Simla, India: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Simla''', pronounced '''Shimla''', was the summer capital of India during the British Raj. The modern spelling is '''Shyamala'''. It is located in the state of Himachal Pradesh an elevation of 7,116 feet (2,169 m) in the foothills of the Himalayas. The mountainous terrain provided a climate that was much more tolerable to Europeans than the capital city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) during the summer monsoon. No railway was available until the Kalka-Shimla Railway was completed in 1903.<ref>"Kalka-Simla Railway," [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalka-Shimla_Railway Wikipedia].</ref> Early Theosophists in India would have travel by cart to reach the city. | |||

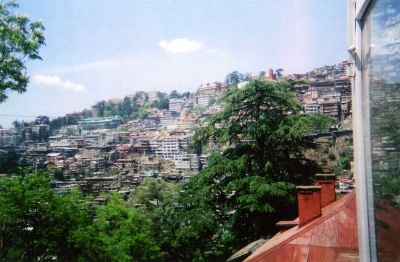

These photographs from May 2006 were provided by Michael Gomes. | |||

{|style="margin: 0 auto;" | |||

| [[File:Simla view by MG May 2006.jpg|400px]] [[File:Simla by MG May 2006.jpg|400px]] | |||

|} | |||

In the early pages of his novel ''Mr. Isaacs'', [[Francis Marion Crawford]] wrote of Simla: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

To Simla the whole supreme Government migrates for the summer—Viceroy, council clerks, printers, and hangers-on. Thither the high official from the plains takes his wife, his daughters, and his liver. There the journalists congregate to pick up the news that oozes through the pent-house of Government secrecy, and failing such scant drops of information, to manufacture as much as is necessary to fill the columns of their dailies. On the slopes of "Jako"—the wooded eminence that rises above the town—the enterprising German establishes his concert-hall and his beer-garden; among the rhododendron trees Madame Blavatzky, Colonel Olcott and Mr. Sinnett move mysteriously in the performance of their wonders; and the wealthy tourist from America, the botanist from Berlin,and the casual peer from Great Britain, are not wanting to complete the motley crowd. There are no roads in Simla proper where it is possible to drive, excepting one narrow way, reserved when I was there, and probably still set apart, for the exclusive delectation of the Viceroy. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

'''Simla''', pronounced | |||

< | |||

< | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[es: Simla]] | [[es: Simla]] | ||

[[Category:Places]] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:33, 8 September 2023

Simla, pronounced Shimla, was the summer capital of India during the British Raj. The modern spelling is Shyamala. It is located in the state of Himachal Pradesh an elevation of 7,116 feet (2,169 m) in the foothills of the Himalayas. The mountainous terrain provided a climate that was much more tolerable to Europeans than the capital city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) during the summer monsoon. No railway was available until the Kalka-Shimla Railway was completed in 1903.[1] Early Theosophists in India would have travel by cart to reach the city.

These photographs from May 2006 were provided by Michael Gomes.

|

In the early pages of his novel Mr. Isaacs, Francis Marion Crawford wrote of Simla:

To Simla the whole supreme Government migrates for the summer—Viceroy, council clerks, printers, and hangers-on. Thither the high official from the plains takes his wife, his daughters, and his liver. There the journalists congregate to pick up the news that oozes through the pent-house of Government secrecy, and failing such scant drops of information, to manufacture as much as is necessary to fill the columns of their dailies. On the slopes of "Jako"—the wooded eminence that rises above the town—the enterprising German establishes his concert-hall and his beer-garden; among the rhododendron trees Madame Blavatzky, Colonel Olcott and Mr. Sinnett move mysteriously in the performance of their wonders; and the wealthy tourist from America, the botanist from Berlin,and the casual peer from Great Britain, are not wanting to complete the motley crowd. There are no roads in Simla proper where it is possible to drive, excepting one narrow way, reserved when I was there, and probably still set apart, for the exclusive delectation of the Viceroy.