Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570 BC – c. 495 BC) was an Ionian Greek pre-Socratic philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the spiritual movement called Pythagoreanism. As a mystic he made influential contributions to philosophy and religion, while he is also regarded as a great mathematician and scientist. He was an original thinker whose concepts strongly influenced the course of all Western learning. [1]

Pythagoras left his homeland in search of knowledge and after many years of travel he returned to the Greek world and was initiated into mystery cults in Greece and Crete before finally settling in Crotona where he set up an order, the Pythagorean Brotherhood.

Survivors of the brotherhood scattered throughout the Greek world, carrying Pythagoras’s teachings with them. From them and their students, the traditions of Western occultism ultimately descend.

[2]

Birth, Parentage, and Name

As Pythagoras he was born about 582 B.C. at Sidon, in Phoenicia, and died about 500 B.C. His parents, Mnesarchus and Pythias, descendants of Ancæus, who colonized the island of Samos by order of the Pythian oracle, were promised “a son who would be useful to all men through all time.” They were a family of prominence in Samos, very religious and devoted to the worship of Apollo. The father was a cutter of precious stones and a wealthy jeweler.

The birth of Pythagoras was a consecrated ordeal. His parents were sent from their home in Samos to Sidon, in Phoenicia, where the promised son was conceived, formed, and born, away from the disturbing influence of his own land. At the age of one he was taken to the Temple of Adonai in the valley of Liban, to be blessed by the High Priest and consecrated to Apollo.

[3]

At eighteen he became the pupil of the Orphist Pherecydes and learnt from him the secrets of the Orphic doctrine. He also studied under Anaxinander, the Natural Philosopher, and Thales the Astronomer. Having learnt all these sages could teach him, he travelled to Phoenicia, Egypt, Babylon, Persia, and India for the purpose of studying the Wisdom of these countries and was also in touch with the Jews and Druids. In Egypt he spent twenty-two years and was initiated into the most sacred of the Mysteries.

At the age of fifty-six he returned to Samos, where he introduced a symbolical teaching. But the Samians, being too much attached to worldly things, did not respond to his teaching, and Pythagoras therefore left them and settled in Magna Graecia in Italy. There in 530 B.C. he founded the first community at Crotona.

Pythagoras has been celebrated as a Trainer of Souls. The great brotherhood which he founded remains as an example of the ideal community and has left an enduring influence in the world. The Pythagorean System contains the quintessence of all the elements necessary for living the truly religious, philosophical and mystical life which leads straight to the Divine.

The Golden Verses are a most valuable epitome of the Pythagorean ethical teachings. Although they are sometimes known as “The Golden Verses of Pythagoras”, it is improbable that they were composed by Pythagoras himself. According to tradition, the Verses were put into their present form by Lysis, one of the most eminent of the Pythagoreans, and it is possible that he embodied in their metrical form many of the actual sayings of his master. The Golden Verses do indeed give all the essential principles required for the right ordering of physical, affectional, intellectual, and devotional life. [4]

Death

Accounts differ concerning the origin of the hostilities which arose against the Pythagoreans and also to where Pythagoras was at the time of his death. [5][6]

One account says that he was banished from Crotona and fled to Metapontum where he died [7][8]after a self-imposed fast of forty days.

Many accounts point out that the sovereign influence of Pythagoras’ great spirit and character stirred up jealousies and hatred. [9]His power lasted for a quarter of a century but eventually it caused alarm to the authorities. [10]He was ninety when reaction came. The spark came from Sybaris, the rival of Croton. After an uprising five hundred exiles asked Crotons for asylum, but the Sybarites asked their extradition and the magistrates agreed at first until Pythagoras intervened. Thus, Sybaris declared war on Croton but were defeated and destroyed. The reprisals were not approved by Pythagoras. Political negotiation afterwards increased the hatred for the Pythagoreans. Cylon, who had been rejected by Pythagoras as a disciple due to his violent nature organized a large body of people when public opinion turned against the Order. When forty members met at a private house, Cylon attacked them, set the house on fire and thirty-eight of them including Pythagoras were killed. Only his disciples Archippus and Lysis escaped. The Order was dispersed but its remnants spread into Sicily and Greece, everywhere sowing the word of the master. [11]

The Academy

After having passed years of wandering and apprenticeship Pythagoras arrived in Crotona with certain definite views on the structure of the universe, on the nature of man and his place in it, and views on his own calling. He felt called upon to form and lead a human community to teach people to take their appropriate place in the cosmos. [12]

Thus, Pythagoras established around the year 529 B.C. his Academy at Crotona and it was a secret scientific-religious brotherhood. The number of disciples and auditors numbered several hundred. The more serious students were divided into the classes of Probationers or Exoterics, and Mathematicians or Esoterics. To advance in this academy, it was required that science, especially mathematics and astronomy, be mastered as subjects best fitted for the enlightenment of man. The disciples needed to deepen their religious insights, master their feelings, and purify their souls.

Admission to Pythagoras’ Academy was by choice, which was selective and by trial, which was difficult. Pythagoras lectures were delivered from behind a screen and were veiled in language to be fully understood only by the most advanced disciples.

Before admission to the Academy, Pythagoras would know the petitioner: his relations with parents, friends, and associates, the appropriateness of his laughter, silence, and manner of discourse, his handling of anger, passion, and ambition, his capacity for joy and grief, and what caused these sentiments. All elements of the personality were seriously appraised.

Included in the pre-requisition was five years of silence. Pythagoras also advised his disciples that it is best to commence one’s day in silent meditation, and thus compose one’s own soul. He felt that meditation placed one in the presence of powerful constructive and directive forces. There were also disciplines regarding food and sleep, temperance, and not being attached to honors. Important too, was their strict rule of secrecy concerning speaking of their more profound doctrines with outsiders. [13]

A general classification of the Pythagorean teaching is according to degrees:

1) First Degree: Preparation was the keynote. The accepted disciples were distributed into different classes according to their respective merits.

2) Second Degree: Purification was the keynote and was taught and cultivated. Music was used as a powerful means. The disciples came into direct contact with the master, which meant a real initiation.

3) Perfection was the keynote, in which stage the student was taught esoteric cosmogony and psychology, or the evolution of the soul. The disciple was led from darkness into light.

4) Epiphany was the keynote, the vision above through the extended consciousness, which set forth an ensemble of a profound regenerating view of things on earth.

True friendship was inculcated, had to be free from contest and contention, and should not be abandoned on account of misfortune.

Disciples were taught that the soul is immortal, that they are preexistent to bodies, that there is an innumerable company of Souls and that there is transmigration or reincarnation of the soul. [14]

The senators and rulers of Crotona, realizing the great benefit they had derived from the discourses of Pythagoras, asked him to speak to the boys in the Temple of Apollo and to the women in the Temple of Juno. Pythagoras’ conservative ethics for women revolved around cult practices and their relationships with their husbands. The women were urged to be honest, good, faithful and obedient to their husbands, without contention and strife, and to dress simply and modestly. He exhorted them never to speak ill of others and always to strive to deserve the good report of all. He said they should present handmade things at the altar as a sacrifice to the gods. [15][16]

The boys were commanded to be honest and industrious, as habits formed in youth would bear fruit in age. They were urged to diligently pursue knowledge and said that boys were especially beloved by the gods.[17]

The Family of Pythagoras

Among the women who followed the teaching of Pythagoras was a young, beautiful girl with the name Theano. At that time Pythagoras was nearly sixty but very healthy. When Theano confessed her love to him, he married her. She entered so completely into the thought of her husband, that after his death she served at the center of the Pythagorean Order. They had two sons and a daughter together. His younger son Telaugus became the tutor of Empedocles and transmitted to him the secrets of the teachings.

Pythagoras was a model family. His house was called the temple of Ceres, and his court the temple of the Muses.[18]

Sacred Geometry, Music, and Orpheus

To understand Pythagoras one cannot minimize his preoccupation with numbers and their application to specific concepts and objects. His theory applies specific numbers to everything, both animate and inanimate – for example, to man, plant, and earth. He also applied numbers to concepts: two is equated with opinion, four with justice, five with marriage, seven with timeliness.

The decad was regarded as the inclusive, culminating, sacred number. The Pythagoreans, therefore, divided the universe into ten spheres: first was the circle of the Divine Fire, then the seven spheres of the planets, the earth, and Antechthon, which they proposed as a counter earth. This we never see, since its motion always keeps it at 1800 from the earth, kept from view by the sun. They conceived of the heavenly bodies, not so much as physical bodies, but as energy centers, serving as agencies through which Divine intelligence expresses.

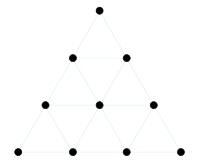

The Tetractys, representing universal forces and processes, forms a pyramid by the use of 10 dots. It was the most revered symbol of the Pythagoreans. To contrast the figure, four dots are used to form the base, three are placed above these, and then two upon them, and finally one. The one is unity, the two diversity, the three equilibrium, while the four is the smallest number of lines that can enclose a square.[19]

The Pythagorean theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry among the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares on the other two sides.

[20]

According to Mme. Blavatsky, what Orpheus delivered in hidden allegories, Pythagoras learned when he was initiated into the Orphic mysteries (and Plato received a perfect knowledge of them from Orphic and Pythagorean writings). [21]

This was also the opinion of other scholars, who wrote that Pythagoras derived most of what we associate with the idea of Pythagoreanism, including the numbers, from Orpheus. In fact, from quite early on a number of Orphic texts were even attributed to him, both confirming his Orphism and suggesting the nature of Orpheus to be an angelic, initiatic state perhaps similar to that of Hermes Trismegistus. The Pythagoreans received from the theology of Orpheus the principles of intelligible and intellectual numbers; and not only numbers, but the entire religious framework of their study was Orphic from the Greek point of view. That is, we can find the whole of Pythagorean number theory in Orpheus, but embodied in mythological, symbolic, religious language. [22]

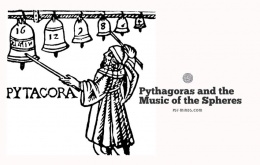

Music in the Pythagorean philosophy occupied a very important place and was used as a powerful means by Pythagoras. Pythagoras was of the opinion that music contributed greatly to health if it was used in an appropriate manner. He called the medicine which is obtained through music by the name of purification; it was that which cured moral ills and produced purification. During the period labeled Second Degree, the occult doctrine was expounded by the use of music and the mysterious science of number. [23] It is said that he was the first to teach the Greeks the tonic relations of the musical scale, and invented for them the monochord, a one-stringed instrument, used in measuring the musical intervals. Upon these relations he built his celebrated doctrine of the Harmony or Music of the Spheres. [24][25]

Mme. Blavatsky wrote in the Secret Doctrine:

“It is on number seven that Pythagoras composed his doctrine on the Harmony and Music of the Spheres, calling “a tone” the distance of the Moon from the Earth; from the Moon to Mercury half a tone, from thence to Venus the same; from Venus to the Sun l 1/2 tones; from the Sun to Mars a tone; from thence to Jupiter 1/2 a tone; from Jupiter to Saturn 1/2 a tone; and thence to the Zodiac a tone; thus making seven tones — the diapason harmony. All the melody of nature is in those seven tones, and therefore is called “the Voice of Nature.”” [26]

Orpheus and Pythagoras embody two fundamentally different perspectives on music that together circumscribe the foundation of Western attitudes toward the art. As a musician, Orpheus demonstrated music’s effect; as a philosopher, Pythagoras explained its essence. Until at least the sixteenth century, and in many cases beyond, Pythagoras was credited with having discovered music’s essence—what it is—while Orpheus was hailed as the paradigmatic musician who demonstrated music’s effect—what it does. These contrasting figures were never perceived in opposition to each other, however, nor even as two sides of the same coin. Their relationship was understood as one of mutual reinforcement: Pythagoras’s explanation of music’s essence was at the same time an explanation of its effect, as realized through the hands of Orpheus.[27]

Legacy an Theosophical Vies

Some of the authorities hold that Pythagoras himself left no writings; others affirm that this is not true. The teachings of Pythagoras were later found among the Essenes, a Jewish sect in Palestine in the time of Christ. Diogenes said that in his time there were in existence three volumes written by Pythagoras; one on education, one on politics, and one on natural philosophy but that several other books had disappeared.

The efficacy of Pythagoras’ teachings has lasted through the centuries; its flame has never been extinguished but religiously preserved and transmitted from generation to generation by the elect, to whom has been confided by degrees the sacred deposit. He stands an exponent of those immutable Laws that rule man’s pilgrimage through the vicissitudes of life; of that power which transmutes sorrow into blessing, darkness into light, death into immortality, of that Love which makes man a Master of the Wisdom of the World. The Pythagoric life is a specimen of the greatest perfection in virtue and wisdom which can be obtained by man in the present state. [28]

Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

The most famous of mystic philosophers, born at Samos, about 586 B.C. He seems to have travelled all over the world, and to have culled his philosophy from the various systems to which he had access. Thus, he studied the esoteric sciences with the Brachmanes of India, and astronomy and astrology in Chaldea and Egypt. He is known to this day in the former country under the name of Yavanâchârya (“Ionian teacher”). After returning he settled in Crotona, in Magna Grecia, where he established a college to which very soon resorted all the best intellects of the civilised centres. His father was one Mnesarchus of Samos, and was a man of noble birth and learning. It was Pythagoras. who was the first to teach the heliocentric system, and who was the greatest proficient in geometry of his century. It was he also who created the word “philosopher”, composed of two words meaning a “lover of wisdom”—philo-sophos. As the greatest mathematician, geometer and astronomer of historical antiquity, and also the highest of the metaphysicians and scholars, Pythagoras has won imperishable fame. He taught reincarnation as it is professed in India and much else of the Secret Wisdom.[29]

H.P.B. mentions Pythagoras numerous times in her works. She wrote that he was an initiate, praised him for his severe morality, and considered him a pure philosopher deeply versed in the profounder phenomena of nature whose great aim it was to free the soul from the fetters of sense and force to realize its powers.[30][31]She wrote, that Pythagoras established the whole Copernicus system by the Books of Hermes 2000 years before Galileo’s predecessor was born and that he found and studied in them the whole Science of divine Theogony, of the communication with, and the evocation of the world’s Rectors, the nativity of each planet and of the universe itself, the formulae of incantations and the consecration of each portion of the human body to the respective Zodiacal sign corresponding to it. [32]

Master K.H., in one of his letters stated that some of Galileo's discoveries had been prompted by a Pythagorean MSS. in his possession.[33]

Like many other Eastern teachers of wisdom, Pythagoras was able to diagnose earlier existences. He said he had various incarnations in India; was the Phrygian king Midas; Euphorbus, the son of Panthos. Aethalides, the son of Hermes was also included in the list. [34]

Master K.H. was according to C.W. Leadbeater the reincarnation of Pythagoras. Before being reincarnated as K.H. he reincarnated as Ngarjuna, a great teacher of Buddhist philosophy.[35]

Online Resources

Articles

- Pythagoras and his School by Raghavan Iyer

- Pythagoras at WisdomWorld.org

- The Pythagorean Science of Numbers at WisdomWorld.org

- Pythagoras in Theosophy World

Pamphlets

- The Pythagorean Way of Life byHallie Watters. Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1926. Second edition; preface by C. W. Leadbeater.

Video

- Turning-Points for the West: From Pythagoras and Plato through Gnosticism and Neoplatonism by Stephan Hoeller and Tony Lysy

Notes

- ↑ Hall, Manly. Foreword: Pythagoras by Thomas Stanley. The Philosophical Research Society, Inc. 1970. Los Angeles, Ca. Page IV

- ↑ Greer, John Michael. The Occult Book. Sterling, N.Y. 2017, page 1

- ↑ <i<Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Page 3 ff.

- ↑ Editors of the Shrine of Wisdom. The Golden Verses of the Pythagoreans. The Shrine of Wisdom, London, page 7

- ↑ <i<Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Page 50

- ↑ Riedweg, Christop. PythagorasChapter 1: Fiction and Truth. https://www.hoopladigital.com/play/12426271. Accessed on 2/25/20

- ↑ C.W. Leadbeater. In the World’s Service.Pythagoras. A Future World Teacher. In: The Young Citizen, February 1913.

- ↑ F.S. Darrow. Life and Teachings of Pythagoras. https://universaltheosophy.com/articles/life-and-teachings-of-pythagoras/. Accessed on 2/21/20

- ↑ Shuré, Eduard. The Great Initiates. A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Harper & Row, San Francisco. Page 365 ff.

- ↑ C.W. Leadbeater. In the World’s Service.Pythagoras. A Future World Teacher. In: The Young Citizen, February 1913.

- ↑ Shuré, Eduard. The Great Initiates. A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Harper & Row, San Francisco. Page 365 ff.

- ↑ Bamford, Christopher. Introduction: Homage to Pythagoras. In: Homage to Pythagoras. Rediscovering Sacred Science.Lindisfarnee Press, Hudson, N.Y. 1980-1982. Page 27

- ↑ Stanley, Thomas. Pythagoras. The Philosophical Research Society, Inc. 1970. Los Angeles, Ca. Page VII

- ↑ Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Pages 29 - 33

- ↑ Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Page 19

- ↑ Riedweg, Christop. PythagorasChapter 1: Fiction and Truth. https://www.hoopladigital.com/play/12426271. Accessed on 2/25/20

- ↑ Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Page 19

- ↑ Shuré, Eduard. The Great Initiates. A Study of the Secret History of Religions. Harper & Row, San Francisco. Page 359 ff.

- ↑ Stanley, Thomas. Pythagoras. The Philosophical Research Society, Inc. 1970. Los Angeles, Ca. Page IX

- ↑ Pythagora’s theorem. https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=pythagoras+theorem&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8. Accessed on 2/13/20

- ↑ H.P. Blavatsky. Collected Writings, Volume XIV, page 309. http://www.katinkahesselink.net/blavatsky/articles/v14/ph_066.htm. Accessed on 2/19/20

- ↑ Bamford, Christopher. Introduction: Homage to Pythagoras. In: Homage to Pythagoras. Rediscovering Sacred Science.Lindisfarnee Press, Hudson, N.Y. 1980-1982. Page 14

- ↑ <i<Pythagoras, By a Group of Students. The American Theosophist, Krotona, Hollywood; Los Angeles, Ca. Pages 30 and 45.

- ↑ F.S. Darrow. Life and Teachings of Pythagoras. https://universaltheosophy.com/articles/life-and-teachings-of-pythagoras/. Accessed on 2/21/20

- ↑ Riedweg, Christop. PythagorasChapter 1: Fiction and Truth. https://www.hoopladigital.com/play/12426271. Accessed on 2/25/20

- ↑ Blavatksy, H.P. Secret Doctrine.Volume 2, page 601. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sd/sd2-2-12.htm. Accessed on 2/25/20

- ↑ Bonds, Mark Evan. Orpheus and PythagorasOsford Scholarship Online. https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199343638.001.0001/acprof-9780199343638-chapter-2. Accessed on 2/20/20

- ↑ By a Group of Students. Pythagoras The American Theosophist. Los Angeles, Ca. 1914. Page 52 ff

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Theosophical Glossary (Krotona, CA: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973), 266.

- ↑ F.S. Darrow. Life and Teachings of Pythagoras. https://universaltheosophy.com/articles/life-and-teachings-of-pythagoras/. Accessed on 2/21/20

- ↑ Index. Pythagoras. http://www.katinkahesselink.net/blavatsky/articles/v15/cum_index_p.htm Accessed on 2/21/20

- ↑ Blavatsky, Collected Writings, mainly in volume XIV, page 347.

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 93b (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 311.

- ↑ Riedweg, Christop. PythagorasChapter 1: Fiction and Truth. https://www.hoopladigital.com/play/12426271. Accessed on 2/25/20

- ↑ Leadbeater, C.W. Pythagoras. A Future World Teacher. In: “The Young Citizen”, February 1913. Page 58