Herbert Spencer: Difference between revisions

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

He contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, literature, biology, sociology, and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English-speaking academia. | He contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, literature, biology, sociology, and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English-speaking academia. | ||

== | == Agnosticism == | ||

Spencer's reputation among the Victorians owed a great deal to his agnosticism, and was to gain much notoriety from his repudiation of traditional religion | Spencer's reputation among the Victorians owed a great deal to his agnosticism, and was to gain much notoriety from his repudiation of traditional religion. However, Spencer insisted that he was not concerned to undermine religion in the name of science, but to bring about a reconciliation of the two. | ||

Spencer argued that either from the point of view of religion or science, whether we are concerned with a Creator or the substratum which underlies our experience of phenomena, we can frame no conception of it. Therefore, Spencer concluded, religion and science agree in the supreme truth that the human understanding is only capable of "relative" knowledge. This is the case since, owing to the inherent limitations of the human mind, it is only possible to obtain knowledge of phenomena, not of the reality ('the absolute') underlying phenomena. For this reason [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky|H. P. Blavatsky]] wrote that Spencer "like Schopenhauer and von Hartmann, only reflects an aspect of the old [[esotericism|esoteric]] philosophers, and hence lands his readers on the bleak shore of Agnostic despair..."<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''The Secret Doctrine'' vol. I, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 19, fn.</ref> | |||

He called this principle "the Unknowable", and thought that the Unknowable represented the ultimate stage in the evolution of religion, the final elimination of its last anthropomorphic vestiges. In reference to this position, Mme. Blavatsky wrote: | |||

<blockquote>Herbert Spencer has of late so far modified his Agnosticism, as to assert that the nature of the “First Cause,” which the [[Occultism|Occultist]] more logically derives from the “Causeless Cause,” the “Eternal,” and the “Unknowable,” may be essentially the same as that of the [[Consciousness]] which wells up within us: in short, that the impersonal reality pervading the Kosmos is the pure [[noumenon]] of thought. This advance on his part brings him very near to the [[Esotericism|esoteric]] and [[Vedanta|Vedantin]] tenet.<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''The Secret Doctrine'' vol. I, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 14.</ref></blockquote> | |||

== Notes == | |||

<references/> | |||

Revision as of 16:20, 7 July 2014

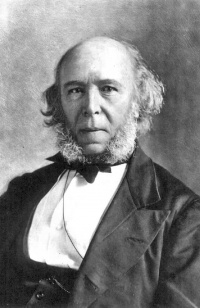

Herbert Spencer (April 27, 1820 – December 8, 1903) was an English philosopher, biologist, anthropologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era. He developed an all-embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies. Spencer is best known for coining the expression "survival of the fittest", which he did in Principles of Biology (1864), after reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Yet as Spencer extended evolution into realms of sociology and ethics, he also made use of Lamarckism.

He contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, literature, biology, sociology, and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English-speaking academia.

Agnosticism

Spencer's reputation among the Victorians owed a great deal to his agnosticism, and was to gain much notoriety from his repudiation of traditional religion. However, Spencer insisted that he was not concerned to undermine religion in the name of science, but to bring about a reconciliation of the two.

Spencer argued that either from the point of view of religion or science, whether we are concerned with a Creator or the substratum which underlies our experience of phenomena, we can frame no conception of it. Therefore, Spencer concluded, religion and science agree in the supreme truth that the human understanding is only capable of "relative" knowledge. This is the case since, owing to the inherent limitations of the human mind, it is only possible to obtain knowledge of phenomena, not of the reality ('the absolute') underlying phenomena. For this reason H. P. Blavatsky wrote that Spencer "like Schopenhauer and von Hartmann, only reflects an aspect of the old esoteric philosophers, and hence lands his readers on the bleak shore of Agnostic despair..."[1]

He called this principle "the Unknowable", and thought that the Unknowable represented the ultimate stage in the evolution of religion, the final elimination of its last anthropomorphic vestiges. In reference to this position, Mme. Blavatsky wrote:

Herbert Spencer has of late so far modified his Agnosticism, as to assert that the nature of the “First Cause,” which the Occultist more logically derives from the “Causeless Cause,” the “Eternal,” and the “Unknowable,” may be essentially the same as that of the Consciousness which wells up within us: in short, that the impersonal reality pervading the Kosmos is the pure noumenon of thought. This advance on his part brings him very near to the esoteric and Vedantin tenet.[2]