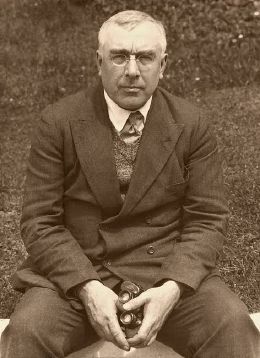

P. D. Ouspensky

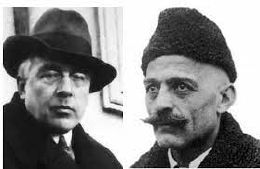

Petyr Dem’ianovich Uspenskii (March 5, 1878 – October 2, 1947) was a Russian philosopher, mathematician, author, teacher, and mystic. He is known as a conveyor and interpreter of the teachings of Georges Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866-1949) but was well established as an author even before he encountered Gurdjieff. Ouspensky has a lasting place in the early-twentieth-century Russian literary tradition, and as a writer of numerous books on human spiritual development. [1]

Ouspensky is chiefly remembered by his book In Search of the Miraculous, published posthumously in 1949. In this book Ouspensky recounts his meeting and subsequent association with Gurdjieff and it is generally regarded as the most comprehensive account of Gurdjieff's system of thought ever published, as it often forms the basis from which Gurdjieff and his teachings are understood. [2]

Early Years

Ouspensky was born and grew up in Moscow. His parents were part of Russia's intelligentsia, the educated elite. His mother was a painter with an interest in Russian and French literature and his father a railroad surveyor who died when Ouspensky was a child. [3][4] His father was a good amateur mathematician whose special pastime was study of the fourth dimension, which seems to be a trait he passed on to his son. For Ouspensky it became kind of a metaphysical magic bag. [5]

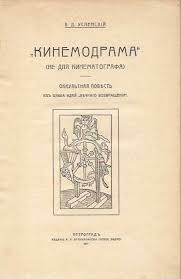

The precocious boy was dissatisfied with school and even as a youth he discriminated between “ordinary knowledge” of worldly matters and “important knowledge” concerning questions about the nature of reality, human evolution and destiny, and the acquiring of higher consciousness. Thus, he left the academic world. These particular questions preoccupied him throughout his life. In 1905 he wrote a novel titled Kinema-Drama; which was not published until 1915 and was later translated into English as The Strange Life of Ivan Osokin. The book, based on the idea of eternal recurrence popularized by Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), dramatizes the notion that eternal recurrence, or living the same life again and again, can come to an end for a person who learns its secret. To escape “the trap called life,” one must make sacrifices for many years, and even many lifetimes. [6]

Ouspensky and Theosophy

Some of Gurdjieff’s closest pupils had strong ties to Theosophy, and Ouspensky was one of them. For seven years beginning in 1907, Ouspensky researched and wrote about occult and Theosophical ideas. [7] Studying Theosophical texts, he learned that “there was a way to study religion as a body of knowledge which meant something.” [8] In 1913, two years before he met Gurdjieff, Ouspensky went on a Blavatsky-like search for esoteric knowledge in the East, staying for six years in Adyar, the headquarters of the Theosophical Society. There, Ouspensky spoke with the Society's president Annie Besant and was admitted into the inner circle. Ultimately, he returned to Russia and continued his search. [9]Upon his return he joined the St. Petersburg Theosophical Society but doubted that members were able to develop “higher faculties.” [10] Ouspensky doubted the existence of the astral world because “no proofs of the objective existence of the astral sphere are anywhere given.” [11]

However, reading Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous one can see that the book has a “strong Theosophical tone and method throughout, behind purely theoretical with no practical component. In this way it could easily be compared with [Blavatsky's work] The Secret Doctrine. It may well be worth questioning how much Gurdjieff is read through Theosophical glasses”, thanks to this book. [12] The author Petsche adds in a footnote that this idea was inspired by a meeting with the Joseph Azize in Sydney, 1/07/2010. </ref>

Later Years

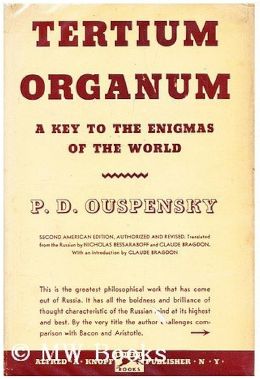

Tertium Organum, A Key to the Enigmas of the World, which he self-published in 1912 was intended to supplement Aristotle's Organon and Francis Bacon's Novum Organum. It brought Ouspensky attention and fame. It is based on the author’s personal experiments in changing consciousness; it proposes a new level of thought about the fundamental questions of human existence and a way to liberate man’s thinking from its habitual patterns. [13] Still bent on finding an esoteric school, in the winter of 1913 Ouspensky traveled to Ceylon and India. He contacted a number of schools, but they were, he said, "either of a frankly religious nature, or of a half-religious character, but definitely devotional in tone." These did not interest him. [14] Other schools promised a great deal but demanded, from the beginning, a complete surrender. "It seemed to me," he said, "there ought to be schools of a more rational kind and that a man had the right, up to a certain point, to know where he was going." [15]

Meeting G.I. Gurdijeff

Ouspensky was no stranger to the realms of higher consciousness before he met G.I. Gurdijeff. However, his introduction to Gurdijeff was a central experience in Ouspensky’s life. [16] It happened in April 1915 in Moscow and Ouspensky at once recognized the answers Gurdjieff gave to his questions, his understanding of life, were of a much different and deeper quality than anything he had ever encountered. He was particularly impressed with Gurdjieff's command of psychology, an area that he felt was his specialty, and met with Gurdjieff every day for a week before he was obligated to return to St. Petersburg. [17]

Alternatively, Ouspensky’s reputation made him attractive to Gurdjieff. “The turning point in Gurdjieff’s career came in 1915 when Ouspensky was introduced to him, a moment for which Gurdjieffg had been planning and preparing.” [18] Gurdijeff enlisted Ouspensky’s help to form a group. This time is referred to by Ouspensky as "the St. Petersburg Conditions." Formal studies under Gurdjieff began in February 1916. [19] In February 1917 Thomas and Olga de Hartmann joined the group and perhaps Sophia Grigorievna Savitsky who became known as "Mme Ouspensky," though it is not clear if they ever married. That same month civil disorder broke out in Russia and Gurdjieff left for the Caucasus. [20]

In June 1917, after four months’ service in the army, from which he was honorably discharged on account of poor eyesight, the impending revolution caused Ouspensky to consider leaving Russia to continue his work in London. But he delayed his departure to spend nearly a year in difficult political conditions with Gurdjieff and a few of his pupils at Essentuki in the northern Caucasus. [21] [22]

The first time in Essentuki lasted just six weeks. The group was led by Gurdijeff at an extremely fast pace and very little sleep and during that stay he unfolded the plan of the whole work. The members saw the beginnings of all the methods, ideas, their links, their connections and directions. [23] Suddenly, at the end of the summer, Gurdijeff announced that he was dispersing the whole group and stopping all work, which surprised and upset Ouspensky and the others. From this moment on began for Ouspensky a “separation between Gurdijeff himself and his ideas.” [24] This marked the beginning of many such reactions, identifications and separations. Though he would join Gurdjieff again in Essentuki, he would continue on to Constantinople after Essentuki was liberated in January of 1919. [25]

In the spring of 1920 Ouspensky was offered a drawing room in Constantinople in which to hold lectures. Those lectures created interest and he began forming a group of pupils. On July 7, 1920, Gurdjieff and his followers arrived in Constantinople and Ouspensky decided to work again with Gurdjieff turning over his pupils to him. At this time Ouspensky gave lectures at Gurdjieff's Institute in Constantinople. In the spring of 1921 Ouspensky noticed that Gurdjieff seemed to be going out of his way to provoke quarrels and misunderstandings. Ouspensky was alarmed by Gurdjieff's behavior and began to think of leaving and took the offer a sponsor to come to London. Mme. Ouspensky stayed with Gurdjieff. [26]

Ouspensky was well received in London and developed again his own circle of disciples. Gurdjieff joined him there in 1922 and acquired some of his students. Gurdjieff was refused permanent entry in London and eventually moved to Paris founding his own institute at Fontainebleau-Avon in France. In 1924 Ouspensky refused to stay at Gurdjieff’s Institute at Prieuré des Basses Loges, and he announced the independent nature of his future work. The final break came in 1931 when Ouspensky was denied all access to Prieuré. [27] Later, after Gurdjieff closed that Institute, he sent Mme Ouspensky to her husband in England. Though the Ouspenskys personal relationship remained platonic, they did share the responsibility of teaching in both England and America. [28]

Historico-Psychologicl Society

Ouspensky continued to teach and to write in London and founded the Historico-Psychological Society. He was the official lecturer and began drafting rules to be adhered to by the Society members. He thought that these prohibitive rules would promote consciousness: pupils were never to mention Gurdjieff, never address each other by their Christian names, never speak together around strangers, never speak to anyone who had left the groups. [29]. However, World War II made life in London difficult. He also taught for a time in Lynn in Surrey, but decided to go to the United States, where he held large meetings in New York and New Jersey from 1941 to 1946. He left instructions on how to continue with the Work. Although in failing health, he returned to England in 1947. Before his death in October of that year, he told his disciples that the work as they had known it could not continue without him. However, they were free to pursue the truth in their own way. [30]

Writings

Ouspensky is best known for Searching for the Miraculous, which was not published till after his death. But he wrote several other books.

The Fourth Dimension was published in St. Petersburg in 1910. It is a philosophical and mathematical exploration of the concept of higher dimensions by P.D. Ouspensky. The book begins with an overview of the three dimensions of space and one dimension of time that we experience in our daily lives, and then delves into the possibility of a fourth dimension. Ouspensky uses analogies and thought experiments to help readers understand the concept of higher dimensions and how they might be experienced. He also explores the implications of higher dimensions for our understanding of reality and consciousness. Tertium Organum, which he self-published in Russia in 1912, was published in New York in 1922, became within a few years a best-seller in America and made him a world-wide reputation. A New Model of the Universe, a collection of essays published earlier in Russia, was published in London in 1930. [31]

The Fourth Way (1957), consisting of records of Ouspensky’s meetings from 1921 to 1947, was published under the supervision of Ouspensky’s wife. The term “Fourth Way” means bringing the life of the fakir, the monk, and the yogi into ordinary life, to experience eternity doing simple tasks. This fourth form of consciousness is the beginning of the transition to cosmic consciousness—the state of the spirit beyond time and the cycles of life and death. [32]

Ouspensky’s “Psychological Lectures,” given from 1934 to 1940, were published posthumously as The Psychology of Man’s Possible Evolution (1981). Here Ouspensky contends that living beings are progressing through levels of being from the one-dimensional (plants and lower animals), to the two-dimensional (higher animals), to the three-dimensional (ordinary humans). However, some humans who strive to do so can pass beyond the mere sensory consciousness of three dimensions in understanding time as the fourth dimension of space. There is a fifth dimension perpendicular to the line of time, which is the line of eternity, or an infinite number of finite points in time. [33]

Last Years

When Ouspensky’s health declined, he decided to leave America and sailed for England on January 18, 1947. Five weeks later, on February 24, he held the first of six meetings at Colet Gardens. Ouspensky baffled many of his students by denying that he had ever taught a System, saying he had never given a teaching and that he had no teaching to give. Those in attendance tried to understand; some believed this was a teaching device. No one considered that what he said was what he believed. In his last days, Ouspensky was driven by his student Rodney Collin-Smith for exhausting car rides to impress familiar locations on his memory. Ouspensky would also push his body, making himself stay up long hours. On October 2, 1947, Ouspensky died at Lyne Place in the arms of Rodney Collin-Smith. He is buried in the courtyard of Lyne Church.[34][35]

MMe Ouspensky

Mme Ouspensky was very clear as to who was the teacher and who the pupil. "I do not pretend to understand Georgy Ivanovitch. For me he is X. All that I know is that he is my teacher and it is not right for me to judge him, nor is it necessary for me to understand him. No one knows who is the real Georgy Ivanovitch, for he hides himself from all of us. It is useless for us to try to know him, and I refuse to enter into any discussions about him. Thus, when Ouspensky and Gurdjieff separated, she stayed with Gurdjieff until 1924 when Gurdjieff sent her to her husband. After that she went back and forth. [36] [37]

Gurdjieff owed much to Mme. Ouspensky. “When P. D. Ouspensky died in 1947, Mme Ouspensky advised not only his students (there were about 1,000 in London alone) but also her own to go to Gurdjieff in Paris. Many, because of the war and the ban Ouspensky had placed on speaking of Gurdjieff, were not even aware he was alive or feared he had become mad or senile.” [38] Even more important was her decision to show Gurdjieff her husband’s drafted book, then called "Fragments of An Unknown Teaching," which Ouspensky had left unpublished for eighteen years. [39] Upon reading it, Gurdjieff said, "Very exact is. Good Memory. Truth was so. [40] Moore adds this quote from Gurdjieff: “Before I hate Ouspensky; now I love him.” [41] He instructed Mme. Ouspensky to publish the book, but to wait until after his own book Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson came out. She published in America under the title In Search of the Miraculous in 1949. Beelzebub’s Tales were published in 1950.

The Fourth Way

Ouspensky was fascinated by the idea of higher dimensions. He explored the fourth dimension as a concept that could explain phenomena that are beyond the ordinary understanding of space and time. [42] For Ouspensky, the fourth dimension was a way to delve into higher states of reality and consciousness – in simple terms, being aware of being aware.

Another major impetus for widening interest in higher dimensions of space was Theosophy. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky refers in The Secret Doctrine to the Fourth Dimension, but just in passing. It was Charles Webster Leadbeater who compared the Theosophical ides of “astral vision” to four-dimensional sight. [43] In fact, many Theosophists became actively interested in the fourth dimension and Kandinsky, Frantisek Kupka and Piet Mondrian were naturally sympathetic toward the fourth dimension because of their Theosophical beliefs. [44]

The Fourth Way, as articulated by Ouspensky and his teacher, G.I. Gurdjieff, is a spiritual path that integrates the methods of the three traditional ways: the way of the fakir (physical discipline), the way of the monk (faith and devotion), and the way of the yogi (knowledge and mind control). The Fourth Way is about achieving higher states of consciousness and self-awareness while living an ordinary life. [45]

Both the concept of the fourth dimension and the Fourth Way involve the idea of reaching higher levels of understanding and perception. The fourth dimension, in a metaphorical sense, can represent a higher state of consciousness, similar to what the Fourth Way aims to achieve through spiritual development.

Additional resources

- Ouspensky, Peter Demianovich in Theosophy World

Notes

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ Pentland, John. P. D. Ouspensky, Gurdjieff International Review, Winter 1998/1999, http://www.gurdjieff.org/pentland2.htm Pent Accessed on 8/1/24

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. In Search of P.D. Ouspensky: The Genius in the Shadow of Gurdjieff. Quest Books, Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill., 2004, pg. 10

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel, Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1) June 2011, page 113. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Webb, James. The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1980, pg.111

- ↑ Webb, James. The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1980, pp 126- 134

- ↑ Butkovsky-Hewitt, Anna; Cosh, Mary.With Gurdjieff in St. Petersburg and Paris, Routledge & K. Paul; First Edition, 1978, pp 16-18, 29

- ↑ Ouspensky, P.D. A New Model of the Universe. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Ltd., London, 1931, p. 111

- ↑ Petsche, Johanna. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky: Western Esoteric Teachers in Parallel, Literature & Aesthetics 21 (1) June 2011, page 114. PDF-File available online. Accessed on 8/2/2024.

- ↑ Pentland, John P. D. Ouspensky, Gurdjieff International Review, Winter 1998/1999, http://www.gurdjieff.org/pentland2.htm Pent Accessed on 8/1/24

- ↑ Patterson, William Patrick. Struggle of the Magicians. Fairfax, CA: Arete Communications, 1996, pg. 10

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. In Search of P.D. Ouspensky: The Genius in the Shadow of Gurdjieff. Quest Books, Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill., 2004, pg. 3

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Webb, James. The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1980, pg 133-134

- ↑ Patterson, William Patrick. Struggle of the Magicians. Fairfax, CA: Arete Communications, 1996, pp 24-25

- ↑ Patterson, William Patrick. Struggle of the Magicians. Fairfax, CA: Arete Communications, 1996, pg. 43

- ↑ Pentland, John. P. D. Ouspensky, Gurdjieff International Review, Winter 1998/1999, http://www.gurdjieff.org/pentland2.htm Accessed on 8/1/24

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Ouspensky, P.D. In Search of the Miraculous. A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., New York, 1949; pg. 346

- ↑ Ouspensky, P.D. In Search of the Miraculous. A Harvest Book, Harcourt, Brace & World Inc., New York, 1949; pg. 367-368

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947) https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ Pentland, John P. D. Ouspensky, Gurdjieff International Review, Winter 1998/1999, http://www.gurdjieff.org/pentland2.htm Pent Accessed on 8/1/24

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ Saltzman, Judy. Ouspensky, P.D. Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 10, 2nd ed., Gate, 2005

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947). https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/2/2024

- ↑ Lachmann, Gary. In Search of P.D. Ouspensky: The Genius in the Shadow of Gurdjieff. Quest Books, Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill., 2004, pp.268-270

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. MMe Ouspensky 1878 – 1961. https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/mmeouspensky.htm. Accessed on 8/6/2024

- ↑ Bennet, John. Witness Charlestown, WV. Claymont Communications, 1983, p. 128

- ↑ The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives. P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947) https://gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/pdouspensky.htm; Accessed on 8/6/2024

- ↑ Patterson, William Patrick. Struggle of the Magicians. Fairfax, CA: Arete Communications, 1996, pg. 220

- ↑ Patterson, William Patrick. Struggle of the Magicians. Fairfax, CA: Arete Communications, 1996, pg. 220

- ↑ Moore, James. Gurdjieff, The Anatomy Of A Myth. Element Books Ltd. Great Britain, 1991; pg. 205

- ↑ Henderson, Linda Dalrymple. The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1983. Pg. 25

- ↑ Leadbeater, C.W. The Astral Plane: Its Scenery, Inhabitants and Phenomena. London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1910, p. 19

- ↑ Henderson, Linda Dalrymple. The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1983. pp. 31-32

- ↑ Ouspensky, P.D. The Fourth Way.https://selfdefinition.org/gurdjieff/Ouspensky-The-Fourth-Way.pdf Accessed on 8/6/24. Chapter 4