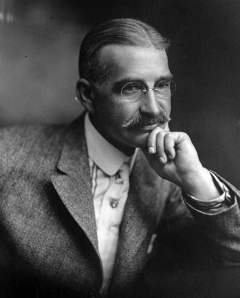

L. Frank Baum

Lyman Frank Baum (May 15, 1856 – May 6, 1919) was an American author of children's books, best known for writing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. He and his wife Maud were members of the Theosophical Society.

Early life

L. Frank Baum was born May 15, 1856 in Chittenango, Oneida County, New York to Benjamin Ward Baum and his wife Cynthia Ann Stanton Baum. Benjamin was a wealthy merchant banker in 1870, and succeeded in other businesses as diverse as oil drilling, barrel making, and real estate. By 1880 the family had a farm in Onondaga County, New York, raising fancy poultry.[1] The boy Frank had a printing press, and published The Rose Lawn Home Journal, named after the family estate. He left home at seventeen and experimented with various occupations such as journalism and acting in stock companies. At the age of 25, he wrote a play, "The Maid of Arran," and produced and directed it in New York.

Marriage and family

The next year on November 9, 1882 he married Maud Gage (March 27, 1861 - March 6, 1953). The couple moved around - South Dakota, Illinois, Iowa - and Baum supported his growing family as best he could. He manufactured axle grease; ran a variety store; edited the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer; sold glass and china; and wrote books. By 1900 they had five children and were living in Fairview, Iowa.[2] His son Harry wrote,

He had a touch of genius. Perhaps more important than that he filled our house with love.

He was never stern. There was always laughter in the house. Father was a kindly man, loved people, never swore or told a dirty story. He had no business sense and made many poor investments. But we always had necessities and even luxuries.[3]

Theosophical Society involvement

Matilda Joslyn Gage, Baum's mother-in-law, was an ardent Theosophist, having been admitted to the Rochester Theosophical Society on March 26, 1885 by Josephine Cables. He and his wife Mrs. Maud G. Baum joined Chicago's Ramayana branch of the Theosophical Society on September 4, 1892 upon the recommendation of Dr. W. P. Phelon and M. M. Phelon.[4][5]

In the first issue of the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer in 1890 under his editorship (before he joined the Society), he wrote about Theosophy saying:

Amongst the various sects so numerous in America today who find their fundamental basis in occultism, the Theosophist[s] stand pre-eminent both in intelligence and point of numbers.

The recent erection of their new temple in New York City has called forth the curiosity of the many,the uneasiness of the few. Theosophy is not a religion. Its followers are simply “searchers after Truth.” Not for the ignorant are the tenets they hold, neither for the worldly in any sense. Enrolled within their ranks are some of the grandest intellects of the Eastern and Western worlds.

Purity in all things, even to asceticism is absolutely required to fit them to enter the avenues of knowledge, and the only inducement they offer to neophytes is the privilege of “searching for the Truth” in their company.

As interpreted by themselves they accept the teachings of Christ, Budda [sic], and Mohammed, acknowledging them Masters or Mahatmas, true prophets each in his generation, and well versed in the secrets of nature. But the truth so earnestly sought is not yet found in its entirety, or if it be, is known only to the privileged few.

The Theosophists, in fact, are the dissatisfied of the world, the dissenters from all creeds. They owe their origin to the wise men of India, and are numerous, not only in the far famed mystic East, but in England, France, Germany and Russia. They admit the existence of a God--not necessarily a personal God. To them God is Nature and Nature God.

We have mentioned their high morality: they are also quiet and unobtrusive, seeking no notoriety, yet daily growing so numerous that even in America they may be counted by thousands. But, despite this, if Christianity is Truth, as our education has taught us to believe, there can be no menace to it in Theosophy.[6]

Biographer Michael Patrick Hearn wrote,

His son Frank admitted the author’s interest in Theosophy, but also reported that the elder Baum could not accept all its teachings. He firmly believed in reincarnation; he had faith in the immortality of the soul and believed that he and his wife had been together in many past states and would be together in future reincarnations, but he did not accept the possibility of the transmigration of souls from human beings to animals or vice versa, as in Hinduism. He was in agreement with the Theosophical belief that man on Earth was only one step on a great ladder that passed through many states of consciousness, through many universes, to a final state of Enlightenment. He did believe in Karma, that whatever good or evil one does in his lifetime returns to him as reward or punishment in future reincarnations.... He believed that all the great religious teachers of history had found their inspiration from the same source, a common Creator.[7]

Wizard of Oz books

According to an Associate Press story in 1961, Baum visited Chicago publisher George M. Hill in 1900 with the manuscript of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and told how it came to be written:

I was sitting on a hatrack in the hall, telling the kids a story and suddenly this one moved right in and took possession. I shooed the children away and grabbed a piece of writing paper that was lying there on the rack and began to write.

It really seemed to write itself. Then I couldn't find any regular paper, so I took anything at nil, even a bunch of old envelopes. Had to have something.[8]

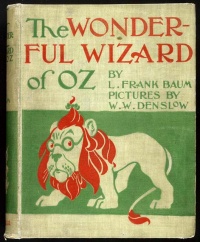

Hill published the first volume in Chicago on May 17, 1900. Illustrations by Baum's friend W. W. Denslow added greatly to the appeal of the book. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and its thirteen sequels have been reprinted many times, selling millions of copies. The first novel was adapted as a popular 1902 musical at the Chicago Grand Opera and on Broadway in New York. In 1939 the musical film version called The Wizard of Oz was released to great acclaim. The Oz works continue to be enormously popular.

In 1905 Baum bought Pedloe Island with the idea of establishing an amusement park for children, "Ozland," but never completed the project. Later Disneyland created an Emerald City.[9]

The Oz books are filled with concepts that are recognizable to Theosophists, such as self-transformation and alternate realities.

Later years

By 1910 the Baums had moved to Los Angeles, California. Mr. Baum died on May 6, 1919 in Los Angeles, California, and Maud survived him until March 6, 1953.

Writings

The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer was published by L. Frank Baum from January 25, 1890 - March 21, 1891,[10] and he worked as a reporter for other papers. In the Pioneer he wrote about occult fiction such as that by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, H. Rider Haggard, and Mabel Collins, and also about topics of interest to spiritualists and Theosophists - mediumship and elementals.

Baum wrote at least 73 books. He used pseudonyms for 36 of them - Captain Hugh Fitzgerald, Floyd Akers, Edith van Dyne, Suzanne Metcalr, Laura Bancroft, John Estes Cooke, and Schuyler Stanton. "Of the 37 in his own name, 14 were about Oz."[11].

See also

Other resources

Articles

- A Notable Theosophist: L. Frank Baum by John Algeo

- Oz and Kansas: A Theosophical Quest by John Algeo

- Theosophical Wizard of Oz by John Algeo

- The Wizard of Oz: The Perilous Journey by John Algeo

- The Wizard of Oz on Theosophy by L. Frank Baum

- The Spirituality of Oz: The Meaning of the Movie by Andrew Johnson

- The Oz books and Theosophy by Robert O'Connor

- The Theosophical foundations of L. Frank Baum's Wizard of Oz by Wayne Purdin

- The Occult Roots of The Wizard of Oz at The Vigilant Citizen

- Dorothy Gage and Dorothy Gale by Sally Roesch Wagner

Audio

- A Myth for Our Lives: Follow the Yellow Brick Road by John Algeo

Archival Collections

- L. Frank Baum Papers at Syracuse University Libraries.

- L. Frank Baum collection at Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Notes

- ↑ U.S. Census records for 1870, 1880.

- ↑ U. S. Census 1900.

- ↑ Associated Press story. Binghamton Press. April 1, 1961.

- ↑ Per John Algeo: This information was kindly supplied by Grace F. Knoche and Kirby Van Mater, of the Theosophical Society headquartered in Pasadena, California. The Baums’ membership is recorded on Register 1, page 561, and Matilda Gage’s on the same Register, page 49.

- ↑ Membership dates for the Baums are confirmed by the Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entries 8508 and 8509 (website file: 1C/65).

- ↑ A Notable Theosophist: L. Frank Baum by John Algeo

- ↑ Michael Patrick Hearn, ed.,The Annotated Wizard of Oz (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1973), 72-73.

- ↑ Associated Press story. Binghamton Press. April 1, 1961.

- ↑ Associated Press story. Binghamton Press. April 1, 1961.

- ↑ Microfilm of this periodical is available in the John Algeo Papers, Records Series 8.12, Theosophical Society in America Archives, Wheaton, Illinois.

- ↑ Associated Press story. Binghamton Press. April 1, 1961.