Bede Griffiths: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Christian clergy|Griffiths, Bede]] | [[Category:Christian clergy|Griffiths, Bede]] | ||

[[Category:Mystics|Griffiths, Bede]] | |||

[[Category:Nationality British|Griffiths, Bede]] | [[Category:Nationality British|Griffiths, Bede]] | ||

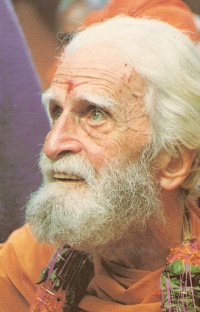

[[File:Bede Griffiths.jpg|200px|right]] | [[File:Bede Griffiths.jpg|200px|right]] | ||

Father Bede Griffiths (December 17, 1906 – May 13, 1993) was one of the greatest mystics and thinkers of the twentieth-century. An English Benedictine monk, he lived in lived and worked in [[ashram]]s of South India for the last 37 years of his life. He became a noted [[Yoga|yogi]] known as Swami Dayananda ("bliss of compassion") and led the development of dialogue between [[Christianity]] and [[Hinduism]] as part of the Christian Ashram Movement. His spiritual understanding transcended all religious dogma. | Father Bede Griffiths (December 17, 1906 – May 13, 1993) was one of the greatest mystics and thinkers of the twentieth-century. An English Benedictine monk, he lived in lived and worked in [[ashram]]s of South India for the last 37 years of his life. He became a noted [[Yoga|yogi]] known as Swami Dayananda ("bliss of compassion") and led the development of dialogue between [[Christianity]] and [[Hinduism]] as part of the Christian Ashram Movement. His belief in the brotherhood of all mankind and his attempt to bridge religious differences with interfaith dialogue makes his writings appealing to Theosophists. His spiritual understanding transcended all religious dogma. | ||

. | |||

== Early life and education == | == Early life and education == | ||

| Line 11: | Line 13: | ||

== Benedictine monastic life == | == Benedictine monastic life == | ||

Griffiths was received by the abbey as a postulant a month after his reception into the Catholic Church. On 29 | Griffiths was received by the abbey as a postulant a month after his reception into the Catholic Church. On December 29, 1932, he entered the novitiate and was given the monastic name of "Bede". He made his profession in 1937 and was ordained to the Catholic priesthood in 1940. | ||

After a number of years of monastic life in England and Scotland, Griffiths met Father Benedict Alapatt, a European-born monk of Indian ancestry who wanted to establish a monastery in India. Griffiths had already been introduced to Eastern thought, yoga and the Vedas and took interest in this proposed project. In 1955, he and Father Alapatt went to India, attempting to establish a monastery near Bangalore. In 1958 Griffiths left the location, saying that he found it "too Western".<ref>Pascaline Coff OSB, "Man, Monk, Mystic," The Bede Griffiths Trust, at [http://www.bedegriffiths.com/bede-griffiths]</ref> | After a number of years of monastic life in England and Scotland, Griffiths met Father Benedict Alapatt, a European-born monk of Indian ancestry who wanted to establish a monastery in India. Griffiths had already been introduced to Eastern thought, yoga and the Vedas and took interest in this proposed project. In 1955, he and Father Alapatt went to India, attempting to establish a monastery near Bangalore. In 1958 Griffiths left the location, saying that he found it "too Western".<ref>Pascaline Coff OSB, "Man, Monk, Mystic," The Bede Griffiths Trust, at [http://www.bedegriffiths.com/bede-griffiths]</ref> | ||

Griffiths then joined with a Belgian monk, Father Francis Acharya, to establish Kristiya Sanyasa Samaj, Kurisumala Ashram (Mountain of the Cross), a Syriac Rite monastery of the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church in Kerala. They sought to develop a form of monastic life based in the Indian tradition, adopting the saffron garments of the Indian [[Sannyasa|sannyasin]]. At that point, Father Griffiths took the Sanskrit name "Dayananda" ("bliss of compassion"). During that time he continued his studies in the religions and cultures of India, writing ''Christ in India''. He also visited the United States | Griffiths then joined with a Belgian monk, Father Francis Acharya, to establish Kristiya Sanyasa Samaj, Kurisumala Ashram (Mountain of the Cross), a Syriac Rite monastery of the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church in Kerala. They sought to develop a form of monastic life based in the Indian tradition, adopting the saffron garments of the Indian [[Sannyasa|sannyasin]]. At that point, Father Griffiths took the Sanskrit name "Dayananda" ("bliss of compassion"). During that time he continued his studies in the religions and cultures of India, writing ''Christ in India''. He also visited the United States, giving a number of talks about East-West dialogue, and was interviewed by CBS television. | ||

Later, in 1968, he moved to Shantivanam ("Forest of Peace") ashram in Tamil Nadu, which had been founded in 1950 by French Benedictine monks who had developed a religious lifestyle | Later, in 1968, he moved to Shantivanam ("Forest of Peace") ashram in Tamil Nadu, which had been founded in 1950 by French Benedictine monks who had developed a religious lifestyle in authentic Indian fashion, using English, Sanskrit and Tamil in their religious services. They had built the ashram buildings by hand, in the style of the poor of the country. Griffiths came with two other monks to take up life there when the founding monks retired. | ||

Griffiths resumed | Griffiths resumed study of Indian thought, trying to relate it to Christian theology. He wrote twelve books on Hindu-Christian dialogue. During this period, Griffiths desired to reconnect himself with the Benedictine Order and sought a monastic congregation which would accept him in the way of life he had developed over the decades. He was welcomed by the Camaldolese monks, and he and his ashram joined the Camaldolese Congregation of the Order of Saint Benedict (O.S.B. Cam.). | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

"Going native" created tensions with the Catholic hierarchy as did Bede Griffiths' remarkably progressive views. These included believing that homosexual love was "as normal and natural as love between people of the opposite sex". He advocated inter-faith communities and wanted a Church that was more concerned with love than sin. He realised that God was feminine as well as masculine and was one of the first advocates of married clergy and ministries for women. Like that other great Catholic mystic Thomas Merton who also travelled to the East, Griffiths believed that meditation should take a central place in worship.<ref>"This man is dangerous", An Overgrown Path website, July 30, 2008 at [http://www.overgrownpath.com/2008/07/this-man-is-dangerous.html]</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Griffiths was a proponent of integral thought, which attempts to harmonise scientific and spiritual world views. In a 1983 interview with Theosophist [[Renée Weber]], he stated, "We're now being challenged to create a theology which would use the findings of modern science and eastern mysticism which, as you know, coincide so much, and to evolve from that a new theology which would be much more adequate."<ref>Renée Weber, ''Dialogues With Scientists and Sages: The Search for Unity'' (London and New York, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 163 ISBN 0-7102-0655-0</ref> | Father Griffiths was a proponent of integral thought, which attempts to harmonise scientific and spiritual world views. In a 1983 interview with Theosophist [[Renée Weber]], he stated, "We're now being challenged to create a theology which would use the findings of modern science and eastern mysticism which, as you know, coincide so much, and to evolve from that a new theology which would be much more adequate."<ref>Renée Weber, ''Dialogues With Scientists and Sages: The Search for Unity'' (London and New York, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 163 ISBN 0-7102-0655-0</ref> | ||

== Connection with the Theosophical Society == | == Connection with the Theosophical Society == | ||

Bede Griffiths | Bede Griffiths visited the [[Theosophical Society in America]] in 1983. In a public program, Father Griffiths discussed the importance of the ecumenical movement and how the great world religions can complement one another. Theologian Kenneth Vaux spoke about the need for a spiritual transformation in the individual as a basis for changing secular society. Dora Kunz, past president of the Theosophical Society in America, acted as moderator for the discussion which followed.<ref>Bede Griffiths and Kenneth Vaux, "Interface Between Christianity and Other Faiths," (Wheaton:Theosophical Publishing House, 1983). CD. Quest Books Web page [http://www.questbooks.net/title.cfm?bookid=630]</ref> | ||

Dora Kunz | Dora Kunz also conducted an interview with Father Griffiths during that visit. He told her how as a young man he first became interested in Eastern religions and philosophies. He discussed the differences between prayer, meditation, and contemplation from both the Christian and Indian points of view. He maintained that a devout seeker can experience the One Reality, but in different ways according to their respective traditions. Learning about other faiths can help enrich our understanding of our own faith, in his view, but we cannot hope to find or experience the underlying Unity at a doctrinal or theological level. We can only approach that divine Mystery within by leaving behind all religious dogma and experiencing that divine Reality within the sanctuary of our own hearts.<ref>"Interview with Father Bede Griffiths," (Wheaton:Theosophical Publishing House, 1983). DVD. Quest Books Web page [http://www.questbooks.net/title.cfm?bookid=1875]</ref> | ||

== Impact == | == Impact == | ||

| Line 60: | Line 62: | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 04:34, 25 April 2012

Father Bede Griffiths (December 17, 1906 – May 13, 1993) was one of the greatest mystics and thinkers of the twentieth-century. An English Benedictine monk, he lived in lived and worked in ashrams of South India for the last 37 years of his life. He became a noted yogi known as Swami Dayananda ("bliss of compassion") and led the development of dialogue between Christianity and Hinduism as part of the Christian Ashram Movement. His belief in the brotherhood of all mankind and his attempt to bridge religious differences with interfaith dialogue makes his writings appealing to Theosophists. His spiritual understanding transcended all religious dogma. .

Early life and education

Griffiths was born Alan Richard Griffiths, the youngest of three children of a middle class family that fell into hard times. An excellent student, he earned a scholarship to the University of Oxford where, in 1925, he began his studies in English literature and philosophy at Magdalen College. In his third year at university he came under the tutelage of the professor and Christian apologist C. S. Lewis who became a lifelong friend. Griffiths graduated from Oxford in 1929 with a degree in journalism. After a crisis in faith and a spiritual breakthrough, he left the Church of England in which he had been raised. After a stay at the Benedictine monastery of Prinknash Abbey in November 1931, he was received into the Roman Catholic Church.

Benedictine monastic life

Griffiths was received by the abbey as a postulant a month after his reception into the Catholic Church. On December 29, 1932, he entered the novitiate and was given the monastic name of "Bede". He made his profession in 1937 and was ordained to the Catholic priesthood in 1940.

After a number of years of monastic life in England and Scotland, Griffiths met Father Benedict Alapatt, a European-born monk of Indian ancestry who wanted to establish a monastery in India. Griffiths had already been introduced to Eastern thought, yoga and the Vedas and took interest in this proposed project. In 1955, he and Father Alapatt went to India, attempting to establish a monastery near Bangalore. In 1958 Griffiths left the location, saying that he found it "too Western".[1]

Griffiths then joined with a Belgian monk, Father Francis Acharya, to establish Kristiya Sanyasa Samaj, Kurisumala Ashram (Mountain of the Cross), a Syriac Rite monastery of the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church in Kerala. They sought to develop a form of monastic life based in the Indian tradition, adopting the saffron garments of the Indian sannyasin. At that point, Father Griffiths took the Sanskrit name "Dayananda" ("bliss of compassion"). During that time he continued his studies in the religions and cultures of India, writing Christ in India. He also visited the United States, giving a number of talks about East-West dialogue, and was interviewed by CBS television.

Later, in 1968, he moved to Shantivanam ("Forest of Peace") ashram in Tamil Nadu, which had been founded in 1950 by French Benedictine monks who had developed a religious lifestyle in authentic Indian fashion, using English, Sanskrit and Tamil in their religious services. They had built the ashram buildings by hand, in the style of the poor of the country. Griffiths came with two other monks to take up life there when the founding monks retired.

Griffiths resumed study of Indian thought, trying to relate it to Christian theology. He wrote twelve books on Hindu-Christian dialogue. During this period, Griffiths desired to reconnect himself with the Benedictine Order and sought a monastic congregation which would accept him in the way of life he had developed over the decades. He was welcomed by the Camaldolese monks, and he and his ashram joined the Camaldolese Congregation of the Order of Saint Benedict (O.S.B. Cam.).

"Going native" created tensions with the Catholic hierarchy as did Bede Griffiths' remarkably progressive views. These included believing that homosexual love was "as normal and natural as love between people of the opposite sex". He advocated inter-faith communities and wanted a Church that was more concerned with love than sin. He realised that God was feminine as well as masculine and was one of the first advocates of married clergy and ministries for women. Like that other great Catholic mystic Thomas Merton who also travelled to the East, Griffiths believed that meditation should take a central place in worship.[2]

Father Griffiths was a proponent of integral thought, which attempts to harmonise scientific and spiritual world views. In a 1983 interview with Theosophist Renée Weber, he stated, "We're now being challenged to create a theology which would use the findings of modern science and eastern mysticism which, as you know, coincide so much, and to evolve from that a new theology which would be much more adequate."[3]

Connection with the Theosophical Society

Bede Griffiths visited the Theosophical Society in America in 1983. In a public program, Father Griffiths discussed the importance of the ecumenical movement and how the great world religions can complement one another. Theologian Kenneth Vaux spoke about the need for a spiritual transformation in the individual as a basis for changing secular society. Dora Kunz, past president of the Theosophical Society in America, acted as moderator for the discussion which followed.[4]

Dora Kunz also conducted an interview with Father Griffiths during that visit. He told her how as a young man he first became interested in Eastern religions and philosophies. He discussed the differences between prayer, meditation, and contemplation from both the Christian and Indian points of view. He maintained that a devout seeker can experience the One Reality, but in different ways according to their respective traditions. Learning about other faiths can help enrich our understanding of our own faith, in his view, but we cannot hope to find or experience the underlying Unity at a doctrinal or theological level. We can only approach that divine Mystery within by leaving behind all religious dogma and experiencing that divine Reality within the sanctuary of our own hearts.[5]

Impact

Bede Griffiths continues to have an impact through the Bede Griffiths Trust and the Camaldolese Institute for East-West Dialogue based at the American Camaldolese hermitage of New Camaldoli.[6] The archives of the Bede Griffiths Trust are located at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California.

Bibliography

- The Golden String: An Autobiography, (1954), Templegate Publishers, 1980 edition: ISBN 0-87243-163-0, Medio Media, 2003: ISBN 0-9725627-3-7

- Wayne Teasdale, Bede Griffiths: An Introduction to His Interspiritual Thought, Skylight Paths Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-893361-77-2

- Christ in India: Essays Towards a Hindu-Christian Dialogue (1967), Templegate Publishers, 1984, ISBN 0-87243-134-7

- Return to the Center, (1976), Templegate Publishers, 1982, ISBN 0-87243-112-6

- Marriage of East and West: A Sequel to The Golden String, Templegate Publishers, 1982, ISBN 0-87243-105-3

- Cosmic Revelation: The Hindu Way to God, Templegate Publishers, 1983, ISBN 0-87243-119-3

- A New Vision of Reality: Western Science, Eastern Mysticism and Christian Faith, Templegate Publishers, 1990, ISBN 0-87243-180-0

- River of Compassion: A Christian Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, (1987), Element Books, 1995 reprint: ISBN 0-8264-0769-2

- Bede Griffiths, Templegate Publishers, 1993, ISBN 0-87243-199-1

- The New Creation in Christ: Christian Meditation and Community, Templegate Publishers, 1994, ISBN 0-87243-209-2

- Psalms for Christian Prayer, Harpercollins, 1996, ISBN 0-00-627956-2. Co-editor with Roland R. Ropers.

- John Swindells (editor), A Human Search: Bede Griffiths Reflects on His Life: An Oral History, Triumph Books, 1997, ISBN 0-89243-935-1 (from 1992 Australian television documentary)

- Bruno Barnhart, O.S.B. Cam. (editor), The One Light: Bede Griffiths' Principle Writings, Templegate Publishers, 2001, ISBN 0-87243-254-8

- Thomas Matus, O.S.B. Cam. (editor), Bede Griffiths: Essential Writings, Orbis Books, 2004, ISBN 1-57075-200-1

- "The Relation of Ultimate Truth to the Life of the World." Arunodayam (Sep. 1962) 7-9; (Nov. 1962) 5-8.

- "God and the Life of the World: A Christian View." Religion and Society 9/3 (Sep. 1962) 50-58.

- India and the Sacrament. Ernakulam: Lumen Institute, 1964.

- Christian Ashram: Essays towards a Hindu-Christian Dialogue. London: DLT, 1966.

Notes

- ↑ Pascaline Coff OSB, "Man, Monk, Mystic," The Bede Griffiths Trust, at [1]

- ↑ "This man is dangerous", An Overgrown Path website, July 30, 2008 at [2]

- ↑ Renée Weber, Dialogues With Scientists and Sages: The Search for Unity (London and New York, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 163 ISBN 0-7102-0655-0

- ↑ Bede Griffiths and Kenneth Vaux, "Interface Between Christianity and Other Faiths," (Wheaton:Theosophical Publishing House, 1983). CD. Quest Books Web page [3]

- ↑ "Interview with Father Bede Griffiths," (Wheaton:Theosophical Publishing House, 1983). DVD. Quest Books Web page [4]

- ↑ Bede Griffiths' Trust website, [5]