Joséphin Péladan

Joséphin Péladan (* March 28, 1858 in Lyon, France; † June 27, 1918 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France) was a French author, critic and occultist who had a vision for societal reform through art. He established the Salon de la Rose+Croix for painters, writers, and musicians sharing his artistic ideals, the Symbolists in particular. Although Péladan did not subscribe to Theosophical teachings, from a broader historical perspective these two currents met in the work of Symbolist artists, and the artists belonging to the Salon d'Art Idéalist founded by Jean Delville.[1]

Youth

Péladan was born into a Lyon family that was Roman Catholic; his father was a journalist who had written on prophecies, and professed a philosophic-occult Catholicism. He studied at Jesuit colleges at Avignon and Nîmes. After he failed his baccalaureate, he moved to Paris and became a literary and art critic. His older brother Adrien studied alchemy and occultism as well.

By the age of 26 he had formulated a complex, coherent cosmology of his own, based in part on world mythology, which he had studied from a young age, and deeply influenced by a tradition of pansophy (a way of combining all human knowledge according to analogical principles, and viewing human history through a form of allegorical hermeneutics, whereby events are interpreted as part of a larger narrative in which events within the human microcosm reflect the celestial macrocosm, and can be revealed through myths, legends, and their correspondences) and “philosophical” history that was eclipsed during the Enlightenment, but which remained a significant element in esoteric thought; a complex of cultural currents that enjoyed a significant revival in the second half of the nineteenth century. [2]

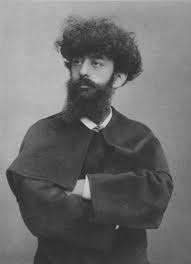

In 1884 Péladan imposed himself on the Parisian public by publishing Le Vice Supreme, a fantastic mystic-erotic novel in which poetry alternates with a no less studied prose: “Faithful to your monstrous vice, O daughter of da Vinci, corrupting Muse of the aesthetics of evil, your smile may fade from the canvas, but it is engraved forever in my heart.” Péladan, who changed his name from Joseph to Joséphin, described himself as ‘the sandwich-man of the Beyond,’ exhumed a mystical society founded in Germany in the late Middle Ages (Rosicrucianism), declared himself its leader, and crowned himself Sâr Merodac, a title which enabled him to dress himself up in a costume reminiscent of Lohengrin and Nebuchadnezzar. He was a dark, handsome man, with bushy hair and a bushy beard. Péladan obtained fame, drawing on two sources from which all those who were disgusted with materialism would drink: occultism and aestheticism. His books came out in rapid succession, under the general title La Decadence Latine. [3]

Portraits of Joséphin Péladan

The first portrait on the left of Sâr Merodack Joséphin Péladan by Marcellin Desboutin exemplifies the subject’s distinctive dandyish attitute. Striking a cocky pose and set against a richly decorated background, Péladan looks confidently at the viewer. His black tailored vestments, white ruffled collar, gloves, and cane assert an aristocratic air and speak to his preoccupation with the cult of his persona. [4]

On the right we see the portrait by Alexander Seon, one of the most dedicated supporters of the Salon de la Rose+Croix (R+C), where he exhibited more works than any other artist. Among the R+C artists he was a more stringent follower of Joséphin Péladan’s esoteric ideals, including his belief in the mystically transformative power of art and beauty. The two men's close rapport is apparent in this portrait, in which Péladan is in a priest-like guise with violet robes and his visage in sharp profile as he looks nobly towards the heavens. Across the top of the painting, incised in the back-ground, appears SAR JOSEPHIN PELADAN. The title Sâr ("leader" in Assyrian) reiterates Péladan’s self-appointed role as grande maitre of the R+C. Péladan praised the portrait - not least of all because it represented him in his chosen state of remove from modern life, and as spiritual leader. [5]

Jean Delville’s grandiose portrait of Joséphin Péladan presents him in a full-length Byzantinesque composition replete with iconography also referencing his self-appointed role as Sâr of his Rosicrucian order. Christ-like, Péladan stands in a frontal pose, eyes turned toward God, his right hand raised in blessing, with the index finger gesturing upward. The pointed arch framing the Sâr's head is flanked on both sides by Lamassu, the Assyrian winged deity that is part human, part lion and that is a motif in R+C catalogues and elsewhere. Featuring a rose and flaming cross, the R+C's emblem interlocks in a repeating, all-over pattern that fills and visually flattens the background, as well as bedecks the frame. The religiosity of the portrait is emphasized by the incense burner at Péladan's feet. [6]

Salon de la Rose+Croix

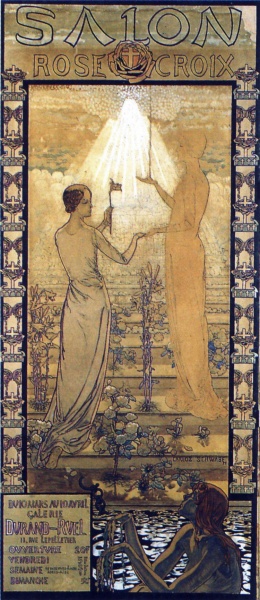

In 1892 Joséphin Péladan organized the first Salon de la Rose+Croix to represent the doctrines of the Rosicrucian order – a fraternal, esoteric religious group. Short-lived, the Salon was held from 1892 until 1897 at various gallery spaces around Paris and convened Symbolist artists from Europe and the United States. Péladan preferred an enigmatic and mystical strain of Symbolism, a literary and artistic movement that was widespread by the 1890s. Symbolism rejected the secular outlook, scientific theories, and Realist aesthetics that had taken hold in the nineteenth century in favor of the spiritual, imaginary, and stylized. R+C artists embraced these principles and aimed to prevail over the base materiality of the physical world in a quest for the ideal.

In this poster on the left by Carlos Schwabe for the first R+C Salon, two female figures ascend a staircase toward a celestial dimension. The lily and the smoking heart they hold symbolize purity and faith, respectively. The third woman is left behind, chained in the base of muck materiality.

Participating artists varied in ideology and, to some extent, in style, but primarily employed a version of Symbolism visually characterized by sinuous lines, elongated bodies, and flattened forms. Their subject matter was allegorical, literary, mythical, or religious, replete with arcane symbols, ethereal women, androgynous beings, and monstrous creatures. They gravitated to theses such as the Greek mythological poet Orpheus, the art and precepts of the early Italian Renaissance, New Testament narratives, and female stereotypes.

For example, the Belgian Jean Delville, whose portrait of Joséphin Péladan is shown above, and who was the first General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in Belgium, from 1911-1913, was among the participating artists that fervently shared Joséphin Péladan’s beliefs in the spiritual power of art, exhibited in the first four salons, earning particular admiration in 1894 for The Death of Orpheus (see below). As mentioned above, during the nineteenth century, Orpheus, the supernaturally talented poet of classical Western mythology, was a popular paradigm for the artist as enchanter, seer, and martyr whose creations transcend death. [7]

Personality cults developed around certain individuals, notably Péladan himself and the German opera composer Richard Wagner, whose concept of Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art combining multiple mediums – inspired interdisciplinary activities at the Salon, including musical performance, theatrical productions, and lectures. [8]

Péladan and the R+C circle repudiated the empirical bedrock of Naturalism and, by extension, Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, as well as their subjects from everyday life. Painters and sculptors who showed at the Salon de la R+C sought to convey the “ideal”, a term popularized by the Symbolist theorist Albert Aurier in reference to elevated thought. [9]

Legacy

Péladan left a spectacular legacy of 100 books, several thousand articles, and was responsible for inspiring a generation of artists and authors as far afield as Russia and South America. Today his works are all but forgotten, encountered only within treatises on the Decadent movement or in brief references in academic studies of fin-de-siècle French Occultism, and the majority of these references tend to perpetuate the sense of his eccentricity and peculiarity. According to the biographer Robert Pincus-Witten, there is no other literary figure more ridiculed and caricatured than Joséphin Péladan [10] and he seems to have been an attention-seeking and arrogant braggart. All of Péladan’s actions in the public sphere had the goal to show the world that art is man’s effort to realize the Ideal, to form and represent the supreme idea. To make the Invisible Visible was his vision of ensouled art. [11][12]

While Péladan and the Salon are not very known today, they garnered attention during the 1890s. These R+C exhibitions were an international crossroads for artists seeking to underscore the spiritual dimension of art and provoke visionary states of mind in their viewers. These transcendent aspirations were carried on in the early twentieth century by the pioneers of abstract painting such as Vasili Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, who were weaned on Symbolism and owed their theories, in varying degrees, to Theosophy. [13]

The Guggenheim Museum in New York City featured in the exhibition Mystical Symbolism from June 3rd until October 4th, 2017 works that were shown in Péladan’s Salons and evoked the unique atmosphere that he fostered. [14]

Notes

- ↑ Who was Josephin Pealdin? http://peladan.net/symbolist-art/who-was-josephin-peladan-3/. Web 9 August, 217

- ↑ Chaitow, S. Making the Invisible Visible: Péladan’s vision of Ensouled Art. 6 August, 2015. http://www.projectawe.org/blog/2015/8/4/making-the-invisible-visible-pladans-vision-of-ensouled-art. Web. 9 August, 2017

- ↑ The Writers No-One reads. http://writersnoonereads.tumblr.com/post/83435190502/peladan. Web. 8 August 2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Green, Vivian. Mystical Symbolism, The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris 1892-1897. Published on the occasion of the exhibition Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de da Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892-1897. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Print, 2017

- ↑ Pincus-Witten, Robert. Occult Symbolism in France. Print. New York: Garland, 1976. p.2

- ↑ Who was Josephin Péladan? http://peladan.net/symbolist-art/who-was-josephin-peladan-3/. Web 9 August, 217

- ↑ Chaitow, S. Making the Invisible Visible: Peladan’s vision of Ensouled Art. 6 August, 2015. http://www.projectawe.org/blog/2015/8/4/making-the-invisible-visible-pladans-vision-of-ensouled-art. Web. 9 August, 2017

- ↑ Greene, Vivian. Senior Curator, Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Art. From: Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. New York, 6/3 - 10/4/2017

- ↑ Guggenheim Presents Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rois+Croix. https://www.guggenheim.org/press-release/mystical-symbolism-salon-rose-croix-paris. Web. 8 August, 2017