D. H. Lawrence: Difference between revisions

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

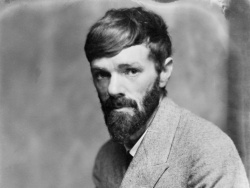

[[File:D H Lawrence.jpg|right|250px|thumb|D. H. Lawrence]] | |||

'''David Herbert Lawrence''' ([[September 11]], 1885 – [[March 2]], 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter. His collected works, among other things, represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. Being part of the Symbolist movement, he was influenced by the [[Theosophy|Theosophical]] literature. | '''David Herbert Lawrence''' ([[September 11]], 1885 – [[March 2]], 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter. His collected works, among other things, represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. Being part of the Symbolist movement, he was influenced by the [[Theosophy|Theosophical]] literature. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 6: | ||

Scholar Michael Ballin states that [[Theosophy]] provided Lawrence with an alternative to two influences in European Western culture that he saw to be equally inimical and destructive: orthodox Christianity and scientific materialism.<ref>Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), ''The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy'' (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 87.</ref> He was also influenced by other Theosophical elements the revaluation of ancient Egypt and Greece wisdom, the [[Religion#Wisdom-Religion|unity of religions]], the mystery of [[Atlantis]] and the correlation between [[Macrocosm and Microcosm|the macrocosm and the microcosm]].<ref>Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), ''The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy'' (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 89, fn.</ref> | Scholar Michael Ballin states that [[Theosophy]] provided Lawrence with an alternative to two influences in European Western culture that he saw to be equally inimical and destructive: orthodox Christianity and scientific materialism.<ref>Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), ''The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy'' (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 87.</ref> He was also influenced by other Theosophical elements the revaluation of ancient Egypt and Greece wisdom, the [[Religion#Wisdom-Religion|unity of religions]], the mystery of [[Atlantis]] and the correlation between [[Macrocosm and Microcosm|the macrocosm and the microcosm]].<ref>Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), ''The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy'' (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 89, fn.</ref> | ||

This Theosophical influence can be seen, for example, in the essays Lawrence wrote interpreting the Bible in a symbolic way. Scholar T. R. Wright states that Lawrence, "while remaining detached from theosophical orthodoxy, can be found to practice a mode of 'double-reading' of the Bible similar to that of Blavatsky and her followers".<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 110</ref> He points out that Blavatsky's interpretation of the role of the serpent in the "fall" of man has "fed into the symbolic significance of much of Lawrence's writing, in particular ''The Plumed Serpent''.<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 119</ref> William York Tindall explored this subject in his book ''D.H. Lawrence and Susan, His Cow'', (1973). | This Theosophical influence can be seen, for example, in the essays Lawrence wrote interpreting the Bible in a symbolic way. Scholar T. R. Wright states that Lawrence, "while remaining detached from theosophical orthodoxy, can be found to practice a mode of 'double-reading' of the Bible similar to that of [[H. P. Blavatsky|Blavatsky]] and her followers".<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 110</ref> He points out that Blavatsky's interpretation of the role of the serpent in the "fall" of man has "fed into the symbolic significance of much of Lawrence's writing, in particular ''The Plumed Serpent''.<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 119</ref> William York Tindall explored this subject in his book ''D.H. Lawrence and Susan, His Cow'', (1973). | ||

Lawrence was also familiar with other Theosophical authors. Wright argues that "probably the most important esoteric book Lawrence read, the one from which he drew the most" is ''Apocalypse Unsealed'', written by Theosophist James A. Pryse.<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 121</ref> However, Lawrence tended to interpret the symbolical figures in a physical and sensual way rather than spiritual. | Lawrence was also familiar with other Theosophical authors. Wright argues that "probably the most important esoteric book Lawrence read, the one from which he drew the most" is ''Apocalypse Unsealed'', written by Theosophist [[James A. Pryse]].<ref>T. R. Wright, ''D. H. Lawrence and the Bible'', (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 121</ref> However, Lawrence tended to interpret the symbolical figures in a physical and sensual way rather than spiritual. | ||

=== Personal correspondence === | === Personal correspondence === | ||

| Line 17: | Line 14: | ||

Lawrence's attitude to the Theosophical teachings, as to other things, was typically irreverent, while at the same time acknowledging its value. This can be seen in some of his correspondence. For example, in a letter to American novelist Waldo David Frank on July 27, 1917, he writes: | Lawrence's attitude to the Theosophical teachings, as to other things, was typically irreverent, while at the same time acknowledging its value. This can be seen in some of his correspondence. For example, in a letter to American novelist Waldo David Frank on July 27, 1917, he writes: | ||

<blockquote>What are you, spiritually? | <blockquote>What are you, spiritually? – Theosophist? I am not a theosophist, though the esoteric doctrines are marvellously illuminating, historically. I hate the esoteric forms. Magic has also interested me a good deal. But it is all part of the past, and part of a past self in us: and it is no good going back, even to wonderful things.<ref>D. H. Lawrence, ''The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921'', vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 143.</ref></blockquote> | ||

In a letter to Dr. David Eder written on August 24, 1917, he says: | In a letter to Dr. David Eder written on August 24, 1917, he says: | ||

<blockquote>Have you read Blavatsky's ''Secret Doctrine''? In many ways a bore, and not quite real. Yet one can glean a marvellous lot from it, enlarge the understanding immensely. Do you know the physical --physiological | <blockquote>Have you read Blavatsky's [[The Secret Doctrine (book)|''Secret Doctrine'']]? In many ways a bore, and not quite real. Yet one can glean a marvellous lot from it, enlarge the understanding immensely. Do you know the physical --physiological – interpretations of the esoteric doctrine? – the chakras and dualism in experience? The devils won't tell one anything, fully.<ref>D. H. Lawrence, ''The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921'', vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 150.</ref></blockquote> | ||

Then again, on November 13, 1918, he wrote to Nancy Henry: | Then again, on November 13, 1918, he wrote to Nancy Henry: | ||

<blockquote>Try and get hold of Mme. Blavatsky's books - they are big and expensive - the friends I used to borrow them from are out of England now. But get from some library or other ''Isis Unveiled'', and better still the 2 vol. work whose name I forget. Rider, the publisher of the Occult Review | <blockquote>Try and get hold of Mme. Blavatsky's books - they are big and expensive - the friends I used to borrow them from are out of England now. But get from some library or other ''Isis Unveiled'', and better still the 2 vol. work whose name I forget. Rider, the publisher of the Occult Review – try that – publishes all these books.<ref>D. H. Lawrence, ''The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921'', vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 298.</ref></blockquote> | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 36: | Line 33: | ||

[[Category:Fiction writers|Lawrence, D. H.]] | [[Category:Fiction writers|Lawrence, D. H.]] | ||

[[Category:Artists|Lawrence, D. H.]] | [[Category:Artists|Lawrence, D. H.]] | ||

[[Category:People|Lawrence, D. H.]] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:27, 7 January 2020

David Herbert Lawrence (September 11, 1885 – March 2, 1930) was an English novelist, poet, playwright, essayist, literary critic and painter. His collected works, among other things, represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanising effects of modernity and industrialisation. Being part of the Symbolist movement, he was influenced by the Theosophical literature.

Theosophical influence

Scholar Michael Ballin states that Theosophy provided Lawrence with an alternative to two influences in European Western culture that he saw to be equally inimical and destructive: orthodox Christianity and scientific materialism.[1] He was also influenced by other Theosophical elements the revaluation of ancient Egypt and Greece wisdom, the unity of religions, the mystery of Atlantis and the correlation between the macrocosm and the microcosm.[2]

This Theosophical influence can be seen, for example, in the essays Lawrence wrote interpreting the Bible in a symbolic way. Scholar T. R. Wright states that Lawrence, "while remaining detached from theosophical orthodoxy, can be found to practice a mode of 'double-reading' of the Bible similar to that of Blavatsky and her followers".[3] He points out that Blavatsky's interpretation of the role of the serpent in the "fall" of man has "fed into the symbolic significance of much of Lawrence's writing, in particular The Plumed Serpent.[4] William York Tindall explored this subject in his book D.H. Lawrence and Susan, His Cow, (1973).

Lawrence was also familiar with other Theosophical authors. Wright argues that "probably the most important esoteric book Lawrence read, the one from which he drew the most" is Apocalypse Unsealed, written by Theosophist James A. Pryse.[5] However, Lawrence tended to interpret the symbolical figures in a physical and sensual way rather than spiritual.

Personal correspondence

Lawrence's attitude to the Theosophical teachings, as to other things, was typically irreverent, while at the same time acknowledging its value. This can be seen in some of his correspondence. For example, in a letter to American novelist Waldo David Frank on July 27, 1917, he writes:

What are you, spiritually? – Theosophist? I am not a theosophist, though the esoteric doctrines are marvellously illuminating, historically. I hate the esoteric forms. Magic has also interested me a good deal. But it is all part of the past, and part of a past self in us: and it is no good going back, even to wonderful things.[6]

In a letter to Dr. David Eder written on August 24, 1917, he says:

Have you read Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine? In many ways a bore, and not quite real. Yet one can glean a marvellous lot from it, enlarge the understanding immensely. Do you know the physical --physiological – interpretations of the esoteric doctrine? – the chakras and dualism in experience? The devils won't tell one anything, fully.[7]

Then again, on November 13, 1918, he wrote to Nancy Henry:

Try and get hold of Mme. Blavatsky's books - they are big and expensive - the friends I used to borrow them from are out of England now. But get from some library or other Isis Unveiled, and better still the 2 vol. work whose name I forget. Rider, the publisher of the Occult Review – try that – publishes all these books.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 87.

- ↑ Jane Campbell and James Doyle (eds.), The Practical Vision: Essays in English Literature in Honour of Flora Roy (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1978), 89, fn.

- ↑ T. R. Wright, D. H. Lawrence and the Bible, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 110

- ↑ T. R. Wright, D. H. Lawrence and the Bible, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 119

- ↑ T. R. Wright, D. H. Lawrence and the Bible, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 121

- ↑ D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921, vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 143.

- ↑ D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921, vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 150.

- ↑ D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence: October 1916-June 1921, vol. III part 1, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 298.