Neoplatonism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''' | '''UNDER CONSTRUCTION'''<br> | ||

'''UNDER CONSTRUCTION'''<br> | |||

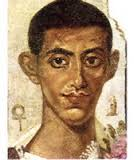

[[File:Neoplatonism.jpg|right|300 px|thumb|]] | |||

Neoplatonism is a philosophical school that reinterpreted and expanded upon the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, particularly focusing on the concept of a single, supreme source of being, goodness, and reality. It argued that the world which we experience is only a copy of an ideal reality which lies beyond the material world. This ideal reality is comprised of three levels and the final level cannot be grasped by philosophy but can only be reached through mystical experience. <ref> National Gallery NG 200. <i>Neoplatonism</i> https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary/neoplatonism. Accessed on 5/5/25</ref> They called the single source of being the "One", who they saw as the source of all other beings and things, which emanate from it in a hierarchy. | |||

Neoplatonism and Theosophy are united by a shared foundation in mystical and philosophical thought. Both explore central themes such as the One, the emanation of the cosmos from a divine source, absolute consciousness, the cyclical nature of existence, the hierarchy of divine beings, and the soul. | |||

==History of Neoplatonism== | |||

Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century AD as a profound evolution of Platonic philosophy, shaped by the rich and diverse intellectual currents of late Hellenistic thought and religious traditions. Rather than representing a rigid system of doctrines, Neoplatonism is best understood as a dynamic lineage of thinkers united by a shared philosophical vision. Central to this vision is the concept of <i>monism</i>—the belief that all of existence ultimately emanates from a single, ineffable source known as the One.<ref>World History Edu. <i>What is Neoplatonism.</i>1/31.25. https://worldhistoryedu.com/what-is-neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/25.25</ref> | |||

=== Ammonius Saccas === | |||

[[File:Ammonius Saccas.png|left|300 px|thumb|Ammonius Saccas]] | |||

The first authentic Neoplatonist was probably <b>Ammonius Saccas</b> (175-250 A.D.), who taught in Alexandria during the last part of the first quarter of the third century. Since he left no writings, his claim to fame rests upon the success of his famous pupils: Plotinus, the two Origens, the philologist Longinus, and Herennius. Although some of them refer to his thought occasionally, it is impossible to determine which of their views were inspired by him. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism.</i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8</ref> | |||

Ammonius was born to devout Christian parents and sent to a Christian school, where he learned about the life of Christ. But he soon noticed striking similarities between the story of Christ and that of Krishna—both born of a virgin, both persecuted by tyrants, both said to have died on a cross. Could these be legends? Were there others like them in different cultures? When he questioned this, the priest insisted there was only one true Christ—all others were false. He was told to believe, but he longed to understand. So Ammonius left the school and set out on a path of sincere inquiry.<ref>GREAT THEOSOPHISTS.<i>Ammonius Saccas</i>THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 2, December, 1936, pages 53-59; number 9 of a 29-part series</ref> | |||

When Ammonius Saccas laid the foundations for that which is called “Neoplatonism”, the philosophical system underwent some changes. He maintained that the great principles of all philosophical and religious truth were to be found equally in all sects; that they differed from each other only in their method of expressing them, and in some opinions of little importance. <ref>Dr. Siemons, Jean-Louis. <i> Theosophical History, Occasional Papers, Vol. III. Ammonius Saccas and his “Eclectic Philosophy” as presented by Alexander Wilder.</i>Theosophical History; Fullerton, Ca. 1994, p. 9</ref> | |||

===Plotinus=== | |||

[[File: Plotinus.jpg|right|300 px|thumb]] | |||

= | Plotinus (203/204 or 205-270 A.D.) was the first notable Neoplatonist. His birthplace is uncertain, since it is given as Lycon by Eunapius and as Lycopolis by Suidas. Plotinus, according to Porphyry, attended the lectures of various professors at Alexandria but was not satisfied until he came upon Ammonius Saccas at the age of 28. <ref>Copleston, S.J. <i>A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 463 </i> https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25</ref>He remained with him for 11 years. At the end of that time Plotinus determined to visit Persia and India so that he could study the Eastern philosophies at first hand. At the age of thirty-nine he joined the army of the Emperor Gordian and went with him to the Far East. After the destruction of Gordian's army Plotinus returned to Antioch and finally went to Rome during the reign of the Emperor Philip. <ref>From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i>Plotinus</i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)</ref> | ||

He ended up in Rome around 240 A.D. and obtained great renown and was respected by all. It is said that during the 26 years he lived in Rome he did not have a single enemy. He was often approached for help and advice, took in orphaned children acting as their guardian, and led a deeply spiritual life. Even the Emperor Gallienus, one of the greatest villains respected and honored him. <ref> Dr. Hartmann, Franz. <i>In the Pronaos of the Temple of Wisdom</i>. Chapter 2. 1890. https://sacred-texts.com/sro/ptw/ptw04.htm Accessed on 4/22/25</ref> <ref>Copleston, S.J. <i>A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 464 </i> https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25</ref> | |||

In a | In Rome he founded a school of philosophy. At first, his instruction was entirely oral, until his most talented pupil, Porphyry, persuaded him to commit his seminars to the page. <ref>Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25</ref> Thus, he began to write when he was fifty years old and during the following ten years wrote twenty-one books which were circulated among his friends and pupils. Before his death, Plotinus had written fifty-four books dealing with physics, ethics, psychology and philosophy. Plotinus was thoroughly conversant with the doctrines of the Stoics and Peripatetics and found it useful to employ these familiar ideas in his writings. There was no geometrical, arithmetical, mechanical, optical or musical theorem with which he was not acquainted, although he does not seem to have applied these sciences to "practical" purposes. <ref>From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i>Plotinus</i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)</ref> | ||

Plotinus died at the age of sixty-six. It is said, that at the moment of his death a Dragon, or Serpent, glided through a hole in the wall and disappeared -- a fact highly suggestive to the student of symbolism. In later years Porphyry, his devoted pupil, summed up Plotinus' life in these words: | |||

<blockquote>”He left the orb of light solely for the benefit of mankind. He came as a guide to the few who are born with a divine destiny and are struggling to gain the lost region of light, but know not how to break the fetters by which they are detained; who are impatient to leave the obscure cavern of sense, where all is delusion and shadow, and to ascend to the realms of intellect, where all is substance and reality. <ref>From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i>Plotinus</i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)</ref></blockquote> | |||

After Plotinus’ death, Porphyry edited and published his writings, arranging them in a collection of six books consisting of nine essays each (the so-called “Enneads” or “nines”). <ref>Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25</ref> | |||

===Malchus Porphyry=== | |||

[[File: Porphyry.jpg|right|300 px|thumb|Malchus Prphyry]] | |||

The real name of Porphyry (232-c.304 A.D.), a native of Tyre, was Melek (a king). This name was rendered by Longinus into <i>Porphyrius</i> (the royal purple), as its proper equivalent, and so he has come down through history under the name of Porphyry. While there is no doubt that Porphyry had Jewish blood in his veins, it is apparent that he never followed the Hebrew doctrines but was thoroughly Hellenized and a true "pagan." <ref> GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i> IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES </i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.</ref> | |||

Porphyry, the editor of Plotinus's <i>Enneads</i>, stands at the origin of a new evolution of Neoplatonism: the infusion into it of the Chaldean Oracles. This is a collection of texts from the second to third centuries CE, whose redaction has been attributed (uncertainly) to Julian the Theurgist. One finds in them, in an oracular form, a theoretical content very much influenced by Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. But this metaphysical content mingles with ritual and liturgical prescriptions, presented as so many ways to reach the divine. | |||

The Chaldean Oracles thus precipitate both a theological and a theurgical turn in Neoplatonism. The Oracles play the role of a revealed text, so much so that one may see in them the "Bible" of post-Plotinian Neoplatonists. | |||

Thus, like Plato, Plotinus also suffered the fate of having his philosophy altered by his disciples. | |||

Porphyry and others tried to conciliate the content of the Oracles with the doctrines of Plato and Plotinus. This theological turn is also a theurgical one, for now rituals aiming at union with the divine come to the fore. In short, a new path to the mystical experience is introduced, distinct from the inner conversion prescribed by Plotinus. Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude; rather, it is a kind of “technique of passivity,” whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. <ref>Aubry, Gwenaelle. <i>Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism. </i> In: <i>The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism. </i> Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48</ref> | |||

=== Amelius Gentilianus=== | |||

Amelius Gentilianus was a Neoplatonist philosopher and writer of the second half of the 3rd century. He began attending the lectures of Plotinus in the third year after Plotinus came to Rome ><ref>Porphyry.<i>Vita Plotini</i>. p.3. Access through subscription. </ref> | |||

and stayed with him for more than twenty years, until 269, when he retired to Apamea in Syrica, the native place of Numenius, a Greek philosopher. He was responsible for the conversion of Porphyry to Neoplatonism. His principle literary work was a treatise in forty books, arguing against the claim that Numenius should be considered the original author of the doctrines of Plotinus. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism.</i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8</ref><ref>Porphyry.<i>Vita Plotini</i>. 16-18. Access through subscription. </ref> | |||

===Iamblichus=== | |||

[[File:Iamblichus.jpg|left|300 px|thumb|Iamblichus]] | |||

Iamblichus (ca. 242–ca. 325 A.D.) was born in Chalsis, in Coele-Syria, at about the middle of the third century. Based on fragments of his life which have been collected by impartial historians, he was a man of great culture and learning, and renowned for his charity and self-denial. His mind was deeply impregnated with Pythagorean doctrines, and in his famous biography of Pythagoras he has set forth the philosophical, ethical and scientific teachings of the Sage of Samos in full detail. He was also a profound student of the Egyptian Mysteries and expressed his determination to make public what hitherto had been taught only in the Mystery Schools under the greatest secrecy. <ref> GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i> IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES </i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.</ref> | |||

He exerted considerable influence among later philosophers belonging to the same tradition, such as Proclus, Damascius, and Simplicius. His work as a Pagan theologian and exegete earned him high praise and made a decisive contribution to the transformation of Plotinian metaphysics into the full-fledged system of the fifth-century school of Athens, at that time the major school of philosophy, along with the one in Alexandria. His harsh critique of Plotinus’ philosophical tenets is linked to his pessimistic outlook on the condition of the human soul, as well as to his advocacy of salvation by ritual means, known as “theurgy”. <ref>Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25</ref> | |||

In fact, he advocated theurgy as the exclusive path to salvation. This internal scission of Neoplatonism partly rests on a disagreement as to the nature of the soul. Iamblichus believed, as did Aristotle, that the soul is nothing else than the life of the body. He refused to accept the idea of a separate soul whose power one would have to activate in oneself. | |||

Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude. It is a kind of "technique of passivity," whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. <ref>Aubry, Gwenaelle. <i>Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism.</i> In: <i>The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism.</i> Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48</ref> | |||

Iamblichus focused more closely than Plotinus on the soul’s indwelling within the body and on the actions it performs alongside it. In what remains of his treatise <i>On the Soul</i>, he reviews all sorts of historical theses about the composition, powers and activities of the soul, and does not hesitate to engage his Neoplatonic predecessors. | |||

He also wrote a whole treatise <i>On virtues</i>, which is lost but whose content can be inferred from later sources. In addition to this, references to ethics and politics can be gathered from his extant works. <ref>Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25</ref> | |||

===Proclus=== | |||

[[File: Proclus,_Platonic_Theology.jpg|right|300 px|thumb|Proclus-Platonic Theology]] | |||

Proclus of Athens (412–485 C.E.) was the most authoritative philosopher of late antiquity and played a crucial role in the transmission of Platonic philosophy from antiquity to the Middle Ages. For almost fifty years, he was head of the Platonic ‘Academy’ in Athens. He was an exceptionally productive writer and composed commentaries on Aristotle, Euclid and Plato, and systematic treatises in all disciplines of philosophy. Proclus had a lasting influence on the development of the late Neoplatonic schools not only in Athens, but also in Alexandria, where his student Ammonius became the head of the school. <ref>Proclus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/proclus/. Accessed on 4/30/25</ref> | |||

Like Plotinus, he taught that man's ultimate goal is union with the Ultimate but added that theurgy can be an aid higher than the practice of dialectics. He was highly influenced by Plato's <i>Timaeus</i> and once stated that if it were in his power to do so he would withdraw all books from human knowledge except the <i>Timaeus</i> and the <i>Chaldean Oracles</i>. | |||

In two of his works, <i>Elements of Theology</i> and <i>Plato's Theology</i>, he provided elaborate explanations of Neoplatonism. Both were fairly well circulated and had no small influence upon Byzantine, Arabic, and early medieval Latin Christian thought. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism. </i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11</ref> | |||

== The | In his <i>Lectures on the History of Philosophy</i>, in the chapter on Alexandrian Philosophy, Hegel said that “in Proclus we have the culminating point of the Neo-Platonic philosophy; this method in philosophy is carried into later times, continuing even through the whole of the Middle Ages. […] Although the Neo-Platonic school ceased to exist outwardly, ideas of the Neo-Platonists, and specially the philosophy of Proclus, were long maintained and preserved in the Church.” <ref>Proclus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/proclus/. Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | ||

===Hypatia === | |||

[[File:The Death of Hypatia.jpg|left|300px|thumb|"Death of the philosopher Hypatia, in Alexandria" from Vies des savants illustres, depuis l'antiquité jusqu'au dix-neuvième siècle, 1866, by Louis Figuier]] | |||

Hypatia (355 CE – 415 CE) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher. She was living in Athens when she first became acquainted with the Neoplatonic school. Later she moved to Alexandria where she became the head of the school. She was a popular teacher and lecturer on astronomy and philosophical topics of a less-specialist nature, attracting many loyal students and large audiences. She is the earliest female mathematician of whose life and work reasonably detailed knowledge exists.<ref>Britannica. <i>Hypatia.</> https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hypatia. Accessed on 5/5/25</ref> | |||

Hypatia brought Egypt nearer to an understanding of its ancient Mysteries than it had been for thousands of years. Her knowledge of theurgy restored the practical value of the Mysteries and completed the work commenced by Iamblichus. Continuing the work of Ammonius Saccas, she showed the similarity between all religions and the identity of their source.” <ref>http://plato2051.tripod.com/hypatia_of_alexandria.htm</ref> | |||

Under the leadership of this astonishing woman Neoplatonism thrived. She publicly debated and analyzed the metaphysical allegories from which Christianity had pirated its dogmas and repeatedly and publicly embarrassed the new church. Despite her scholarly achievements, Hypatia faced growing hostility as Christianity gained dominance in Alexandria and the Catholic Church had ways of dealing with opposition, especially from women who obviously had not learned the rightful place of women according to the Catholic Church. | |||

One afternoon in 414 a group of Cyril’s monks, led by Peter the Reader, descended on Hypatia as she left the Museum where she had just finished teaching a class. They stripped her naked and dragged her to a nearby church where at the altar of the church Peter the Reader struck her dead. The crowd then dragged her dead body into the street where they scraped the flesh from her bones with oyster shells and burned what remained in a bonfire.<ref>GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. <i>HYPATIA: THE LAST OF THE NEOPLATONISTS.</i> THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, March, 1937. Pages 197-207; Number 12 of a 29-part series.</ref> | |||

=== Late Neoplatonism and Christian Adaptations=== | |||

[[File: Damascius_(462-538).png|right|300 px|thumb|Damascius]] | |||

Proclus was indirectly the source of many elements of medieval scholastic Christian thought, since the very widely circulated Christian documents, <i>Divine Names</i> and <i>Mystical Theology</i>, purportedly written by Dionysius the Areopagite, a disciple of St. Paul, but actually written by some unknown monk in the late fifth century, were in fact adaptations of Proclus' thought. | |||

Proclus' successor was Marinus, a Palestinian Jew. It is possible that he was the source of the Neoplatonism that got into the medieval Jewish tradition, if not of the mysticism of | |||

"The Book of Creation," the Sefer Yezirah. Athenian Neoplatonism, i.e., the Academy, lasted for about forty years after Proclus, until it was shut down by decree of Justinian I in 529. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism. </i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11-12</ref> | |||

The last Siáoxos was Damascius (480-550 A.D.) whose work opened the way to genuine mysticism by his insistence that human speculation can never attain to the ineffable first principle. Unwilling even to call this principle by “the One”, Damascius declared that men cannot adequately describe its relation to derived reality. This first principle is beyond the reach of human thought and language and is utterly outside the hierarchy of reality. Because it is outside, everything, and particularly the soul of man, can participate in it directly and without intermediary, though in an unspeakably mysterious way. Though a pagan, Damascius thus pointed the way to later Christian mystics.<ref> Britannica. <i>Dasmcius.</i> https://www.britannica.com/biography/Damascius | |||

Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

Neoplatonism continued to flourish in Rome and Alexandria during the time of the late Academy in Athens, but no notable ideological changes occurred in it in either location. It continued in Rome until the latter part of the sixth century. | |||

Among its products was the Neoplatonic Christian Mariu Victorinus (c. 350), whose Latin translations of Neoplatonic literature were read by Augustine and Boethius (c. 470-535). The Alexandrian School of Neoplatonism began in the middle of the fourth century and appears to have maintained strong connections with Athenian Neoplatonism at this time, including exchanging professors. Generally, the Alexandrian Neoplatonic professors remained closer to the thought of Plato and the Middle Platonists and did not enter into metaphysical speculations, theology, and theurgy, as did the Athenians, and they displayed a more conciliatory attitude toward Christianity. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism. </i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11-12</ref> | |||

==Neoplatonism and Theosophy== | |||

[[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky]] would have called Neoplatonists Theosophists. In ''The Keys to Theosophy'' she states: “The name Theosophy dates from the third century of our era and began with [[Ammonius Saccas]] and his disciples who started the Eclectic Theosophical system.” “They (Neoplatonists) were the Theosophists of early centuries."<ref>Mills, Joy.'' The Key to Theosophy'': H. P. Blavatsky : an Abridgement. Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill. 2013. P. 1</ref> In fact, Ammonius Saccas was the first to use the term "theosophy," which means "divine wisdom," combining "god" or "divine" (theos) and wisdom (sophia). | |||

In <i>Isis Unveiled</i> she wrote that<blockquote>“the Platonic philosophy is the most elaborate compend of the abstruse systems of old India, that can alone afford us this middle ground. Although twenty-two and a quarter centuries have elapsed since the death of Plato, the great minds of the world are still occupied with his writings. He was, in the fullest sense of the word, the world's interpreter. And the greatest philosopher of the pre-Christian era mirrored faithfully in his works the spiritualism of the Vedic philosophers who lived thousands of years before himself, and its metaphysical expression. Vyasa, Djeminy, Kapila, Vrihaspati, Sumati, and so many others, will be found to have transmitted their indelible imprint through the intervening centuries upon Plato and his school. Thus, is warranted the inference that to Plato and the ancient Hindu sages was alike revealed the same wisdom. So, surviving the shock of time, what can this wisdom be but divine and eternal?” <ref>Blavatsky, Helena. <i>Isis Unveiled</i> Page 15. https://www.theosophy-ult.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/isis-unveiled-vol1.pdf Accessed on 4/22/25</ref></blockquote> | |||

There are a lot of overlaps between Neo-Platonism and Theosophy. Both teach a process of emanation from the divine source into differentiated forms, and a return journey to unity and emphasize the soul’s <i>spiritual evolution</i> and its eventual <i>return to Source</i> through inner awakening. Both traditions see <i>gnosis or higher knowledge</i> as the means to liberation, and reason as a lower step toward it; they emphasize a <i>hierarchical cosmos</i> in which beings serve as <i>bridges to the divine</i> as well as <i>spiritual discipline and transformation</i>, not only intellectual belief. Let’s look at some comparative quotes: | |||

<table class="wikitable"> | |||

<caption><p style="font-size:25px;"> Neoplatonism and Theosophy: Comparative Quotes </p></caption> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th><b>Topic</b></th> | |||

<th><b>Plotinus</b></th> | |||

<th><b>Proclus</b></th> | |||

<th><b>H.P. Blavatsky</b></th> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td> <b>The One/Absolute</b> </td> | |||

<td>“The One is beyond all multiplicity and diversity."</td> | |||

<td>"Every good tends to unify what participates it; and all unification is a good; and the Good is identical with the | |||

One."</td> | |||

<td>"It is 'Be-ness' rather than Being... an Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable PRINCIPLE."</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td> <b>Soul's Return / Union </b></td> | |||

<td>"The soul is inherently divine and possesses the potential for union with the One." | |||

</td> | |||

<td>"Everything is overflowing with Gods."</td> | |||

<td>“The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul... and the obligatory pilgrimage for every Soul."</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td> <b>Knowledge/Intuition</b> </td> | |||

<td> You can only apprehend the Infinite by a faculty that is superior to reason."</td> | |||

<td>"Wherever there is number, there is beauty."</td> | |||

<td>"Everything in the Universe... is conscious: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception."</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td> <b>Spiritual Practice / Transformation</b></td> | |||

<td>“The mystical experience is a flight of the alone to the alone."</td> | |||

<td>"This, therefore, is mathematics: she reminds you of the invisible form of the soul... she awakens the mind and purifies the intellect."</td> | |||

<td>"Everything in the Universe... is conscious: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception."</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table><ref> Reece, Gwendolyn. <i>Neoplatonism: The Beginning of Theosophy in the West</i> Four week course for the Online-School of Theosophy. Available at the end of 2025</ref> | |||

'''UNDER CONSTRUCTION'''<br> | |||

'''UNDER CONSTRUCTION'''<br> | |||

==Western Renaissance and Modern Neo-Platonism== | |||

[[File: Henry_More.jpg|right|300 px|thumb|Henry More of the Cambridge Platonist School]] | |||

===Western Renaissance=== | |||

<b>George Gemistos Pletho</b> (1355-1452), a prominent Byzantine scholar, is a central figure in the revival and transmission of Neoplatonism in the West, particularly during the Renaissance. Concerned more with the advancement of Neoplatonic philosophy than with religious questions, Plethon delivered to the Florentine humanists at the Council of Ferrara–Florence his treatise “On the Difference Between Ristotle and Plato.” This work fired the humanists with a new interest in Plato (who had been ignored in the West during the Middle Ages because of the preoccupation with Aristotle) and inspired Cosimo de’Medici with the project of founding the Platonic Academy of Florence. <ref>Britannica. <i> George Gemistus Plethon</i> https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Gemistus-Plethon. Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

The work of the humanist Platonist [[Marsilio Ficino]] (1433-1499), who translated Plotinus' writings into Latin in 1484-1486 and then commented on them from the perspective of his Christian Neoplatonism, was groundbreaking. His work sparked the Florentine Platonic Renaissance, shaping European intellectual life for more than two centuries.<ref> Marsilio Ficino, Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marsilio-Ficino, Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

Giovanni [[Pico della Mirandola]] (1463–1494) was another Neoplatonist during the Italian Renaissance. He could speak and write Latin and Greek and had knowledge on Hebrew and Arabic. The pope banned his works because they were viewed as heretical – unlike Ficino, who managed to stay on the right side of the church. He was introduced to the Hebrew Kabbala and became the first Christian scholar to use Kabbalistic doctrine in support of Christian theology. <ref>Britannica. <i>Giovanni Pico della Mirandola</i> https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giovanni-Pico-della-Mirandola-conte-di-Concordia | |||

Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

===The Cambridge Platonists=== | |||

Some elements of Florentine Neoplatonism were imported into England in the 1490s by <i>John Colet</i> (1466-1519), who was then Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Colet carried on correspondence with Ficino, wrote a commentary on the writing of pseudo-Dyonysius, and paved the way for the 17th century Neoplatonists known as the Cambridge Platonists. <ref>Harris, Baine. <i>The Significance of Neoplatonism.</i> International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 18</ref> | |||

The Cambridge Platonists represent the most important school of Platonic philosophers between the Italian Renaissance and the Romantic Age. They were a group of English seventeenth-century thinkers associated with the University of Cambridge. The most important philosophers among them were Henry More (1614–1687) and Ralph Cudworth (1617–1688), both fellows of Christ’s College, Cambridge. The group also included Benjamin Whichcote (1609–1683), Peter Sterry (1613–1672), John Smith (1618–1652), Nathaniel Culverwell (1619–1651), and John Worthington (1618–1671). All of them studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, apart from More who studied at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where Cudworth was later appointed Master. | |||

They only came to be referred to as Platonists in the eighteenth century. But in so far as they all held the philosophy of Plato and Plotinus in high regard, and adopted principles of Platonist epistemology and metaphysics, the designation ‘Platonist’ is apt.<ref>The Cambridge Platonists. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cambridge-platonists/ Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

==Theosophists and the Neoplatonic Tradition== | |||

[[Alexander Wilder]] (1823-1909) was an American physician and Neoplatonist scholar, and a prominent early member of the Theosophical Society. He wrote the pamphlet <i>New Platonism and Alchemy: A Sketch of the Doctrines and Principal Teachers of Eclectic or Alexandrian School</i>. It was this brief work of some 30 pages that provided Madame Blavatksy with the necessary informatiuon on Ammonius Saccas and his disciples. <ref>Dr. Siemons, Jean-Louis. <i> Theosophical History, Occasional Papers, Vol. III. Ammonius Saccas and his “Eclectic Philosophy” as presented by Alexander Wilder.</i>Theosophical History; Fullerton, Ca. 1994, Foreword.</ref> | |||

[[Thomas Moore Johnson]] (1851-1919) was an attorney, collector, and student of philosophy in Osceola, Missouri. Though his formal training in philosophy was sparse, his consummate philosophical interests led him to become a foremost lay authority on Plato and the Neoplatonists. He translated Neoplatonist works such as Iamblichus’ <i>Exhortation to the Study of Philosophy</i> (1907), Proclus’ <i>Metaphysical Elements</i> (1909) and <i>Opuscula Platonia (1908)</i>. He edited the periodical [[The Platonist]], which was subtitled "An exponent of the philosophic truth, and devoted chiefly to the dissemination of the Platonic philosophy in all its phases." Published from 1881 until 1888, it was superceded by Bibliotheca Platonica.<ref>University of Missouri. <i>Thomas Moore Johnson Collection of Philosophy.</i> https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/collections/show/6 Accessed on 5/6/25</ref> | |||

==Books== | ==Books== | ||

| Line 96: | Line 196: | ||

Harris, R B. The Significance of Neoplatonism. Norfolk, Va: International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University, 1976. Print. | Harris, R B. The Significance of Neoplatonism. Norfolk, Va: International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University, 1976. Print. | ||

==Online resources== | ==Online resources== | ||

| Line 102: | Line 201: | ||

===Articles=== | ===Articles=== | ||

* [http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/books/wil-plat/npa-1.htm# The Eclectic Philosophy] by Alexander Wilder. | * [http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/books/wil-plat/npa-1.htm# The Eclectic Philosophy] by Alexander Wilder. | ||

* [https://www.theosophy.world/encyclopedia/neoplatonism Neoplatonism] | * [https://www.theosophy.world/encyclopedia/neoplatonism Neoplatonism] in Theosophy World. | ||

* [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ Plotinus] in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/ Plotinus] in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. | ||

* [http://www.digital-brilliance.com/themes/theurgy.php Theurgy and Magic] in Hermetic Kabbalah website. | * [http://www.digital-brilliance.com/themes/theurgy.php Theurgy and Magic] in Hermetic Kabbalah website. | ||

| Line 111: | Line 210: | ||

===Video=== | ===Video=== | ||

* '''''Turning-Points for the West: From Pythagoras and Plato through Gnosticism and Neoplatonism''''' by Stephan Hoeller and Tony Lysy | * '''''Turning-Points for the West: From Pythagoras and Plato through Gnosticism and Neoplatonism''''' by Stephan Hoeller and Tony Lysy, presented on September 11, 2004 at the Theosophical Society in America. | ||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= | ** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=LsmYIePbGm0 Part 1]. | ||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= | ** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zSns4uWpQFU Part 2]. | ||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= | ** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EwjO0cQaKS4 Part 3]. | ||

* '''''All About Platonism''''' series by Mindy Mandell. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k2ooRgdL-So&t=7s Transformation]. Added January 31, 2022. 28 minutes. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Emgjj9KkY5k Things in Themselves]. Added December 6, 2021. 27 minutes. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBkYHqwi0ms Dialectic]. Added January 17, 2022. 17 minutes. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEZPEG81aHw Menexenus]. Added April 12, 2021. 24 minutes. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Wb5QBXiV1o Purification]. Added February 7, 2022. 29 minutes. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVjHW_g7ubA Plotinus 1:6 Beauty]. Added January 24, 2022. 27 minutes. Discusses [[Neoplatonism]]. | |||

** [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyVuRh7S3hw 12 Gods of the Phaedrus]. Added January 10, 2022. 13 minutes. | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

Latest revision as of 19:26, 6 May 2025

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Neoplatonism is a philosophical school that reinterpreted and expanded upon the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, particularly focusing on the concept of a single, supreme source of being, goodness, and reality. It argued that the world which we experience is only a copy of an ideal reality which lies beyond the material world. This ideal reality is comprised of three levels and the final level cannot be grasped by philosophy but can only be reached through mystical experience. [1] They called the single source of being the "One", who they saw as the source of all other beings and things, which emanate from it in a hierarchy.

Neoplatonism and Theosophy are united by a shared foundation in mystical and philosophical thought. Both explore central themes such as the One, the emanation of the cosmos from a divine source, absolute consciousness, the cyclical nature of existence, the hierarchy of divine beings, and the soul.

History of Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century AD as a profound evolution of Platonic philosophy, shaped by the rich and diverse intellectual currents of late Hellenistic thought and religious traditions. Rather than representing a rigid system of doctrines, Neoplatonism is best understood as a dynamic lineage of thinkers united by a shared philosophical vision. Central to this vision is the concept of monism—the belief that all of existence ultimately emanates from a single, ineffable source known as the One.[2]

Ammonius Saccas

The first authentic Neoplatonist was probably Ammonius Saccas (175-250 A.D.), who taught in Alexandria during the last part of the first quarter of the third century. Since he left no writings, his claim to fame rests upon the success of his famous pupils: Plotinus, the two Origens, the philologist Longinus, and Herennius. Although some of them refer to his thought occasionally, it is impossible to determine which of their views were inspired by him. [3]

Ammonius was born to devout Christian parents and sent to a Christian school, where he learned about the life of Christ. But he soon noticed striking similarities between the story of Christ and that of Krishna—both born of a virgin, both persecuted by tyrants, both said to have died on a cross. Could these be legends? Were there others like them in different cultures? When he questioned this, the priest insisted there was only one true Christ—all others were false. He was told to believe, but he longed to understand. So Ammonius left the school and set out on a path of sincere inquiry.[4]

When Ammonius Saccas laid the foundations for that which is called “Neoplatonism”, the philosophical system underwent some changes. He maintained that the great principles of all philosophical and religious truth were to be found equally in all sects; that they differed from each other only in their method of expressing them, and in some opinions of little importance. [5]

Plotinus

Plotinus (203/204 or 205-270 A.D.) was the first notable Neoplatonist. His birthplace is uncertain, since it is given as Lycon by Eunapius and as Lycopolis by Suidas. Plotinus, according to Porphyry, attended the lectures of various professors at Alexandria but was not satisfied until he came upon Ammonius Saccas at the age of 28. [6]He remained with him for 11 years. At the end of that time Plotinus determined to visit Persia and India so that he could study the Eastern philosophies at first hand. At the age of thirty-nine he joined the army of the Emperor Gordian and went with him to the Far East. After the destruction of Gordian's army Plotinus returned to Antioch and finally went to Rome during the reign of the Emperor Philip. [7]

He ended up in Rome around 240 A.D. and obtained great renown and was respected by all. It is said that during the 26 years he lived in Rome he did not have a single enemy. He was often approached for help and advice, took in orphaned children acting as their guardian, and led a deeply spiritual life. Even the Emperor Gallienus, one of the greatest villains respected and honored him. [8] [9]

In Rome he founded a school of philosophy. At first, his instruction was entirely oral, until his most talented pupil, Porphyry, persuaded him to commit his seminars to the page. [10] Thus, he began to write when he was fifty years old and during the following ten years wrote twenty-one books which were circulated among his friends and pupils. Before his death, Plotinus had written fifty-four books dealing with physics, ethics, psychology and philosophy. Plotinus was thoroughly conversant with the doctrines of the Stoics and Peripatetics and found it useful to employ these familiar ideas in his writings. There was no geometrical, arithmetical, mechanical, optical or musical theorem with which he was not acquainted, although he does not seem to have applied these sciences to "practical" purposes. [11] Plotinus died at the age of sixty-six. It is said, that at the moment of his death a Dragon, or Serpent, glided through a hole in the wall and disappeared -- a fact highly suggestive to the student of symbolism. In later years Porphyry, his devoted pupil, summed up Plotinus' life in these words:

”He left the orb of light solely for the benefit of mankind. He came as a guide to the few who are born with a divine destiny and are struggling to gain the lost region of light, but know not how to break the fetters by which they are detained; who are impatient to leave the obscure cavern of sense, where all is delusion and shadow, and to ascend to the realms of intellect, where all is substance and reality. [12]

After Plotinus’ death, Porphyry edited and published his writings, arranging them in a collection of six books consisting of nine essays each (the so-called “Enneads” or “nines”). [13]

Malchus Porphyry

The real name of Porphyry (232-c.304 A.D.), a native of Tyre, was Melek (a king). This name was rendered by Longinus into Porphyrius (the royal purple), as its proper equivalent, and so he has come down through history under the name of Porphyry. While there is no doubt that Porphyry had Jewish blood in his veins, it is apparent that he never followed the Hebrew doctrines but was thoroughly Hellenized and a true "pagan." [14] Porphyry, the editor of Plotinus's Enneads, stands at the origin of a new evolution of Neoplatonism: the infusion into it of the Chaldean Oracles. This is a collection of texts from the second to third centuries CE, whose redaction has been attributed (uncertainly) to Julian the Theurgist. One finds in them, in an oracular form, a theoretical content very much influenced by Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. But this metaphysical content mingles with ritual and liturgical prescriptions, presented as so many ways to reach the divine.

The Chaldean Oracles thus precipitate both a theological and a theurgical turn in Neoplatonism. The Oracles play the role of a revealed text, so much so that one may see in them the "Bible" of post-Plotinian Neoplatonists.

Thus, like Plato, Plotinus also suffered the fate of having his philosophy altered by his disciples.

Porphyry and others tried to conciliate the content of the Oracles with the doctrines of Plato and Plotinus. This theological turn is also a theurgical one, for now rituals aiming at union with the divine come to the fore. In short, a new path to the mystical experience is introduced, distinct from the inner conversion prescribed by Plotinus. Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude; rather, it is a kind of “technique of passivity,” whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. [15]

Amelius Gentilianus

Amelius Gentilianus was a Neoplatonist philosopher and writer of the second half of the 3rd century. He began attending the lectures of Plotinus in the third year after Plotinus came to Rome >[16] and stayed with him for more than twenty years, until 269, when he retired to Apamea in Syrica, the native place of Numenius, a Greek philosopher. He was responsible for the conversion of Porphyry to Neoplatonism. His principle literary work was a treatise in forty books, arguing against the claim that Numenius should be considered the original author of the doctrines of Plotinus. [17][18]

Iamblichus

Iamblichus (ca. 242–ca. 325 A.D.) was born in Chalsis, in Coele-Syria, at about the middle of the third century. Based on fragments of his life which have been collected by impartial historians, he was a man of great culture and learning, and renowned for his charity and self-denial. His mind was deeply impregnated with Pythagorean doctrines, and in his famous biography of Pythagoras he has set forth the philosophical, ethical and scientific teachings of the Sage of Samos in full detail. He was also a profound student of the Egyptian Mysteries and expressed his determination to make public what hitherto had been taught only in the Mystery Schools under the greatest secrecy. [19]

He exerted considerable influence among later philosophers belonging to the same tradition, such as Proclus, Damascius, and Simplicius. His work as a Pagan theologian and exegete earned him high praise and made a decisive contribution to the transformation of Plotinian metaphysics into the full-fledged system of the fifth-century school of Athens, at that time the major school of philosophy, along with the one in Alexandria. His harsh critique of Plotinus’ philosophical tenets is linked to his pessimistic outlook on the condition of the human soul, as well as to his advocacy of salvation by ritual means, known as “theurgy”. [20]

In fact, he advocated theurgy as the exclusive path to salvation. This internal scission of Neoplatonism partly rests on a disagreement as to the nature of the soul. Iamblichus believed, as did Aristotle, that the soul is nothing else than the life of the body. He refused to accept the idea of a separate soul whose power one would have to activate in oneself.

Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude. It is a kind of "technique of passivity," whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. [21]

Iamblichus focused more closely than Plotinus on the soul’s indwelling within the body and on the actions it performs alongside it. In what remains of his treatise On the Soul, he reviews all sorts of historical theses about the composition, powers and activities of the soul, and does not hesitate to engage his Neoplatonic predecessors.

He also wrote a whole treatise On virtues, which is lost but whose content can be inferred from later sources. In addition to this, references to ethics and politics can be gathered from his extant works. [22]

Proclus

Proclus of Athens (412–485 C.E.) was the most authoritative philosopher of late antiquity and played a crucial role in the transmission of Platonic philosophy from antiquity to the Middle Ages. For almost fifty years, he was head of the Platonic ‘Academy’ in Athens. He was an exceptionally productive writer and composed commentaries on Aristotle, Euclid and Plato, and systematic treatises in all disciplines of philosophy. Proclus had a lasting influence on the development of the late Neoplatonic schools not only in Athens, but also in Alexandria, where his student Ammonius became the head of the school. [23]

Like Plotinus, he taught that man's ultimate goal is union with the Ultimate but added that theurgy can be an aid higher than the practice of dialectics. He was highly influenced by Plato's Timaeus and once stated that if it were in his power to do so he would withdraw all books from human knowledge except the Timaeus and the Chaldean Oracles.

In two of his works, Elements of Theology and Plato's Theology, he provided elaborate explanations of Neoplatonism. Both were fairly well circulated and had no small influence upon Byzantine, Arabic, and early medieval Latin Christian thought. [24]

In his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, in the chapter on Alexandrian Philosophy, Hegel said that “in Proclus we have the culminating point of the Neo-Platonic philosophy; this method in philosophy is carried into later times, continuing even through the whole of the Middle Ages. […] Although the Neo-Platonic school ceased to exist outwardly, ideas of the Neo-Platonists, and specially the philosophy of Proclus, were long maintained and preserved in the Church.” [25]

Hypatia

Hypatia (355 CE – 415 CE) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher. She was living in Athens when she first became acquainted with the Neoplatonic school. Later she moved to Alexandria where she became the head of the school. She was a popular teacher and lecturer on astronomy and philosophical topics of a less-specialist nature, attracting many loyal students and large audiences. She is the earliest female mathematician of whose life and work reasonably detailed knowledge exists.[26]

Hypatia brought Egypt nearer to an understanding of its ancient Mysteries than it had been for thousands of years. Her knowledge of theurgy restored the practical value of the Mysteries and completed the work commenced by Iamblichus. Continuing the work of Ammonius Saccas, she showed the similarity between all religions and the identity of their source.” [27] Under the leadership of this astonishing woman Neoplatonism thrived. She publicly debated and analyzed the metaphysical allegories from which Christianity had pirated its dogmas and repeatedly and publicly embarrassed the new church. Despite her scholarly achievements, Hypatia faced growing hostility as Christianity gained dominance in Alexandria and the Catholic Church had ways of dealing with opposition, especially from women who obviously had not learned the rightful place of women according to the Catholic Church.

One afternoon in 414 a group of Cyril’s monks, led by Peter the Reader, descended on Hypatia as she left the Museum where she had just finished teaching a class. They stripped her naked and dragged her to a nearby church where at the altar of the church Peter the Reader struck her dead. The crowd then dragged her dead body into the street where they scraped the flesh from her bones with oyster shells and burned what remained in a bonfire.[28]

Late Neoplatonism and Christian Adaptations

Proclus was indirectly the source of many elements of medieval scholastic Christian thought, since the very widely circulated Christian documents, Divine Names and Mystical Theology, purportedly written by Dionysius the Areopagite, a disciple of St. Paul, but actually written by some unknown monk in the late fifth century, were in fact adaptations of Proclus' thought.

Proclus' successor was Marinus, a Palestinian Jew. It is possible that he was the source of the Neoplatonism that got into the medieval Jewish tradition, if not of the mysticism of "The Book of Creation," the Sefer Yezirah. Athenian Neoplatonism, i.e., the Academy, lasted for about forty years after Proclus, until it was shut down by decree of Justinian I in 529. [29]

The last Siáoxos was Damascius (480-550 A.D.) whose work opened the way to genuine mysticism by his insistence that human speculation can never attain to the ineffable first principle. Unwilling even to call this principle by “the One”, Damascius declared that men cannot adequately describe its relation to derived reality. This first principle is beyond the reach of human thought and language and is utterly outside the hierarchy of reality. Because it is outside, everything, and particularly the soul of man, can participate in it directly and without intermediary, though in an unspeakably mysterious way. Though a pagan, Damascius thus pointed the way to later Christian mystics.[30]

Neoplatonism continued to flourish in Rome and Alexandria during the time of the late Academy in Athens, but no notable ideological changes occurred in it in either location. It continued in Rome until the latter part of the sixth century.

Among its products was the Neoplatonic Christian Mariu Victorinus (c. 350), whose Latin translations of Neoplatonic literature were read by Augustine and Boethius (c. 470-535). The Alexandrian School of Neoplatonism began in the middle of the fourth century and appears to have maintained strong connections with Athenian Neoplatonism at this time, including exchanging professors. Generally, the Alexandrian Neoplatonic professors remained closer to the thought of Plato and the Middle Platonists and did not enter into metaphysical speculations, theology, and theurgy, as did the Athenians, and they displayed a more conciliatory attitude toward Christianity. [31]

Neoplatonism and Theosophy

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky would have called Neoplatonists Theosophists. In The Keys to Theosophy she states: “The name Theosophy dates from the third century of our era and began with Ammonius Saccas and his disciples who started the Eclectic Theosophical system.” “They (Neoplatonists) were the Theosophists of early centuries."[32] In fact, Ammonius Saccas was the first to use the term "theosophy," which means "divine wisdom," combining "god" or "divine" (theos) and wisdom (sophia).

In Isis Unveiled she wrote that

“the Platonic philosophy is the most elaborate compend of the abstruse systems of old India, that can alone afford us this middle ground. Although twenty-two and a quarter centuries have elapsed since the death of Plato, the great minds of the world are still occupied with his writings. He was, in the fullest sense of the word, the world's interpreter. And the greatest philosopher of the pre-Christian era mirrored faithfully in his works the spiritualism of the Vedic philosophers who lived thousands of years before himself, and its metaphysical expression. Vyasa, Djeminy, Kapila, Vrihaspati, Sumati, and so many others, will be found to have transmitted their indelible imprint through the intervening centuries upon Plato and his school. Thus, is warranted the inference that to Plato and the ancient Hindu sages was alike revealed the same wisdom. So, surviving the shock of time, what can this wisdom be but divine and eternal?” [33]

There are a lot of overlaps between Neo-Platonism and Theosophy. Both teach a process of emanation from the divine source into differentiated forms, and a return journey to unity and emphasize the soul’s spiritual evolution and its eventual return to Source through inner awakening. Both traditions see gnosis or higher knowledge as the means to liberation, and reason as a lower step toward it; they emphasize a hierarchical cosmos in which beings serve as bridges to the divine as well as spiritual discipline and transformation, not only intellectual belief. Let’s look at some comparative quotes:

| Topic | Plotinus | Proclus | H.P. Blavatsky |

|---|---|---|---|

| The One/Absolute | “The One is beyond all multiplicity and diversity." | "Every good tends to unify what participates it; and all unification is a good; and the Good is identical with the One." | "It is 'Be-ness' rather than Being... an Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable PRINCIPLE." |

| Soul's Return / Union | "The soul is inherently divine and possesses the potential for union with the One." | "Everything is overflowing with Gods." | “The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul... and the obligatory pilgrimage for every Soul." |

| Knowledge/Intuition | You can only apprehend the Infinite by a faculty that is superior to reason." | "Wherever there is number, there is beauty." | "Everything in the Universe... is conscious: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception." |

| Spiritual Practice / Transformation | “The mystical experience is a flight of the alone to the alone." | "This, therefore, is mathematics: she reminds you of the invisible form of the soul... she awakens the mind and purifies the intellect." | "Everything in the Universe... is conscious: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception." |

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Western Renaissance and Modern Neo-Platonism

Western Renaissance

George Gemistos Pletho (1355-1452), a prominent Byzantine scholar, is a central figure in the revival and transmission of Neoplatonism in the West, particularly during the Renaissance. Concerned more with the advancement of Neoplatonic philosophy than with religious questions, Plethon delivered to the Florentine humanists at the Council of Ferrara–Florence his treatise “On the Difference Between Ristotle and Plato.” This work fired the humanists with a new interest in Plato (who had been ignored in the West during the Middle Ages because of the preoccupation with Aristotle) and inspired Cosimo de’Medici with the project of founding the Platonic Academy of Florence. [35]

The work of the humanist Platonist Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), who translated Plotinus' writings into Latin in 1484-1486 and then commented on them from the perspective of his Christian Neoplatonism, was groundbreaking. His work sparked the Florentine Platonic Renaissance, shaping European intellectual life for more than two centuries.[36]

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) was another Neoplatonist during the Italian Renaissance. He could speak and write Latin and Greek and had knowledge on Hebrew and Arabic. The pope banned his works because they were viewed as heretical – unlike Ficino, who managed to stay on the right side of the church. He was introduced to the Hebrew Kabbala and became the first Christian scholar to use Kabbalistic doctrine in support of Christian theology. [37]

The Cambridge Platonists

Some elements of Florentine Neoplatonism were imported into England in the 1490s by John Colet (1466-1519), who was then Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Colet carried on correspondence with Ficino, wrote a commentary on the writing of pseudo-Dyonysius, and paved the way for the 17th century Neoplatonists known as the Cambridge Platonists. [38]

The Cambridge Platonists represent the most important school of Platonic philosophers between the Italian Renaissance and the Romantic Age. They were a group of English seventeenth-century thinkers associated with the University of Cambridge. The most important philosophers among them were Henry More (1614–1687) and Ralph Cudworth (1617–1688), both fellows of Christ’s College, Cambridge. The group also included Benjamin Whichcote (1609–1683), Peter Sterry (1613–1672), John Smith (1618–1652), Nathaniel Culverwell (1619–1651), and John Worthington (1618–1671). All of them studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, apart from More who studied at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where Cudworth was later appointed Master.

They only came to be referred to as Platonists in the eighteenth century. But in so far as they all held the philosophy of Plato and Plotinus in high regard, and adopted principles of Platonist epistemology and metaphysics, the designation ‘Platonist’ is apt.[39]

Theosophists and the Neoplatonic Tradition

Alexander Wilder (1823-1909) was an American physician and Neoplatonist scholar, and a prominent early member of the Theosophical Society. He wrote the pamphlet New Platonism and Alchemy: A Sketch of the Doctrines and Principal Teachers of Eclectic or Alexandrian School. It was this brief work of some 30 pages that provided Madame Blavatksy with the necessary informatiuon on Ammonius Saccas and his disciples. [40]

Thomas Moore Johnson (1851-1919) was an attorney, collector, and student of philosophy in Osceola, Missouri. Though his formal training in philosophy was sparse, his consummate philosophical interests led him to become a foremost lay authority on Plato and the Neoplatonists. He translated Neoplatonist works such as Iamblichus’ Exhortation to the Study of Philosophy (1907), Proclus’ Metaphysical Elements (1909) and Opuscula Platonia (1908). He edited the periodical The Platonist, which was subtitled "An exponent of the philosophic truth, and devoted chiefly to the dissemination of the Platonic philosophy in all its phases." Published from 1881 until 1888, it was superceded by Bibliotheca Platonica.[41]

Books

Mills, Joy. The Keys to Theosophy: H. P. Blavatsky : an Abridgement. , 2013. Internet resource. P. 1.

Harris, R B. Neoplatonism and Contemporary Thought. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. Print.

Harris, R B. The Significance of Neoplatonism. Norfolk, Va: International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University, 1976. Print.

Online resources

Articles

- The Eclectic Philosophy by Alexander Wilder.

- Neoplatonism in Theosophy World.

- Plotinus in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Theurgy and Magic in Hermetic Kabbalah website.

- Hypatia of Alexandria (ca. 370-415 A.D.) in Tripod.com.

Audio

Video

- Turning-Points for the West: From Pythagoras and Plato through Gnosticism and Neoplatonism by Stephan Hoeller and Tony Lysy, presented on September 11, 2004 at the Theosophical Society in America.

- All About Platonism series by Mindy Mandell.

- Transformation. Added January 31, 2022. 28 minutes.

- Things in Themselves. Added December 6, 2021. 27 minutes.

- Dialectic. Added January 17, 2022. 17 minutes.

- Menexenus. Added April 12, 2021. 24 minutes.

- Purification. Added February 7, 2022. 29 minutes.

- Plotinus 1:6 Beauty. Added January 24, 2022. 27 minutes. Discusses Neoplatonism.

- 12 Gods of the Phaedrus. Added January 10, 2022. 13 minutes.

Notes

- ↑ National Gallery NG 200. Neoplatonism https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary/neoplatonism. Accessed on 5/5/25

- ↑ World History Edu. What is Neoplatonism.1/31.25. https://worldhistoryedu.com/what-is-neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/25.25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS.Ammonius SaccasTHEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 2, December, 1936, pages 53-59; number 9 of a 29-part series

- ↑ Dr. Siemons, Jean-Louis. Theosophical History, Occasional Papers, Vol. III. Ammonius Saccas and his “Eclectic Philosophy” as presented by Alexander Wilder.Theosophical History; Fullerton, Ca. 1994, p. 9

- ↑ Copleston, S.J. A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 463 https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, Franz. In the Pronaos of the Temple of Wisdom. Chapter 2. 1890. https://sacred-texts.com/sro/ptw/ptw04.htm Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ Copleston, S.J. A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 464 https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.

- ↑ Aubry, Gwenaelle. Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism. In: The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism. Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48

- ↑ Porphyry.Vita Plotini. p.3. Access through subscription.

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8

- ↑ Porphyry.Vita Plotini. 16-18. Access through subscription.

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.

- ↑ Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Aubry, Gwenaelle. Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism. In: The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism. Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48

- ↑ Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Proclus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/proclus/. Accessed on 4/30/25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11

- ↑ Proclus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/proclus/. Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Britannica. Hypatia.</> https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hypatia. Accessed on 5/5/25

- ↑ http://plato2051.tripod.com/hypatia_of_alexandria.htm

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. HYPATIA: THE LAST OF THE NEOPLATONISTS. THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, March, 1937. Pages 197-207; Number 12 of a 29-part series.

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11-12

- ↑ Britannica. Dasmcius. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Damascius Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11-12

- ↑ Mills, Joy. The Key to Theosophy: H. P. Blavatsky : an Abridgement. Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Ill. 2013. P. 1

- ↑ Blavatsky, Helena. Isis Unveiled Page 15. https://www.theosophy-ult.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/isis-unveiled-vol1.pdf Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ Reece, Gwendolyn. Neoplatonism: The Beginning of Theosophy in the West Four week course for the Online-School of Theosophy. Available at the end of 2025

- ↑ Britannica. George Gemistus Plethon https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Gemistus-Plethon. Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Marsilio Ficino, Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Marsilio-Ficino, Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Britannica. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola https://www.britannica.com/biography/Giovanni-Pico-della-Mirandola-conte-di-Concordia Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 18

- ↑ The Cambridge Platonists. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cambridge-platonists/ Accessed on 5/6/25

- ↑ Dr. Siemons, Jean-Louis. Theosophical History, Occasional Papers, Vol. III. Ammonius Saccas and his “Eclectic Philosophy” as presented by Alexander Wilder.Theosophical History; Fullerton, Ca. 1994, Foreword.

- ↑ University of Missouri. Thomas Moore Johnson Collection of Philosophy. https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/collections/show/6 Accessed on 5/6/25