Burton Callicott

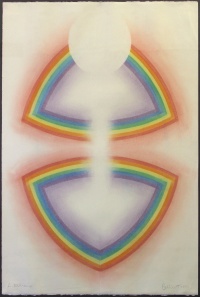

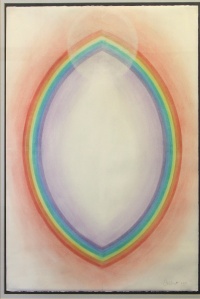

Burton Harry Callicott was an art professor from Memphis, Tennessee who incorporated Theosophical concepts into his paintings and drawings. His work has been described as "the relationship between nature and the human spirit, epitomized in the effects of light."[1] Three of his paintings were donated by the artist and his family for the collection of the Theosophical Society in America: Antahkarana, Mandorla, and Mandorla #12. Late in life he also expressed himself in poetry:[2]

- My wall daily graced

- With ovals and circles

- born of the marriage

- of leaf and sun.

Personal life

Burton Callicott and his fraternal twin brother William were born December 28, 1907 in Terre Haute, Indiana. When he was four years old, his family moved to Memphis. After graduation from the Cleveland School of Art in 1931, he returned to Memphis to teach in public schools. Like many Depression-era artists, he found temporary employment within a federal agency. The Federal Public Works of Art Program commissioned him to paint murals for the stairway of the Pink Palace Museum. The exploration of the Mississippi River by Hernando de Soto was the subject of the murals.[3][4]

During this period, Callicott began working with his stepfather Michael Abt in the design of floats for the Memphis Cotton Carnival and Christmas parades. They shared this activity for 20 years beginning in 1932.

Evelyne Baird married Burton Callicott in 1932, and they spent more than 60 years together. The couple had two children. Their small house in Memphis had an artist's studio with north-facing skylight and rainbows hanging in the window.[5]

The Callicotts joined the First Unitarian Church of Memphis, "a big tent for diverse beliefs," and in 1965 to the Church of the River. Reverend Burton Carley became a friend.[6]

Involvement with Theosophy

Late in the 1950s, Callicott developed an interest in Theosophy. After joining the Theosophical Society in America in 1959, he became a life member.[7] For many years he participated in the Memphis Lodge activities as President and in other capacities. In addition to leading classes in Theosophy, he lectured on many topics such as "Karma", "An Introduction to Hinduism," "The Hidden Wisdom of Masterworks," "Intuition in Art," "Life after Death," and "The Development of the Buddhi." In 1981 he was a guest speaker at the Ozark Theosophical Camp for the Midwest Theosophical Federation. He also wrote articles for Theosophical periodicals, including "Mandorlas, Halos and Rings of Fire," an analysis of Caravaggio's painting The Calling of St. Matthew, and an analysis of Dürer's Knight, Death, and the Devil.

He considered himself to be mystically inclined, but not a mystic.[8] He left a notebook for his daughter in which he inscribed these words by Burton Carley:

Spirituality is about a whole life, the important tasks that are necessary for our inner growth, in different stages. it is not something that one can get right once and for all. It is an evolution and not a finished product.[9]

Career

Callicott's art career demonstrated great flexibility of mind and imagination, as it ranged from painting murals and carnival floats to wartime drafting to teaching and calligraphy. He wrote of art:

Art reaches layers of consciousness that are inaccessible to verbal formulations and rational discourse. I believe that works of art actually emanate energies which have the power of resonating with and drawing responses at spiritual levels.[10]

Pink Palace Museum murals

During the Great Depression, like many of his contemporary artists, Callicott found temporary employment within a federal agency. The Federal Public Works of Art Program commissioned him to paint murals for the stairway of the Pink Palace Museum. The exploration of the Mississippi River by Hernando de Soto was the subject of the murals.[11][12]

Later in his life, the artist reflected on the murals in the Pink Palace Museum that he had painted during the Great Depression:

Looking back on the three mural panels I painted in 1934 on the north wall of the lobby of the Pink Palace Museum in Memphis, can we not now see larger meanings in the expanded context of the history of the North American continent? Could not the central panel, The Coming of Desoto (the first designed and executed), symbolize the profoundly transforming invasion of the continent by the white man; and the panel on the left, Conflict with the Indians (the second one painted) symbolize the eventual defeat and domination of the aboriginal population by the invading Europeans; and the panel on the right The Discovery of the Mississippi River (the final one painted), symbolize the eventual exploration and settlement of the vast West by the burgeoning white population?[13]

According to the museum website,

The museum’s advisory board [in1934] wanted the option of removing the paintings if they did not like them, so Callicott painted the three scenes on canvas instead of directly to the wall. The murals hung until 1995 when they were removed for extensive conservation. After the restoration, the conservators returned the murals to the museum rolled, and staff restretched the canvases and added frames on the floor of the lobby before rehanging them.[14]

In 2016 the museum moved the murals into storage as a preparation for new exhibits.

World War II drafting

Military service was compulsory after 1941, and Callicott contributed to the national war effort in World War II by working as a draftsman.

In 1945, he worked as a draftsman... providing "exploded drawings" for a pressurized-gunner's cabin subassembly for B-29 bombers, manufactured by the McDonnald [sic] Aidcraft Corportation located at the Memphis Municipal Airport. The drawings helped the workers on the plant floor put the nuts bolts, and other parts together correctly."[15]

Artistic style

Early in his career, Callicott painted naturalistic landscapes. He explored many media in his works, using charcoal, pastel, dry color pigments, oils, and glazes. Light contrasted with shadows, and light refracted into rainbows are frequent components of Callicott's art. He prepared his own canvases, acetate stencils, and frames. His technique often involved many layers of translucent glazes, and he often had to restretch his canvas repeatedly. The complexity of his work and his teaching commitments limited the number of works completed. He wrote:

My paintings, always inspired by light, (aside from the early figurative works); at first direct sunlight on trees, green fields, roads, houses, sunset and moonlit skies – finally became in the eighties and nineties attempts to paint light itself. Those paintings evolved from paintings of the rainbow done in the seventies. The phenomenon of the prismatic colors emerging from white light seemed to me to bear a correspondence to the universally held belief that the numberless forms of life in nature emanate from the One Creative Source. Awareness of this correspondence led to a number of paintings – in various designs – all in prismatic colors, appearing to emerge from empty white areas. I refer to them as symbolic abstractions.[16]

Teaching career

Callicott taught at the Memphis College of Art from 1937 to 1973, and then retained emeritus status until his death. According to a colleague, he was a well loved professor, with an open door and a gentle, receptive attitude toward students.[17]

Exhibitions

The Memphis Academy of Art, now the Memphis College of Art, exhibited Callicott's work in 1971. The artist had many exhibitions in Memphis and throughout the South.

In 1991, the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art held a retrospective exhibition of the artist's work, curated by Patricia P. Bladon. Callicott was then 83 years old. About forty works were exhibited and a beautiful exhibition catalog was issued. The cover shows a fragment of Callicott's 1980 work, Moonrise Over Nauset Beach, which is executed in oil on canvas.

Later years

Mr. Callicott died on November 23, 2003.

Additional resources

- Art & Soul. 2020. A collection of poems and paintings by Burton Callicott, and prayers and meditations by Burton Carley. Edited by J. Baird Callicott.

- "Burton Callicott (1907-2003)" by Elizabeth H. Moore. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, Version 2.0. This biographical sketch of the artist is available at this site.

- Callicott's papers are in the Smithsonian Institution. See also Archives of American Art.

- Slides of his works are available in the Smithsonian collection, and also at the Memphis College of Art.

- A 30-minute video portrait of the artist called "Journeyman of Light" was created for the Memphis Art Gallery Association in 1991. It was produced by Jim Crosthwait to accompany an exhbition at the Memphis Brooks Museum of 73 pieces of art.

- An online gallery of art works has been posted by Memphis Tech High School.

- Burton Callicott and Veda Reed: Teacher and Student is a catalog of and exhibition held March 28 - April 27, 1996 at Tobey Gallery, Memphis College of Art.

Notes

- ↑ Fredric Koeppel, "A Life on Canvas:Callicott Reflects on Limitless Art Career," Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 24, 1991.

- ↑ Burton Callicott, "5" Art & Soul (2020), 12.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "History of the Mansion" at Memphis Museums website.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ J. Baird Callicott, "Foreword" Art & Soul (2020), x.

- ↑ Membership database and microfilm records. Theosophical Society in America Archives. Callicott's member ID number was 010810.

- ↑ Fredric Koeppel, "A Life on Canvas: Callicott Reflects on Limitless Art Career," Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 24, 1991.

- ↑ Excerpt from Burton Callicott's notes in "Alice's book" reproduced in Foreword to Art & Soul (2020), xii.

- ↑ Excerpt from Burton Callicott's notes in "Alice's book" reproduced in Foreword to Art & Soul (2020), xiv.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "History of the Mansion" at Memphis Museums website.

- ↑ Excerpt from Burton Callicott's notes in "Baird's book" reproduced in Foreword to Art & Soul (2020), viii.

- ↑ Caroline Mitchell Carrico, "Mural Move at the Pink Palace" 14 December 2016 blog posting.

- ↑ J. Baird Callicott, "Foreword" Art & Soul (2020), x.

- ↑ Excerpt from Burton Callicott's diary entry reproduced in Foreword to Art & Soul (2020), xvi.

- ↑ Linda Disney, interview by Janet Kerschner, 2007. Theosophical Society in America Archives.