Johann Friedrich Zöllner: Difference between revisions

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:J. K. F. Zollner.jpg|right|200px|thumb|Professor Zöllner]] | |||

[[File:J. K. F. Zollner.jpg|right|200px]] | |||

'''Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner''' ([[November 8]], 1834, Berlin – [[April 25]], 1882, Leipzig) was a German astrophysicist who studied optical illusions. He was also an early psychical investigator. He was Professor of Physical Astronomy at the University of Leipzig; and a member of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences. | '''Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner''' ([[November 8]], 1834, Berlin – [[April 25]], 1882, Leipzig) was a German astrophysicist who studied optical illusions. He was also an early psychical investigator. He was Professor of Physical Astronomy at the University of Leipzig; and a member of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences. | ||

== Scientific work == | == Scientific work == | ||

[[File:Zollner illusion.png|left|150px]] | [[File:Zollner illusion.png|left|150px]] | ||

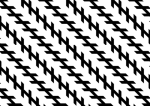

Prof. Zöllner discovered | Prof. Zöllner discovered an optical illusion that has become a classic, where a pattern surrounding parallel lines creates makes them appear as not parallel. This is known as the "Zöllner illusion." | ||

In 1872 he became a professor of astrophysics at the prestigious University of Leipzig. He proved the Doppler effect of motion of the color of stars. He made the first measurement of the Sun's apparent magnitude. There is a lunar crater named "Zöllner" in his honor. | |||

== Fourth dimension == | == Fourth dimension == | ||

Prof. Zöllner was interested in paranormal phenomena, and this interest was increased in 1875 by his acquaintance with scientist [[William Crookes]]. Eventually, he developed what he called "Transcendental Physics," which involved the study of [[ | Prof. Zöllner was interested in paranormal phenomena, and this interest was increased in 1875 by his acquaintance with scientist (and later, [[Theosophist]]) [[William Crookes]], who was interested in psychical research. Eventually, he developed what he called "Transcendental Physics," which involved the study of [[Phenomena#Spiritualistic phenomena|Spiritualistic phenomena]]. His intention was to take "miracles" out of the realm of religion and magic into that of science.<ref>Massimo Introvigne, "Zöllner’s Knot: Jean Delville (1867-1953), Theosophy, and the Fourth Dimension," Theosophical History XVII:3 (July, 2014), 85.</ref> | ||

Zöllner started experiments with American [[Spiritualism|Spiritualist]] [[Medium|mediums]], notably [[Henry Slade]], to test the theory of a fourth dimension of space. He attempted to demonstrate that the agencies acting in Spiritualist séances were four-dimensional entities. For this, he set up experiments with Slade which involved slate-writing, tying knots on string, recovering coins from sealed boxes and the interlinking of two wooden rings. He was successful in several of these experiments, although critics have suggested that the medium Henry Slade was a fraud who performed trickery in the experiments. | |||

His observations were published in his book '''''Transcendental Physics. An account of experimental Investigations''''', which was translated from German, with a Preface and Appendices, by [[Charles Carleton Massey]]. In 1881, [[Theosophical Society]] founder [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky|Mme. Blavatsky]] wrote that his book "should be in the library of everyone who pretends to hold intelligent opinions upon the subjects of Force, Matter, and Spirit."<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1995), 15.</ref> | |||

She added: | She added: | ||

<blockquote>He is also a profound metaphysician, the friend and compeer of the brightest contemporary intellects of Germany. He had long surmised that besides length, breadth, and thickness, there might be a fourth dimension of space, and that if this were so then that would imply another world of being, distinct from our three-dimensional world, with its own inhabitants fitted to its four-dimensional laws and conditions, as we are to ours of three dimensions.<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1995), 15.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>He is also a profound metaphysician, the friend and compeer of the brightest contemporary intellects of Germany. He had long surmised that besides length, breadth, and thickness, there might be a fourth dimension of space, and that if this were so then that would imply another world of being, distinct from our three-dimensional world, with its own inhabitants fitted to its four-dimensional laws and conditions, as we are to ours of three dimensions.<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1995), 15.</ref></blockquote> | ||

== Death == | |||

Zöllner’s interest in psychic matters brought him bitter opposition from various scientific quarters, and he was considered by some of his own former colleagues as merely a crank. The persecution to which he was subjected must have produced a considerable effect upon his general health.<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1997), 266.</ref> As Blavatsky wrote: | |||

<blockquote>Is the world of science aware of the real cause of Zöllner’s premature death? When the fourth dimension of space becomes a scientific reality like the fourth state of matter, he may have a statue raised to him by grateful posterity. But this will neither recall him to life, nor will it obliterate the days and months of mental agony that harassed the soul of this intuitional, farseeing, modest genius, made even after his death to receive the donkey’s kick of misrepresentation and to be publicly charged with lunacy.<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1997), 147.</ref></blockquote> | |||

He died suddenly of a stroke, seated at his desk, only 48 years of age. | |||

== Online resources == | |||

*[http://www.cesnur.org/2014/waco-introvigne-delville.pdf# Zöllner’s Knot: Jean Delville (1867-1953) Theosophy, and the Fourth Dimension] by Massimo Introvigne | |||

*[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Karl_Friedrich_Z%C3%B6llner# Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner] at Wikipedia | |||

*[http://www.katinkahesselink.net/blavatsky/articles/v3/y1881_004.htm# Transcendental Physics] by H. P. Blavatsky | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 25: | Line 38: | ||

[[Category:Scientists|Zollner, Johann]] | [[Category:Scientists|Zollner, Johann]] | ||

[[Category:Nationality German|Zollner, Johann]] | [[Category:Nationality German|Zollner, Johann]] | ||

[[Category:People|Zollner, Johann]] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:09, 17 May 2020

Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner (November 8, 1834, Berlin – April 25, 1882, Leipzig) was a German astrophysicist who studied optical illusions. He was also an early psychical investigator. He was Professor of Physical Astronomy at the University of Leipzig; and a member of the Royal Saxon Society of Sciences.

Scientific work

Prof. Zöllner discovered an optical illusion that has become a classic, where a pattern surrounding parallel lines creates makes them appear as not parallel. This is known as the "Zöllner illusion."

In 1872 he became a professor of astrophysics at the prestigious University of Leipzig. He proved the Doppler effect of motion of the color of stars. He made the first measurement of the Sun's apparent magnitude. There is a lunar crater named "Zöllner" in his honor.

Fourth dimension

Prof. Zöllner was interested in paranormal phenomena, and this interest was increased in 1875 by his acquaintance with scientist (and later, Theosophist) William Crookes, who was interested in psychical research. Eventually, he developed what he called "Transcendental Physics," which involved the study of Spiritualistic phenomena. His intention was to take "miracles" out of the realm of religion and magic into that of science.[1]

Zöllner started experiments with American Spiritualist mediums, notably Henry Slade, to test the theory of a fourth dimension of space. He attempted to demonstrate that the agencies acting in Spiritualist séances were four-dimensional entities. For this, he set up experiments with Slade which involved slate-writing, tying knots on string, recovering coins from sealed boxes and the interlinking of two wooden rings. He was successful in several of these experiments, although critics have suggested that the medium Henry Slade was a fraud who performed trickery in the experiments.

His observations were published in his book Transcendental Physics. An account of experimental Investigations, which was translated from German, with a Preface and Appendices, by Charles Carleton Massey. In 1881, Theosophical Society founder Mme. Blavatsky wrote that his book "should be in the library of everyone who pretends to hold intelligent opinions upon the subjects of Force, Matter, and Spirit."[2]

She added:

He is also a profound metaphysician, the friend and compeer of the brightest contemporary intellects of Germany. He had long surmised that besides length, breadth, and thickness, there might be a fourth dimension of space, and that if this were so then that would imply another world of being, distinct from our three-dimensional world, with its own inhabitants fitted to its four-dimensional laws and conditions, as we are to ours of three dimensions.[3]

Death

Zöllner’s interest in psychic matters brought him bitter opposition from various scientific quarters, and he was considered by some of his own former colleagues as merely a crank. The persecution to which he was subjected must have produced a considerable effect upon his general health.[4] As Blavatsky wrote:

Is the world of science aware of the real cause of Zöllner’s premature death? When the fourth dimension of space becomes a scientific reality like the fourth state of matter, he may have a statue raised to him by grateful posterity. But this will neither recall him to life, nor will it obliterate the days and months of mental agony that harassed the soul of this intuitional, farseeing, modest genius, made even after his death to receive the donkey’s kick of misrepresentation and to be publicly charged with lunacy.[5]

He died suddenly of a stroke, seated at his desk, only 48 years of age.

Online resources

- Zöllner’s Knot: Jean Delville (1867-1953) Theosophy, and the Fourth Dimension by Massimo Introvigne

- Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner at Wikipedia

- Transcendental Physics by H. P. Blavatsky

Notes

- ↑ Massimo Introvigne, "Zöllner’s Knot: Jean Delville (1867-1953), Theosophy, and the Fourth Dimension," Theosophical History XVII:3 (July, 2014), 85.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1995), 15.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1995), 15.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1997), 266.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1997), 147.