Alexander Scriabin: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Alexander Scriabin was born in Moscow on December 25, 1871, according to the Julian Calendar, or [[January 6]], 1872 in the Gregorian Calendar that is now in use. His family was aristocratic, with a strong tradition of all male members being in the military, but his father, Nikolai Alexandrovich, took a different direction, training as a lawyer and becoming a minor diplomat. | Alexander Scriabin was born in Moscow on December 25, 1871, according to the Julian Calendar, or [[January 6]], 1872 in the Gregorian Calendar that is now in use. His family was aristocratic, with a strong tradition of all male members being in the military, but his father, Nikolai Alexandrovich, took a different direction, training as a lawyer and becoming a minor diplomat. | ||

The family name derives from "skriba" or "scribe," and has been transliterated in many ways - Scriabine, de Scriabine, Skriabin, Skrjabin, Skryabin.<ref>Bowers (1969) | [[File:Scriabin as cadet.jpg|160px|right|thumb|Scriabin as cadet]] | ||

The family name derives from "skriba" or "scribe," and has been transliterated in many ways - Scriabine, de Scriabine, Skriabin, Skrjabin, Skryabin.<ref>Faubion Bowers, ''Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume I'' (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 109-112.</ref> | |||

Nilolai Scriabin married Lyubox Petrovna Shchetinina, a concert pianist, protegée of Anton Rubinstein, and winner of the Great Gold Medal from the Petersburg Conservatory. She died of tuberculosis within months after Alexander's birth. | Nilolai Scriabin married Lyubox Petrovna Shchetinina, a concert pianist, protegée of Anton Rubinstein, and winner of the Great Gold Medal from the Petersburg Conservatory. She died of tuberculosis within months after Alexander's birth. Bowers (1969) Volume I, 105-107.</ref> | ||

Young Alexander's father was mostly absent in diplomatic postings, so the boy, called "Sasha" or "Shurinka," was raised in the household of his grandmother, his great-aunt, and his father's unmarried sister Lyubov Alexandrova Scriabina. The aunt, an amateur pianist, nurtured Sasha's creativity. Even without formal training, Alexander could play complex tunes on the piano by ear. At age seven, he constructed ten toy pianos with strings, sounding boards, working pedals, and moving keys. He read adult literature, designed patterns for needlework, and wrote short plays.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 109-112.</ref> | Young Alexander's father was mostly absent in diplomatic postings, so the boy, called "Sasha" or "Shurinka," was raised in the household of his grandmother, his great-aunt, and his father's unmarried sister Lyubov Alexandrova Scriabina. The aunt, an amateur pianist, nurtured Sasha's creativity. Even without formal training, Alexander could play complex tunes on the piano by ear. At age seven, he constructed ten toy pianos with strings, sounding boards, working pedals, and moving keys. He read adult literature, designed patterns for needlework, and wrote short plays.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 109-112.</ref> | ||

Nikolai Scriabin remarried and had four more sons and a daughter, but his oldest son continued to live with his aunt Lyubov. Alexander attended the Cadet Corps school, and had a difficult time with hazing and bullying until his skill at the piano made him indispensable at social events. He began composing, and began to have formal music lessons during the summers. In 1885, he was began a five-year program of training at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory, learning theory, solfeggio, harmony, and counterpoint.<ref>Bowers | Nikolai Scriabin remarried and had four more sons and a daughter, but his oldest son continued to live with his aunt Lyubov. Alexander attended the Cadet Corps school, and had a difficult time with hazing and bullying until his skill at the piano made him indispensable at social events. He began composing, and began to have formal music lessons during the summers. In 1885, he was began a five-year program of training at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory, learning theory, solfeggio, harmony, and counterpoint.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 141.</ref> In 1892 he began to sell his compositions. | ||

As a youth, and throughout his life, Scriabin was physically small and weak; sensitive and volatile; easily bored; and fragile in health. His right hand was susceptible to strain from overworking it, | As a youth, and throughout his life, Scriabin was physically small and weak; sensitive and volatile; easily bored; and fragile in health. His right hand was susceptible to strain from overworking it, especially after an injury in 1891. He developed an unusually strong and independent left hand technique as a result, and wrote music for the left hand alone.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 150, 182-183.</ref> | ||

=== Marriage and parenthood === | === Marriage and parenthood === | ||

In December, 1893, Scriabin was introduced to '''Vera Ivanovna Isakovich''' (1875-1920), a talented pianist. When he was 25 years old, they married in a formal 5-day Russian Orthodox ceremony from August 15-20, 1897.<ref>Bowers | In December, 1893, Scriabin was introduced to '''Vera Ivanovna Isakovich''' (1875-1920), a talented pianist. When he was 25 years old, they married in a formal 5-day Russian Orthodox ceremony from August 15-20, 1897.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 242.</ref> The couple performed together often - individually, and in arrangements for four hands. They had four children, putting pressure on Scriabin to work at teaching at the Moscow Conservatory in addition to his performances and composing. The family continually struggled to make ends meet. | ||

Scriabin abandoned his family and separated from Vera in 1904. She eventually agreed to a divorce, and he married '''Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer''', with whom he had three more children. They lived in various European cities, in self-imposed exile.<ref>"Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in [http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/music/aleksandr-scriabin/ Russiapedia]. Accessed October 23, 2016.</ref> | Scriabin abandoned his family and separated from Vera in 1904. She eventually agreed to a divorce, and he married '''Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer''', with whom he had three more children. They lived in various European cities, in self-imposed exile.<ref>"Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in [http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/music/aleksandr-scriabin/ Russiapedia]. Accessed October 23, 2016.</ref> | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

=== Later years === | === Later years === | ||

Scriabin visited London in 1914. He wrote on March 24 that he planned to dine with Theosophists, hosted by a man named Weed who had been a secretary of the Society for 32 years. "At his house I will meet the woman in whose arms Blavatsky died. The dinner promises me much."<ref>Bowers | Scriabin visited London in 1914. He wrote on March 24 that he planned to dine with Theosophists, hosted by a man named Weed who had been a secretary of the Society for 32 years. "At his house I will meet the woman in whose arms [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky|[Madame] Blavatsky]] died. The dinner promises me much."<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 258.</ref> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

It was in London that Scriabin became ill. It began with a pimple on his upper lip under his moustache. The pimple was infected with staphylococcus blood poisoning. The illness led to his death. Tatiana and the children were left with little money and Rachmaninov, among others, came to their aid.<ref>"Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in [http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/music/aleksandr-scriabin/ Russiapedia]. Accessed October 23, 2016.</ref> | It was in London that Scriabin became ill. It began with a pimple on his upper lip under his moustache. The pimple was infected with staphylococcus blood poisoning. The illness led to his death. Tatiana and the children were left with little money and Rachmaninov, among others, came to their aid.<ref>"Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in [http://russiapedia.rt.com/prominent-russians/music/aleksandr-scriabin/ Russiapedia]. Accessed October 23, 2016.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

On April 2, 1915, Scriabin performed his final recital in St. Petersburg. He died on [[April 27]], 1915 (or April 14 by Julian Calendar). His friend '''Sergei Rachmaninov''' went on a concert tour devoted to Scriabin's music to raise funds for | On April 2, 1915, Scriabin performed his final recital in St. Petersburg. He died on [[April 27]], 1915 (or April 14 by Julian Calendar). His friend '''Sergei Rachmaninov''' went on a concert tour devoted to Scriabin's music to raise funds for the family. | ||

[[File:Scriabin writing.jpg|200px|right|thumb|Scriabin writing]] | |||

== Musical career == | == Musical career == | ||

Music publisher '''Mitrofan Belaieff''' was Scriabin's mentor and guide in the music world. He supported the composer financially for many years and | Music publisher '''Mitrofan Belaieff''' was Scriabin's mentor and guide in the music world. He supported the composer financially for many years and continually importuned him to complete compositions. Scriabin usually had several musical pieces in various states of incompleteness, and many might never have been published without external pressure. Belaieff could be generous, miserly, petulant, and nurturing in turns to elicit work from the often lazy and distracted composer. | ||

In the first phase of his career, his compositions were much influenced by Chopin. | In the first phase of his career, his compositions were much influenced by the Romantic music of Chopin and Robert Schumann. In his piano concerts, he had the skill to perform any of the musical literature of the day. His technique of touching the keys, his expressiveness, and his sophisticated use of pedals achieved unusual effects. After Scriabin began composing, he mostly performed his own pieces.<ref>Simon Nicholls, "On the track of Scriabin as Pianist" at [http://www.scriabin-association.com/articles/tracks-scriabin-pianist-simon-nicholls/ Scriabin Association website.]</ref> | ||

Pianist Anthony Hewitt recorded all of Scriabin's preludes and wrote of that experience, | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

There are of course many facets and joys in such a project, but one of the aspects I found most fascinating was to trace the development in Scriabin’s style, from lavish romanticism in the early Preludes, to the bleak vulnerability and stark atonality in the later ones. He stretched the boundaries of tonality, and has sadly been given little credit for it. | |||

If there is one element which I found encompasses the whole span of Preludes, irrespective of style, it’s the sense of tonality as a means of conveying colour and mood, and latterly atonality and dissonance playing a key part in communicating a very specific emotion, often one of rage or violence, unresolved tension, and an accompanying mystical element... | |||

By the time we arrive at Opus 48, atonality is becoming the dominant musical language. Interestingly at this juncture, Scriabin stops using metronome markings and tempo indications, replacing them with idiosyncratic directions: “Con Stravaganza”, “Festivamente”, “Poetico con delizio” (poetic and with delight), “Bellicoso” (war-like)... He is very specific in the states of mind needed to capture the spirit... | |||

it’s remarkable to think that Scriabin wrote so many Preludes, all of which are completely different; testament to his limitless imagination.<ref>Anthony Hewitt, "The Development of Dissonance in Scriabin's Piano Preludes" at [http://www.scriabin-association.com/development-dissonance-skryabins-piano-preludes-anthony-hewitt/ Scriabin Association website.]</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Scriabin' | [[File:Scriabin Circle of Fifths.png|240px|right|thumb|Circle of Fifths]] | ||

Scriabin associated colors with musical tones, characteristic of '''synesthesia'''. He developed a color-coded circle of fifths that was influenced by Theosophical thought. The fifth symphony, '''''Prometheus''''', was completed in 1910. It was scored for a large orchestra and chorus, plus a ''clavier à lumières'', a keyboard instrument designed to trigger lights corresponding with certain chords. | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Unfortunately, the ''clavier a lumieres'' existed only in theory when its part was written by Scriabin. The first performance of ''Prometheus'' was given without it in Moscow in 1911, and it wasn't performed with lights until the New York concert in | Unfortunately, the ''clavier a lumieres'' existed only in theory when its part was written by Scriabin. The first performance of ''Prometheus'' was given without it in Moscow in 1911, and it wasn't performed with lights until the New York concert in 1915. Even then the lights were just projected on a screen which is not what Scriabin had in mind. He had wanted powerful flashing colors to fill the concert hall and dazzling, almost blinding white light at the climactic end.<ref>Gary Brown, "Music as Magic: Composer Alexander Scriabin" ''The American Theosophist'' 70.5 (May 1982), 157.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

At the time of his death in 1915, he was working on his most ambitious composition - the ''''' | At the time of his death in 1915, he was working on his most ambitious composition - the '''''Mysterium'''''. His goal was no less than the spiritual growth and even enlightenment of the audience in a performance that would take place for seven days.: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Scriabin | For Scriabin, it was precisely the ecstatic, Dionysian powers of music that he conjured in his symphonic works like ''Poem of Fire'' (1909 -10) and ''Poem of Ecstacy'' (1917) that were of most importance. Scriabin developed a “mystic chord” of superimposed fourths and, like Wagner, believed in the “total art work.” He saw music as a means of transforming humanity by hurrying on its spiritual evolution. His last years were spent in planning a gargantuan Mystery drama, combining music, dance, theatre, poetry, ritual, and even incense in an attempt to create a synthesis of the sensual and spiritual and inaugurate a New Age. Scriabin’s “Mystery” was to be performed in a hemispherical temple in India, inducing a supreme ecstasy that would dissolve the physical plane and start a metaphysical chain reaction eventually enveloping the world. Scriabin introduced many Theosophical ideas into his compositions and also experimented with “synesthesia,” the strange experience of “hearing colors” and “seeing music,” going so far as to devise a organ that would project different colored lights that he associated hermetically with different notes and chords.<ref>Gary Lachman, "Concerto for Magic and Mysticism: Esotericism and Western Music." ''The Quest'' 90.4 (July-August, 2002), 132-137.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

The composer was held in high esteem during his lifetime both as a pianist and for his compositions. Today his work can be viewed as a transition from the Romantic Period into the 20th century. English composer [[Cyril Scott]], a Theosophist, offered another perspective of Scriabin's music: | The composer was held in high esteem during his lifetime both as a pianist and for his compositions. He won the prestigious and lucrative '''Glinka Award''' in 1898, 1899, 1900, and 1903.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I,261, 272, 304.</ref>Today his work can be viewed as a transition from the Romantic Period into the 20th century. English composer [[Cyril Scott]], a Theosophist, offered another perspective of Scriabin's music: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Various forms of pantheism, including Eastern religions and theosophy, propose that nature has an indwelling intelligence. Scriabin's harmonic system, especially ''Prometheus'', therefore has an almost inhuman quality about it. Scott says that Scriabin was not under the supervision and protection of a spiritual teacher and that his mysterious death from a pimple was due to his inability to handle the strain he was under from contacting the higher intelligence of nature.<ref>Cyril Scott, ''Music: Its Secret Influence Throughout the Ages'' (New York: Samuel Weiser Inc., 1958).</ref> | Various forms of pantheism, including Eastern religions and theosophy, propose that nature has an indwelling intelligence. Scriabin's harmonic system, especially ''Prometheus'', therefore has an almost inhuman quality about it. Scott says that Scriabin was not under the supervision and protection of a spiritual teacher and that his mysterious death from a pimple was due to his inability to handle the strain he was under from contacting the higher intelligence of nature.<ref>Cyril Scott, ''Music: Its Secret Influence Throughout the Ages'' (New York: Samuel Weiser Inc., 1958).</ref> | ||

| Line 70: | Line 80: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Scriabin wrote in May, 1905 to a friend that "''La Clef la Théosophie'' is a remarkable book. You will be astonished at how close it is to my thinking."<ref>Bowers(1969) | Scriabin wrote in May, 1905 to a friend that "''La Clef la Théosophie'' is a remarkable book. You will be astonished at how close it is to my thinking."<ref>Bowers(1969) Volume II, 52.</ref> He began to blend together Theosophical concepts with the native symbolism of the Russian Silver Age artists and writers as he wrote expressive directions for works such as the ''Preparatory Act'' of the ''Mysterium''.<ref>Richard E. Overill, ''Alexander Scriabin’s Use of French Directions to the Pianist'' at [http://www.scriabin-association.com/articles/alexander-scriabins-use-of-french-directions-to-the-pianist/ Scriabin Association web page].</ref> | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

[In 1906] Scriabin's conversations were full of theosophy and the personality of Blavatsky. he wanted to return to Russia where Theosophy had even more of a vogue than abroad. Even with the exposure of Blavatsky's occultism, which appeared headlined in every newspaper of the world, Scriabin was "unshaken... He attributed the exposés to personal grievances on the part of one member or other in the Theosophical movement."<ref>Bowers (1969) | [In 1906] Scriabin's conversations were full of theosophy and the personality of Blavatsky. he wanted to return to Russia where Theosophy had even more of a vogue than abroad. Even with the exposure of Blavatsky's occultism, which appeared headlined in every newspaper of the world, Scriabin was "unshaken... He attributed the exposés to personal grievances on the part of one member or other in the Theosophical movement."<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume II, 117.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

James Cousins wrote of "Sacha Scriabine of Russia who died in 1915 before he could complete his ambition of setting ''The Secret Doctrire'' to music (not literally but in spirit)."<ref>James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." ''The Theosophist''47.3 (December 1925), 396.</ref> | [[James Cousins]] wrote of "Sacha Scriabine of Russia who died in 1915 before he could complete his ambition of setting ''The Secret Doctrire'' to music (not literally but in spirit)."<ref>James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." ''The Theosophist''47.3 (December 1925), 396.</ref> | ||

[[File:Prometheus Symphony art.jpg|right| | Simon Nicholls, editor of an Oxford University Press book on the composer, wrote " Indeed Skryabin was deeply interested by Mme Blavatsky’s ideas for the last ten years of his life. I have sat in the Skryabin Museum in Moscow and looked at one of the volumes of The Secret Doctrine in the French version, with Skryabin’s carefully ruled underlinings and pencilled comments, many of them."<ref>Simon Nicholls email to Leslie Price and Janet Kerschner. July 19, 2017.</ref> | ||

[[File:Prometheus Symphony art.jpg|right|260px|right|thumb|Cover by Jean Delville for ''Prometheus'' symphony]] | |||

== Theosophical influence in ''Prometheus'' symphony == | == Theosophical influence in ''Prometheus'' symphony == | ||

| Line 86: | Line 98: | ||

[[James Cousins|Dr. James Cousins]] wrote an account of how this symphony written, that he heard while visiting the composer with his wife [[Margaret Cousins]], in the suburbs of Brussels: | [[James Cousins|Dr. James Cousins]] wrote an account of how this symphony written, that he heard while visiting the composer with his wife [[Margaret Cousins]], in the suburbs of Brussels: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

When Scriabine was a very young man, already noted as a composer and pianist, he went to Brussels, and there, among the younger group of artists in various mediums, he met Jean Delville. The two were attracted to one another. Scriabine noticed something in Delville that he himself lacked: Scriabine was groping towards some kind of comprehension of life. He asked Delville, in the same room where we heard the story, what was behind his attitude to life, and how he, the questioner, could reach a similar attitude. Delville produced two large volumes and put them before Scriabine. "Read these - and then set them to music," he said. Scriabine read the books - ''The Secret Doctrine''. He went on fire with their revelation. The result was his immortal masterpiece, "Prometheus."... While Scriabine composed the Symphony, he came excitedly at intervals into Delville's drawing-room and played for the painter the musical ideas that were crowding in on him. At the same time Delville painted his wonderful picture of Prometheus falling from the sky with the gift of fire for the earth. He showed us the great canvas in his studio. It almost came to India. [i.e. to the Theosophical Society headquarters in Adyar.]<ref>"Scriabine and Delville," ''The Theosophist'' 57.4 (January 1936), 358.</ref> | When Scriabine was a very young man, already noted as a composer and pianist, he went to Brussels, and there, among the younger group of artists in various mediums, he met [[Jean Delville]]. The two were attracted to one another. Scriabine noticed something in Delville that he himself lacked: Scriabine was groping towards some kind of comprehension of life. He asked Delville, in the same room where we heard the story, what was behind his attitude to life, and how he, the questioner, could reach a similar attitude. Delville produced two large volumes and put them before Scriabine. "Read these - and then set them to music," he said. Scriabine read the books - ''The Secret Doctrine''. He went on fire with their revelation. The result was his immortal masterpiece, "Prometheus."... While Scriabine composed the Symphony, he came excitedly at intervals into Delville's drawing-room and played for the painter the musical ideas that were crowding in on him. At the same time Delville painted his wonderful picture of Prometheus falling from the sky with the gift of fire for the earth. He showed us the great canvas in his studio. It almost came to India. [i.e. to the Theosophical Society headquarters in Adyar.]<ref>"Scriabine and Delville," ''The Theosophist'' 57.4 (January 1936), 358.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| Line 95: | Line 107: | ||

''Prometheus'' as a plot reeks of Theosophical symbolism and is Scriabin's only composition so heavily inflated with such paraphernalia. It exhales Brussels and the dense, mystical air of that city. Delville's cover design for the score shows a lyre ("the World," symbolized by music) rising from a lotus bloom ("the Womb," mind or Asia). In the center over the Star of David is Prometheus's face ("really the ancient symbol of Lucifer," Scriabin said, encompassing all religions). Delville, and perhaps Scriabin, had joined a secret cult within Theosophy called "Sons of the Flames of Wisdom." They worshiped Prometheus, because those fires, colors, lights were metasymbols of man's highest thoughts. Fire was Prometheus's stolen gift to man, and it lay deep within hearts... | ''Prometheus'' as a plot reeks of Theosophical symbolism and is Scriabin's only composition so heavily inflated with such paraphernalia. It exhales Brussels and the dense, mystical air of that city. Delville's cover design for the score shows a lyre ("the World," symbolized by music) rising from a lotus bloom ("the Womb," mind or Asia). In the center over the Star of David is Prometheus's face ("really the ancient symbol of Lucifer," Scriabin said, encompassing all religions). Delville, and perhaps Scriabin, had joined a secret cult within Theosophy called "Sons of the Flames of Wisdom." They worshiped Prometheus, because those fires, colors, lights were metasymbols of man's highest thoughts. Fire was Prometheus's stolen gift to man, and it lay deep within hearts... | ||

To Scriabin, Prometheus had further symbolism beyond Theosophy's haziness. Lucifer was the "Light Bringer," according to the Christian Bible, and Satan was the "Disobedient Rebel." Sabaneeff's program notes... state that "Prometheus, Satanas, and Lucifer all meet in ancient myth. They represent the active energy of the universe, its creative principle. The fire is light, life, struggle, increase, abundance, and thought. At first, this powerful force manifests itself wearily, as languid thirsting for life. Within this lassitude then appears the primordial polarity between soul and matter. Later it does battle and conquers matter - of which it itself is a mere atom - and returns to the original quiet and tranquillity ... thus completing the cycle..."<ref>Bowers (1969) | To Scriabin, Prometheus had further symbolism beyond Theosophy's haziness. [[Lucifer]] was the "Light Bringer," according to the Christian Bible, and Satan was the "Disobedient Rebel." Sabaneeff's program notes... state that "Prometheus, Satanas, and Lucifer all meet in ancient myth. They represent the active energy of the universe, its creative principle. The fire is light, life, struggle, increase, abundance, and thought. At first, this powerful force manifests itself wearily, as languid thirsting for life. Within this lassitude then appears the primordial polarity between soul and matter. Later it does battle and conquers matter - of which it itself is a mere atom - and returns to the original quiet and tranquillity ... thus completing the cycle..."<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume II, 206-207.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

== Musical compositions == | == Musical compositions == | ||

Most of Scriabin's work was for piano in the usual forms - études, preludes, nocturnes, sonatas, mazurkas, etc. His orchestral works are fewer, but among the most popular. For a complete list, see [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_compositions_by_Alexander_Scriabin#Orchestral_works List of compositions by Alexander Scriabin]. Here are some | Most of Scriabin's work was for piano in the usual forms - études, preludes, nocturnes, sonatas, mazurkas, etc. His orchestral works are fewer, but among the most popular. | ||

Kurt Leland writes, | |||

<blockquote> | |||

Among Scriabin’s mystically inclined works for orchestra are the '''''Poem of Ecstasy''''', which depicts the union of male and female principles that continually recreates the universe... | |||

Scriabin also composed ten piano sonatas, several of which have Theosophical subtexts. The Fourth Sonata is about flight toward a star, as in the experience of astral projection. The Seventh, subtitled ''White Mass'', is about the mystical forces unleashed in a magical ceremony, and the Ninth (''Black Mass'') is about purging the corresponding dark forces. The Eighth Sonata uses five musical fragments to represent the constant interplay of the elements earth, water, air, fire, and, as he called it, “the mystical ether.” | |||

Scriabin’s Tenth Sonata portrays solar insects “born from the sun,” “the sun’s kisses.” The radiant halo of trills with which the piece closes is one of the most effective depictions in music of the inner light associated with high [[Meditation|meditative states]], such as samadhi.<ref>Kurt Leland, "Theosophical Music" ''Quest'' 99.2 (Spring, 2011): 61-64. Available at [https://www.theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/2303 ''Quest'' website.]</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

For a complete list of the composer's works, see [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_compositions_by_Alexander_Scriabin#Orchestral_works List of compositions by Alexander Scriabin]. Here are some favorites: | |||

=== Orchestral works === | === Orchestral works === | ||

| Line 107: | Line 130: | ||

* ''Symphonic Poem in D minor''. 1896. | * ''Symphonic Poem in D minor''. 1896. | ||

* ''Piano Concerto in F-sharp minor'', Op. 20. 1896. | * ''Piano Concerto in F-sharp minor'', Op. 20. 1896. | ||

* ''Symphony No. 1 in E major'', Op. 26. | * ''Symphony No. 1 in E major'', Op. 26. 1900. | ||

* ''Symphony No. 2 in C minor'', Op. 29. | * ''Symphony No. 2 in C minor'', Op. 29. 1901. | ||

* ''Symphony No. 3 in C minor'', Op. 43. ''The Divine Poem''. | * ''Symphony No. 3 in C minor'', Op. 43. ''The Divine Poem''. 1904. | ||

* ''The Poem of Ecstasy'', Op. 54. Fourth Symphony. 1908. | * ''The Poem of Ecstasy'', Op. 54. Fourth Symphony. 1908. | ||

* ''Prometheus: The Poem of Fire'', Op. 60. Fifth Symphony. 1910. | * ''Prometheus: The Poem of Fire'', Op. 60. Fifth Symphony. 1910. | ||

=== Piano works === | === Piano works === | ||

* ''Étude in C-sharp minor, No. 1 from Trois morceaux'', Op. 2 | * ''Étude in C-sharp minor, No. 1 from Trois morceaux'', Op. 2. 1887. | ||

* ''12 Études'', Op. 8. 1894. | * ''12 Études'', Op. 8. 1894. | ||

* ''8 Études'', Op. 42. 1903. | * ''8 Études'', Op. 42. 1903. | ||

* ''Fantaisie in B minor'', Op. 28. | * ''Fantaisie in B minor'', Op. 28. 1900. Sonata form. | ||

* ''Impromptu à la Mazur in C major, No. 3 from Trois morceaux'', Op. 2. | * ''Impromptu à la Mazur in C major, No. 3 from Trois morceaux'', Op. 2. | ||

* ''Vers la flamme'', Op. 72. | * ''Vers la flamme'', Op. 72. | ||

| Line 126: | Line 149: | ||

== Scriabin Museum == | == Scriabin Museum == | ||

The '''Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum''' was established on July 17, 1922 to preserve the apartment where the composer lived for his final three years, in an old mansion on Arbat Street in Moscow. The composer's prized possessions were carefully restored, including '''his copy of ''The Secret Doctrine'''''.<ref>Bowers(1969), 87.</ref> The museum preserves Scriabin's library, letters, sheet music, and other items. | The '''Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum''' was established on July 17, 1922 to preserve the apartment where the composer lived for his final three years, in an old mansion on Arbat Street in Moscow. The composer's prized possessions were carefully restored, including '''his copy of ''The Secret Doctrine'''''.<ref>Bowers (1969) Volume I, 87.</ref> The museum preserves Scriabin's library, letters, sheet music, and other items. | ||

== Additional resources == | == Additional resources == | ||

| Line 132: | Line 155: | ||

The [[Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals]] lists articles '''[http://www.austheos.org.au/cgi-bin/ui-csvsearch.pl?search=scriabin about Scriabin]'''. | The [[Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals]] lists articles '''[http://www.austheos.org.au/cgi-bin/ui-csvsearch.pl?search=scriabin about Scriabin]'''. | ||

* [http://www.khaldea.com/charts/scriabin.shtml Alexander Scriabin Natal Horoscope] at Khaldea. | |||

* [https://blavatskynews2.blogspot.de/2016/12/blavatsky-scriabin-and-music.html Blavatsky, Scriabin and Music] at Blavatsky News 2.0 | |||

* [https://www.theosophy.world/encyclopedia/scriabin-alexandre-nikolaevich Scriabin, Alexandre Nikolaevich] to Theosophy World. | |||

* Hull, A. Eaglefield. ''Scriabin''. London: Kegan Paul, 1927. | * Hull, A. Eaglefield. ''Scriabin''. London: Kegan Paul, 1927. | ||

* Sabbagh, Peter. ''The Development of Harmony in Scriabin's Works''. 2003. | * Sabbagh, Peter. ''The Development of Harmony in Scriabin's Works''. 2003. | ||

* Skryabin, Alexander. ''The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Translated by Simon Nicholls and Michael Pushkin, with annotations and comment by Simon Nicholls and foreword by Vladimir shkenazy. | |||

* Swan, Alfred J. ''Scriabin''. London: John Lane, 1923. | * Swan, Alfred J. ''Scriabin''. London: John Lane, 1923. | ||

* Warner, Sybil Marguerite. [http://www.theosophyforward.com/articles/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/503-scriabin-musician-and-theosophist "Scriabin: Musician and Theosophist"] in ''Theosophy Forward''. December 2, 2011. Edited and slightly expanded from Music and Listeners, by Sybil Marguerite Warner, with a foreword by C. Jinarajadasa (London: Service Magazine and Publications, 1911). | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 144: | Line 172: | ||

[[Category:Famous people|Scriabin, Alexander]] | [[Category:Famous people|Scriabin, Alexander]] | ||

[[Category:Nationality Russian|Scriabin, Alexander]] | [[Category:Nationality Russian|Scriabin, Alexander]] | ||

[[Category:People|Scriabin, Alexander]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:31, 21 November 2023

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (Russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Скря́бин) was a Russian pianist and composer who was much influenced by Theosophy and by the Symbolist movement in the visual arts.

Theosophist Margaret Cousins, a concert pianist, wrote: "His music has constantly in it a most poignant sweet quality which seems to pierce to the holy of holies of one's being."[1]

Personal life

Childhood and education

Alexander Scriabin was born in Moscow on December 25, 1871, according to the Julian Calendar, or January 6, 1872 in the Gregorian Calendar that is now in use. His family was aristocratic, with a strong tradition of all male members being in the military, but his father, Nikolai Alexandrovich, took a different direction, training as a lawyer and becoming a minor diplomat.

The family name derives from "skriba" or "scribe," and has been transliterated in many ways - Scriabine, de Scriabine, Skriabin, Skrjabin, Skryabin.[2]

Nilolai Scriabin married Lyubox Petrovna Shchetinina, a concert pianist, protegée of Anton Rubinstein, and winner of the Great Gold Medal from the Petersburg Conservatory. She died of tuberculosis within months after Alexander's birth. Bowers (1969) Volume I, 105-107.</ref>

Young Alexander's father was mostly absent in diplomatic postings, so the boy, called "Sasha" or "Shurinka," was raised in the household of his grandmother, his great-aunt, and his father's unmarried sister Lyubov Alexandrova Scriabina. The aunt, an amateur pianist, nurtured Sasha's creativity. Even without formal training, Alexander could play complex tunes on the piano by ear. At age seven, he constructed ten toy pianos with strings, sounding boards, working pedals, and moving keys. He read adult literature, designed patterns for needlework, and wrote short plays.[3]

Nikolai Scriabin remarried and had four more sons and a daughter, but his oldest son continued to live with his aunt Lyubov. Alexander attended the Cadet Corps school, and had a difficult time with hazing and bullying until his skill at the piano made him indispensable at social events. He began composing, and began to have formal music lessons during the summers. In 1885, he was began a five-year program of training at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory, learning theory, solfeggio, harmony, and counterpoint.[4] In 1892 he began to sell his compositions.

As a youth, and throughout his life, Scriabin was physically small and weak; sensitive and volatile; easily bored; and fragile in health. His right hand was susceptible to strain from overworking it, especially after an injury in 1891. He developed an unusually strong and independent left hand technique as a result, and wrote music for the left hand alone.[5]

Marriage and parenthood

In December, 1893, Scriabin was introduced to Vera Ivanovna Isakovich (1875-1920), a talented pianist. When he was 25 years old, they married in a formal 5-day Russian Orthodox ceremony from August 15-20, 1897.[6] The couple performed together often - individually, and in arrangements for four hands. They had four children, putting pressure on Scriabin to work at teaching at the Moscow Conservatory in addition to his performances and composing. The family continually struggled to make ends meet.

Scriabin abandoned his family and separated from Vera in 1904. She eventually agreed to a divorce, and he married Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer, with whom he had three more children. They lived in various European cities, in self-imposed exile.[7]

Later years

Scriabin visited London in 1914. He wrote on March 24 that he planned to dine with Theosophists, hosted by a man named Weed who had been a secretary of the Society for 32 years. "At his house I will meet the woman in whose arms [Madame] Blavatsky died. The dinner promises me much."[8]

It was in London that Scriabin became ill. It began with a pimple on his upper lip under his moustache. The pimple was infected with staphylococcus blood poisoning. The illness led to his death. Tatiana and the children were left with little money and Rachmaninov, among others, came to their aid.[9]

On April 2, 1915, Scriabin performed his final recital in St. Petersburg. He died on April 27, 1915 (or April 14 by Julian Calendar). His friend Sergei Rachmaninov went on a concert tour devoted to Scriabin's music to raise funds for the family.

Musical career

Music publisher Mitrofan Belaieff was Scriabin's mentor and guide in the music world. He supported the composer financially for many years and continually importuned him to complete compositions. Scriabin usually had several musical pieces in various states of incompleteness, and many might never have been published without external pressure. Belaieff could be generous, miserly, petulant, and nurturing in turns to elicit work from the often lazy and distracted composer.

In the first phase of his career, his compositions were much influenced by the Romantic music of Chopin and Robert Schumann. In his piano concerts, he had the skill to perform any of the musical literature of the day. His technique of touching the keys, his expressiveness, and his sophisticated use of pedals achieved unusual effects. After Scriabin began composing, he mostly performed his own pieces.[10]

Pianist Anthony Hewitt recorded all of Scriabin's preludes and wrote of that experience,

There are of course many facets and joys in such a project, but one of the aspects I found most fascinating was to trace the development in Scriabin’s style, from lavish romanticism in the early Preludes, to the bleak vulnerability and stark atonality in the later ones. He stretched the boundaries of tonality, and has sadly been given little credit for it.

If there is one element which I found encompasses the whole span of Preludes, irrespective of style, it’s the sense of tonality as a means of conveying colour and mood, and latterly atonality and dissonance playing a key part in communicating a very specific emotion, often one of rage or violence, unresolved tension, and an accompanying mystical element...

By the time we arrive at Opus 48, atonality is becoming the dominant musical language. Interestingly at this juncture, Scriabin stops using metronome markings and tempo indications, replacing them with idiosyncratic directions: “Con Stravaganza”, “Festivamente”, “Poetico con delizio” (poetic and with delight), “Bellicoso” (war-like)... He is very specific in the states of mind needed to capture the spirit...

it’s remarkable to think that Scriabin wrote so many Preludes, all of which are completely different; testament to his limitless imagination.[11]

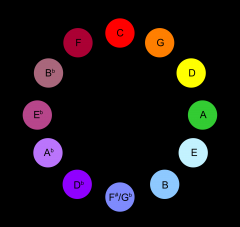

Scriabin associated colors with musical tones, characteristic of synesthesia. He developed a color-coded circle of fifths that was influenced by Theosophical thought. The fifth symphony, Prometheus, was completed in 1910. It was scored for a large orchestra and chorus, plus a clavier à lumières, a keyboard instrument designed to trigger lights corresponding with certain chords.

Unfortunately, the clavier a lumieres existed only in theory when its part was written by Scriabin. The first performance of Prometheus was given without it in Moscow in 1911, and it wasn't performed with lights until the New York concert in 1915. Even then the lights were just projected on a screen which is not what Scriabin had in mind. He had wanted powerful flashing colors to fill the concert hall and dazzling, almost blinding white light at the climactic end.[12]

At the time of his death in 1915, he was working on his most ambitious composition - the Mysterium. His goal was no less than the spiritual growth and even enlightenment of the audience in a performance that would take place for seven days.:

For Scriabin, it was precisely the ecstatic, Dionysian powers of music that he conjured in his symphonic works like Poem of Fire (1909 -10) and Poem of Ecstacy (1917) that were of most importance. Scriabin developed a “mystic chord” of superimposed fourths and, like Wagner, believed in the “total art work.” He saw music as a means of transforming humanity by hurrying on its spiritual evolution. His last years were spent in planning a gargantuan Mystery drama, combining music, dance, theatre, poetry, ritual, and even incense in an attempt to create a synthesis of the sensual and spiritual and inaugurate a New Age. Scriabin’s “Mystery” was to be performed in a hemispherical temple in India, inducing a supreme ecstasy that would dissolve the physical plane and start a metaphysical chain reaction eventually enveloping the world. Scriabin introduced many Theosophical ideas into his compositions and also experimented with “synesthesia,” the strange experience of “hearing colors” and “seeing music,” going so far as to devise a organ that would project different colored lights that he associated hermetically with different notes and chords.[13]

The composer was held in high esteem during his lifetime both as a pianist and for his compositions. He won the prestigious and lucrative Glinka Award in 1898, 1899, 1900, and 1903.[14]Today his work can be viewed as a transition from the Romantic Period into the 20th century. English composer Cyril Scott, a Theosophist, offered another perspective of Scriabin's music:

Various forms of pantheism, including Eastern religions and theosophy, propose that nature has an indwelling intelligence. Scriabin's harmonic system, especially Prometheus, therefore has an almost inhuman quality about it. Scott says that Scriabin was not under the supervision and protection of a spiritual teacher and that his mysterious death from a pimple was due to his inability to handle the strain he was under from contacting the higher intelligence of nature.[15]

Theosophical Society connections

A young friend the Viscount de Gissac asked Scriabin to lecture and write in French, but the composer declined, claiming that his knowledge of French was insufficient. Studying Theosophical literature in French improved his proficiency, so that eventually Scriabin used French notation in his musical compositions.

In Paris in early 1905, de Gissac gave Scriabin a copy of La Clef de la Théosophie, the French translation of Helena Blavatsky’s book The Key to Theosophy (1889) which Scriabin described in a letter of April/May 1905 as a remarkable book and astonishingly close to his own thinking. From that time on, more and more of Scriabin’s circle of friends were drawn from the French and Belgian branches of the Theosophical Society, most notably the painter Jean Delville with whom Scriabin became associated when he relocated to Brussels in 1908. It has been suggested that Scriabin enrolled into formal membership of its Belgian branch at this time, and that Delville may have introduced him to the Sons of the Flames of Wisdom, a secret Promethean cult within Theosophy, but solid documentary evidence for this has yet be produced. Both Leonid Sabaneev and Boris Schloezer later recalled that a French translation of Blavatsky’s book The Secret Doctrine (1888) was always on Scriabin’s work table. It was clear that Scriabin had studied La Doctrine Secrète with great care as he had annotated and underlined in pencil what he considered to be the most important passages. Scriabin also subscribed to Le Lotus Bleu, a monthly francophone theosophical journal, during the period 1904–9 inclusive; this observation can help to account for the presence of the expressive French musical directions in Le Divin Poème, Op.43 (1904). Taken altogether, it is clear that Scriabin carefully studied a very considerable amount of theosophical literature in French during 1904–1909 while he was resident outside Russia, and this would undoubtedly have improved his capacity to express his esoteric, occultist and mystical intentions for his music.

... In addition to the two French texts by Blavatsky and the monthly copies of Le Lotus Bleu mentioned above, Scriabin also had French translations of Auguste Barth’s The Religions of India and Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia in his bookcase. Furthermore, from 1911 onwards in Moscow Scriabin subscribed to three theosophical journals including the francophone monthly periodical Revue Théosophique Belge.[16]

Scriabin wrote in May, 1905 to a friend that "La Clef la Théosophie is a remarkable book. You will be astonished at how close it is to my thinking."[17] He began to blend together Theosophical concepts with the native symbolism of the Russian Silver Age artists and writers as he wrote expressive directions for works such as the Preparatory Act of the Mysterium.[18]

[In 1906] Scriabin's conversations were full of theosophy and the personality of Blavatsky. he wanted to return to Russia where Theosophy had even more of a vogue than abroad. Even with the exposure of Blavatsky's occultism, which appeared headlined in every newspaper of the world, Scriabin was "unshaken... He attributed the exposés to personal grievances on the part of one member or other in the Theosophical movement."[19]

James Cousins wrote of "Sacha Scriabine of Russia who died in 1915 before he could complete his ambition of setting The Secret Doctrire to music (not literally but in spirit)."[20]

Simon Nicholls, editor of an Oxford University Press book on the composer, wrote " Indeed Skryabin was deeply interested by Mme Blavatsky’s ideas for the last ten years of his life. I have sat in the Skryabin Museum in Moscow and looked at one of the volumes of The Secret Doctrine in the French version, with Skryabin’s carefully ruled underlinings and pencilled comments, many of them."[21]

Theosophical influence in Prometheus symphony

Prometheus, "The Poem of Fire," Opus 60, was Scriabin's fifth and last symphony, written in 1909-1910. It was scored massively, with prominent piano and chorus, and was planned to be performed with a "color organ," which would project appropriate colors on a screen synchronized with the music.

Dr. James Cousins wrote an account of how this symphony written, that he heard while visiting the composer with his wife Margaret Cousins, in the suburbs of Brussels:

When Scriabine was a very young man, already noted as a composer and pianist, he went to Brussels, and there, among the younger group of artists in various mediums, he met Jean Delville. The two were attracted to one another. Scriabine noticed something in Delville that he himself lacked: Scriabine was groping towards some kind of comprehension of life. He asked Delville, in the same room where we heard the story, what was behind his attitude to life, and how he, the questioner, could reach a similar attitude. Delville produced two large volumes and put them before Scriabine. "Read these - and then set them to music," he said. Scriabine read the books - The Secret Doctrine. He went on fire with their revelation. The result was his immortal masterpiece, "Prometheus."... While Scriabine composed the Symphony, he came excitedly at intervals into Delville's drawing-room and played for the painter the musical ideas that were crowding in on him. At the same time Delville painted his wonderful picture of Prometheus falling from the sky with the gift of fire for the earth. He showed us the great canvas in his studio. It almost came to India. [i.e. to the Theosophical Society headquarters in Adyar.][22]

Scriabin's biographer added:

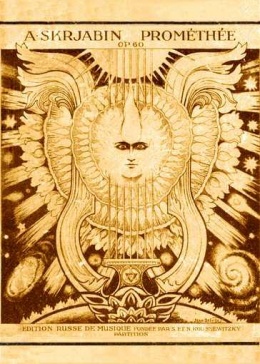

He [Scriabin] adored the cover design of his Prometheus symphony. It showed a sexless face surrounded by cosmic symbols, nebulae of clouds, spiraling comets, and was drawn by his Belgian friend, Jean Delville (b. 1867), a bachelor, professor of Fine Arts at the Royal Academy, and President of the national Federation of Artists and Sculptors. Looking at that cover of the androgyne or hermaphrodite, Scriabin said, "In those ancient races, male and female were one… the separation into poles hadn't yet taken place...[23]

Prometheus as a plot reeks of Theosophical symbolism and is Scriabin's only composition so heavily inflated with such paraphernalia. It exhales Brussels and the dense, mystical air of that city. Delville's cover design for the score shows a lyre ("the World," symbolized by music) rising from a lotus bloom ("the Womb," mind or Asia). In the center over the Star of David is Prometheus's face ("really the ancient symbol of Lucifer," Scriabin said, encompassing all religions). Delville, and perhaps Scriabin, had joined a secret cult within Theosophy called "Sons of the Flames of Wisdom." They worshiped Prometheus, because those fires, colors, lights were metasymbols of man's highest thoughts. Fire was Prometheus's stolen gift to man, and it lay deep within hearts...

To Scriabin, Prometheus had further symbolism beyond Theosophy's haziness. Lucifer was the "Light Bringer," according to the Christian Bible, and Satan was the "Disobedient Rebel." Sabaneeff's program notes... state that "Prometheus, Satanas, and Lucifer all meet in ancient myth. They represent the active energy of the universe, its creative principle. The fire is light, life, struggle, increase, abundance, and thought. At first, this powerful force manifests itself wearily, as languid thirsting for life. Within this lassitude then appears the primordial polarity between soul and matter. Later it does battle and conquers matter - of which it itself is a mere atom - and returns to the original quiet and tranquillity ... thus completing the cycle..."[24]

Musical compositions

Most of Scriabin's work was for piano in the usual forms - études, preludes, nocturnes, sonatas, mazurkas, etc. His orchestral works are fewer, but among the most popular.

Kurt Leland writes,

Among Scriabin’s mystically inclined works for orchestra are the Poem of Ecstasy, which depicts the union of male and female principles that continually recreates the universe...

Scriabin also composed ten piano sonatas, several of which have Theosophical subtexts. The Fourth Sonata is about flight toward a star, as in the experience of astral projection. The Seventh, subtitled White Mass, is about the mystical forces unleashed in a magical ceremony, and the Ninth (Black Mass) is about purging the corresponding dark forces. The Eighth Sonata uses five musical fragments to represent the constant interplay of the elements earth, water, air, fire, and, as he called it, “the mystical ether.”

Scriabin’s Tenth Sonata portrays solar insects “born from the sun,” “the sun’s kisses.” The radiant halo of trills with which the piece closes is one of the most effective depictions in music of the inner light associated with high meditative states, such as samadhi.[25]

For a complete list of the composer's works, see List of compositions by Alexander Scriabin. Here are some favorites:

Orchestral works

- Symphonic Poem in D minor. 1896.

- Piano Concerto in F-sharp minor, Op. 20. 1896.

- Symphony No. 1 in E major, Op. 26. 1900.

- Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 29. 1901.

- Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 43. The Divine Poem. 1904.

- The Poem of Ecstasy, Op. 54. Fourth Symphony. 1908.

- Prometheus: The Poem of Fire, Op. 60. Fifth Symphony. 1910.

Piano works

- Étude in C-sharp minor, No. 1 from Trois morceaux, Op. 2. 1887.

- 12 Études, Op. 8. 1894.

- 8 Études, Op. 42. 1903.

- Fantaisie in B minor, Op. 28. 1900. Sonata form.

- Impromptu à la Mazur in C major, No. 3 from Trois morceaux, Op. 2.

- Vers la flamme, Op. 72.

- 24 Preludes, Op. 11. 1896.

- Sonata-Fantaisie in G-sharp minor. 1886.

- Sonata No. 7 "White Mass", Op. 64.

Scriabin Museum

The Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum was established on July 17, 1922 to preserve the apartment where the composer lived for his final three years, in an old mansion on Arbat Street in Moscow. The composer's prized possessions were carefully restored, including his copy of The Secret Doctrine.[26] The museum preserves Scriabin's library, letters, sheet music, and other items.

Additional resources

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists articles about Scriabin.

- Alexander Scriabin Natal Horoscope at Khaldea.

- Blavatsky, Scriabin and Music at Blavatsky News 2.0

- Scriabin, Alexandre Nikolaevich to Theosophy World.

- Hull, A. Eaglefield. Scriabin. London: Kegan Paul, 1927.

- Sabbagh, Peter. The Development of Harmony in Scriabin's Works. 2003.

- Skryabin, Alexander. The Notebooks of Alexander Skryabin. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Translated by Simon Nicholls and Michael Pushkin, with annotations and comment by Simon Nicholls and foreword by Vladimir shkenazy.

- Swan, Alfred J. Scriabin. London: John Lane, 1923.

- Warner, Sybil Marguerite. "Scriabin: Musician and Theosophist" in Theosophy Forward. December 2, 2011. Edited and slightly expanded from Music and Listeners, by Sybil Marguerite Warner, with a foreword by C. Jinarajadasa (London: Service Magazine and Publications, 1911).

Notes

- ↑ Margaret Cousins, "Memorabilia of Scriabine - the Master Musician of Theosophy," The Theosophist 56 (November 1934), 173.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume I (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 109-112.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 109-112.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 141.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 150, 182-183.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 242.

- ↑ "Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in Russiapedia. Accessed October 23, 2016.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 258.

- ↑ "Prominent Russians: Aleksandr Scriabin" in Russiapedia. Accessed October 23, 2016.

- ↑ Simon Nicholls, "On the track of Scriabin as Pianist" at Scriabin Association website.

- ↑ Anthony Hewitt, "The Development of Dissonance in Scriabin's Piano Preludes" at Scriabin Association website.

- ↑ Gary Brown, "Music as Magic: Composer Alexander Scriabin" The American Theosophist 70.5 (May 1982), 157.

- ↑ Gary Lachman, "Concerto for Magic and Mysticism: Esotericism and Western Music." The Quest 90.4 (July-August, 2002), 132-137.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I,261, 272, 304.

- ↑ Cyril Scott, Music: Its Secret Influence Throughout the Ages (New York: Samuel Weiser Inc., 1958).

- ↑ Richard E. Overill, Alexander Scriabin’s Use of French Directions to the Pianist at Scriabin Association web page.

- ↑ Bowers(1969) Volume II, 52.

- ↑ Richard E. Overill, Alexander Scriabin’s Use of French Directions to the Pianist at Scriabin Association web page.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume II, 117.

- ↑ James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." The Theosophist47.3 (December 1925), 396.

- ↑ Simon Nicholls email to Leslie Price and Janet Kerschner. July 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Scriabine and Delville," The Theosophist 57.4 (January 1936), 358.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: a Biography, Second, Revised edition (New York: Dover, 1996), 71.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume II, 206-207.

- ↑ Kurt Leland, "Theosophical Music" Quest 99.2 (Spring, 2011): 61-64. Available at Quest website.

- ↑ Bowers (1969) Volume I, 87.