Portrait of the Yogi of Tiruvalla: Difference between revisions

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) |

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

In [[Mahatma Letter No. 92#Page 17|one of his letters]] to Mr. Sinnett, [[Koot Hoomi|Master K.H.]] praised Mme. Blavatsky's work as follows: | In [[Mahatma Letter No. 92#Page 17|one of his letters]] to Mr. Sinnett, [[Koot Hoomi|Master K.H.]] praised Mme. Blavatsky's work as follows: | ||

<blockquote>She can and did produce [[phenomena]], owing to her natural powers combined with several long years of regular training and her phenomena are sometimes better, more wonderful and far more perfect than those of some high, [[Initiation|initiated]] [[chela]]s, whom she surpasses in artistic taste and purely Western appreciation of art — as for instance in the instantaneous production of pictures: witness — her | <blockquote>She can and did produce [[phenomena]], owing to her natural powers combined with several long years of regular training and her phenomena are sometimes better, more wonderful and far more perfect than those of some high, [[Initiation|initiated]] [[chela]]s, whom she surpasses in artistic taste and purely Western appreciation of art — as for instance in the instantaneous production of pictures: witness — her portrait of the "fakir" Tiravalla mentioned in Hints, and compared with my portrait by [[Djual Khool|Gjual Khool]]. Notwithstanding all the superiority of his powers, as compared to hers; his youth as contrasted with her old age; and the undeniable and important advantage he possesses of having never brought his pure unalloyed magnetism in direct contact with the great impurity of your world and society — yet do what he may, he will never be able to produce such a picture, simply because he is unable to conceive it in his mind and Tibetan thought.<ref>Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., ''The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence'' No. 92 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), ???.</ref></blockquote> | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

Revision as of 16:47, 5 July 2013

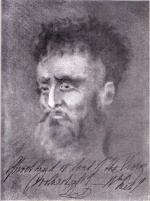

The Portrait of the Yogi of Tiruvalla is a painting phenomenally produced by H. P. Blavatsky for Col. Olcott and Mr. Judge in New York, in December 1877. However, just before they left for India, it disappeared from its frame in Olcott's bedroom. On August 23, 1879, while Blavatsky, Olcott, and Damodar were conversing in the office at Bombay, the portrait fell through the air on the desk at which Col. Olcott sat.[1]

Production

Mr. Sinnett described the production of the portrait as follows:

Colonel Olcott told me he took home a piece of note-paper from a club in New York- a piece bearing a club stamp -and gave this to Madame Blavatsky. She put it between the sheets of blotting-paper on her writing-table, rubbed her hand over the outside of the pad, and then in a few moments the marked paper was given back to him with a complete picture upon it representing an Indian fakir in a state of samadhi. And the artistic execution of this drawing was conceived by artists to whom Colonel Olcott afterwards showed it to be so good that they compared it to the works of old masters whom they specially adored and affirmed that as an artistic curiosity it was unique and priceless.[2]

Later, Col. Olcott commented on Mr. Sinnett's description and added some more details:

At the close of the dinner we had drifted into talk about precipitations, and Judge asked H. P. B. if she would not make somebody’s portrait for us. As we were moving towards the writing-room, she asked him whose portrait he wished made, and he chose that of this particular yogi, whom we knew by name as one held in great respect by the Masters. She crossed to my table, took a sheet of my crested club-paper, tore it in halves, kept the half which had no imprint, and laid it down on her own blotting-paper. She then scraped perhaps a grain of the plumbago of a Faber lead pencil on it, and then rubbed the surface for a minute or so with a circular motion of the palm of her right hand; after which she handed us the result. On the paper had come the desired portrait and, setting wholly aside the question of its phenomenal character, it is an artistic production of power and genius. Le Clear, the Noted American portrait painter, declared it unique, distinctly an “individual” in the technical sense; one that no living artist within his knowledge could have produced.[3]

In one of his letters to Mr. Sinnett, Master K.H. praised Mme. Blavatsky's work as follows:

She can and did produce phenomena, owing to her natural powers combined with several long years of regular training and her phenomena are sometimes better, more wonderful and far more perfect than those of some high, initiated chelas, whom she surpasses in artistic taste and purely Western appreciation of art — as for instance in the instantaneous production of pictures: witness — her portrait of the "fakir" Tiravalla mentioned in Hints, and compared with my portrait by Gjual Khool. Notwithstanding all the superiority of his powers, as compared to hers; his youth as contrasted with her old age; and the undeniable and important advantage he possesses of having never brought his pure unalloyed magnetism in direct contact with the great impurity of your world and society — yet do what he may, he will never be able to produce such a picture, simply because he is unable to conceive it in his mind and Tibetan thought.[4]

Description

The yogi is depicted in Samâdhi, the head drawn partly aside, the eyes profoundly introspective and dead to external things, the body seemingly that of an absent tenant. There is a beard and hair of moderate length, the latter drawn with such skill that one sees through the upstanding locks, as it were—an effect obtained in good photographs, but hard to imitate with pencil or crayon. The portrait is in a medium not easy to distinguish: it might be black crayon, without stumping, or black lead; but there is neither dust nor gloss on the surface to indicate which, nor any marks of the stump or the point used: hold the paper horizontally towards the light and you might fancy the pigment was below the surface, combined with the fibres.[5]

At the bottom of the painting there is an inscription that says “Ghostland or Land of the Living Brotherhood of T—Which?”

The beard in the painting was damaged by an Indian member who tried to test the quality of the artwork using an eraser. In recalling this event Col. Olcott wrote:

This incomparable picture was subjected in India later to the outrage of being rubbed with India—rubber to satisfy the curiosity of one of our Indian members, who had borrowed it as a special favour “to show his mother”, and who wished to see if the pigment was really on or under the surface! The effect of his vandal-like experiment is now seen in the obliteration of a part of the beard, and my sorrow over the disaster is not in the least mitigated by the knowledge that it was not due to malice but to ignorance and the spirit of childish curiosity.[6]

Subject

The yogi’s name was always pronounced by H. P.B. “Tiravâlâ”, but since coming to live in Madras Presidency, I can very well imagine that she meant Tiruvalluvar, and that the portrait, now hanging in the Picture Annex of the Adyar Library, is really that of the revered philosopher of ancient Mylapur, the friend and teacher of the poor Pariahs. As to the question whether he is still in the body or not I can venture no assertion, but from what H. P. B. used to say about him I always inferred that he was. And yet to all save Hindus that would seem incredible, since he is said to have written his immortal “Kural” something like a thousand years ago! He is classed in Southern India as one of the Siddhas, and like the other seventeen, is said to be still living in the Tirupati and Nilgiri Hills; keeping watch and ward over the Hindu religion. Themselves unseen, these Great Souls help, by their potent will-power, its friends and promoters and all lovers of mankind. May their benediction be with us!

In recalling the incident for the present narrative, I note the fact that no aura or spiritual glow is depicted around the yogi’s head, although H. P. B.’s account of him confirms that of his Indian admirers, that he was a person of the highest spirituality of aspiration and purest character.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves Second Series (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 214.

- ↑ Alfred Percy Sinnett, The Occult World (London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1969), ??.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves First Series (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 367-368.

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 92 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), ???.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves First Series (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 368.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves First Series (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 368-369.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves First Series (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 369-370.