Cagliostro

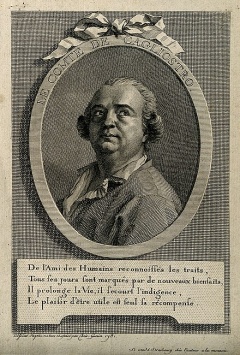

Count Alessandro di Cagliostro (June 2, 1743 – August 26, 1795) was an Italian adventurer and magician. He became a glamorous figure associated with the royal courts of Europe where he pursued various occult arts, including psychic healing, alchemy, and scrying. His reputation lingered for many decades after his death, but continued to deteriorate, as he came to be regarded as a charlatan and impostor. [1] Helena P. Blavatsky disagreed most strongly with such a verdict, claiming him to have been a wonderful and highly accomplished person. She laid much of the blame for the evil reputation he suffered on Carlyle, who called Cagliostro the "Quack of Quacks".[2]

According to various researchers, Cagliostro was the alias of the notorious Italian adventurer Giuseppe Balsamo. This claim is based upon the lies of Theveneau de Morande, a French spy and blackmailer who, in the words of a brilliant study by M. Paul Robiquet, was "from the day of his birth to the day of his death utterly without scruple"; and upon a Life of Balsamo published anonymously in 1791 under the auspices of the Inquisition. In 1890 H. P. Blavatsky boldly took issue with these two "authorities" by declaring that "whoever Cagliostro's parents may have been, their name was not Balsamo.”[3]

Early Years

It is a challenge to assemble a biographical sketch of Cagliostro due to a lot of legendary material that surrounds him. It is therefore necessary to apply a critical eye when dealing with the myriad contradictions. According to popular belief, Cagliostro’s real name was Giuseppe Balsamo, born in Sicily in 1743. [4] [5] In connection with Malta, the furthest some authors might go is to the acknowledge the importance of the town Malta for Cagliostro: “Regarding his birthplace, whether metaphorical or in terms of reality, one may at least say that Malta lay at the very heart of Cagliostro’s development.” [6] However, within recent years, doubts have arisen to whether this belief is in accord of the facts. It seems, that a tirade of abuse heaped upon Cagliostro were directed against the wrong man. [7]

In fact, W. R. H. Trowbridge, one of Cagliostro's biographers, made a convincing case that Cagliostro was not the same as Joseph Balsamo, with whom his detractors have identified him. Balsamo was a Sicilian vagabond adventurer, and the statement that he and Cagliostro were one and the same person originally rests on the word of the editor of the Courier de l'Europe, and upon an anonymous letter from Palermo to the chief of the Paris police. [8][9][10] Some chroniclers believe that Cagliostro must have been the natural son of Manoel Pinto de Fonseca and the Governor of Trebiazond’s daughter. Althotas, the Grand Master’s confidential adviser, supposedly took the newborn baby to Medina. From Malta, the Grand Master made arrangements to ensure the child’s future. [11] Cagliostro himself stated in his Memoirs that he had been born of Christians of noble birth but abandoned as an orphan upon the island of Malta. Cagliostro further shared in his memoirs that his earliest recollections took him back to the holy city of Medina in Arabia, where he was called Acharat and where he lived in the palace of the Muphti Salahaym. Four persons were attached to his service, the chief of whom was an Eastern Adept named Althotas who instructed him in the various sciences and made him proficient in several Oriental languages. Although both teacher and pupil outwardly conformed to the religion of Islam, Cagliostro later wrote, "the true religion was imprinted in our hearts." [12]

When Caglistro was twelve years old, he and Althotas began their travels. They first stayed for three years in Mecca, living in the palace of the Cherif. The day they departed the aged Cherif pressed the boy to his bosom and exclaimed: "Nature's unfortunate child, adieu!"

Caglisotro also wrote that the pyramids In Egypt were to the Adept-eye of Althotas holy fanes of initiation. After wandering through Asia and Africa for three years, the two reached the Island of Malta. There Althotas donned the insignia of the Order, and the young wanderer assumed European dress for the first time and received from his teacher the name of Cagliostro. Althotas died in Malta [13], and Cagliostro, accompanied by the Chevalier d'Acquino, then visited Sicily and the Isles of Greece, stopped for a while in Naples, and finally reached Rome, where he made the acquaintance of Cardinal Orsini and the Pope. It was in Rome, when Cagliostro was twenty-two years old, that he met and married Lorenza Feliciani, who proved to be a tool of the Jesuits and the chief cause of his troubles. [14]

London

In 1776 the Count and Countess Cagliostro were occupying apartments in Whitcombe Street, Leicester Fields, London. Cagliostro, now a man of twenty-eight, and spent most of his time in his chemical laboratory. His extreme good nature and the blind confidence which he placed in his friends made him their easy victim, and when he left London eighteen months later he sadly confessed that they had swindled him of 3,000 guineas. [15]

On April 12, 1777, Cagliostro became a Freemason (see below). He founded an Egyptian Rite in Masonry and made his first speech on Egyptian Masonry in The Hague, where a Lodge was formed in accordance with the Rite. In Nürnberg, when Cagliostro was asked for his secret sign, he replied by drawing the picture of a serpent biting its own tail. This symbol was the “Circle of Necessity” of the ancient Egyptians, and it is also found on the seal of the Theosophical Society. After establishing his Egyptian Rite in other German cities, Cagliostro arrived in Mittau, capital of the Duchy of Courland, in March 1779. Cagliostro was immediately invited to give an exhibition of his occult powers. He refused, declaring that such powers should never be displayed for the gratification of idle curiosity. Later, after much persuasion, he consented. As a result, some of his new friends began to look upon him as a supernatural being, while others denounced him as a charlatan. Cagliostro then proceeded to St. Petersburg, where he appeared for the first time as a magnetic healer. In May 1780, he arrived in Warsaw, then a great stronghold of both Masonry and Occultism. In September 1780, Cagliostro traveled to Strasbourg, where he gave up his entire time to altruistic service. He supported his poor patients for months at a time, often lodging them in his own house and feeding them at his own table. Like Mesmer, Cagliostro treated his patients magnetically, applying the force directly without the aid of magnetized objects. When he left Strasbourg 15,000 people claimed to have been helped by him. After leaving Strasbourg, Cagliostro went to Bordeaux and Lyons, where Saint-Martin had formerly lived. These cities welcomed him as a new prophet, and many influential men and women were initiated into his Egyptian Rite. In Lyons his Rite was so highly acclaimed that a special Temple was built for its observance, which later became the Mother Lodge of Egyptian Masonry. Cagliostro settled in Paris in 1785, and his house on the Rue St. Claude became the talk of the town. [16]

Freemasonry

On April 12, 1777, Cagliostro became a Freemason. His life in Egypt, his association with the Temple-priests, and his probable initiation into some of the Egyptian mysteries had fired him with a determination to found an Egyptian Rite in Masonry based upon these Mysteries, the aim of which was the moral and spiritual regeneration of mankind. [17]

Cagliostro did not think that there should be any separation between Freemasonry, Hermeticism and alchemy because for him they were the pathway to divinity, and to perfection of the soul. He firmly believed that all these principles be taught in balance to achieve balance; without one there could be no other – they co-existed as a total spiritual path.

Thus, if regular Freemasonry could not understand this, then he would create his own ritual encompassing all the qualities he understood to be imperative for the perfection of mankind through the immortality of the soul.

His healing practices, his alchemy and teachings in the Egyptian Rite were a blend of natural and supernatural sciences – a perfect synergy in action.

A recent translation of the ritual has shown that it is the foundation of a progressive path of spiritual and practical alchemy; a tradition that had been at work secretly throughout Europe for several hundred years and before that combined within both orthodox and unorthodox religions, forged from its roots in the Ancient Egyptian Hermetic teachings.

Cagliostro believed that Freemasonry, as a concept, had existed since time began and had continued through the teachings of all the major religions as the quest to become ‘perfected’ and to allow its members to become at one with the Supreme being. This was reflected in the historical references to the Pharaohs of Egypt and to the biblical figures of Moses, Elijah, Enoch, and Jesus – all, who by becoming spiritually and physically perfect, were rewarded with immortal life at the side of the Divine.

Cagliostro further believed that mankind could only be saved if they were restored to the state of innocence as before the ‘fall’. [18] Cagliostro's Egyptian Rite was open to both sexes; he declared that since women had been admitted into the ancient Mysteries there was no reason why they should be excluded from the modern order. His actions attracted the attention of the Masonic lodged in Paris and invited Cagliostro to attend a conference to clear up important questions concerning Masonic philosophy and he accepted the invitation. [19]

In the history of modern magical movement, Cagliostro’s Arcana Arcanorum, as understood by a subsequent magical tradition in which the Italian Magus is venerated as the founder, stands for three different things. Firstly, it indicates a theurgical system of evocation, by use of various techniques, of the Holy Guardian Angels, or other angels. Secondly, it means a practice of laboratory alchemy, in which dew drops, blood, gold and urine were variously combined. Thirdly, it means a practice of inner alchemy. [20]

The Necklace Affair

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace was an incident from 1784 to 1785 at the court of King Louis XVI of France of France that involved his wife, Queen Marie Antoinette. Cagliostro was accused of complicity in the affair and sent to the Bastille. After being imprisoned for nine months he was honorably acquitted, but at the same time he was asked to leave France. [21] Later the fact was established that he had actually warned Cardinal de Rohan of the intended crime. This and scandal and other accusations in England destroyed Cagliostro’s reputation and he was broken-hearted. [22]

Last Years

After Cagliostro’s reputations was destroyed, he wandered for some time and arrived in Rome in the spring of 1789. Making one last desperate effort to revive his Egyptian Rite, he was prevailed upon to initiate two men, who proved to be spies of the Inquisition. On the evening of December 27, 1789, he was arrested and thrown into a dungeon in the Castle of St. Angelo. Shortly afterward he was sentenced to death, the sole charge against him being that he was a Mason, and therefore engaged in unlawful studies. [23]

During his imprisonment Cagliostro’s private papers, family relics, diplomas from foreign Courts, his Masonic regalia and even his manuscript on Egyptian Masonry were publicly burned in the Piazza della Minerva. While the condemned Occultist was awaiting his fate, a mysterious stranger demanded an audience with the Pope. He was received, and immediately thereafter Cagliostro’s death sentence was changed to life imprisonment in the Castle of St. Leo, located on the frontiers of Tuscany. Here he languished for three years, writing a sentence every day on the walls of his living tomb. [24]

One of the cryptic messages, when interpreted, reads: “In 1789 the besieged Bastille will on July 14th be pulled won by you from top to bottom.” [25] The last entry bears the date of March 6, 1795. Exactly seven months later, on October 6, the Paris Moniteur contained a small paragraph announcing that “it is reported in Rome that the famous Cagliostro is dead.” If this statement was true, and Cagliostro actually did die in the Castle of St. Leo, why are tourists shown the little square hole in the Castle of St. Angelo in Rome where he is said to have expired? After his supposed death it was whispered that Cagliostro had escaped from his dungeon in some miraculous manner, thus forcing his jailers to spread the news of his death. Blavatsky says that “having made a series of mistakes, more or less fatal, he was recalled.” His downfall, she declared, was due to his weakness for an unworthy woman and to his possession of certain secrets of nature which he refused to divulge to the Church.[26] Sincere investigator of the facts surrounding the life and mysterious “death” of Cagliostro are of the opinion that the stories circulated against him may be traced to the machinations of the Inquisition, which in this manner sought to justify his persecution. The basic charge against Cagliostro was the he had attempted to found a Masonic lodge in Rome – nothing more. All other accusations are of subsequent date. [27]

Additional Comment

Count de St. Germain was thoroughly conversant with the principles of Oriental esotericism. He practiced the Eastern system of meditation and concentration, upon several occasion having been seated with his fee crossed and hands folded in the posture of a Hindu Buddha. He had a retreat in the heart of the Himalayas to which he retired periodically from the world. [28]

Massimo Introvigne, an Italian Roman Catholic sociologist of religion argued in one of his essay about Cagliostro

"We have followed together the shadow of Cagliostro and have seen the influence, at times indirect but more often direct, which he has exercised on a large number of diverse movement. Even if the relevance of these movements is downplayed, they nevertheless have some thousands of followers. Those who, including the present author, observe these magical movements from the point of view of the Roman Catholic scholar, cannot avoid being critical of their world view and practices. […] The most important part of the rituals of the Cagliostro lineage is something else. It consists of a form of auto-redemption in which the magical will of a person captures his or her own immortality, obtains eternal life, and thus becomes sovereign and lord over life and over death, having the power of God with respect to the same. It is this pretense of “becoming like God,” in a literal and not only a figurative sense, that seems to me to be the ultimate significance, and the principal challenge, of Cagliostro. In this sense, his legacy is still alive. "[29]

Additional resources

Articles

- Was Cagliostro a "Charlatan"? by H. P. Blavatsky

- Prince Talleyrand - Cagliostro by William Q. Judge

- Cagliostro at WisdomWorld.org

- Cagliostro, Alessandro in Theosophy World

Book

- Cagliostro by Trowbridge

Notes

- ↑ wikiwand. Cagliostro. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Alessandro_Cagliostro, accessed on 7/5/23

- ↑ Blavatsky, Helena. Collected Writings, Volume XII, pages 79-88

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Secret of all Ages Kindle edition.

- ↑ McCalman, Iain. The Last Alchemist: count Cagliostro, master of Magic in the Age of Reason. HarperCollinsPublisher, New York, N.Y. 2003, page 2

- ↑ Dumas, F. Ribadeau. Cagliostro George Allen and Unwin Ltd., Translated from French by Elisabeth Abbott, 1967, p. 15

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Secret of all Ages Kindle edition.

- ↑ Cagliostro (1743-1795). Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/cagliostro-1743-1795. Accessed on 7/25/23

- ↑ Hall, Manly The Comte Di Cagliostro. In The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Kindle edition.

- ↑ Trowbridge, W.R.H. Cagliostro: The Splendour and Mistery of a Master of Magic Chapmann and Hall, Ltd. London, 1910. Accessed online on 7/22/23 at https://www.theosophy.world/sites/default/files/ebooks/Trowbridge/Cagliostro%20-%20The%20Splendour%20and%20Misery%20of%20a%20Master%20of%20Magic%20-%20Trowbridge%2C%20W.pdf

- ↑ Dumas, F. Ribadeau. Cagliostro George Allen and Unwin Ltd., Translated from French by Elisabeth Abbott, 1967, p. 17

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23: https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Cagliostro (1743-1795). Encyclopedia.com. https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/cagliostro-1743-1795 Accessed on 7/25/23

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23: https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Faulks, Philippa. Canonbury Conference of Freemasonry, 2008. https://www.thesquaremagazine.com/mag/article/202004-count-alessandro-cagliostro/ Accessed on 7/26/23

- ↑ Hall, Manly p. The Comte Di Cagliostro. In The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Kindle edition

- ↑ Introvigne, Massiomo, Cagliostro, Alessandro di (ps. Of Guiseppe Balsamo). In: Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism by W.J. Hangegraaf, Antoine Faivre, Roelof van den Broek, and Jean-Poerre Brach. Brill, 2005

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Hall, Manly p. The Comte Di Cagliostro. In The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Kindle edition

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Hall, Manly p. The Comte Di Cagliostro. In The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Kindle edition

- ↑ Cagliostro. From “Great Theosophists”, in THEOSOPHY, Vol. 26, No. 12, October, 1938 (Pages 530-536, Number 27 of a 29-part series). Accessed online on 7/20/23 at https://blavatsky.net/Wisdomworld/setting/cagliostro.html

- ↑ Hall, Manly p. The Comte Di Cagliostro. In The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Kindle edition

- ↑ Hall, Manly. At various times he admitted that he was obeying orders of a power higher and greater than himself. The Secret Teachings of all Ages Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Introvigne, Massimo. Arcana Arcanorum: Cagliostro’s Legacy in Contemporary Magical Movements. Center for Studies on New Religions. Subscription with Academia.edu necessary for access.