Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (1214 or 1220 – 1292) was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar. He has been called the "first scientist," because he pioneered the empirical method of observing, forming hypotheses and testing the hypotheses according to scientific principles during the thirteenth century. He thus broke with the tradition of using ancient authorities as "scientific" proof. Until the late seventeenth century, it was still common practice to defer to tradition rather than to test ideas. [1]

He also wrote on alchemy, magic and astrology. Roger Bacon was posthumously awarded with the title "Doctor Mirabilis" ("wonderful teacher").

There are diverging evaluations of Roger Bacon’s “experimental” knowledge. The research is continuing and SISMEL at Florence, Italy now houses a Roger Bacon research center. It has plans for future critical editions. A new international society for the study of Roger Bacon, The Roger Bacon Research Society has recently been established. [2]

Early Years

Very little is known about Bacon's life, and almost all is based on his own writings. To calculate the year of his birth, scholars have worked back from his "Opus tertium," of 1267. In this book, he mentions the length of time he has studied. If he meant his university education, since most boys went to Oxford or the University of Paris at the age of thirteen, this would make 1214 his birth year. However, if Bacon was referring to his primary education, the year 1220 would be more reasonable as the year of his birth. [3]

Bacon was the younger son of a wealthy landed family; he was well-versed in the classics and enjoyed the advantages of an early training in geometry, arithmetic, music, and astronomy. [4]

Although his family had lost its fortune, Bacon's father was able to send him to Oxford University. At that time, students wishing to enter the university had to take minor orders in the Catholic Church and were subject to church law and discipline. [5] Bacon received his master's degree in 1233. At that time, the degree was equivalent to ordination. The next year, Bacon continued his studies at the University of Paris, where he received another master's degree, and then remained at the school as a lecturer. In 1250, Bacon returned to lecture at Oxford. His renown spread quickly because of his obvious ability. It is believed that Bacon became a Franciscan friar about the same time as his return to Oxford. He would go on to become one of the most famous members of the order. [6]

Science and Theology

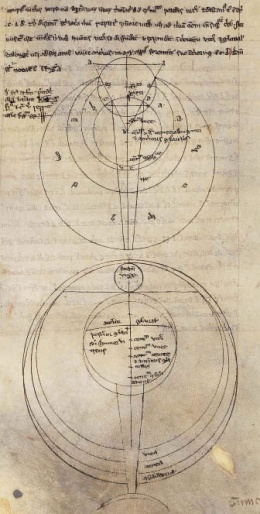

In the earlier part of his career, Bacon lectured in the faculty of arts on Aristotelian and pseudo-Aristotelian treatises, displaying no indication of his later preoccupation with science. About 1247 a considerable change took place in Bacon’s intellectual development. From that date forward he expended much time and energy and huge sums of money in experimental research, in acquiring “secret” books, in the construction of instruments and of tables, in the training of assistants, and in seeking the friendship of savants—activities that marked a definite departure from the usual routine of the faculty of arts. From 1247 to 1257 Bacon devoted himself wholeheartedly to the cultivation of those new branches of learning to which he was introduced at Oxford—languages, optics, and alchemy—and to further studies in astronomy and mathematics. He was the first European to describe in detail the process of making gunpowder, and he proposed flying machines and motorized ships and carriages. Bacon displayed a prodigious energy and zeal in the pursuit of experimental science and therefore represents a historically precocious expression of the empirical spirit of experimental science. [7]

Theosophical view

According to Mme. Blavatsky he was an "Adept-Initiate"[8]. She also wrote:

Roger Bacon, the friar, was laughed at as a quack, and is now generally numbered among "pretenders" to magic art; but his discoveries were nevertheless accepted and are now used by those who ridicule him the most. Roger Bacon belonged by right if not by fact to that Brotherhood which includes all those who study the occult sciences. . . . His discoveries — such as gunpowder and optical glasses, and his mechanical achievements — were considered by every one as so many miracles. He was accused of having made a compact with the Evil One. [9]

The Knowledge of Roger Bacon did not come to this wonderful old magician by inspiration, but because he studied ancient works on magic and alchemy, having a key to the real meaning of words. [10]

Last Years

Bacon had frequently complained that the sciences were neglected by theologians and other scholars. He attacked the ignorance and vices of clerics in his vitriolic "Compendium studii philosophiae" ("Compendium of Philosophical Studies") in 1271-1272. In 1277, Jerome d'Ascoli, the minister general of the Franciscan Order, condemned Bacon for his work, including his attacks on other theologians. Bacon, along with several other friars, was sentenced to imprisonment. In 1288, d'Ascoli became Pope Nicholas IV. His replacement as minister-general, Raymond of Gaufredi, ordered the release of the Ancona prisoners. Upon his release from prison, Bacon returned to Oxford. In 1292, he produced "Compendium studii theologiae" ("Compendium of Theological Studies"). [11]The exact date of Roger Bacon’s death is not known but it took place in Oxford in 1292. [12]

Assessment

The reception of the life and works of Roger Bacon is complex. Each generation has, as it were, found its own Roger Bacon. One study has provided a thoughtful account of the complex reception of Roger Bacon in England and of the extent to which the image of the Doctor Mirabilis is often colored by the changing controversies of the present down through history. [13]

Roger Bacon was an important teacher of the Arts at Paris in the 1240s. He was ahead of his time in the vigorous way he integrated the new Aristotle with the traditional Latin traditions of grammar and logic. He taught for a long period in the Arts.

By 1248–49 he seems to have become an independent scholar. He then returned to England, where he was attracted to language study including the learning of ancient languages, experimental concerns such as optics and experimental science, and a renewed critical study of the text of Scripture. When Bacon returned to Paris in the 1250s, he was to oppose what had become a profound change in the methodology of university learning, that is, the introduction of the “Sentence-Method” into the study of theology. On the instruction of Pope Clement IV, Bacon wrote in 1266 in a very short time the Opus maius, and the related works, Opus minus and Opus tertium in which he set out his own new model for a reform of the system of philosophical, scientific, and theological studies, seeking to incorporate language studies and science studies, then unavailable, at the University of Paris. The later Roger Bacon had a good knowledge of the geography and history of the world and an awareness of geo-politics, and he set out themes in his philosophy of language, philosophy of nature, and moral philosophy and theology that would influence fourteenth century writers. He is much more important for the philosophy of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries than has hitherto been recognized. As noted in the introduction, the newly formed Roger Bacon Research Society will soon do much to further the study of the scientific, philosophical, and theological works of Roger Bacon. [14]

The versatility of Roger Bacon appears in the fact that he was a philosopher, mathematician, philologist, physical geographer, chemist, and physician, earning for himself the title of "Doctor Mirabilis." He was also hailed as the peer of Avicenna and Averroes, as well as Aristotle, the industrious pupil of Plato.[15]

He was a great astronomer and rectified the Julian calendar. He was an expert in the science of optics, analyzing the property of lenses and convex glasses, inventing spectacles, telescopes, and microscopes. One of his cipher manuscripts shows that he was familiar with micro-organisms, with the cellular structure of plants and with bacteria. In this manuscript many of the discoveries attributed to Pasteur and Lister are carefully outlined.

The predictions made by Roger Bacon are quite as astonishing as his discoveries. He anticipated the invention of the hydraulic press, the diving bell, and the kaleidoscope, which he declared were all known to the ancients and would be known again in the future.

He foretold the time when ships would cross the ocean without the aid of rowers, propelled under the direction of a single man, and said:

It is equally possible to construct cars which may be set in motion with marvelous rapidity, independently of horses or other animals. Flying machines may also be made, the man seated in the center, and by means of artificial contrivances beating the air with artificial wings. [16]

Roger Bacon, anticipating the imaginative mechanisms of Leonardo da Vinci and the philosophy of human dignity of Pico della Mirandola, held high the torch that would ignite the bright creative fire of the Renaissance. Freeing the mind from religious dogma, pointing to the essential unity of man and Nature, showing how the human mind could cooperate with the intelligent hierarchies of the physical and spiritual worlds, he proclaimed the necessity of self-conscious evolution towards divine enlightenment and the possibility of creating a paradise on earth. [17]

Online resources

Articles

- Roger Bacon at Theosophy Trust website

- Roger Bacon at WisdomWorld.org

Books

Notes

- ↑ Bailey, Ellen. Roger Bacon 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=676deb00-0146-47a2-b1ed-a4f653d88cb5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=20916045&db=ulh. Accessed on 3/17/22 – Membership required

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Roger Bacon 2007-2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/roger-bacon Accessed on 3/17/22

- ↑ Bailey, Ellen. Roger Bacon 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=676deb00-0146-47a2-b1ed-a4f653d88cb5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=20916045&db=ulh. Accessed on 3/17/22 – Membership required

- ↑ Britannica. Roger Bacon https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-Bacon Accessed on 3/17/22

- ↑ Bailey, Ellen. Roger Bacon 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=676deb00-0146-47a2-b1ed-a4f653d88cb5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=20916045&db=ulh. Accessed on 3/17/22 – Membership required

- ↑ Bailey, Ellen. Roger Bacon 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=676deb00-0146-47a2-b1ed-a4f653d88cb5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=20916045&db=ulh. Accessed on 3/17/22 – Membership required

- ↑ Britannica. Roger Bacon https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-Bacon Accessed on 3/17/22

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. XI (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973), 546.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled vol. I, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 64-65.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine vol. I, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 581-582.

- ↑ Bailey, Ellen. Roger Bacon 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra - School Edition. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=676deb00-0146-47a2-b1ed-a4f653d88cb5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=20916045&db=ulh. Accessed on 3/17/22 – Membership required

- ↑ Westacott, E. Roger Bacon. Philosophical Library, 1955, page 26. https://archive.org/details/rogerbacon032106mbp/page/n31/mode/2up Accessed on 3/17/86

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Roger Bacon 2007-2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/roger-bacon Accessed on 3/20/22

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Roger Bacon 2007-2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/roger-bacon Accessed on 3/17/22

- ↑ Theosophy Trust. Roger Bacon https://theosophytrust.org/329-roger-bacon# Accessed on 3/17/22

- ↑ Great Theosophists. </>Roger Bacon</> Theosophy, Vo. 26, No, 2, December 1937; https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/rogerbacon.html Accessed on 3/18/22

- ↑ Theosophy Trust. Roger Bacon https://theosophytrust.org/329-roger-bacon# Accessed on 3/20/22