Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (born October 19, 1433, in Figline, republic of Florence, Italy; died October 1, 1499, in Careggi, near Florence) was an Italian philosopher, theologian, doctor, musician and linguist whose translations and commentaries on the writings of Plato and other classical Greek authors generated the Florentine Platonist Renaissance that influenced European thought for over two centuries. [1]

The Renaissance was a time of major social, economic, and political upheaval and Ficino provided a stabilizing force for the society of Florence and played a significant role in influencing the thoughts and actions of the leaders of 15th century Europe. Ficino’s view of mankind and his interpretation of the immortality of the soul helped unleash extraordinary amounts of creativity in architecture, painting, sculpture and literature.

He also achieved the extremely difficult integration of Platonic reason with Christian religious doctrine and convinced leading thinkers that the human being was a reflection of the divine. [2]

Early Years

Ficino was born on October 19, 1433, in Figline Valdarno, a small community southeast of Florence, to his mother Alexandra (the daughter of a Florentine citizen) and her husband, Dietifeci Ficino. Dietifeci, a physician, eventually served early fifteenth-century Florence’s greatest patron, Cosimo de’ Medici, who by the time of Ficino’s birth was one of the richest men in Europe. While the precise details of his early life and education remain largely unclear [3] it can safely be said that he studied Scholastic philosophy and medicine at the University of Florence, and that he was exposed to the burgeoning educational movement of Italian Humanism. [4]

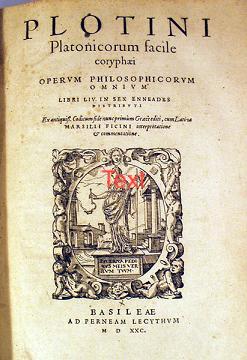

In 1438 Cosmo de' Medici made the acquaintance of Gemisthus Pletho, an ardent Platonist, who inspired him with the idea of founding a Platonic Academy in Florence. With this end in view, Cosmo selected Marsilio Ficino, and provided for his education in Greek philosophy. Ficino’s natural aptitude was so great that he was able to complete his first work on the Platonic Institutions when he was only twenty-three years old. At the age of thirty, after translating the Theogony of Hesiod, the Hymns of Proclus, Orpheus, and Homer, and all of the works of Hermes Trismegistus that could be found, Ficino began his translations of Plato. When that was finished, he turned to the Neoplatonic writers, and left behind him excellent translations of Plotinus, Iamblichus, Proclus and Synesius as his contribution to the work of the Theosophical Movement. [5]

Later Life

His entire career was marked by his wide-ranging conception of what it means to practice, rather than only to theorize about philosophy. This can be seen in his translations, letters, and philosophical treatises. Ficino’s initial activity, in the late 1450s, included short treatises, mostly epistolary, on certain basic philosophical matters. The 1460s saw him come into his own as a translator; these years also represent the beginnings of his work as a commentator and exegete. In 1464, when Cosimo de’ Medici was in the final stages of his life, Ficino read to him his new translations of certain Platonic dialogues. As that decade wore on Ficino authored commentaries on and summaries of Plato’s writings, many of which he continued to work on for the rest of his career. These included the Timaeus, Phaedrus, and the Philebus. Between 1469 and 1474 he composed his Theologia Platonica (Platonic Theology), which was published in 1482. [6]

Throughout his life Ficino carried on a steady correspondence with philosophers, poets, and politicians across Europe. This choice of philosophical expression shows the influence that Humanism had on him. In many letters, Ficino clarifies his understanding of certain Platonic concepts, such as poetic furor. In his letters he gave medical advice as well as practical counsel on how to cope with the deaths of loves ones and friends. He even discussed the astrological placement of planets that contribute to one’s character traits. [7]

Renewal and Spread of Platonism

A signal event was Ficino’s publication of the Complete Works of Plato (Platonis Opera Omnia), which included his translations of Plato’s writings, thirty-six in all. [8]

His interest was directed less to the linguistic form of the ancient works than to their philosophical content. His main concern was a contemporary renewal of ancient philosophy and Plato's teaching was the core, which he interpreted in the sense of the Neoplatonic tradition founded by Plotinus. With his striving for a consistent metaphysical worldview, in which theological and philosophical statements were to merge into an indissoluble unity, he joined the more strongly Christian current of humanism.

With this publication, students of Plato had access to the entire range of the dialogues, revealing the rich ancient landscape of myths, allegories, philosophical arguments, etymologies, fragments of poetry, other works of philosophy, aspects of ancient pagan religious practices, concepts of mathematics and natural philosophy. By and large, Renaissance readers in the Latin West encountered Plato's text through Ficino's translations and interpretation. [9]

As time went by, Ficino’s intellectual energies deepened his understanding of Platonism and shifted, in the late 1480s, to Plotinus, a project that included the first full Greek to Latin translation of Plotinus’s works along with commentary.

He considered himself a Platonist in a very specific mold: as part of a long tradition of which Plato was a key part but which needed interpreters to keep it going. This “ancient theology” included figures who, divinely inspired, advanced true philosophy. One of the key figures in this sequence was the ancient sage Hermes “Trismegistus”. For Ficino, as for the late ancient Platonists he admired, Hermes was an ancient Egyptian, roughly contemporary with Moses. [10]

Ficino believed that the ancient forms of thought are living traditions. He also inherited a late ancient habit of organizing the history of philosophy, religion, and thought in terms of spiritual succession. In his understanding, the historical transmission of knowledge requires actual persons to serve as spokespersons for the logoi connecting one generation to the next. [11]

The Platonic Academy of Florence

The precise nature of Florence’s Academy remains unclear today. [12] However, while extant sources do not permit to categorize the Platonic Academy as a formal school or advanced institution with regular meetings, there are some facts that can be documented: In 1463 Cosimo de Medici gave Ficino a small property in Careggi with a domicile [13] where Ficino brought together the greatest thinkers, artists and leaders of Florence and helped them shape, build and bring into reality in their own field his fundamental ideals. Thus, the Academy was most likely a spiritual community bound together by a common bond of love to each other and to Ficino. [14]And even though the group was never formally organized, its members considered themselves a re-creation of the Academy hat had been formed by Plato in Athens. [15]

Philosophical Themes

The Integration of the Platonic Ideals with Christian Belief

Ficino feared that his contemporaries were losing their way because of their tendency to separate philosophy from religion. He considered the Platonic corpus a treasury of wisdom, filled with different subject matters but always, when rightly interpreted, leading one to the divine. [16] He showed that Plato’s ideas of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful were evidence of the love of one absolute and all-pervading God. For him, Christianity must rest on philosophical grounds and he argued that Plato does not stop at intermediate causes but rises to the highest cause. His writings led to the adoption of the belief in the immortality of the soul as a central Christian tenet. Ficino brought Platonic ideas into Christianity and merged Christianity with Reason.[17]

God is immanent and the Soul Divine

The immortality and divinity of the human soul represented Ficino’s main preoccupation, because he feared the potential loss of belief among intellectual elites. [18]

In 1473 he began to publish his ideas which emphasized the divinity of Man’s soul and the personal relationship between Man and God. He wrote:

“Let him revere himself as an image of the Divine of God. Let him hope to ascend again to God, as soon as the Divine Majesty deigns in some way to descend to him. Let him love God with all his heart, so as to transform himself into Him, who through singular love wonderfully transformed Himself into Man.”[19]

Ficino searched to find forces binding human beings to one another and for him love linked all things together. Love flowed first from God into all existing things, permeating everything. [20]

Legacy

Marsilio Ficino was a priest, a doctor, and one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as a practicing astrologer and magician whose daunting life’s work was to reconcile religious faith with philosophical reason. [21] He perceived himself as continuing a lineage of astrologer-priests from ancient and pagan times and philolosophical theology and astrology were closely linked in his mind. [22] He was known for his love of music and inherited the medieval tradition of linking astrology, music, and medicine into a holistic view of health. [23]

He was ordained in 1473 and later became a canon of Santa Maria del Fiore, a cathedral in Florence. Despite being ordained, he faced opposition and censure from the Church on account of his Platonic teachings. Ficino’s acceptance by the church was further strained as a result of his association with the brilliant scholar Pico della Mirandola. [24] Due to his study of medicine, he was interested in his own and his friends’ health. He was given credit for remarkable cures for many of his friends and provided his service free of charge. In 1478 there was an outbreak of plague in Florence and Ficino helped overcome the disease by publishing a practical guide to the treatment of plague. This was made immediately accessible and of use to citizens and was later translated into Latin as a standard medical text. Ficino was a unique type of philosopher with powerful intellectual and spiritual ideas and immensely practical. He brought spirituality into the heart by making it part of the total environment and culture of society. He brought about cultural change by continually encouraging leaders to maintain their health in body and mind, to keep good company, and to live and work in an environment that was harmonious and uplifting. He also insisted that leaders become examples of the highest qualities and only focus on activities and actions that bring out the best in human nature. [25]

Ficino died in 1499, leaving a significant cultural legacy. His Latin translations of Plato, Plotinus, and other Platonizing thinkers became standard ones for over three centuries after his death and his theories on love permeated sixteenth-century literature. [26] His life and work made a significant contribution to the ideas, science, and art of the Renaissance in several important ways. 1. He integrated the Greek’s use of reason and Platonic ideals with Christian belief. 2. He rekindled the idea that God was immanent, permeated all things and that the human soul was an expression of God. 3. The establishment of an Academy that brought ideas from all around the world to discuss, debate and to seek universal truth. 4. He influenced leaders’ need to live and represent Spirit in everything they did and to create a society that was just, fair, and uplifting for the human spirit. [27]

Notes

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino, Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marsilio-Ficino, Accessed on 4/4/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadeership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/ficino/ Accessed on 3/28/23

- ↑ The Neoplatonic Revival. GREAT THEOSOPHISTS THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 4, February, 1938. https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/revival.html. Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/ficino/ Accessed on 3/28/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Robichaud, Denis J.J. Plato’s Persona: Marsilio Ficino, Renaissance Humanism, and Platonic Traditions. 2018. University of Pennsylvania Press

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Robichaud, Denis J.J. Plato’s Persona: Marsilio Ficino, Renaissance Humanism, and Platonic Traditions. 2018. University of Pennsylvania Press

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/ficino/ Accessed on 3/28/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadeership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Platonic Academy. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Platonic-Academy. Accessed on 4/6/22

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadeership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/1/23

- ↑ Voss, Angela. Marsilio Ficino. Western Esoteric Master Series. 2006. North Atlantic Books

- ↑ Clydesdale, Rugh. Jupiter Tames Saturn: Astrology in Ficino’s Epistolae. In: Laus Platocini Philosophi. Marsilio Ficino and his Influence. Brill. 2011

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Ficino, Marsilio. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/ Accessed on 4/5/23

- ↑ Cacioppe, Ron. Marsilio Ficino: Magnus of the Renaissance, Shaper of Leaders. Integral Leadership Review. http://integralleadershipreview.com/5397-feature-article-marsilio-ficino-magnus-of-the-renaissance-shaper-of-leaders/ Accessed on 4/5/23