

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 6

- ↑ Stanley, Michael. Western Esoteric Masters Series: Emanuel SwedenborgNorth Atlantic Books, Berkley, Ca. 2003. Introduction

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 7

- ↑ Stanley, Michael. Western Esoteric Masters Series: Emanuel SwedenborgNorth Atlantic Books, Berkley, Ca. 2003. Introduction

- ↑ Toksvig, Signe. Emanuel Swedenborg. Scientist and Mystic. The Swedenborg Foundation, Inc., New York, N.Y. 1983. Page 113

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Pages 17-18

- ↑ Toksvig, Signe. Emanuel Swedenborg. Scientist and Mystic. The Swedenborg Foundation, Inc., New York, N.Y. 1983. Pages 119-121

- ↑ Rose, Jonathan. Swedenborg’s Garden of Theology. Swedenborg Foundation Press, Westchester, Pa. 2010. Introduction

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Pages 19-20

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. Swedenborg. An Introduction to His Life and Ideas. The Swedenborg Society, 2009. Pages 1-2

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 25

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Pages 31-32

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. Swedenborg. An Introduction to His Life and Ideas. The Swedenborg Society, 2009. Page 111

- ↑ Swedenborg, Heaven and Hell tr. George F. Dole. New York, Swedenborg Foundation, 1984. P. 81 ff

- ↑ Swedenborg, Heaven and Hell tr. George F. Dole. New York, Swedenborg Foundation, 1984. P. 81 ff

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. Swedenborg. An Introduction to His Life and Ideas. The Swedenborg Society, 2009. Page 111

- ↑ Correspondences. Swedenborg Foundation. https://swedenborg.com/emanuel-swedenborg/explore/correspondences/ Accessed on 9/25/20

- ↑ Toksvig, Signe. Emanuel Swedenborg. Scientist and Mystic. The Swedenborg Foundation, Inc., New York, N.Y. 1983. Pages 286-287

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 40-47

- ↑ Theosophy.Blavatsky on Swedenborg https://blavatskytheosophy.com/blavatsky-on-swedenborg/. Accessed on 8/25/20

- ↑ Butt, Baseden. Swedenborg as Theosophist. The Thesophist, October 1925, page 113. https://theosophy.world/sites/default/files/Theosophical%20Publications/The%20Theosophist/1925-10%20to%201926-09/theosophist_v47_n1-n12_oct_1925-sep_1926.pdf Accessed on 10/27/20.

- ↑ Butt, Baseden.Swedenborg as TheosophistEdited from the Theosophist, October 1925. Published 3/3/2012. https://www.theosophyforward.com/index.php/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/525-swedenborg-as-theosophist.html Accessed on 10/27/2020

- ↑ Smoley, Richard. The Inner Journey of Emanuel Swedenborg. From: Emanuel Swedenborg. Essays for the New Century Edition on His Life, Work, and Impact. Swedenborg Foundation, West Chester, Pa. 2005. Page 48

- ↑ Toksvig, Signe. Emanuel Swedenborg. Scientist and Mystic. The Swedenborg Foundation, Inc., New York, N.Y. 1983. Pages 358-359

- ↑ Rose, Jonathan. Swedenborg’s Garden of Theology. Swedenborg Foundation Press, Westchester, Pa. 2010. Page 5

Additional resources

Articles

- Swedenborg, Emanuel at Theosophy World

- About Swedborg at The Swedenborg Society.

- Blavatsky on Swedenborg at Blavatsky Theosophy Group UK