Gustav Mahler: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

<ref>Engel, Gabriel ''Gustav Mahler, Song Symphonist''</ref> | <ref>Engel, Gabriel ''Gustav Mahler, Song Symphonist''</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

In two separate letters to Alma, Mahler mentions his vegetarianism. | |||

<blockquote>"Keussler is also already here. A splendid fellow. After the Saturday evening rehearsal I'll be joining him for a vegetarian meal. (10 September 1908)." <ref>Mahler, Gustav, ''Gustav Mahler: Letters To His Wife'', ed. Henry-Louis de La Grange and Gunther Weiss, (Cornell University Press, 2004) p.254</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

"I'll presumably have to assume the role of 'the flesh pots in the land of Egypt'. Ouch! What a metaphor for a husband with vegetarian inclinations! (June 1909)." <ref>Mahler, Gustav, ''Gustav Mahler: Letters To His Wife'', ed. Henry-Louis de La Grange and Gunther Weiss, (Cornell University Press, 2004) p.272)</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

==Online resources== | ==Online resources== | ||

Revision as of 20:26, 24 December 2014

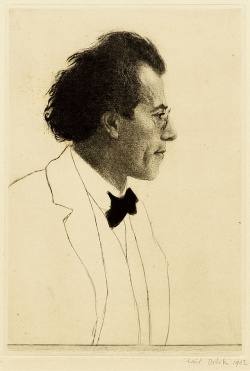

Gustav Mahler (7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was a late-Romantic composer and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer, Mahler acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism of the early 20th century. While in his lifetime his status as a conductor was established beyond question, his own music gained wide popularity only after periods of relative neglect which included a ban on its performance in much of Europe during the Nazi era. After 1945 the music was discovered and championed by a new generation of listeners; Mahler then became a frequently performed and recorded composer, a position he has sustained into the 21st century.

Biography

Gustav Mahler was born to a Jewish family in the village of Kalischt in Bohemia, in what was then the Austrian Empire, now Kaliště in the Czech Republic.

In November 1901, he met Alma Schindler, the stepdaughter of painter Carl Moll, at a social gathering. This meeting led to a rapid courtship; Mahler and Alma were married at a private ceremony on 9 March 1902.

Around Christmas 1910 he began suffering from a sore throat, which persisted. On 21 February 1911, with a temperature of 40 °C (104 °F), Mahler insisted on fulfilling an engagement at Carnegie Hall, After weeks confined to bed he was diagnosed with bacterial endocarditis, a disease to which sufferers from defective heart valves were particularly prone. On 8 April the Mahler family and a permanent nurse left New York on board SS Amerika bound for Europe. They reached Paris ten days later, where Mahler entered a clinic at Neuilly, but there was no improvement; on 11 May he was taken by train to the Lŏw sanatorium in Vienna, where he died on 18 May.

Theosophical involvement

Occultism was thriving in fin-de-siècle Vienna when Mahler was about forty years old.

There was more to turn-of-the-century Vienna than sometimes meets the scholarly eye. In addition to the kinds of figures and topics that tend to reinforce “legitimate” areas of investigation - philosophy, music architecture, and psychoanalysis, for instance – there was an occult underground present in Vienna, as in much of the German-speaking world. This was a world in which Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Pythagoreanism, astrology, clairvoyance, numerology and other forms of occult belief played roles – and at times important roles – in the lives of some of the same figures who appear often in writing about fin-de-siècle Vienna. [1]

In his book, Hammer of the Gods, David Luhrssen includes Mahler as a member of Vienna’s Theosophical Society.

The original membership of Vienna’s Theosophical Society, at its foundation in 1887, was drawn from a coterie of intellectuals and bohemians who had been meeting continually since the end of the 1870s. Friedrich Eckstein (1861-1939), the Society’s first president and later a “gray eminence of Viennese cultural life,” had been presiding over discussions at a table in a Viennese vegetarian restaurant for a decade before the Society was formally organized in Austria’s capital. The circle around Eckstein, who had been Anton Bruckner’s personal secretary, was diverse in ethnic origin and in politics. It included Polish poet Siegfried Lipiner; Jewish symphonic master Gustav Mahler; Austrian composer of German art songs Hugo Wolf; feminist Rosa Mayreder, who discussed gender roles in terms of the alchemical fusion of opposites; Rudolf Steiner, who later established the Waldorf school movement along with a mystical Christian branch of Theosophy called Anthroposophy; and, occasionally, Victor Adler, founder of the Social Democratic Party of Austria. [2]

However, in Modernism's History, Bernard Smith indicates that Alma Mahler became a theosophist in 1914, three years after Mahler’s death, and is credited with introducing Johannes Itten, a Swiss expressionist painter, to Theosophy. Although Mahler had an interest in esotericism, it is not clear if Gustav Mahler himself became a theosophist or was actually a member of the Vienna Theosophical Society.

Johannes Itten (1888-1967), who taught at the Bauhaus from 1919 to 1923, became interested in theosophy after he met Walter Gropius’s first wife Alma Mahler, a theosophist since 1914. He read Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought Forms, Indian Philosophy, and the cabbala and espoused the views of the Mazdaznan [3] sect which insisted on meditation and vegetarianism. [4]

However in the final months before his death, Gustav and Alma did share an interest in theosophical literature.

Mahler fell over himself in his attempts to show Alma his affection. He invited her to Niagara Falls and in general was more charming and attentive then he had been ever before. Initially, at least, these final months were not over shadowed, except by problems with the orchestra. The couple began to take an interest in theosophy and the occult and studied books by C. W. Leadbeater and Annie Besant, the latter a former associate of Helena Blavatsky, that were le dernier cri [5] in Europe and America. [6]

In her book, Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters, Alma Mahler confirms the Mahler Family’s interest in the occult.

I saw a lot of a young American woman who tried to imbue me with the occult. She lent me books by Leadbeater and Mrs. Besant. I always went straight to Mahler the moment she left and repeated word for word all she had said. It was something new in those days and he was interested. We started shutting our eyes to see what colours we could see. We practiced this - and many other rites ordained by occultists – so zealously that Gucki[7] was once discovered walking up and down the room with her eyes shut. When we asked her what she was doing, she replied: “I’m, looking for green.” [8]

John Covac speculates that the Mahlers were reading Leadbeater and Besant’s book Thought Forms.

In the case of this anecdote, the book in question is most likely Leadbeater and Besant’s Thought Forms which discusses the spiritual meanings of colors in enthusiastically Theosophical terms. [9]

Vegetarianism

Mahler’s vegetarianism is documented in his letters.

"The following season proved a very gloomy one for Mahler. Once more the "city of music" could furnish him no greater material consolation than that of a few piano-pupils. Evenings he would attach himself to a group of young, poverty-stricken Wagnerian enthusiasts and over a cup of coffee help wage the abstract battles of the music-dramatist's political and ethical doctrines. Of these sage utterances one the young musicians adopted unanimously was the proposal to regenerate mankind through strict, vegetarian diet. Perhaps the cost of meat-dishes had as much to do with this resolution as the realization that carnivorous humanity was going to the dogs. [...] Although two years had passed since those unforgettable meatless meetings of the young Wagnerians in Vienna, Mahler was in Olmuetz still a vegetarian, claiming bitterly that he went to the restaurant to starve." [10]

In two separate letters to Alma, Mahler mentions his vegetarianism.

"Keussler is also already here. A splendid fellow. After the Saturday evening rehearsal I'll be joining him for a vegetarian meal. (10 September 1908)." [11]

"I'll presumably have to assume the role of 'the flesh pots in the land of Egypt'. Ouch! What a metaphor for a husband with vegetarian inclinations! (June 1909)." [12]

Online resources

References

- ↑ Covach, John, Balzacian Mysticism, Palindromic Design and Heavenly Time in Berg’s Music, Encrypted Messages in Alban Berg's Music, ed. Siglind Bruhn Routledge (New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998)

- ↑ Luhrssen, David, Hammer of the Gods: The Thule Society and the Birth of Nazism (Washington, D.C., Potomac Books Inc., 2012) p.13

- ↑ Mazdaznan was a neo-Zoroastrian religion which held that the Earth should be restored to a garden where humanity can cooperate and converse with God.

- ↑ Smith, Bernard Modernism's History, (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press Ltd., 1998) pp.76-77

- ↑ the newest fashion

- ↑ Fischer, Jens Malte Gustav Mahler, tr. Stewart Spencer(Great Britain: Yale University Press, 2011)

- ↑ Anna Justine Mahler (15 June 1904 – 3 June 1988) was the second child of the composer Gustav Mahler and his wife Alma Schindler. They nicknamed her 'Gucki' on account of her big blue eyes (Gucken is German for 'peek' or 'peep').

- ↑ Mahler, Alma Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters, ed. Donald Mitchell, (New York, Viking Press, 1969), p.188

- ↑ Covach, John, Balzacian Mysticism, Palindromic Design and Heavenly Time in Berg’s Music, Encrypted Messages in Alban Berg's Music, ed. Siglind Bruhn Routledge, New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998, p.7

- ↑ Engel, Gabriel Gustav Mahler, Song Symphonist

- ↑ Mahler, Gustav, Gustav Mahler: Letters To His Wife, ed. Henry-Louis de La Grange and Gunther Weiss, (Cornell University Press, 2004) p.254

- ↑ Mahler, Gustav, Gustav Mahler: Letters To His Wife, ed. Henry-Louis de La Grange and Gunther Weiss, (Cornell University Press, 2004) p.272)