Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

<b>Human Beings No. 5</b> have fully developed and properly equilibrated all their lower centers. They are continuously in the state of self-consciousness and have glimpses of the unitive vision. | <b>Human Beings No. 5</b> have fully developed and properly equilibrated all their lower centers. They are continuously in the state of self-consciousness and have glimpses of the unitive vision. | ||

<b>Human Beings No. 6 </b>truly know themselves; they are permanently in the state of self-consciousness and have made contact with their higher centers. | <b>Human Beings No. 6 </b>truly know themselves; they are permanently in the state of self-consciousness and have made contact with their higher centers. They have acquired everything but permanence. | ||

<b>Human Beings No. 7 </b>are the ones who have perfected themselves. They have free will, objective consciousness, a permanent “I”, and their own willpower. Whatever they want is always seen from and in the service of “Endlessness”. <ref>Ginsburg, B. Seymor. <i>Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO | <b>Human Beings No. 7 </b>are the ones who have perfected themselves. They have free will, objective consciousness, a permanent “I”, and their own willpower. Whatever they want is always seen from and in the service of “Endlessness”. <ref>Ginsburg, B. Seymor. <i>Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

1. To strive to have everything satisfying and really necessary for our planetary body. | 1. To strive to have everything satisfying and really necessary for our planetary body. | ||

2. To strive constantly for self-perfection in the sense of being. | 2. To strive constantly for self-perfection in the sense of being. | ||

To strive to know ever more concerning the laws of world-creation and world-maintenance. | 3. To strive to know ever more concerning the laws of world-creation and world-maintenance. | ||

[These are the laws governing the structure of ourselves (the | [These are the laws governing the structure of ourselves (the | ||

microcosm) and the larger universe of which we are a reflection (the macrocosm)]. | microcosm) and the larger universe of which we are a reflection (the macrocosm)]. | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

[[File: Gurdjieff_Movements.jpg|right|260px|thumb|Gurdjieff Movements]] | [[File: Gurdjieff_Movements.jpg|right|260px|thumb|Gurdjieff Movements]] | ||

The “sacred dances” or “Movements” were first revealed by Gurdjieff in 1919 in Tiflis | The “sacred dances” or “Movements” were first revealed by Gurdjieff in 1919 in Tiflis, the site of the first foundation of his <i>Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man</i>. The proximate cause of this new teaching technique has been hypothesized to be Jeanne de Salzmann (1889–1990), an instructor of the Eurhythmics method of music education developed by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950). Jeanne and her husband Alexandre met at Jaques-Dalcroze’s Institute at Hellerau in 1913 and became pupils of Gurdjieff in 1919. It was to her Dalcroze class that Gurdjieff first taught Movements. | ||

When Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky (1878–1947) met | When Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky (1878–1947) met Gurdjieff in 1915, he spoke of dances he had seen in Eastern temples, and was working on a never-performed ballet, <i>The Struggle of the Magicians</i>. Research shows, that body-based disciplines introduced by esoteric teachers with Theosophically-inflected systems are a significant phenomenon in the early twentieth century and that Gurdjieff’s Movements, while distinct from other dance systems, emerged in the same esoteric melting-pot and manifest common features and themes with the esoteric dance of Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf von Laban, PeterDeunov, and others. <ref>Cusack, Carole. <i>The Contemporary Context of Gurdjieff’s Movements.</i> University of Sydney. In: Religion and the Arts 21 (2017) 96-122</ref> | ||

he had seen in Eastern temples, and was working on a never-performed ballet, <i>The | |||

Struggle of the Magicians</i>. Research shows, that body-based disciplines introduced by esoteric teachers with Theosophically-inflected systems are a significant phenomenon in the early twentieth century and that Gurdjieff’s Movements, while distinct from other dance systems, emerged in the same esoteric melting-pot and manifest common | |||

features and themes with the esoteric dance of Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf von Laban, | |||

The role of the movements is nothing less than to bring attention to the whole person - body, mind and feelings, while maintaining a level of consciousness of one's surroundings-- the teacher's instructions, the other pupils, the music. | The role of the movements is nothing less than to bring attention to the whole person - body, mind and feelings, while maintaining a level of consciousness of one's surroundings-- the teacher's instructions, the other pupils, the music. | ||

Revision as of 11:53, 15 April 2024

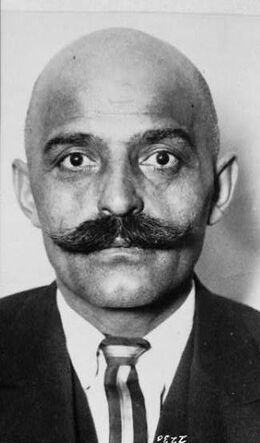

Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff was a mystic, philosopher, esoteric writer, spiritual teacher, composer, and choreographer of Armenian and Greek descent. He was born in Alexandropol, Armenia (back then part of the Russian Empire) in the late 19th century, with his birth date often cited as January 13, 1866. He is best known for his teachings on self-awareness and self-improvement, which he referred to as "The Work" or "The Fourth Way." Gurdjieff worked first in Russia and later in France and became known as a teacher and founder of a worldwide and widespread following.

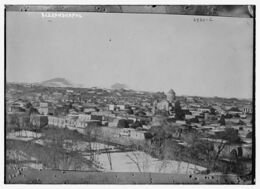

Gurdjieff established the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in 1919 at Tiflis (now Tbilisi), Georgia, where he taught his ideas through a combination of lectures, music, dance (Movements), and group work. It was reestablished at Fontainebleau, France, in 1922. [1]

Gurdjieff is known for his charismatic personality and idiosyncratic, improvisatory methods of teaching. His life and teachings have been explored and critiqued in countless publications. [2]

Some of his students called the Gurdjieff approach “A method of Conscious Effort and Voluntary Suffering against INERTIA and REPETITION.” He died on October 29, 1949, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. His legacy continues through the work of various Gurdjieff foundations and groups around the world. [3]

Early Life

The very date of Gurdjieff’s birth is in dispute, although he himself stipulates 1866. [4] Between his birth and 1912 biographers have to be reliant on Gurdjieff's own four impressionistic accounts, which are not very consistent. Notoriously problematical are 'the missing twenty years' from 1887 to 1907. [5]

Based on Gurdjieff’s account, he grew up in the volatile Caucasus region located between Christian Orthodox Russia and Islamic Turkey, Iraq, and Persia. His family moved from Alexandropol to Kars shortly after its recapture by Russia from the Turks. There he was tutored by the Dean of the Russian Orthodox Cathedral and later by Bogachevsky, a candidate for the priesthood, who tutored him in the Christian precepts. Gurdjieff revered this teacher all his life.

Coming "to the whole sensation" of himself at an early age and recognizing the mindless mechanicality of human life, the question arose within Gurdjieff—what is the meaning and purpose of life on earth and of human life in particular?[6]

Gurdjieff's search for such knowledge led him to travel widely, seeking out sacred cities and sites throughout the Middle East and Central Asia in pursuit of esoteric knowledge. The only account of his wanderings appears in his book Meetings with Remarkable Men.[7] He arrived in Moscow in 1912 with the groundwork for his teaching formulated and started gathering pupils. He founded an Institute in 1918 in Essentuki in the Caucasus, which eventually became the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Tiflis. Later it was moved to Constantinople, Berlin, and finally, in October 1922, it opened at the Château Le Prieuré at Fontainebleau-Avon where it functioned until 1932. [8]

Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man

Gurdjieff first established the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Manin 1919 at Tiflis (now Tbilisi), Georgia, where he taught his ideas through a combination of lectures, music, dance (Movements), and group work. [9]

After escaping the Russian revolution with dozens of followers and family members, Gurdjieff settled in France and reestablished the Institute for Harmonious Development of Man at the Château Le Prieuré at Fontainebleau-Avon in October of 1922.

Gurdjieff was of the opinion that modern man's world perception and his own mode of living are not the conscious expression of his being taken as a complete whole. Quite on the contrary, they are only the mechanical manifestation of one or another part of him.

Thus, members living at the institute, many from prominent backgrounds, lived a virtually spartan life, except for a few banquets, at which Gurdjieff would engage in probing dialogue and at which his writings were read. Ritual exercises and dance were also part of the regimen, often accompanied by music composed jointly by Gurdjieff and an associate, the composer Thomas de Hartmann. Performers from the institute appeared in Paris in 1923 and in three U.S. cities the following year and brought considerable attention to Gurdjieff’s work. [10]

Gurdjieff’s Work and Ideas

The Fourth Way

Gurdjieff's Fourth Way is a spiritual teaching that combines elements of Eastern and Western philosophy and religion. It is called the Fourth Way because it is said to be a path that integrates the three traditional ways of spiritual development:

the way of the fakir (physical discipline), the way of the monk (emotional devotion), and the way of the yogi (mental concentration).

The Fourth Way emphasizes the development of consciousness and self-awareness while living an ordinary life in the world, rather than through withdrawal from the world as in monastic or ascetic practices. Gurdjieff believed that most people live their lives in a state of "waking sleep," and that true spiritual awakening requires conscious effort and work on oneself.

Key concepts of the Fourth Way include:

1. Self-observation: Paying attention to one's thoughts, emotions, and actions in the present moment without judgment or identification. Gurdjieff also called this “conscious suffering”.

2. Self-remembering: A practice of maintaining awareness of oneself and one's surroundings simultaneously, to be present and not lost in identification with thoughts or emotions.

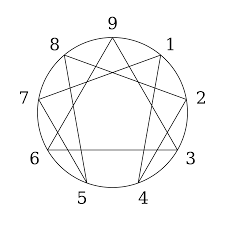

3. The Enneagram: A geometric symbol used as a tool for understanding the dynamics of personality and the processes of transformation.

4. Three Centers: The idea that humans have three centers of functioning - intellectual, emotional, and physical - and that balanced development of these centers is essential for spiritual growth.

5. Identification and Non-identification: Learning to detach from identifying with one's thoughts, emotions, and roles in life.

6. Internal and External Considering: Balancing one's own needs and interests with those of others in interactions.

Gurdjieff's teachings were not systematic and were often transmitted orally through direct work with his students. He used various methods, including group work, music, dance (Movements), and practical tasks, to help students develop self-awareness and inner growth.

The Fourth Way has influenced various spiritual and self-development movements and continues to be studied and practiced by groups around the world. [11] [12][13][14][15]

The Enneagram

Gurdjieff introduced the enneagram to the modern world in 1914, stating that it is a schematic diagram that was preserved in secret for a long time and could only be understood by those who knew it meaning. [16] It can be traced back at least as far as the works of Pythagoras. [17] The Enneagram is a symbol and a concept that plays a significant role in Grudjieff’s teachings. It is a nine-pointed geometric figure that Gurdjieff introduced to his students as a tool for understanding the laws governing the universe and human behavior. Each point on the Enneagram is said to represent a specific type of process or function, and the interactions among these points are used to describe the dynamics of various systems, including psychological, cosmological, and spiritual systems. Under Gurdjieff, the Enneagram was a tool for teaching his students about the dynamics of self-development and spiritual growth and was not used as a personality typing system, which is a common modern interpretation of the Enneagram. Instead, it is a symbol of the unity of the laws of the universe, representing the interconnection of the laws of three and seven, which Gurdjieff referred to as the Law of Three and the Law of Seven or the Law of Octaves. These laws describe the fundamental principles of transformation and evolution in the universe. [18][19]

The Law of Three and the Law of Seven

Gurdjieff's Law of Three and the Law of Seven are central to his teachings and are integral to understanding the Enneagram and the dynamics of transformation in the universe according to his philosophy. Law of Three: It states that every phenomenon in the universe is a result of the interaction of three forces: the active force, the passive force, and the neutralizing or reconciling force. These forces are also referred to as affirming, denying, and reconciling, or positive, negative, and neutral. In Gurdjieff's view, these three forces are present in every action, every process, and every moment of existence. The active force initiates or propels, the passive force resists or receives, and the neutralizing force harmonizes or balances the interaction between the active and passive forces. This triadic principle is seen as a fundamental law governing all levels of reality, from the cosmic to the human. Law of Seven:The Law of Seven, or the Law of Octaves, is based on the idea that all processes in the universe unfold in a sequence of seven stages or intervals. This law is related to the musical octave, where the eighth note is a higher repetition of the first note, completing the cycle. According to Gurdjieff, every process undergoes a development that can be divided into seven stages, each with its own characteristics. However, this development is not linear; it is subject to certain "shocks" or discontinuities that occur at specific intervals (between the third and fourth stages and between the sixth and seventh stages). These shocks are necessary for the process to continue its development and move to the next level. The Law of Seven is used to explain the dynamics of various processes, including psychological development, the unfolding of historical events, and the evolution of consciousness. It is also reflected in the structure of the Enneagram, where the points are connected in a sequence that represents the intervals of the octave. Both the Law of Three and the Law of Seven are essential for understanding Gurdjieff's view of the cosmos and the inner workings of the human being. They are interrelated and together form the basis of his teaching on the dynamics of transformation and the possibility of reaching a higher level of being. ref>Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1</ref>[20]

Seven Different Levels of Human Beings

Gurdjieff suggested that the only real evolution is the evolution of consciousness and that human consciousness can be divided into four distinct states, each relatively more conscious than the preceding state.

He divided human beings into seven categories, each with its own level of consciousness.

Human Beings No. 1 are the physical beings, No. 2 the emotional beings and No. 3 the intellectual beings. They are all on the same level but of different types, reacting differently to the same stimuli. None is better than the other – they are all at the same level of consciousness.

Human Beings No. 4 are transitional. They know what they want and need, they have a well-defined aim constantly in sight and all action are in relation to this aim. They are balanced physically, emotionally, and intellectually and continuously work on themselves.

Human Beings No. 5 have fully developed and properly equilibrated all their lower centers. They are continuously in the state of self-consciousness and have glimpses of the unitive vision.

Human Beings No. 6 truly know themselves; they are permanently in the state of self-consciousness and have made contact with their higher centers. They have acquired everything but permanence.

Human Beings No. 7 are the ones who have perfected themselves. They have free will, objective consciousness, a permanent “I”, and their own willpower. Whatever they want is always seen from and in the service of “Endlessness”. [21]

Strivings

Gurdjieff stated, that by the very fact of their existence and possibilities, every human being has duties. He set out five injunctions, which he called the “being-obligolnian-strivings. [22]

In contemporary language they are: 1. To strive to have everything satisfying and really necessary for our planetary body. 2. To strive constantly for self-perfection in the sense of being. 3. To strive to know ever more concerning the laws of world-creation and world-maintenance. [These are the laws governing the structure of ourselves (the microcosm) and the larger universe of which we are a reflection (the macrocosm)]. 4. To strive to pay for our arising and individuality as quickly as possible. 5. To strive to assist the most rapid perfecting of other beings, both those similar to ourselves and those of other forms.[23]

Perhaps the essence of each injunction could be described as: 1. Physical health

2. Conscious development of being

3. Understanding of the nature and purpose of creation

4. Payment for what one has received and achieved

5. Service, or “helping God.” [24]

The Movements

The “sacred dances” or “Movements” were first revealed by Gurdjieff in 1919 in Tiflis, the site of the first foundation of his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man. The proximate cause of this new teaching technique has been hypothesized to be Jeanne de Salzmann (1889–1990), an instructor of the Eurhythmics method of music education developed by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865–1950). Jeanne and her husband Alexandre met at Jaques-Dalcroze’s Institute at Hellerau in 1913 and became pupils of Gurdjieff in 1919. It was to her Dalcroze class that Gurdjieff first taught Movements.

When Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky (1878–1947) met Gurdjieff in 1915, he spoke of dances he had seen in Eastern temples, and was working on a never-performed ballet, The Struggle of the Magicians. Research shows, that body-based disciplines introduced by esoteric teachers with Theosophically-inflected systems are a significant phenomenon in the early twentieth century and that Gurdjieff’s Movements, while distinct from other dance systems, emerged in the same esoteric melting-pot and manifest common features and themes with the esoteric dance of Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf von Laban, PeterDeunov, and others. [25]

The role of the movements is nothing less than to bring attention to the whole person - body, mind and feelings, while maintaining a level of consciousness of one's surroundings-- the teacher's instructions, the other pupils, the music.

Gurdjieff stated in his first talk in Berlin in 1921:

You ask about the aim of the movements. To each position of the body corresponds a certain inner state and, on the other hand, to each inner state corresponds a certain posture. A man, in his life, has a certain number of habitual postures and he passes from one to another without stopping at those between. Taking new, unaccustomed postures enables you to observe yourself inside differently from the way you usually do in ordinary conditions. ”[26].

The feature film Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979), loosely based on Gurdjieff's book by the same name, ends with performances of Gurdjieff's dances known simply as the "exercises" but later promoted as movements. Jeanne de Salzmann and Peter Brook wrote the film and Brook directed it. [27] [28]

The Music

Music played a tremendous role in the life of Gurdjieff. A large and diverse body of music he composed with Ukrainian composer and pupil Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (1885-1956). [29] The music of Gurdjieff / de Hartmann is the result of an extraordinary collaboration. They composed three categories of piano music - Asian and eastern folk music, Sayyid and Dervish music, and hymns and served the advancement of self-understanding through esoteric practice. According to Gurdjieff, the deliberation of music in various forms can serve the functions of self-study and inquiry into attention. From 1923 to 1929, Thomas de Hartmann worked closely with Gurdjieff at his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man outside Paris, translating into European notation the music Gurdjieff composed from his travels. [30] Gurdjieff composed three types of music: Piano Music with de Hartmann The Music of Movements (dances and exercises choreographed by Gurdjieff) and Harmonium Music. [31] In his autobiographical writings Gurdjieff describes his great admiration for the musical abilities of the “ashokhs”, or travelling bards, a profession of his father, which had fascinated him as a young boy in Kars, Turkey. [32]During his extensive travels as a young man he also described playing, singing, hearing, recording, and memorizing music, as well as becoming enthralled in the effects and properties of vibrations of sound and music. [33] In his teaching years Gurdjieff incorporated singing and other musical exercises into his pedagogy and based his cosmology on musical analogues. He collaborated with de Hartmann on their piano music and music for Movements, and in the last twenty years of his life when de Hartmann had left him, Gurdjieff consistently relied on his portable harmonium, playing music for groups of pupils and accompanying readings of his texts. [34] One can listen to one of the most memorable musical pieces in the film “Meetings with Remarkable Men”. It is the "Gurdjieff Folk Instruments Ensemble," which features traditional instruments and melodies and was formed to perform the music of Gurdjieff and Thomas de Hartmann, who collaborated on a large body of piano music based on the folk and spiritual music of the regions Gurdjieff had traveled.

Writings

Eventually Gurdjieff turned his energies to the writing down of his teaching, mainly in allegorical form through his magnus opus with the title All and Everything. It was published in three series, the first part being Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson (1950) which Gurdjieff rewrote several times based on feedback from his students. This book is considered his masterpiece. [35]

Meetings with Remarkable Men is the second volume. Published posthumously in 1963, the book is part autobiography and part spiritual narrative. Gurdjieff writes about his travels over a period of twenty years 23 with a group of companions called „Seekers of the Truth‟, whose principle was “never to follow the beaten track.” [36]

The book is a series of vignettes, recounting Gurdjieff's encounters with various extraordinary individuals ("remarkable men") who significantly influenced his early life and spiritual journey. These encounters are said to have taken place during Gurdjieff's extensive travels in Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, in his search for ancient wisdom and esoteric teachings.

The third part is titled Life is Real only Then, When “I am” (1975) and contains notes on talks Gurdjieff gave between 1914 and 1930. The introduction to the paperback edition indicates that “The Talks have been compared and regrouped with the help of Madame de Hartmann, who from 1917 in Essentuki was present at all these meetings and could thus guarantee their authenticity.” These notes provide a vital record of the fluid, ‘search-demanding,’ approach inherent in the oral tradition Gurdjieff emerged from and maintained. [37]

The system of ideas he taught from 1914 to 1924 was faithfully recorded and published in P.D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous (1949) and also in notes, principally of Jeanne de Salzmann, presented in Views from the Real World (1974). [38]

Gurdjieff and Theosophy

H. P. Blavatsky and Gurdjieff were pioneers in reviving occult traditions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and in introducing Eastern religious and philosophical ideas to the West. Both attributed their teachings to the esoteric knowledge that they accumulated on their extensive travels in what were then regarded as remote and sacred locations of the world.

Gurdjieff made remarks, all disparaging, about Theosophy throughout his writings, which were no doubt designed to promote his own method over that of Theosophy. [39]

Even though Gurdjieff repudiated the Theosophical movement, it appears that he directly drew from Theosophy, which was essentially the basis for the occult revival in Russia. Gurdjieff formulated his teachings between 1912 and 1916, and the Russian Theosophical Society was at the pinnacle of its success and influence during that time. Further, Gurdjieff formulated his teachings in Moscow and St. Petersburg, which were major centers for the occult revival.

In Gurdjieff’s writings and talks, one finds distinctive phrases and terms popularized by Theosophy at the time, like “emerald tablet,” “alchemy,” and “astral bodies”. There is also a clear parallel between approaches of Blavatsky and Gurdjieff to the composition of the human being, which represented for both a microcosm manifesting the threefold and sevenfold structure of the macrocosmic universe. [40]

In addition, he described his system as “esoteric Christianity”, a term associated with well-known Theosophists at that time.

However, Gurdjieff emphasizes practical work in his teachings, particularly work with the body, whereas Theosophy focuses on humans working their way out of material existence. And it could be possible that both movements drew on common esoteric currents prominent at that time in Russia.

It is also noteworthy that some of Gurdjieff’s closest pupils, such as Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky (1878-1947), Alfred Richard Orage (1873-1934), Olga and Thomas de Hartmann and Alfred Trevor Parker, had strong ties to Theosophy. Some of them were even members of the Theosophical Society. [41]

For example, Ouspensky gave lectures on Gurdjieff's teaching at the Theosophical Society in London. Andrew Barker, while staying at the Prieuré in Paris, was editing the Mahatma Letters in preparation for their publication in 1923. [42]

Gurdjieff’s Most Famous Students

When Thomas de Hartmann (1885–1956) met Mr. Gurdjieff in 1917, he was already an acclaimed composer in St. Petersburg. Between July 1925 and May 1927 he transcribed and co-wrote some of the music that Gurdjieff collected and used for his Movements exercises. He and Gurdjieff collaborated on hundreds of pieces of concert music arranged for the piano. [43][44]

Thomas de Hartmann and his wife Olga de Hartmann (1885–1979 )remained Gurdjieff's close students until 1929. During that time, they lived at Gurdjieff's Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man near Paris. Olga de Hartmann was Gurdjieff’s personal secretary. She was a major figure in the transmission of the teachings of Gurdjieff. Having met Gurdjieff in 1917, she worked with him intensely in very trying and even dangerous conditions. [45] [46]

Henry Maurice Dunlop Nicoll (1885 – 1953) was born in Scotland on July 19, 1885. He studied medicine at Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, qualified as a surgeon and neurologist, then traveled to Buenos Aires as a Ship’s Surgeon. [47]. After his return he spent a year abroad to study psychology and he later told his pupils that a visit with Dr. C.G. Jung was “the first important event in his life.” [48] Jung cured Nicoll of his stammer and became a lifelong close friend.

During World War I, Nicoll volunteered and served as a medical doctor under extremely challenging circumstances. These experiences made him acutely aware of “injuries of the mind.” In 1921 Nicoll heard a lecture by P. Ouspensky. He returned home “transformed, as though irradiated by an inner light” according to a comment made by his wife. “This new link caused Dr. Nicoll to break his official connection with Dr. Jung who had hoped at one time that he would act as the chief exponent of his psychology in London.” [49]

Gurdjieff visited Ouspensky’s group in London in 1922, whereupon they collected the money with which the Prieuré was purchased. In November of that year, Dr. Nicoll gave up his Harley Street practice and moved to Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man with his wife and infant daughter. He remained there until it closed.

Upon returning to London to rebuild his practice, Nicoll and his wife resumed attending Ouspensky’s meetings three times a week for the next 7 years. A strong relationship developed “because Dr. Nicoll was the only one of this group who would really speak to him emotionally of what he had said at a meeting.” [50] In 1931 Ouspenksy authorized Dr. Nicoll to start his own group which Nicoll did, and developed a style that was his own—not flashy, but profoundly present and sincere. He “recollected what he could of Gurdjieff’s music and Jessmin Howarth and Rosemary Nott taught the Movements.”[51]

BePeriod, published by Asaf Braverman, describes Nicoll as follows: “Dr. Maurice Nicoll’s work within the body of Fourth Way literature arguably represents the most complete, organized, and computational presentation available on the subject. His lucid formatting of the whole network of linked ideas is totally faithful to the name given by Ouspensky to the encapsulated collection of teachings coming from Gurdjieff and the near East: the system.”[52]

Alfred Richard Orage (1873-1934) sold his famous journal The New Age to work with the mystic G. Gurdjieff in France. He wanted to come to a more fundamental understanding of the human species. Orage worked intensively for more than a year with Gurdjieff in his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, and it seems that he had found what he was seeking. Gurdjieff, on the other hand, found in Orage someone whom he considered a brother in spirit.

When Gurdjieff expanded his activities into the New World, Orage became his emissary there. Orage arrived in New York in December 1923 to expound Gurdjieff's ideas, and until 1931, was talking to a growing group of interested people. [53]

Pyotr D. Ouspensky (1878-1947) was a Russian journalist, author, and philosopher. He met Gurdjieff in 1915 [54] and spent the next five years studying with him, then formed his own independent groups at London in 1921. Ouspensky became the first "career" Gurdjieffian and led independent Fourth Way groups in London and New York for his remaining years. He wrote In Search of the Miraculous about his encounters with Gurdjieff and it remains the best known and most widely read account of Gurdjieff's early work with groups. “This work is by far the most lucid account available of the Russian period of Gurdjieff's teaching, and it has been a principal cause of the growing influence of Gurdjieff's ideas.” [55]

Jeanne de Salzmann (1889 - 1990) was born in Reims, France and was brought up in Switzerland. She married her husband, Alexandre de Salzmann, a well-known Russian painter, in 1912 and moved with him to Tiflis in the Caucasus, where she met Gurdjieff in 1919. In Gurdjieff and his teaching Jeanne de Salzmann found the way toward the truth she had longed for since childhood.

Jeanne de Salzmann was deeply committed to Grudjieff and his work. She played the principal role in Gurdjieff’s introduction and practice of the dance exercises called the “Movements”. She worked with him in Tiflis, Paris, and New York. Before Gurdjieff died, he charged Mme. De Salzmann to live to be “over 100” in order to establish his teaching and left her all his rights with respect to his writings and the Movements, as well as the music that de Hartmann had composed with him. During the next forty years she arranged for publication of his books and preservation of the Movements. She also established Gurdjieff centers in Paris, New York, London, and Caracas. She published the book The Reality of Being.[56]

The book is organized according to themes, the chapters touch on all the important concepts and practices of the Work. Madame de Salzmann brings to the Work her own strong, direct language and personal journey in learning to live that knowledge of a higher level of being, which, she insists, “you have to see for yourself” on a level beyond theory and concept. De Salzmann consistently refused to discuss the teaching in terms of ideas, for this Fourth Way is to be experienced, not simply thought or believed.[57]

Final Years

Even though his final years were not so much in the public eye, Gurdjieff appears to have been sought out and surrounded by pupils. It is during this time that he laid the foundations of the Gurdjieff groups, which still exist. From1941 till 1946, he worked intensely with French groups and from 1946 till 1949 he had visitors from various groups from the UK and the USA.

Gurdjieff seems never again to have taught his ideas with the exhaustive range that he did in Russia, yet some of his methods, such as the music, the Sacred Dances or Movements, and the “contemplation-like exercises” with which this book deals were either introduced or developed after the Russian period. Their foundations are found in that earlier teaching, thus evidencing continuity in Gurdjieff’s teaching. [58]

However, by the time of his final ten years in Paris (1939-1949), he seems to have been balanced; he was more consistent, and he was consolidating his work. He still possessed all the knowledge and being he had ever had, if not more. But by this time his physical energy was diminishing.[59]

Gurdjieff died the morning of October 29, 1949. William Welch, his American doctor, said, "I have seen many men die. He died like a king." [60]

Assessment

It is difficult to sum up Gurdjieff and his teachings, partly because he wanted to be enigmatic. [61] Many researchers trace diverse aspects of Gurdjieff’s teachings to different sources, viewing him as a synthesizer, who disguised his debt to Western Esotericism and presented it as his “Fourth Way”. [62]

However, it seems that Gurdjieff has not even been satisfactorily understood let alone investigated by some researchers, ignoring Gurdjieff’s achievement for example, his music and Movements and Sacred Dances. [63]

As with all Gurdjieff wrote and said, there is a level of lived experience that makes this teaching warranting of deep pause. Things that might appear homiletic in the mouth of a lesser figure took on life-and-death seriousness from this teacher. [64]

Because of his complex and paradoxical teachings, Gurdjieff remains one of the first gurus of spiritual self-help in the West. In All and Everything he stated, one must “work on an all-round knowledge of oneself.” [65] He also used to say, ‘Man must live till he dies,’ by which he meant that man should consciously labor and voluntarily suffer in order to achieve true spiritual growth—and he not only believed it but put it into practice. In many ways “Gurdjieff was years ahead of his time”. [66][67]

One thing that stands out. Despite the fact that he had to go through many challenging experiences - he had to flee his homeland because of the Russian Revolution, he experienced World War I and World War II, was in Paris during the Nazi occupation, had two car accidents and very serious injuries (1924 and 1948) – Gurdjieff never lost his aim and kept teaching.

Notes

- ↑ Britannica. George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Ivanovitch-Gurdjieff. Accessed on 3/9/24

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna.A Gurdjieff Genealogy: Tracing the manifold Ways the Gurdjieff Teaching has travelled.International Journal for the Study of New Religions, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2013

- ↑ Anderson, Margaret. The Unknowable Gurdjieff. Penguin Books Ltd., London, England. 1962

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Moore, James. Gurdjieff Chronology. https://www.gurdjieff.org/chronology.htm Accessed on 3/12/24

- ↑ Gurdjieff’s Early Years.THE GURDJIEFF LEGACY FOUNDATION: The Teaching for our Time. https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/70links/early_years.htm Accessed on 3/18/24

- ↑ Owens, Terry Winter.All and Everything – Meetings with Remarkable Men. Gurdjieff International Review. https://www.gurdjieff.org/owens2.htm. Accessed on 4/2/24

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. A Gurdjieff Genealogy: Tracing the Manifold Ways the Gurdjieff Teaching Has Travelled. In: International Journal for the Study of New Religions, Vol. 4, No. 2013.

- ↑ Britannica. George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Ivanovitch-Gurdjieff. Accessed on 3/9/24

- ↑ Britannica. George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Ivanovitch-Gurdjieff. Accessed on 3/2/24

- ↑ Ouspensky, P.D. The Fourth WayVintage; New edition, February 12, 1971.

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Oxford Academic Books. 2 An Overview of Gurdjieff’s Ideas. December 2019

- ↑ de Salzmann, Jeanne. THE REALITY OF BEING: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff.Shambhala, Boston & London, 2011

- ↑ Anderson, Margaret. The Unknowable Gurdjieff. Penguin Books Ltd., London, England. 1962

- ↑ Jones, Constanze. California Institute of Integral Studies. Book review provided by the American Theological Library Association in 20168. The book reviewed is by Wertenbaker, Christian The Enneagram of G.I.Gurdjieff: Mathematics, Metaphysics, Music, and Meaning. Codhill Press, 2017

- ↑ The Traditional Enneagram. The Enneagram Institute. https://www.enneagraminstitute.com/the-traditional-enneagram/ Accessed on 4/3/24

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Wertenbaker, Christian The Enneagram of G.I.Gurdjieff: Mathematics, Metaphysics, Music, and Meaning. Codhill Press, 2017

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Oxford Academic Books. December 2019

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Oxford Academic Books. December 2019

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Oxford Academic Books. December 2019

- ↑ Cusack, Carole. The Contemporary Context of Gurdjieff’s Movements. University of Sydney. In: Religion and the Arts 21 (2017) 96-122

- ↑ Gurdjieff Halifax Organization. The Movements. https://www.gurdjieffhalifax.org/the-movements# Accessed on 4/11/24

- ↑ Panafieu, Bruno De; Needleman, Jacob; Baker, George (September 1997).

- ↑ Gurdjieff: Essays and Reflection on the Man and His Teachings. Continuum International Publishing Group. p 28. https://books.google.com/books?id=GV0dhZxB91EC&pg=PA28#v=onepage&q&f=false Accessed 3/29/24

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Music. The Gurdjieff/de Hartmann Piano Music and its Esoteric Significance. From Academia.eu. Membership required

- ↑ Jones, Constanze. California Institute of Integral Studies. Book review provided by the American Theological Library Association in 2016. The book reviewed is by Petsche Johanna: Gurdjieff and Music. The Gurdjieff/de Hartmann Piano Music and its Esoteric Significance.

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Music. The Gurdjieff/deHartmann Piano Music and its Esoteric Significance. Introduction. From Academia.eu. Membership required

- ↑ Gurdjieff, G.I. Meetings With Remarkable Men. New York: Penguin Compass, 2002 [1963], pp. 32 -50

- ↑ Gurdjieff, G.I. Meetings With Remarkable Men. New York: Penguin Compass, 2002 [1963], p. 148

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Music. The Gurdjieff/deHartmann Piano Music and its Esoteric Significance. Introduction. From Academia.eu. Membership required

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Lesson1

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel. Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1), June 2011. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 3/11/24

- ↑ Driscoll, Walter.An Indtroduction to the Writings of G.I.Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff International Review. https://www.gurdjieff.org/driscoll3.htm Accessed on 4/11/24

- ↑ de Salzmann, Jeanne. THE REALITY OF BEING: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff. Biographical Note. Shambhala, Boston & London, 2011

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel. Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1), June 2011. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 3/11/24

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel. Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1), June 2011. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 3/11/24

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel. Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1), June 2011. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 3/11/24

- ↑ Ginsburg, B. Seymor. Gurdjieff Unveiled: AN OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION TO GURDJIEFF'S TEACHING. Lighthouse Editions LTD; First Edition (January 1, 2005). Appendix

- ↑ de Hartmann, Olga. Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff. Cooper Square Publishers, Inc. New York, NY., 1964

- ↑ Gurdjieff International Review. Thomas de Hartmann. https://www.gurdjieff.org/hartmann.htm Accessed on 4/11/24

- ↑ Gurdjieff International Review. Olga de Hartmann https://www.gurdjieff.org/hartmann-o.htm Accessed on 4/11/24

- ↑ de Hartmann, Olga. Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff. Cooper Square Publishers, Inc. New York, NY., 1964

- ↑ Pogson, Beryl. Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait. Vincent Stuart Ltd,1961, p 2

- ↑ Pogson, Beryl. Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait. Vincent Stuart Ltd,1961, p 18

- ↑ Pogson, Beryl. Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait. Vincent Stuart Ltd,1961, p 71

- ↑ Pogson, Beryl. Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait. Vincent Stuart Ltd,1961, p. 94

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation. Maurice Nicoll. https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/mauricenicoll.htm Accessed on 4/13/24

- ↑ Maurice Nicoll. https://ggurdjieff.com/maurice-nicoll/ Accessed on 4/13/24

- ↑ Orage, A.R., Brück, Frank; Kherdian, David. Gurdjieff’s Emissary in New York: Talks and Lectures with A.R. Orage Book Studio, 2020, ISBN 9781914269059, Description of book.

- ↑ Webb, James. The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers. Hardcover, 1980, pp. 133-134

- ↑ Pentland, John. P. D. Ouspensky: Gurdjieff International Review, Winter 1998/1999. https://www.gurdjieff.org/pentland2.htm

- ↑ de Salzmann, Jeanne. The Reality of Being: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff. Biographical Notes. Shambhala, Boston & London, 2011.

- ↑ de Salzmann, Jeanne. The Reality of Being: The Fourth Way of Gurdjieff. Shambhala, Boston & London, 2011.

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Chapter: A Biographical Sketch. Oxford Academic Books. December 2019

- ↑ Azize, Joseph. The Changes in Gurdjieff’s Life. https://www.josephazize.com/2022/05/28/the-changes-in-gurdjieffs-life/ Accessed on 4/13/24

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation: The Teaching for Our Time. Gurdjieff’s Final Year. https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/70links/final_years.htm Accessed on 4/13/24

- ↑ Azize, Joseph et al. Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises. Oxford Academic Books. A Biographical Sketch. December 2019

- ↑ Azize, Joseph. Assessesing Borrowing. The Case of Gurdjieff. Aries – Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 20 (2020); 1-30

- ↑ Azize, Joseph. Assessesing Borrowing. The Case of Gurdjieff. Aries – Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 20 (2020); 1-30

- ↑ Horowitz, Mitch. G.I.Gurdjieff: A Short Introduction: The first principle of the search is understanding our degradation. Member-only story. 12/25/2023

- ↑ Kane, Paul. Work: Emerson, Wittgenstein, Gurdjieff In: SPIRITUS, Baltimore, Vol. 16. Issue 1

- ↑ Drury, Nevill. The New Age: The History of a Movement. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004; page 25

- ↑ Karalis, Vrasidas. Gurdjieff beyond the Personality Cult: Reading the Work and Its Re-Workings, Religion and the Arts 21 (2017) 176–188.