Giordano Bruno: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

Thus, in subsequent centuries, Bruno’s writings enjoyed a revival among scientists and philosophers who saw them as a precursor to the systems of thought. Today, Bruno is remembered more for his courage, his resistance to authority, and his horrible death than he is for his wide range of writings. <ref>Aliprandini, Michael. <i> Giordano Bruno</i> Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition</ref> | Thus, in subsequent centuries, Bruno’s writings enjoyed a revival among scientists and philosophers who saw them as a precursor to the systems of thought. Today, Bruno is remembered more for his courage, his resistance to authority, and his horrible death than he is for his wide range of writings. <ref>Aliprandini, Michael. <i> Giordano Bruno</i> Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition</ref> | ||

The Theosophical Society in Australia operated for a while a commercial broadcasting station beginning in 1926 and named it [[2GB]]. According to the Theosophist [[Clara Codd]], these letters stood for Giordano Bruno, a past incarnation of [[Annie Besant|Dr. Besant]]. | The Theosophical Society in Australia operated for a while a commercial broadcasting station beginning in 1926 and named it [[2GB]]. According to the Theosophist [[Clara Codd]], these letters stood for Giordano Bruno, a past incarnation of [[Annie Besant|Dr. Besant]]. Annie Besant gave on June 15, 1911 a lecture about Giordano Bruno, calling him “Theosophy’s Apostle in the sixteenth century” explaining among many other things that science meant for Giordano Bruno “Occultism, the study of the Divine Mind in Nature, the study of divine Ideas embodied in material objects.” She stated further that “by studying objects, then, it was possible to read the language of Nature, and to learn therein the thoughts of God.” <ref>Besant, Annie. <i>Giordano Bruno, Theosophy’s Apostle in the Sixteenth Century and the Story of Giordano Bruno.</i> A lecture delivered in the Sorbonne at Paris, on June 15, 1911. The Theosophist Office, Adyar, 1913, page 10</ref> | ||

==Online resources== | ==Online resources== | ||

Revision as of 00:09, 2 March 2022

This Article still under Construction

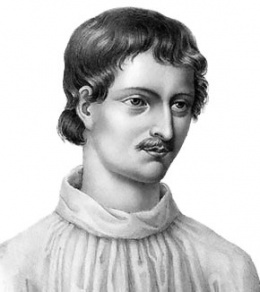

Giordano Bruno (Latin: Iordanus Brunus Nolanus) (1548 – February 17, 1600), born Filippo Bruno, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician, poet, and astrologer. He is celebrated for his cosmological theories, which went even further than the then-novel Copernican model: while supporting heliocentrism, Bruno also correctly proposed that the Sun was just another star moving in space and claimed as well that the universe contained an infinite number of inhabited worlds, identified as planets orbiting other stars. With this Bruno disproved Aristotle’s principal argument for supposing that the universe was finite. It was infinite and eternal. As such, it exhibited all possibilities at any given moment, and all parts of it assumed all possibilities over time, thereby constituting a cognizable manifestation of a timeless and absolute principle, God, conceived as the sole being who truly existed. In keeping with these ideas, Bruno proposed versions of metempsychosis, polygenism, panpsychism and, renouncing Christian emphasis on human imperfection. [1]

Beginning in 1593, Bruno was tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition and on February 17, 1600 he was burned at the stake in Rome's Campo de' Fiori.

Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Arab astrology, Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and the Egyptian god Thoth. [2]

Early Years

Filippo Bruno was born in January or February 1548, son of Giovanni Bruno, a soldier of modest circumstances, and Fraulissa Savolina, at Nola, about 17 miles northeast of Naples. [3] The district he was born in was part of “Greater Greece” and had been a center of Greek philosophy. The tradition of Greek thought and of the doctrines of the neo-platonic School of Alexandria was still loving and potent there. Filippo Bruno was nurtured under the aegis of this philosophy and listened eagerly to the talk of the cultured men who gathered in his father’s house, devoted admirers of the philosophy and ideals of Pythagorean Greece. [4]He began his studies in Nola and continued them in Naples, where he took courses in the humanities and showed a passion for debate with his teachers. His prodigious memory and interest in mnemonic systems were also evident at this early stage.

In 1565, Bruno decided to enter the Dominican Order and assumed the name Giordano. Attached to the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples, he continued his theological studies for the next seven years, at which point he was ordained a priest. He was granted a doctorate in theology in 1575. [5][6]

Giordano Bruno remained in Naples until his twenty-eighth year, until his daring spirit aroused the fear and hostility of the monks, because he read works that were considered heretical and often attacked the precepts of the church. Thus, he was compelled to flee, narrowly escaping the warrant for his arrest. [7] [8] From this time began a life of restless wandering throughout Europe which ended only after sixteen years, when he fell into to power of the Inquisition at Venice. [9]

On the Run

He fled from Naples to Rome and then, taking off his habit, proceeded to northern Italy. He was now a fugitive from his order and excommunicated. Over the next fourteen or so years he moved from one town or city to another, first in Italy and then in France, Switzerland, England, Germany and Bohemia. In 1591 he returned, fatefully, to Venice. It was during these unsettled years that Bruno composed those Italian and Latin works of his that survived till today.

Without family, connections or means of his own, Bruno relied on his wits. [10]

At Noli, in the Gulf of Genua, for example, he taught Latin grammar to schoolboys and elementary astronomy to “certain gentlemen”. [11] In Geneva, he worked in a printer’s shop, correcting proofs.

But his goal was to teach philosophy without the trammels of revealed truths, preferably at a university. [12] Common Knowledge, Volume 14, Issue 3, Fall 2008, pp. 424-433 (Article) </ref> On several occasions, a position of this kind seemed within his grasp. Two factors, however, conspired to thwart his ambitions. The first was the unsettled circumstances of Reformation Europe. At Toulouse, for example, he taught philosophy at the university for nearly two years (1579–81) [13], but renewed conflict between Catholics and Huguenots in the summer of 1581 forced him to leave the city. His notoriety further complicated matters. [14] The second factor was his temperament because he was querulous and intolerant of those whom he deemed fools. This character trait lost him his friends and earned him many enemies. [15]

In 1583 he crossed over to England. In London, Bruno enjoyed the patronage of Queen Elizabeth and developed friendships with several cultural luminaries of the period, including the poet Sir Philip Sidney. Protestant England welcomed Bruno in part because of his disputes with Catholicism. [16] The time in London was one of Bruno’s most productive. He published seven works among them a work about “Remembering”, [17] and a trilogy of dialogues attacking Christianity. In other works, he developed his own spiritual ideas. [18]

Trial for Heresy

Bruno’s wanderings ended abruptly shortly after he returned to Italy in late August 1591. After a brief stay in Venice, he moved to Padua for about three months and then returned to Venice to take up lodgings with the Venetian patrician Giovanni Mocenigo, to whom he divulged the “secrets” of his mnemotechnics and philosophy. There are different opinions about why Mocenigo betrayed him. One source claims he was alarmed at some of Bruno’s views and denounced him to the Venetian Inquisition on May 221592. [19]Others believe that Mocenigo was the infamous tool of the Inquisition and planned the betrayal, [20] [21] while others believe that Mocenigo became increasingly dissatisfied with his teacher, perhaps because he expected Bruno to provide him a magical way to improve and maintain the memory rather than a scholastic way and thus denounced Bruno. [22]

Seven days after Mocenigo’s denunciation the trial began. Mocenigo accused him, “by constraint of his conscience, and by order of his confessor,” of teaching the existence of a boundless universe filled with a countless number of solar systems, that Bruno claimed that the earth was not the center of the universe but a mere planet revolving around the Sun, that he taught the doctrine of reincarnation, that he denied the actual transubstantiation of bread into the flesh of Christ and the he refused to accept the three persons of the Trinity as well as the virgin birth of Christ. [23]

Before the Inquisitors he calmly faced his torturers in their tribunal. Being interrogated, he gave details of his life, and expositions of his philosophy. He spoke of the universe, of the infinite worlds in infinite space, of the divinity in all things, of the unity of all things, the dependence and inter-dependence of all things, and of the existence of God in all. [24] He was carried to Rome, and there he passed eight years in dungeons and torture-chambers.

On January 20, 1600 he was sentenced to be executed without the shedding of blood and said unmoved:

"It is with far greater fear that you pronounce, than I receive, this sentence."

He was burned at the stake on Friday, February 17, 1600. [25][26] Common Knowledge, Volume 14, Issue 3, Fall 2008, pp. 424-433 (Article) </ref>

Even though the Catholic Encyclopedia still claims that Bruno was not condemned for his defense of the Copernican system of astronomy, nor for his doctrine of the plurality of inhabited worlds, but for his theological errors [27]

In the Campo di Fiora, on the spot where Giordano Bruno met his fate stands a monument to his memory. [28] It was erected in 1889 with the robed figure of Bruno facing the Vatican. Church officials rankled at the clear offense but could not get the statue removed.[29]

Bruno’s Afterlife

A few years after his death, Bruno's works (written in both Latin and Italian) were placed on a list of prohibited books and became difficult to find. [30]

Bruno’s philosophy, his views on religion and his execution had earned him notoriety. What perturbed many, including Descartes, was not so much Bruno’s doctrines concerning the earth’s mobility, the elemental homogeneity of the universe, the plurality of worlds and other cosmological innovations, but rather the underlying doctrine of the World Soul and its perceived corollaries: pantheism, demonology, magic, metempsychosis, the claim that God’s absolute power necessitated an infinite product, and the essential identity of human, plant and animal souls. [31]

Demonizing Bruno lent him, however, a certain fascination. During the seventeenth century, his ideas continued to appeal to libertines, Rosicrucians and other unorthodox thinkers, despite, or perhaps because of, the censures of conventional theologians and philosophers. In his Oculus sidereus (Starry Gaze), the Rosicrucian Abraham von Franckenberg (1593–1652), a pupil of Jacob Boehme, wrote that Bruno’s space, was the Kabbalists’ “God as space”, their Ensoph, the first of the ten Sephiroth (Ricci 1990, 137–152). [32]

Thus, in subsequent centuries, Bruno’s writings enjoyed a revival among scientists and philosophers who saw them as a precursor to the systems of thought. Today, Bruno is remembered more for his courage, his resistance to authority, and his horrible death than he is for his wide range of writings. [33]

The Theosophical Society in Australia operated for a while a commercial broadcasting station beginning in 1926 and named it 2GB. According to the Theosophist Clara Codd, these letters stood for Giordano Bruno, a past incarnation of Dr. Besant. Annie Besant gave on June 15, 1911 a lecture about Giordano Bruno, calling him “Theosophy’s Apostle in the sixteenth century” explaining among many other things that science meant for Giordano Bruno “Occultism, the study of the Divine Mind in Nature, the study of divine Ideas embodied in material objects.” She stated further that “by studying objects, then, it was possible to read the language of Nature, and to learn therein the thoughts of God.” [34]

Online resources

Articles

- Giordano Bruno and the Infinite Universe by Warrn Hollister

- Giordano Bruno - A Martyr Theosophist by Charles Johnston

- Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) by Allan J. Stover

- Great Theosophists - Giordano Bruno at WisdomWorld.org

Notes

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 1/17/22

- ↑ Yates, Frances. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London. 1964

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Besant, Annie. Giordano Bruno, Theosophy’s Apostle in the Sixteenth Century and the Story of Giordano Bruno. A lecture delivered in the Sorbonne at Paris, on June 15, 1911. The Theosophist Office, Adyar, 1913, page 4

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 1/17/22

- ↑ Johnston, Charles. Giordano Bruno: A Martyr Theosophist Lucifer Magazine, October 1888. https://universaltheosophy.com/cj/giordano-bruno-martyr-theosophist/ Accessed on 1/13/22

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition – Membership required

- ↑ McIntyre, J. Lewis. Giordano Bruno. London: McMillan and Co, Ltd., New York: The MacMillan Company. 1903, p. 10

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 1/17/22

- ↑ McIntyre, J. Lewis. Giordano Bruno. London: McMillan and Co, Ltd., New York: The MacMillan Company. 1903, p. 11

- ↑ Rowland, Ingrid D. What Giordano Bruno Left Behind: Rome, 1600

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 1/17/22

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. The Secret Teachers of the Western World. Penguin Random House, New York, page 247

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ McIntyre, J. Lewis. Giordano Bruno. London: McMillan and Co, Ltd., New York: The MacMillan Company. 1903, pp. 26-37

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 2/3/22

- ↑ Johnston, Charles. Giordano Bruno: A Martyr Theosophist Lucifer Magazine, October 1888. https://universaltheosophy.com/cj/giordano-bruno-martyr-theosophist/ Accessed on 1/13/22

- ↑ McIntyre, J. Lewis. Giordano Bruno. London: McMillan and Co, Ltd., New York: The MacMillan Company. 1903, pp. 67-68

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Great Theosophists. Giordano Bruno</> In: THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 8, June, 1938. Pages 338-344; Number 23 of a 29-part series. https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/bruno.html. Accessed on 2/2/22

- ↑ Johnston, Charles. Giordano Bruno: A Martyr Theosophist Lucifer Magazine, October 1888. https://universaltheosophy.com/cj/giordano-bruno-martyr-theosophist/ Accessed on 1/13/22

- ↑ Great Theosophists. Giordano Bruno</> In: THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 8, June, 1938. Pages 338-344; Number 23 of a 29-part series. https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/bruno.html. Accessed on 2/2/22

- ↑ Rowland, Ingrid D. What Giordano Bruno Left Behind: Rome, 1600

- ↑ The Catholic Encyclopedia. Giordano Bruno. https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03016a.htm Accessed on 2/20/22<ref>, there is evidence based newly discovered primary sources including treatises on theology, heresies, and Catholic canon law which have only been examined lately, that the belief in many worlds was formally heretical. Thus, Bruno’s belief in many worlds was of primary importance in his trial and execution. <ref>Martinez, Alberto. A. Giordano Bruno and the Heresy of Many Worlds In: Annals of Science, 2016. Vol. 73, No. 4, 345 – 375. Taylor and Francis Group

- ↑ Johnston, Charles. Giordano Bruno: A Martyr Theosophist Lucifer Magazine, October 1888. https://universaltheosophy.com/cj/giordano-bruno-martyr-theosophist/ Accessed on 1/13/22

- ↑ Campo di Fiori. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/campo-de-fiori Accessed on 2/20/22

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 2/20/22

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Giordano Bruno May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/ Accessed on 2/20/22

- ↑ Aliprandini, Michael. Giordano Bruno Great Neck Publishing. 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition

- ↑ Besant, Annie. Giordano Bruno, Theosophy’s Apostle in the Sixteenth Century and the Story of Giordano Bruno. A lecture delivered in the Sorbonne at Paris, on June 15, 1911. The Theosophist Office, Adyar, 1913, page 10