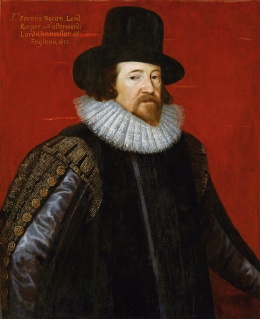

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St. Alban, (January 22, 1561 – April 9, 1626), was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, jurist, orator, essayist, and author. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon has been called the creator of empiricism. His works established and popularized inductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the Baconian method, or simply the scientific method. After his death, his works remained extremely influential, especially during the scientific revolution.

Early Years

Francis Bacon was born on January 22, 1561, in London, England. According to most historians, he was the youngest of eight children born to Sir Nicholas Bacon, who held the important position of Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Queen Elizabeth I. Francis' mother, Lady Ann Cooke, was an accomplished scholar who came from a politically influential family. [1][2]

However, there are researchers stating that there is evidence pointing to Francis Bacon being the eldest living son of Queen Elizabeth I who was adopted by Sir Nicholas and Lady Anne Bacon. The historian William Camden named Earl of Leicester as the father of the Queen’s offspring in his Annals of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, published in 1615. Queen Elisabeth I also has given birth to a second son, Robert Deveraux, later known as Earl of Essex (Nov. 10, 1565-Feb. 25, 1601).

[3]

Together with Anthony, an older son of Sir Nicolas Bacon, Francis grew up in a context determined by political power, humanist learning, and Calvinist zeal. Sir Nicolas Bacon had built a new house in Gorhambury in the 1560s, and Francis was educated there for some seven years; later, along with Anthony, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge (1573–5), where he sharply criticized the scholastic methods of academic training. [4]

[[File: StatueOfFrancisBacon.jpg|right|260px|thumb|Memorial to Bacon in the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge]

He remained at Trinity for two years and was admitted to the Gray's Inn legal society in 1576. Bacon soon grew weary of his study of law, however, and traveled to France, where he lived with the English ambassador in Paris. He was forced to return home in 1579 when Sir Nicolas Bacon died, and afterwards remained in England, eventually becoming a lawyer in 1582. [5]

Political Career

Bacon's public life began in 1584, when he was elected to Parliament's House of Commons. He quickly distinguished himself as a skilled orator and a clever politician. Thanks to the influence of his political allies, he was named to Queen Elizabeth's Learned Council of advisors in 1591 but fell out of royal favor when he criticized the queen's proposed tax plan for the war with Spain. [6]

His political advancement was stalled until 1603, with the succession of King James I during whose reign Bacon rose to power. He was knighted in 1603 and was created a learned counsel a year later. He commenced the political issues of the union of England and Scotland, and worked towards religious toleration, endorsing a middle course in dealing with Catholics and nonconformists. Bacon married Alice Barnhem, the young daughter of a rich London alderman in 1606. One year later he was appointed Solicitor General. He was also dealing with theories of the state and developed the idea, in accordance with Machiavelli, of a politically active and armed citizenry. In 1608 Bacon became clerk of the Star Chamber; and at this time, he made a review of his life, jotting down his achievements and failures. [7]

[[File: Bacon_vs_Parliament.jpg|right|260px|thumb|Bacon and members of Parliament on the day of his 1621 political fall]

He assumed his father's former position as Lord Keeper in 1617, and by the following year, he had ascended to the office of Lord Chancellor, the country's highest political and judicial post, and was given the noble title Viscount of St. Albans. But in 1621, Bacon's political life was upended by scandal. His enemies accused him of obstructing justice and accepting bribes. However, it was common practice for officials to accept gifts from parties involved in legal disputes at the time. As more accusations surfaced, Bacon pleaded guilty and submitted a full confession to the House of Lords, [8] possibly because the King asked him to do so fearing a revolution. [9] He lost all his offices and his seat in Parliament but retained his titles and his personal property. [10]

The Philosophy of Science

After being banished from the world of politics, Bacon retired to Gorhambury Manor and turned to his literary work. During his time as a politician, he had already published several scholarly works and had planned a large, multi-volume work entitled "Instauratio Magna" ("Great Restoration"), in which he intended to set forth his philosophy on the nature of science and knowledge. [11] At his manor he started to turn out work after work of prose, philosophy, and several secret volumes within five years. [12] [[File: Old-Gorhambury-House.jpg|left|260px|thumb|Remains of the family estate in Gorhambury] In England three systems of thought prevailed in the late 16th century: Aristotelian Scholasticism, scholarly and aesthetic humanism, and occultism or esotericism, the pursuit of mystical analogies between man and the cosmos, or the search for magical powers over natural processes, as in alchemy. Although its most famous exponent, Paracelsus was German, occultism was well rooted in England, appealing to the individualistic style of English credulity. Bacon had also some affinity to ideas from Plato’s thought of cosmology.[13] Bacon argued that traditional learning since the Middle Ages was deficient because it was not based on sound logic. He believed that the human mind was capable of solving the problems of disease, war, and poverty, but was too often distracted by generalizations and poor judgement. In his writings, Bacon stressed the importance of separating religion and "magical sciences," such as alchemy and astrology, from rational scientific thought in the quest for knowledge. [14] In his first major book, The Advancement of Learning, Bacon presents a systematic survey of the extant realms of knowledge, combined with meticulous descriptions of deficiencies, leading to his new classification of knowledge. Bacon divides natural science into physics and metaphysics. The former investigates variable and particular causes, the latter reflects on general and constant ones, for which the term form is used. [15]

Baconian Method

The Baconian method is a methodical observation of facts as a means of studying and interpreting natural phenomena. Francis Bacon formulated this method as a scientific substitute for the prevailing systems of thought, which, in his opinion, relied too often on guessing and the mere citing of authorities to establish truths of science. After first dismissing all prejudices and preconceptions, Bacon’s method, as explained in his book Novum Organum (1620; “New Instrument”), Bacon's method is an example of the application of inductive reasoning but is somewhat complex.

Bacon's scientific methodology can be summarized as follows: 1. The scientist must start with a set of unprejudiced observations; 2. these observations lead infallibly to correct generalizations or axioms; and 3. the test of a correct axiom is that it leads to new discoveries. [16]

The Ethical Dimension in Bacon’s Thought

One should not underestimate the ethical dimension of Bacon's thought. His philosophy of science tries to answer the question of how man can overcome the problems of earthly life resulting from the Fall, thus entering the realm of ethical reflection. The improvement of mankind's problems through philosophy and science emphasizes the building of a better world for mankind, which might happen through the discovering of truths about nature's workings. Bacon studied the nature of good and distinguished various kinds of good. He insisted on the individual's duty to the public and pointed out that private moral self-control and the associated obligations are relevant for behavior and action in society. What we can do might be limited, however, we are obligated to gather our psychological powers and control our passions when dealing with ourselves and with others. We have to apply self-discipline and rational assessment and restrain our passions, in order to lead an active moral life in society. In addition, for Bacon, the acquisition of knowledge does not simply coincide with the possibility of exerting power. Scientific knowledge is a condition for the expansion and development of civilization. Therefore, knowledge and charity cannot be kept separate. [17]

Bacon understood clearly that the human mind doesn’t always reason correctly, and that any approach to scientific knowledge must start with that understanding. Bacon called the wide variety of errors in mental processing the Idols of the Mind. There were four idols: Idols of the Tribe, Idols of the Cave, Idols of the Marketplace, and Idols of the Theatre. According to Bacon, these four idols prevent us from progressing in scientific investigation. [18]

Finally, the view he expresses in his book Nova Atlantis in regard to a utopian society that is carefully organized for the purposes of scientific research and virtuous living holds true for his entire life's work. [19]

Bacon and Shakespeare

A number of Theosophical and other occult writers have published works arguing that Bacon wrote the plays that pass as Shakespeare’s. [20][21]

In fact, there is a lot of research that proves with detailed evidence, how and why Sir Francis Bacon wrote the Shakespeare Plays and Sonnets and, in the meantime, there is a whole website discussing and sharing information about this controversy. [22]

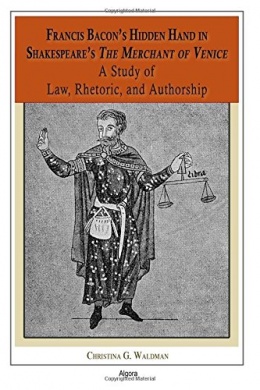

One example is book from 2018, where the author recounts what happened in 1935 at the University of Colorado, when Mark Edwin Andrews, a visiting student, was taking a class on Shakespeare. A chance remark on the relationship between common law and equity in The Merchant of Venice by the professor led him to look more closely at the play which resulted in a paper pointing out that the famous trial scene dramatized the inherent tension between law and equity in the course, that the play influenced the decisive resolution of these competing claims in 1616 when Sir Francis Bacon was asked by the king to make recommendation as to the best course and that the character of Bellario is in some sense Bacon himself. [23]

The Theosophist Charles Leadbeater wrote in regard to the assertion that it was Sir Francis Bacon who authored the works by Shakespeare:

”I recall being present at one of these investigations when in some way Francis Bacon’s work came to be examined. Knowing who Bacon is today, as one of the Adepts, Bishop Leadbeater felt that to investigate Bacon’s affairs clairvoyantly was like a piece of impertinence. But he did note that Bacon wrote the plays that pass as Shakespeare’s. However, what particularly drew my attention at the time was not that fact, which was fairly obvious to me upon the examination of the evidence, but rather something else which Bishop Leadbeater noted on higher planes. If Bacon is Shakespeare, and also if several other works passing under the names of other authors are also from Bacon’s brain, then, there must have been a terrific creative energy in Bacon at the time. Bishop Leadbeater said that, as he watched, it was as if some wonderful ray from a great creative center on the inner planes had converged upon Bacon, so that he threw off one work after another in the way of plays, poems, philosophical theses, etc., without any particular effort. This little glimpse into the power of the creative consciousness behind everything was far more fascinating to me than the solution of the Bacon-Shakespeare problem”. [24]

The Mahatmas and H.P. Blavatsky about Francis Bacon

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky mentions Francis Bacon several times in her writings, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively. Here are two examples:

”They either believe in naught as do the Secularists, or doubt according to the manner of the Agnostics. Remembering the two wise aphorisms by Bacon, the modern-day materialist is thus condemned out of the mouth of the Founder of his own inductive method, as contrasted with the deductive philosophy of Plato, accepted in Theosophy. For does not Bacon tell us that "Philosophy when superficially studied excites doubt; when thoroughly explored it dispels it"; and again, "a little philosophy inclineth man's mind to atheism; but depth of philosophy bringeth man's mind about to religion"?

The logical deduction of the above is, undeniably, that none of our present Darwinians and materialists and their admirers, our critics, could have studied philosophy otherwise than very "superficially." Hence while Theosophists have a legitimate right to the title of philosophers - true "lovers of Wisdom"- their critics and slanderers are at best

PHILOSOPHICULES-the progeny of modern PHILOSOPHISM. [25]

”It is the “Spirit of Light,” the first born of the Eternal pure Element, whose energy (or emanation) is stored in the Sun, the great Life-Giver of the physical world, as the hidden Concealed Spiritual Sun is the Light- and Life-Giver of the Spiritual and Psychic Realms. Bacon was one of the first to strike the keynote of materialism, not only by his inductive method (renovated from ill-digested Aristotle), but by the general tenor of his writings. He inverts the order of mental Evolution when saying that “the first Creation of God was the light of the sense; the last was the light of the reason; and his Sabbath work ever since is the illumination of the Spirit.” It is just the reverse. The light of Spirit is the eternal Sabbath of the mystic or occultist, and he pays little attention to that of mere sense. That which is meant by the allegorical sentence, “Fiat Lux” is, —when esoterically rendered— “Let there be the ‘Sons of Light,’ ” or the noumena of all phenomena. Thus, the Roman Catholics rightly interpret the passage as referring to Angels, and wrongly as meaning Powers created by an anthropomorphic God, whom they personify in the ever thundering and punishing Jehovah.” [26]

Master Koot Hoomi also mentions Francis Bacon in some of his letters:

”The Heavenly White Virgin" (Akas) and others. And it was the illustrious "Chancellor of England and of Nature" — Lord Verulam-Bacon — who having won the name of the Father of Inductive Philosophy, permitted himself to speak of such men [e.g., Gilbert of Colchester, Paracelci, Agrippas] as [..] the "Alchemicians of the Fantastic philosophy."[27]

“Neither our philosophy nor ourselves believe in a God, least of all in one whose pronoun necessitates a capital H. Our philosophy falls under the definition of Hobbes. It is preeminently the science of effects by their causes and of causes by their effects, and since it is also the science of things deduced from first principle, as Bacon defines it, before we admit any such principle, we must know it and have no right to admit even its possibility. Your whole explanation is based upon one solitary admission made simply for argument's sake in October last. You were told that our knowledge was limited to this our solar system: ergo as philosophers who desired to remain worthy of the name, we could not either deny or affirm the existence of what you termed a supreme, omnipotent, intelligent being of some sort beyond the limits of that solar system. But if such an existence is not absolutely impossible, yet unless the uniformity of nature's law breaks at those limits we maintain that it is highly improbable. [28]

”For example: the vices, physical attractions, etc. — say, of a philosopher may result in the birth of a new philosopher, a king, a merchant, a rich Epicurean, or any other personality whose make-up was inevitable from the preponderating proclivities of the being in the next preceding birth. Bacon, for inst: whom a poet called —

"The greatest, wisest, meanest of mankind" —

might reappear in his next incarnation as a greedy money-getter, with extraordinary intellectual capacities. But the moral and spiritual qualities of the previous Bacon would also have to find a field in which their energies could expand themselves. Devachan is such field. Hence — all the great plans of moral reform, of intellectual and spiritual research into abstract principles of nature, all the divine aspirations, would, in devachan come to fruition, and the abstract entity previously known as the great Chancellor would occupy itself in this inner world of its own preparation, living, if not quite what one would call a conscious existence, at least a dream of such realistic vividness that none of the life-realities could ever match it.”[29]

But suppose it is not a question of a Bacon, a Goethe, a Shelley, a Howard, but of some hum-drum person, some colourless, flaxless personality, who never impinged upon the world enough to make himself felt: what then? Simply that his devachanic state is as colourless and feeble as was his personality.” .”[30]

An Occult View of Francis Bacon

In Theosophical literature we can also find opinions that Francis Bacon was not only a great person and a highly spiritual man but an advanced soul. [31] According to Annie Besant, Charles Webster Leadbeater and Alice Bailey, Count de Saint Germain was incarnated over and over again before his birth as Saint-Germaine as various prominent figures in the historical timeline. These figures were all people of supreme importance, and all had a resounding, lasting effect on the history of the world.

“The last survivor of the Royal House of Rakoczi, known as the Comte de S. Germain in the history of the eighteenth century; as Bacon in the seventeenth; as Robertus the monk in the sixteenth, as Hunyadi Janos in the fifteenth; as Christian Rosencreuz in the fourteenth - to take a few of His incarnations - was disciple through these laborious lives and now has achieved Masterhood, the 'Hungarian Adept' of The Occult World, and known to some of us in the Hungarian body ... They live in different countries. . . the Master Rakoczi in Hungary but travelling much..." [32]

Additional resources

- Hall, Manly P. "Francis Bacon, the Concealed Poet." Collected Writings of Manly P. Hall Volume 2: Sages and Seers (Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, Inc., 1959), 92-127.

Notes

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ The Francis Bacon Research Trust. Royal Birth https://www.fbrt.org.uk/bacon/royal-birth/#:~:text=A%20summary%20of%20evidence%20pointing,Nicholas%20and%20Lady%20Anne%20Bacon. Accessed on 10/17/23

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Stave, Sadie. Francis Bacon – Our Shakespeare The American Theosophist, Jan. 1942; 30, 1; Religious Magazine Archive, pg. 9

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Stave, Sadie. Francis Bacon – Our Shakespeare The American Theosophist, Jan. 1942; 30, 1; Religious Magazine Archive, pg. 9

- ↑ Britannica. Francis Bacon. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francis-Bacon-Viscount-Saint-Alban Accessed on 10/19/23

- ↑ Ryan, James. Francis Bacon. Great Neck Publishing, 8/1/2017. Database: MAS Ultra – School Edition. Subscription required

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Goodstein, David and Judith. The Scientific Method http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/44/2/1980Method.htm Accessed on 10/23/23

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Four Idols of Francis Bacon or The New Instrument of Knowledge https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpUMjpnTyf0 Accessed on 10/20/23

- ↑ Francis Bacon. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/ Accessed on 10/15/23

- ↑ Udny, Ernest AN OCCULT VIEW OF LORD BACON The Theosophic Messenger, April 1909, 10, 7

- ↑ Stave, Sadie. Francis Bacon – Our Shakespeare The American Theosophist, Jan. 1942; 30, 1; Religious Magazine Archive, pg. 9

- ↑ SirBacon.Org. https://sirbacon.org/bacon-forum/index.php?/topic/150-baconian-acrostics-anagrams-monograms-secret-signatures-in-the-shakespeare-poems-plays/ Accessed on 10/18/23

- ↑ Waldman, Christina. Francis Bacon’s Hidden Hand in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice”: A Study of Law Rhetoric and Authorship. Algora Publishing, 2018.

- ↑ Jinarajadasa. Occult Investigations. A Description of the Work of Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater. Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, 1938: 40 -41.

- ↑ Blavatsky, Helena. Collected Writings. Vol. 11, page 439. https://www.katinkahesselink.net/blavatsky/articles/v11/y1889_060.htm Accessed on 10/18/23

- ↑ Blavatsky, Helena. The Secret Doctrine. The Sons of Light, vol. I, page 481. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sd-pdf/SecretDoctrineVol1_eBook.pdf accessed on 10/18/23

- ↑ Master Koot Hoomi, Mahatma Letter No. 1, https://theosophy.wiki/en/Mahatma_Letter_No._1 Accessed on 10/23/23

- ↑ Master Koot Humi, Mahatma Letter No. 88. https://theosophy.wiki/en/Mahatma_Letter_No._88 Accessed on 10/23/23

- ↑ Master Koot Humi. Mahatma Letter No. 108. https://theosophy.wiki/en/Mahatma_Letter_No._104 Accessed on 10/23/23

- ↑ Master Koot Humi. Mahatma Letter No. 108. https://theosophy.wiki/en/Mahatma_Letter_No._104 Accessed on 10/23/23

- ↑ Udny, Ernest AN OCCULT VIEW OF LORD BACON The Theosophic Messenger, April 1909, 10, 7

- ↑ Besant, The Masters, (pp. 80-2)