Henrietta Müller: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

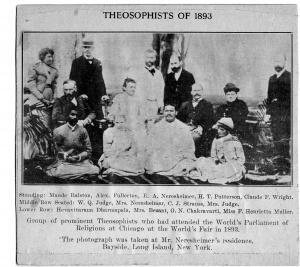

[[File:Theosophists of 1893.jpg|right|300px|thumb|Theosophists gathering after Parliament. Miss Müller seated at lower right]] | [[File:Theosophists of 1893.jpg|right|300px|thumb|Theosophists gathering after Parliament. Miss Müller seated at lower right]] | ||

'''Henrietta Müller''' or Mueller, a prominent women's rights activist, used her talents in the service of public reform. Best known for her radical opposition to taxation without representation, she became a popular speaker during her term as one of the first female members of the '''London School Board'''. She subsequently took up the pen to further women's cause through her journalism, which led her to found the first women's newspaper in England. <ref>Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21</ref> | |||

She was also a [[Theosophy|Theosophist]] who spoke at the [[World's Parliament of Religions (1893)|World's Parliament of Religions]] in Chicago, in 1893. She was among the [[Theosophical Society]] delegates who gathered at the home of [[August Neresheimer|E. A. Neresheimer]] in New York after the Parliament. | |||

==Early Years and Education == | ==Early Years and Education == | ||

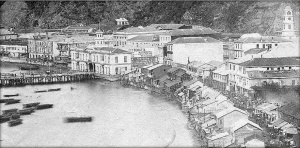

[[File: Bahía_de_Valparaíso_1863.jpg|left|300px|thumb|Bahia de Valparaiso, Chile in 1863]] | [[File: Bahía_de_Valparaíso_1863.jpg|left|300px|thumb|Bahia de Valparaiso, Chile in 1863]] | ||

Frances Henrietta Müller, later known as Henrietta Müller, was born in Valparaiso, Chile in 1846 and had a rich, diverse, and multicultural upbringing that exposed her to ideas and people from around the world. Henrietta’s mother was born in South America but of English descent and her father, William Müller, was from Gotha in central Germany. Both were incredibly influential in her life. She had a brother and two sisters. | |||

Henrietta’s mother was committed to the '''suffrage movement''' and Henrietta thought highly of her because she always encouraged a spirit of freedom in her daughters. Her father was a successful businessman in Chile and continued to do well after leaving to live and work in Britain in 1855. The children’s education was informal but nonetheless important. Henrietta enjoyed her thorough and wide-ranging education tremendously and also learned a lot when traveling with the family. In 1869, Girton College in Cambridge had become the first establishment to offer education for women to a degree level and there she studied Moral Sciences starting in 1873. However, the women’s degrees were not equal to men’s degrees and even Henrietta, who had free-minded parents, had to fight to go to college since society back then was afraid that studies could impair a woman’s primary duty to find a husband and raising a family and doctors believed that women’s desire for independence could lead to sickness and loss of fertility. She spent three happy years at Girton and those years were deeply formative in developing her interests in women’s suffrage. <ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.181 – 186</ref></br> | |||

==Activism and Journalism== | ==Activism and Journalism== | ||

[[File: The_Future_of_Single_Women.jpg|right|200px|thumb|Müller's first published article, 1884]] | |||

Henrietta was a passionate and prominent women’s rights activist and devoted her life to the advancement of women’s freedom of movement in all spheres. | |||

In 1876 she launched a women’s printing press with two others, hired 40 women and printed materials for women’s suffrage. She campaigned for education reform through the London School Board for 12 years beginning in 1879, against sexual violence towards women and girls, for equal pay for equal work, and even argued for contraception. She was also committed to campaigning for women’s rights to vote, for which she was arrested in 1884, and she refused to pay council tax on the ground that women were being taxed without representation.<ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.188 – 190</ref></br> | |||

<br>Henriette Müller published her first article, '''"The Future of Single Women,"''' anonymously in the ''Westminster Review'' in January 1884, but it was later printed and published in London by Ballantine, Hanson & Co. She dedicated this article to “all happy spinsters” and challenged the supposed superfluity of the unmarried woman.<ref>Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21</ref><ref>Müller, Henrietta. ''The Future of Single Women''. WikiSource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Future_of_Single_Women.pdf/2 Accessed on 7/20/21.</ref> She suggested that spinsters, possessing women's superior qualities of insight and self-control yet free from men's demands in marriage, should undertake the task of protecting the rights of women and children. <ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required </ref> | |||

<br>Henriette Müller published her first article, | |||

She wrote <blockquote> | She wrote <blockquote> | ||

The mental life of a single woman is free and untrammeled by any limits except such as are to her own advantage. Her difficulties in the way of development are only such as are common to all human beings. Her physical life is healthy and active, she retains her buoyancy and increases her nervous power if she knows how to take care of herself, and this lesson she is rapidly learning. The unmarried woman of today is a new, sturdy, and vigorous type. We find her neither the exalted ascetic nor the nerveless inactive creature of former days. She is intellectually trained and socially successful, her physique is as sound and vigorous as her mind. The world is before her in a freer, truer, and better sense than it is before any individual male or female. Her tastes are various and refined, her opportunities for cultivating them practically unlimited. Whether it be in the direction of society, or art, or travel, or philanthropy, or public duty, or a combination of many of these, there is nothing to let or hinder her from following her own will, there are no bonds, but such as bear no yoke, no restrictions but those of her own conscience and right principle. <ref>Müller, Henrietta. The Future of Single Women. WikiSource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Future_of_Single_Women.pdf/11 | The mental life of a single woman is free and untrammeled by any limits except such as are to her own advantage. Her difficulties in the way of development are only such as are common to all human beings. Her physical life is healthy and active, she retains her buoyancy and increases her nervous power if she knows how to take care of herself, and this lesson she is rapidly learning. The unmarried woman of today is a new, sturdy, and vigorous type. We find her neither the exalted ascetic nor the nerveless inactive creature of former days. She is intellectually trained and socially successful, her physique is as sound and vigorous as her mind. The world is before her in a freer, truer, and better sense than it is before any individual male or female. Her tastes are various and refined, her opportunities for cultivating them practically unlimited. Whether it be in the direction of society, or art, or travel, or philanthropy, or public duty, or a combination of many of these, there is nothing to let or hinder her from following her own will, there are no bonds, but such as bear no yoke, no restrictions but those of her own conscience and right principle. <ref>Müller, Henrietta. ''The Future of Single Women''. WikiSource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Future_of_Single_Women.pdf/11 | ||

Accessed on 8/20/21</ref></blockquote | Accessed on 8/20/21'</ref></blockquote> | ||

[[File: WomensJournals19thC.jpg|left| | [[File: WomensJournals19thC.jpg|left|200px|thumb|''The Women's Penny Paper'']] | ||

Henrietta founded and edited the weekly periodical '''''The Women’s Penny Paper''''' and later '''''The Women’s Herald''''' from 1888 until 1893, adopting the editorial pen-name Helena B. Temple, in which she wrote about things that were important or frustrating to her. <ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. ''Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear''. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.181 – 186</ref> The Women’s Penny Paper exhibited a lively and uncompromising feminism. It contained information and debates on a wide range of feminist campaigns, as well as biographical interviews with leading feminists.<ref>Brown, Heloise. Sharpe, Pamela. Summerfield, Penny. Abrams, Lynn. Beattie, Cordelia. ''The Truest Form of Patriotism: Pacifist Feminism in Britain, 1870-1902''. Manchester University Press, 2004, p. 27.</ref> It was the first British feminist periodical to adopt the interview as a regular feature and in an unsigned inaugural editorial, presumably written by Henrietta herself, the paper stated clearly that it would be "open to all shades of opinion, to the working woman as freely as to the educated lady; to the conservative and the radical, to the Englishwoman and foreigner."<ref> Van Remoortel, Marianne. "International Feminism, Domesticity, and the Interview in the Women's Penny Paper/Woman's Herald." ''Victorian Periodicals Review''. Baltimore Vol. 51, Iss. 2 (Summer 2018): 252-268.DOI:10.1353/vpr.2018.0013</ref></br> | |||

Henrietta founded and edited the weekly periodical The Women’s Penny Paper and later The Women’s Herald from 1888 until 1893, adopting the editorial pen-name Helena B. Temple, | |||

in which she wrote about things that were important or frustrating to her. | |||

<ref> Van Remoortel, Marianne. | |||

<br>Henrietta continued the nomadic life she was born into by travelling extensively as an adult, visiting nearly every country in Europe, as well as being a frequent visitor to India and America and regularly gave lectures about her travels and women’s rights. <ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.188 – 191</ref></br> | <br>Henrietta continued the nomadic life she was born into by travelling extensively as an adult, visiting nearly every country in Europe, as well as being a frequent visitor to India and America and regularly gave lectures about her travels and women’s rights. <ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.188 – 191</ref></br> | ||

| Line 39: | Line 31: | ||

==Theosophy== | ==Theosophy== | ||

<br>Throughout the 1880s Müller's heart was in the | <br>Throughout the 1880s Müller's heart was in the "woman's movement." Around 1890, however, she "gradually withdrew from civic efforts" and embarked upon a spiritual quest. She joined the [[Theosophical Society]] sometime between 1887 and 1891,<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''.</i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 184.</ref> drawn by its ideas of universal brotherhood and complementary male and female aspects to the spirit.<ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. "Müller, (Frances) Henrietta" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography''. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required. </ref></br> | ||

<br> She attended the Theosophical Convention in Adyar in December 1891 and some delegates suggested she visit a few branches in India and a lecturing tour was organized. She wrote about her first “tour” in India in | <br> She attended the Theosophical Convention in [[Adyar (campus)|Adyar]] [the Society's international headquarters in India] in December 1891 and some delegates suggested she visit a few branches in India and a lecturing tour was organized. She wrote about her first “tour” in India in [[The Theosophist (periodical)|''The Theosophist'']] and stated how pleased she was to get better acquainted with Indian people and how friendly they were.<ref> Müller, Henrietta. "A Lady’s Lecturing Tour in Southern India" ''The Theosophist'' Vol. 13, no. 06. http://iapsop.com/archive/materials/theosophist/theosophist_v13_n06_march_1892.pdf | ||

</ref></br> | </ref></br> | ||

<br> The original plan had been that she would accompany [[Annie Besant]], but Besant cancelled at the last minute, so Henrietta Müller went alone. Both Besant and Müller attended the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago in September 1893, where Müller addressed the Theosophical Congress, an event arranged as a prelude to the World’s Parliament of Religions. <ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required. </ref> In the first of the two papers that Henrietta Müller gave was | <br> The original plan had been that she would accompany [[Annie Besant]], but Besant cancelled at the last minute, so Henrietta Müller went alone. Both Besant and Müller attended the '''[[World's Parliament of Religions (1893)|World's Parliament of Religions]]''' in Chicago in September 1893, where Müller addressed the Theosophical Congress, an event arranged as a prelude to the World’s Parliament of Religions.<ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.</ref> In the first of the two papers that Henrietta Müller gave was "Theosophy as found in the Hebrew books and in the New Testament of Christians." and she declared herself to be a "Christian Woman and a Theosophist." <ref><i>The Theosophical Congress, </i> 1893:29 f.</ref> The Christianity of which she spoke, however, was the expression of a “Cosmic Intuition [that] reaches down to and is the voice of the Deity. It is One, Eternal, Undivided, Homogeneous.” <ref> <i>The Theosophical Congress, </i> 1893:31 f.</ref> On this basis, Müller directed attention not to differences but to the common, inner truths of all religions interpreted esoterically. <ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 185</ref> In der second paper “Theosophy and Women” she made plain her conviction that every religion or philosophical system should be judged in the light of whether it accords to women ‘a place of perfect equality with men.’ She recalled her own initial skepticism as to whether Theosophy did justice to women and the reassurance of [[Theosophical Society]] [[Founding of the Theosophical Society|Founder]] [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky|Madame Blavatsky]]’s reassurance that women enjoyed full equality with men in the Society and were not debarred from becoming 'a high adept.'<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 186.</ref></br> | ||

<br>Touring Ceylon and India in November 1893, this time with Besant, Müller's lectures drew crowds of Indian women, mostly in purdah, who had come to see 'the renowned woman-suffragist'. <ref> Nethercot, A.H. Last Four Lives of Annie Besant. 1963, page 17</ref>. For the first time, the Indian section of the Theosophical Society allowed Indian women to attend its convention, where Müller was also present. Many articles on Indian women appeared in the Women's Penny Paper before it ceased publication in 1893. <ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required. </ref></br> | <br>Touring Ceylon and India in November 1893, this time with Besant, Müller's lectures drew crowds of Indian women, mostly in purdah, who had come to see 'the renowned woman-suffragist'.<ref> Nethercot, A.H. ''Last Four Lives of Annie Besant''. 1963, page 17.</ref>. For the first time, the Indian section of the Theosophical Society allowed Indian women to attend its convention, where Müller was also present. Many articles on Indian women appeared in the ''Women's Penny Paper'' before it ceased publication in 1893.<ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.</ref></br> | ||

<br>In 1894, and thus barely a year before she parted from the Theosophical Society, Henrietta Müller edited a Theosophical publication entitled <i>The Yoga of Christ or the Science of the Soul</i>. The work is structured as an exchange of letters designed to present Jesus Christ as the fulfilment of the teachings of other | <br>In 1894, and thus barely a year before she parted from the Theosophical Society, Henrietta Müller edited a Theosophical publication entitled <i>The Yoga of Christ or the Science of the Soul</i>. The work is structured as an exchange of letters designed to present Jesus Christ as the fulfilment of the teachings of other 'yogis.'<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 186</ref></br> | ||

<br>In 1895 she returned from another visit to India where she had adopted a young Hindu man as her son. It was reported in | <br>In 1895 she returned from another visit to India where she had adopted a young Hindu man as her son. It was reported in [[The Path (periodical)|''The Path'']] in April 1895, that this adult son had added his mother’s name to his own and was known as Akshaya Kumar Ghosh Müller.<ref> Mirror of the Movement, India. The Path. 1895. Vol 10, April 1896, p. 31. https://theosophy.world/sites/default/files/Theosophical%20Publications/The%20Path/1895/path-10-1-1895-apr.pdf Accessed on 7/21/21.</ref> <ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.191 – 193</ref> Müller had taken the role of benefactor of Akshaya Kumar Gosh during her visit to India in late 1893 and with her support he took up a place at Cambridge with the hope that he would enter public life one day.<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 188.</ref></br> | ||

<br>In spite of her prominence in the organization, Henrietta | <br>In spite of her prominence in the organization, Henrietta Müller parted from the Theosophical Society in July 1895, announcing her decision in the <i>Madras Mail</i>. This parting took place after she had invited [[Vivekananda|Swami Vivekananda]] to come to Britain.<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 189.</ref></br> | ||

==The Ramakrishna Mission== | ==The Ramakrishna Mission== | ||

[[File: Ramakrishna_Mission.jpg|right|260px|thumb]] | [[File:Ramakrishna_Mission.jpg|right|260px|thumb|Ramakrishna Mission]] | ||

<br> | <br>Henrietta Müller met [[Vivekananda|Swami Vivekananda]] at the Parliament, and in 1895 invited him to London, where he stayed with [[ E. T. Sturdy]]. According to one source, the adopted son might have been the actual sender of the invitation, since he was a disciple of the Swami.<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''.</i>Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 188 and 190.</ref></br> | ||

<br>Swami Vivekananda made two extended trips to Britain in 1895 and 1896 and Henrietta Müller had expectations that Vivekananda could be put to service in causes to which she was already deeply committed and since she had considerable private means of her own, she supported his mission. Although Vivekananda had spoken enthusiastically of the independence of American women, he had yet to work out a role of women within his strategy for India’s material and spiritual regeneration.<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''.</i>Oxford University Press, 2000, p 190 ff.</ref></br> | |||

= | <br>In 1897, Swami Vivekananda’s ''From Colombo to Almora'', a book about a missionary journey, was published in London, with Henrietta Müller as the editor.<ref>Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present''. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/p''ublic/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 8/20/21</ref></br> | ||

<br> | <br>But some sort of tensions between him and Henrietta surfaced soon, and their break became public in 1898, because Henrietta Müller announced it in the press. Vivekananda wrote to a friend that "her defection was a great blow to me" and stated further that "she was such a great helper and worker" and that "she has plenty of the world’s goods and brains, but like myself – she now and then gets into violent nervous fits."<ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''.</i>Oxford University Press, 2000, p 191 -198 ff.</ref></br> | ||

==Last Years and Assessment== | |||

[[File: Washington_Post.png|left|260px|thumb|Lecture announcement, 1903]] | |||

She travelled one more time around the world in 1901, giving talks. One of these talks was advertised for women only and the invited guests included '''Susan B. Anthony'''. She also became an inventor and when she was 50 years old, she registered a cycle wear pattern she had designed; a three-piece interconnected costume.<ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.191 – 193.</ref> | |||

<br>She | <br>Henrietta Müller lived the last years in China and the USA. She lectured on "True and False Democracy" in Washington D.C. in 1903 which was reported in <i>The Washington Post</i>. <ref>Meeting of Press Women: | ||

Miss Henrietta Müller Lectured on “True and False Democracy. ''The Washington Post'', April 19, 1903.</ref> | |||

<br>She died of pneumonia on 4 January 1906 at her home in Washington D.C. She was 59 years old. She had also kept a London address in Westminster. Her sizable estate was left to her sister Eva.<ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. ''Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear''. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. P 193.</ref> | |||

<br>As both a writer and a speaker, Henrietta Müller delivered a pointed critique of masculine domination alongside a typically Victorian sexual essentialism. She also connected her feminist politics with spiritual ideals and edited books about Eastern religion. <ref>Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21</ref> | <br>As both a writer and a speaker, Henrietta Müller delivered a pointed critique of masculine domination alongside a typically Victorian sexual essentialism. She also connected her feminist politics with spiritual ideals and edited books about Eastern religion. <ref>Cambridge University Press, Orlando. ''Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present''. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21'</ref> | ||

<br>Henrietta Müller’s contributions to the feminine cause are significant. The hostile attitude to women’s desire for an education served to fuel Henrietta’s motivation to be an activist all her life and she believed it was instilled in her from birth: | <br>Henrietta Müller’s contributions to the feminine cause are significant. The hostile attitude to women’s desire for an education served to fuel Henrietta’s motivation to be an activist all her life and she believed it was instilled in her from birth: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote>I really cannot say how I came to feel as I do on the subject of the emancipation of women. I think it must have been born in me. During my girlhood I saw and felt a good deal of masculine tyranny. . . I made the deliberate choice to devote myself, body, soul, and spirit, to what was then the unpopular cause of women’s emancipation. I have never swerved a single instant from that position.<ref> Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. P 188</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | |||

<br>There are grounds for thinking that she may well have been a person of strongly and even aggressively held opinions. She attracted this kind of personal judgement most of her life. She was also known for personal celibacy and ascetic inclinations. <ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, p 198-199 </ref> As a feminist, Müller's writings reveal a characteristic mixture of Victorian sexual essentialism and hard-hitting analysis of male power. This approach brought Müller up against fierce opposition: she was even accused of being a | <br>There are grounds for thinking that she may well have been a person of strongly and even aggressively held opinions. She attracted this kind of personal judgement most of her life. She was also known for personal celibacy and ascetic inclinations. <ref>Beckerlegge, Gwilym. <i>The Ramakrishna Mission. ''The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement''. </i>Oxford University Press, 2000, p 198-199.</ref> As a feminist, Müller's writings reveal a characteristic mixture of Victorian sexual essentialism and hard-hitting analysis of male power. This approach brought Müller up against fierce opposition: she was even accused of being a "man-hater." Her campaigns, ideas, and subsequent withdrawal into spirituality have many parallels among later feminists, and her disappearance from historical record is typical for a woman whose life contained hard lessons for the men and women of her own and later generations.<ref> Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required. </ref> | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 96: | Line 84: | ||

[[Category:Lecturers|Müller, Henrietta]] | [[Category:Lecturers|Müller, Henrietta]] | ||

[[Category:Feminists|Müller, Henrietta]] | [[Category:Feminists|Müller, Henrietta]] | ||

[[Category:Suffragists|Müller, Henrietta]] | |||

[[Category:Social activists|Müller, Henrietta]] | [[Category:Social activists|Müller, Henrietta]] | ||

[[Category:Inventors|Müller, Henrietta]] | |||

[[Category:Imprisoned|Müller, Henrietta]] | |||

[[Category:Writers|Müller, Henrietta]] | [[Category:Writers|Müller, Henrietta]] | ||

[[Category:Editors|Müller, Henrietta]] | |||

[[Category:People|Müller, Henrietta]] | [[Category:People|Müller, Henrietta]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:52, 18 November 2021

Henrietta Müller or Mueller, a prominent women's rights activist, used her talents in the service of public reform. Best known for her radical opposition to taxation without representation, she became a popular speaker during her term as one of the first female members of the London School Board. She subsequently took up the pen to further women's cause through her journalism, which led her to found the first women's newspaper in England. [1]

She was also a Theosophist who spoke at the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago, in 1893. She was among the Theosophical Society delegates who gathered at the home of E. A. Neresheimer in New York after the Parliament.

Early Years and Education

Frances Henrietta Müller, later known as Henrietta Müller, was born in Valparaiso, Chile in 1846 and had a rich, diverse, and multicultural upbringing that exposed her to ideas and people from around the world. Henrietta’s mother was born in South America but of English descent and her father, William Müller, was from Gotha in central Germany. Both were incredibly influential in her life. She had a brother and two sisters.

Henrietta’s mother was committed to the suffrage movement and Henrietta thought highly of her because she always encouraged a spirit of freedom in her daughters. Her father was a successful businessman in Chile and continued to do well after leaving to live and work in Britain in 1855. The children’s education was informal but nonetheless important. Henrietta enjoyed her thorough and wide-ranging education tremendously and also learned a lot when traveling with the family. In 1869, Girton College in Cambridge had become the first establishment to offer education for women to a degree level and there she studied Moral Sciences starting in 1873. However, the women’s degrees were not equal to men’s degrees and even Henrietta, who had free-minded parents, had to fight to go to college since society back then was afraid that studies could impair a woman’s primary duty to find a husband and raising a family and doctors believed that women’s desire for independence could lead to sickness and loss of fertility. She spent three happy years at Girton and those years were deeply formative in developing her interests in women’s suffrage. [2]

Activism and Journalism

Henrietta was a passionate and prominent women’s rights activist and devoted her life to the advancement of women’s freedom of movement in all spheres.

In 1876 she launched a women’s printing press with two others, hired 40 women and printed materials for women’s suffrage. She campaigned for education reform through the London School Board for 12 years beginning in 1879, against sexual violence towards women and girls, for equal pay for equal work, and even argued for contraception. She was also committed to campaigning for women’s rights to vote, for which she was arrested in 1884, and she refused to pay council tax on the ground that women were being taxed without representation.[3]

Henriette Müller published her first article, "The Future of Single Women," anonymously in the Westminster Review in January 1884, but it was later printed and published in London by Ballantine, Hanson & Co. She dedicated this article to “all happy spinsters” and challenged the supposed superfluity of the unmarried woman.[4][5] She suggested that spinsters, possessing women's superior qualities of insight and self-control yet free from men's demands in marriage, should undertake the task of protecting the rights of women and children. [6]

She wrote

The mental life of a single woman is free and untrammeled by any limits except such as are to her own advantage. Her difficulties in the way of development are only such as are common to all human beings. Her physical life is healthy and active, she retains her buoyancy and increases her nervous power if she knows how to take care of herself, and this lesson she is rapidly learning. The unmarried woman of today is a new, sturdy, and vigorous type. We find her neither the exalted ascetic nor the nerveless inactive creature of former days. She is intellectually trained and socially successful, her physique is as sound and vigorous as her mind. The world is before her in a freer, truer, and better sense than it is before any individual male or female. Her tastes are various and refined, her opportunities for cultivating them practically unlimited. Whether it be in the direction of society, or art, or travel, or philanthropy, or public duty, or a combination of many of these, there is nothing to let or hinder her from following her own will, there are no bonds, but such as bear no yoke, no restrictions but those of her own conscience and right principle. [7]

Henrietta founded and edited the weekly periodical The Women’s Penny Paper and later The Women’s Herald from 1888 until 1893, adopting the editorial pen-name Helena B. Temple, in which she wrote about things that were important or frustrating to her. [8] The Women’s Penny Paper exhibited a lively and uncompromising feminism. It contained information and debates on a wide range of feminist campaigns, as well as biographical interviews with leading feminists.[9] It was the first British feminist periodical to adopt the interview as a regular feature and in an unsigned inaugural editorial, presumably written by Henrietta herself, the paper stated clearly that it would be "open to all shades of opinion, to the working woman as freely as to the educated lady; to the conservative and the radical, to the Englishwoman and foreigner."[10]

Henrietta continued the nomadic life she was born into by travelling extensively as an adult, visiting nearly every country in Europe, as well as being a frequent visitor to India and America and regularly gave lectures about her travels and women’s rights. [11]

Theosophy

Throughout the 1880s Müller's heart was in the "woman's movement." Around 1890, however, she "gradually withdrew from civic efforts" and embarked upon a spiritual quest. She joined the Theosophical Society sometime between 1887 and 1891,[12] drawn by its ideas of universal brotherhood and complementary male and female aspects to the spirit.[13]

She attended the Theosophical Convention in Adyar [the Society's international headquarters in India] in December 1891 and some delegates suggested she visit a few branches in India and a lecturing tour was organized. She wrote about her first “tour” in India in The Theosophist and stated how pleased she was to get better acquainted with Indian people and how friendly they were.[14]

The original plan had been that she would accompany Annie Besant, but Besant cancelled at the last minute, so Henrietta Müller went alone. Both Besant and Müller attended the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago in September 1893, where Müller addressed the Theosophical Congress, an event arranged as a prelude to the World’s Parliament of Religions.[15] In the first of the two papers that Henrietta Müller gave was "Theosophy as found in the Hebrew books and in the New Testament of Christians." and she declared herself to be a "Christian Woman and a Theosophist." [16] The Christianity of which she spoke, however, was the expression of a “Cosmic Intuition [that] reaches down to and is the voice of the Deity. It is One, Eternal, Undivided, Homogeneous.” [17] On this basis, Müller directed attention not to differences but to the common, inner truths of all religions interpreted esoterically. [18] In der second paper “Theosophy and Women” she made plain her conviction that every religion or philosophical system should be judged in the light of whether it accords to women ‘a place of perfect equality with men.’ She recalled her own initial skepticism as to whether Theosophy did justice to women and the reassurance of Theosophical Society Founder Madame Blavatsky’s reassurance that women enjoyed full equality with men in the Society and were not debarred from becoming 'a high adept.'[19]

Touring Ceylon and India in November 1893, this time with Besant, Müller's lectures drew crowds of Indian women, mostly in purdah, who had come to see 'the renowned woman-suffragist'.[20]. For the first time, the Indian section of the Theosophical Society allowed Indian women to attend its convention, where Müller was also present. Many articles on Indian women appeared in the Women's Penny Paper before it ceased publication in 1893.[21]

In 1894, and thus barely a year before she parted from the Theosophical Society, Henrietta Müller edited a Theosophical publication entitled The Yoga of Christ or the Science of the Soul. The work is structured as an exchange of letters designed to present Jesus Christ as the fulfilment of the teachings of other 'yogis.'[22]

In 1895 she returned from another visit to India where she had adopted a young Hindu man as her son. It was reported in The Path in April 1895, that this adult son had added his mother’s name to his own and was known as Akshaya Kumar Ghosh Müller.[23] [24] Müller had taken the role of benefactor of Akshaya Kumar Gosh during her visit to India in late 1893 and with her support he took up a place at Cambridge with the hope that he would enter public life one day.[25]

In spite of her prominence in the organization, Henrietta Müller parted from the Theosophical Society in July 1895, announcing her decision in the Madras Mail. This parting took place after she had invited Swami Vivekananda to come to Britain.[26]

The Ramakrishna Mission

Henrietta Müller met Swami Vivekananda at the Parliament, and in 1895 invited him to London, where he stayed with E. T. Sturdy. According to one source, the adopted son might have been the actual sender of the invitation, since he was a disciple of the Swami.[27]

Swami Vivekananda made two extended trips to Britain in 1895 and 1896 and Henrietta Müller had expectations that Vivekananda could be put to service in causes to which she was already deeply committed and since she had considerable private means of her own, she supported his mission. Although Vivekananda had spoken enthusiastically of the independence of American women, he had yet to work out a role of women within his strategy for India’s material and spiritual regeneration.[28]

In 1897, Swami Vivekananda’s From Colombo to Almora, a book about a missionary journey, was published in London, with Henrietta Müller as the editor.[29]

But some sort of tensions between him and Henrietta surfaced soon, and their break became public in 1898, because Henrietta Müller announced it in the press. Vivekananda wrote to a friend that "her defection was a great blow to me" and stated further that "she was such a great helper and worker" and that "she has plenty of the world’s goods and brains, but like myself – she now and then gets into violent nervous fits."[30]

Last Years and Assessment

She travelled one more time around the world in 1901, giving talks. One of these talks was advertised for women only and the invited guests included Susan B. Anthony. She also became an inventor and when she was 50 years old, she registered a cycle wear pattern she had designed; a three-piece interconnected costume.[31]

Henrietta Müller lived the last years in China and the USA. She lectured on "True and False Democracy" in Washington D.C. in 1903 which was reported in The Washington Post. [32]

She died of pneumonia on 4 January 1906 at her home in Washington D.C. She was 59 years old. She had also kept a London address in Westminster. Her sizable estate was left to her sister Eva.[33]

As both a writer and a speaker, Henrietta Müller delivered a pointed critique of masculine domination alongside a typically Victorian sexual essentialism. She also connected her feminist politics with spiritual ideals and edited books about Eastern religion. [34]

Henrietta Müller’s contributions to the feminine cause are significant. The hostile attitude to women’s desire for an education served to fuel Henrietta’s motivation to be an activist all her life and she believed it was instilled in her from birth:

I really cannot say how I came to feel as I do on the subject of the emancipation of women. I think it must have been born in me. During my girlhood I saw and felt a good deal of masculine tyranny. . . I made the deliberate choice to devote myself, body, soul, and spirit, to what was then the unpopular cause of women’s emancipation. I have never swerved a single instant from that position.[35]

There are grounds for thinking that she may well have been a person of strongly and even aggressively held opinions. She attracted this kind of personal judgement most of her life. She was also known for personal celibacy and ascetic inclinations. [36] As a feminist, Müller's writings reveal a characteristic mixture of Victorian sexual essentialism and hard-hitting analysis of male power. This approach brought Müller up against fierce opposition: she was even accused of being a "man-hater." Her campaigns, ideas, and subsequent withdrawal into spirituality have many parallels among later feminists, and her disappearance from historical record is typical for a woman whose life contained hard lessons for the men and women of her own and later generations.[37]

Notes

- ↑ Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.181 – 186

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.188 – 190

- ↑ Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21

- ↑ Müller, Henrietta. The Future of Single Women. WikiSource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Future_of_Single_Women.pdf/2 Accessed on 7/20/21.

- ↑ Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required

- ↑ Müller, Henrietta. The Future of Single Women. WikiSource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Future_of_Single_Women.pdf/11 Accessed on 8/20/21'

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.181 – 186

- ↑ Brown, Heloise. Sharpe, Pamela. Summerfield, Penny. Abrams, Lynn. Beattie, Cordelia. The Truest Form of Patriotism: Pacifist Feminism in Britain, 1870-1902. Manchester University Press, 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ Van Remoortel, Marianne. "International Feminism, Domesticity, and the Interview in the Women's Penny Paper/Woman's Herald." Victorian Periodicals Review. Baltimore Vol. 51, Iss. 2 (Summer 2018): 252-268.DOI:10.1353/vpr.2018.0013

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.188 – 191

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement.Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 184.

- ↑ Auchmuty, Rosemary. "Müller, (Frances) Henrietta" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.

- ↑ Müller, Henrietta. "A Lady’s Lecturing Tour in Southern India" The Theosophist Vol. 13, no. 06. http://iapsop.com/archive/materials/theosophist/theosophist_v13_n06_march_1892.pdf

- ↑ Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.

- ↑ The Theosophical Congress, 1893:29 f.

- ↑ The Theosophical Congress, 1893:31 f.

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 185

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 186.

- ↑ Nethercot, A.H. Last Four Lives of Annie Besant. 1963, page 17.

- ↑ Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 186

- ↑ Mirror of the Movement, India. The Path. 1895. Vol 10, April 1896, p. 31. https://theosophy.world/sites/default/files/Theosophical%20Publications/The%20Path/1895/path-10-1-1895-apr.pdf Accessed on 7/21/21.

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.191 – 193

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 188.

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 189.

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement.Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 188 and 190.

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement.Oxford University Press, 2000, p 190 ff.

- ↑ Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 8/20/21

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement.Oxford University Press, 2000, p 191 -198 ff.

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. Pp.191 – 193.

- ↑ Meeting of Press Women: Miss Henrietta Müller Lectured on “True and False Democracy. The Washington Post, April 19, 1903.

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. P 193.

- ↑ Cambridge University Press, Orlando. Women’s Writings in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the present. Henrietta Müller, Overview Page. http://orlando.cambridge.org/public/svPeople?person_id=mullhe. Accessed on 7/20/21'

- ↑ Jungnickel, Kat. Bikes and Bloomers. Victorian Women Inventors and Their Extraordinary Cycle Wear. Goldsmiths, University London. 2020. P 188

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym. The Ramakrishna Mission. The Making of a Modern Hindu Movement. Oxford University Press, 2000, p 198-199.

- ↑ Auchmuty, Rosemary. Müller, (Frances) Henrietta. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'. https://www-oxforddnb-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-56279 - Subscription required.