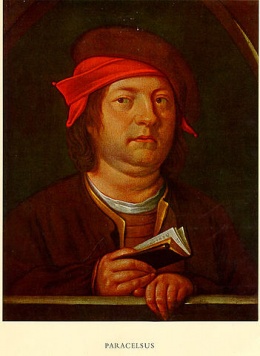

Paracelsus

Theophrastus Bombast of Hohenheim (1493-1541), called Paracelsus, was a Swiss physician, philosopher of nature, alchemist, lay theologian, and occultist. He was one of the most original and prolific authors of sixteenth-century Europe and his writings covered medicine, surgery, natural philosophy, alchemy, astronomy, natural magic, and reformation theology.

He introduced new ideas into medieval medicine, which was still bound to the theories of antiquity during his time and proposed a reform of Renaissance medicine and pharmacology.

As an interested layman he joined the general discussion on church reform. His respective views differed from the mainstream around Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli and can be assigned to the so-called radical reformation.

In the course of the 1520s, he challenged academic and urban authorities in Switzerland and South Germany by demanding medical reforms. Rebuffed by his opponents, he wandered from town to town for the remainder of his life, disseminating as an author, polemicist, and physician his understanding of medicine and nature. He died an obscure death in Salzburg, but before the end of the century his influence had spread, resulting in posthumous partisan controversies between advocates and detractors. [1][2]

Life, Education and Travels

Theophrastus Bombast of Hohenheim, later called Paracelsus, was most likely born on November 14, 1493 [3][4]or maybe on December 17, 1493[5][6]in Maria-Einsiedeln, not far from Zürich, Switzerland. His mother was a bondwoman (an unpaid servant or slave), and his father William an illegitimate offspring of the noble Bombasts of Hohenheim from Swabia. [7] 1502, when Paracelsus was 9 years old and after the death of his mother, his father moved to Villach, Carinthia, in order to become town physician. He died there in 1534 well respected. [8]Paracelsus received his early training from his father and from several clergymen. His father taught him among other things also alchemy and botany. He further learned the value of herbs, and their relations to the stars. Though sent to nearby Lavanttal to learn Latin, he was soon released by Bishop Erhard from grammatical studies so that they might pore over the problem of the Philosopher's Stone. Thus, Paracelsus escaped the orthodox education of the day and nurtured a desire to wander the world in search of more potent truths, for he did not believe that the secrets of nature could be told. In 1507 he became a travelling student. [9] Two other men influenced him deeply. He was a student of Johannes Trithemius, a German Benedictine abbot, polymath, and occultist, one of his teachers. The other person was Sigmund Füger, whose silver mine and laboratories Paracelsus visited for a year at the age of twenty-two. It is there that he acquired extensive knowledge of chemical and metallurgical processes.[10]There he also discovered that the most satisfactory way to learn was to observe and to experiment practically with the information when possible. [11]

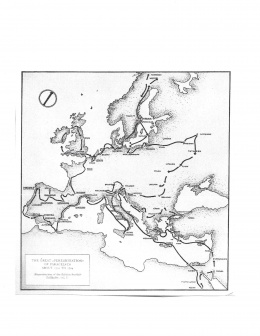

After studying at German, French, and Italian universities he was awarded a doctorate in medicine and surgery at the university of Ferrara, Italy, probably around 1515 or 1517. [12][13] After several years of traveling in Spain, England, Lithuania, and serving as an army physician, he tried to settle in Salzburg as a doctor (probably around 1524). The first dated writings of Paracelsus are from the Salzburg period, namely theological writings on the Virgin Mary, the Holy Trinity and a reformatory criticism of the practices of the traditional church. In the turmoil’s accompanying the Peasants' Wars, which had reached the city, Paracelsus took sides with the rebels and had to flee abruptly after their abatement in 1525, leaving behind most of his belongings. [14][15]

In 1526, Paracelsus arrived at Strasbourg where he gained citizenship and joined the surgeons' guild. In nearby Basel he successfully treated he famous printer Johannes Froben and was consequently appointed town physician and lecturer to the city and university of Basel in 1527, reaching so the climax of his career. Filled with the glowing vision of a new medicine based on experience in contrast to book knowledge, Paracelsus presented a series of lectures wherein he broke with practically every traditional concept. Because of his undiplomatic, quarrelsome and unyielding nature, Paracelsus soon clashed with the authorities. He had to leave Basel abruptly after only a few months, after a short period that had begun as a highly promising reform of medieval medicine. [16][17]

After Basel, Paracelsus was again subjected to endless wanderings, which in fact were to continue to the end of his life. He roamed Southern Germany, stayed in Nuremberg in 1529 and in Beratzhausen in 1530. During this time, he wrote tracts on syphilis and one of his most well-known works, the Paragranum, but in 1530 the printing of his books was forbidden by the officials of Nuremberg, a means by which he had hoped to reach a broader audience.

Paracelsus turned his way again to Switzerland and in 1531 remained for several months in the city of St. Gall. There he wrote another important medical work, his Opus paramirum, which he devoted to the well-known humanist and physician Joachim von Watt, called Vadian, but Vadian completely ignored him. In the face of these repeated disappointments, Paracelsus even at times considered giving up medical practice. He retired to the nearby Appenzell hills and confined himself to theological writing and preaching.

In 1534, Paracelsus went to the country of Tyrol, stopping at Innsbruck and Sterzing, where he encountered the outbreak of plague, and finally Meran. In 1535 he gave a consultation to the abbot of Pfäfers, a little spa town in the Swiss Rhine Valley. The written records of this meeting belong to the few remaining documents in Paracelsus's own handwriting. His greatest literary success was the publication of his Chirurgia magna (Great Surgery) in Augsburg in 1536, one of the very few printed books during his lifetime. In 1537 Paracelsus stayed at Eferding near Linz, Austria, where he completed the Astronomia magna, his main philosophical work.

In 1538 he was back in Carinthia, the former abode of his father. In a last creative effort, he tried to summarize and render more precisely his key ideas. [18]

Death

Paracelsus died in Salzburg on September 24th, 1541 after a short illness (at the age of forty-eight years and three days). The exact cause for his death is unknown. Some say that the cause was a chronic mercury intoxication as a late effect of his alchemical experiments. Others said that Paracelsus during a banquet had been treacherously attacked by the hirelings of certain physicians who were his enemies, and that in consequence of a fall upon a rock, a fracture was produced on his skull, that after a few days caused his death; while others claim he took an overdose of his vital elixir, was killed in a drunken brawl, or that enemies put poison into his wine. ”[19][20][21][22]And some say that Paracelsus drank pure alcohol in mistake for the Elixir of Life, and died.[23]

Paracelsus was buried, according to his request, in the graveyard of St. Sebastian’s Church, close to the city bridge in Salzburg. In 1572 his bones were dug up when a new chapel was added to the church and reburied by the graveyard wall. In 1752 Archbishop Andreas von Dietrichstein ordered that Paracelsus’s remains be moved again, this time to the marble tomb in the entrance porch of the church. [24]

The Name

Paracelsus, in the opinion of some biographers, is the translation of his last name “von Hohenheim”, but half Greek and half Latin. [25] Many other biographers believe that Hohenheim assumed the now famous surname after having attained the full doctor's dignity. Such procedure was fashionable among the humanist scholars of those days. Hohenheim picked Paracelsus, of one advancing farther and beyond the ancient Celsus's learning. Cornelius Celsus was a Roman patrician, lived some time in the first century of our era and had studied medicine.[26]

When Paracelsus was baptized, he probably got the name Philipp Theophrast; the second part seems to imply that his father had great hopes for his son. Paracelsus used the second part of his name and sometimes he called himself Aureolus Theophrastus. He probably came up with the name Paracelsus as a student; one rumor is to imply his scientific prowess. Sometimes he signed his name as (Helvetius) Eremita to hint at his birthplace. The publishers of his writings call him Phillipus Aureolus Theophrastus Paracelsus Bombastus ab Hohenheim.

[27]

Contributions to Medicine

Paracelsus dealt not merely with the external body of man, but more with the inner man and with the world of causes, never leaving out of sight the universal presence of the divine cause of all things. His medicine was therefore a holy science, and its practice a sacred mission, which, according to the Theosophist Franz Hartmann cannot be understood by those who are godless. Paracelsus, just like Hartmann, was convinced, that a physician who has no faith, and consequently no spiritual power in him, can be nothing else but an ignoramus and quack, even if he had graduated in all the medical colleges in the world and knew the contents of all the medical books that were ever written by man.[28]

In Paracelsus’ eyes a physician should be well experienced because there are many kinds of disease, know the laws of Nature, know the constitution of man, the invisible no less than the visible one.

The medicine of Paracelsus therefore rested upon four pillars, which are:

- Philosophy, i.e., the true perception and understanding of cause and effect and a knowledge of physical nature;

- Astronomy, i.e., the astral influences and a knowledge of the powers of the mind;

- Alchemy, i.e., a knowledge of the divine powers in man; and

- The personal virtue [holiness] of the physician.[29]

In his Book Paramirum about the “Five Entia”, one of the most important scriptures of Paracelsus, he divided the cause of all diseased into five classes:

- Ens Astrale: About the power and the nature of the stars and their influence on the body because the world is a Macrocosm and man is the Microcosm.

- Ens Venenale: About the effect of toxins (food and the role of the excretory organs).

- Ens Naturale: About the body making one sick through confusion and harming itself -constitution, diathesis, disposition.

- Ens Spirituale: About the spirits that make our body sick (Psychosomatics and Psychology).

- Ens Dei: About the work of God (Destiny and Karma)[30][31]

As there are five causes of diseases, so there are five different ways of removing them, and therefore five classes of physicians:

- Naturales: Treatment with opposite remedies; for instance, cold by warmth, dryness by moisture.

- Specifici: Employing specific remedies, of which it is known that they have certain affinities for certain morbid conditions. [Homœopathy] .

- Characterales: The physicians of this class have the power to cure diseases by employing their willpower [Magnetism, Suggestion, Mind-Cure].

- Spirituales: The followers of this system have the power to employ spiritual forces [e.g. Hypnotism]

- Fideles: Those who cure by the power of Faith, such as Christ and the apostles [Magic].

According to Paracelsus, among these five classes, the first one is usually the most orthodox and narrow-minded, and rejects the other four for not being able to understand them.[32]

Paracelsus used to heal wounds by cleaning bloody bandages with a strong disinfectant liquid which means he already understood the significance of antisepsis. The remedy he used was so strong though, that he could not apply it directly to the wound. According to his theory, the catharsis of the bloody bandages transferred itself to the wound: because it was connected to it and this connection remained even after physical separation. He applied the same principle to the function of the “weapon salve”, an attempt to heal a wound caused by a bladed weapon with an herbal preparation applied not to the wound itself but to the blade of the weapon that caused it. Sometimes Paracelsus even created wax copies of the diseased limbs and treated them. He operated on them and cleaned them with fire and vitriol. The secret was, that he first transferred the symptoms of the patients to the wax-copy using a procedure that Mesmer later called magnetization. [33][34]Albeit, this approach was ridiculed by his critics.[35]

In 1530 Paracelsus wrote a clinical description of syphilis, in which he maintained that the disease could be successfully treated by carefully measured doses of mercury compounds taken internally. He stated that the “miners’ disease” (silicosis) resulted from inhaling metal vapors and was not a punishment for sin administered by mountain spirits. He was the first to declare that, if given in small doses, “what makes a man ill also cures him” – an anticipation of the modern practice of homeopathy. Paracelsus is said to have cured many persons in the plague-stricken town of Stertzing in the summer of 1534 by administering orally a pill made of bread containing a minute amount of the patient’s excreta he had removed on a needle point.

He was the first to connect goiter with minerals, especially lead, in drinking water. He prepared and used new chemical remedies, including those containing mercury, sulfur, iron, and copper sulfate, thus uniting medicine with chemistry, as the first London Pharmacopoeia, in 1618, indicates. Paracelsus, in fact, contributed substantially to the rise of modern medicine, including psychiatric treatment. Swiss psychologist Carl Jung wrote of him that “we see in Paracelsus not only a pioneer in the domains of chemical medicine, but also in those of an empirical psychological healing science.” [36]

Paracelsus changed the course of Western medicine by insisting that the medical theories of antiquity, based on the notion of the four humors, should be replaced by an alchemical vision of how the body works. For him, the entire universe was an alchemical process wrought by God, in which ‘occult’ forces governed the relationships between the stars, the earth and the body. [37]

Alchemy

In general terms, Paracelsus understood by alchemy any process that transforms raw material into a finished product. God has made all things and these have a natural end to which they will come by the power of nature within them; but God has also assigned to man the power of transforming things from this natural or raw state to a condition fit for man's use. [38]

But alchemy is an art which cannot be understood without spiritual or soul knowledge. The highest aspect of alchemy is the re-generation of man in the spirit of God out of the material elements of his physical body. The physical body itself is the greatest of mysteries, because in it are contained in a condensed, solidified, and corporeal state the very essences which go to make up the substance of the spiritual man, and this is the secret of the “Philosopher’s Stone.”

The next aspect of alchemy is the knowledge of the nature of the invisible elements, constituting the astral bodies of things. Each thing is a trinity having a body and a spirit held together by the soul, which is the cause and the law. Physical bodies are acted upon by physical matter; the elements of the soul are acted upon by the soul, and the conscious spirit of the enlightened guides and controls the action of matter and soul.

The lowest aspect of alchemy is the preparation, purification, and combination of physical substances, and from this science has grown the science of modern chemistry. [39]

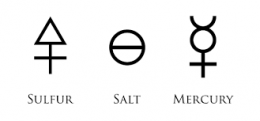

Paracelsus believed in the Greek concept of the four elements, but he also introduced the idea that, on another level, the cosmos is fashioned from three spiritual substances: The tria prima of Mercury, Sulfur, and Salt. These substances were principles that gave every object both its inner essence and outward form.

- Mercury represented the transformative agent (fusibility and volatility);

- Sulfur represented the binding agent between substance and transformation (flammability);

- Salt represented the solidifying/substantiating agent (fixity and non-combustibility).

The tria prima also defined the human identity. Sulfur embodied the soul (the emotions and desires); salt represented the body; mercury epitomized the spirit (imagination, moral judgment, and the higher mental faculties).

By understanding the chemical nature of the tria prima, a physician could discover the means of curing disease. [40]

Most of Paracelsus’ alchemical writings are hard to interpret today. He did not use his symbols consistently. Far from having any intention of making himself clear, he sought protection against spying and plagiary by deliberately omitting key factors from his formulas and prescriptions. A times he admitted that he was withholding the full truth or hinted at a secret cypher. Typical is the following passage:

”Do not take anything from the lion but the Rose-Colored Blood, and from the Eagle only the White Gluten. Coagulate as the ancients have directed, and you will obtain the Tinctura Physicorum. If this is incomprehensible to you, however, remember that only he who seeks with all his heart will find it.”[41][42]

Astrology

Astrology is intimately connected with medicine, magic, and alchemy. If one desires to make use of the influences of the planets for any purpose, it is necessary to know what qualities these influences possess — how they act, and at what time certain planetary influences will be on the increase or on the wane. The quality of the planetary influences will be known to a man who knows his own constitution, because he will then be able to recognize in himself the planetary influences corresponding to those that rule in the sky. Each body attracts those influences that are in harmony with it, and repels the others; the time when certain planetary influences rule may be found out by astronomical calculations, or by tables that have been prepared from such for that purpose; but the spiritually developed seer will require no books and no tables, but will recognize the conditions of the interior world by the states existing in his own mind. [43]

Opinions on astrology in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were diverse, and consistency was rare. Still, in an age without science, astrology seemed like a science and predictive astrology existed despite the fact that the Church was suspicious of it. Paracelsus had his own theories: “The stars have their own nature and properties” and astrology played a key role in Paracelsus' thoughts and medicine. [44]Astronomy and astrology meant for Paracelsus generally the parallelism between the large and the small world. He was not — what is called today — a professional astrologer. He did not calculate nativities or make horoscopes, but he knew the higher aspect of astrology, by which the mutual relations of the Macrocosm and the Microcosm are known. He rejected the errors of popular astrology as he did those of other popular religions or scientific superstitions; and his system of astrology, if rightly understood, appears of a sublime character and full of the grandest conceptions. [45]

The prophecies contained in Paracelsus's works on astrology and divination began to be separately edited as Prognosticon Theophrasti Paracelsi in the early 17th century. His prediction of a "great calamity just beginning" indicating the End Times was later associated with the Thirty Years' War.[46]Among the first writings the reader can find in the Huser edition (see under "Legacy") is a curios prophecy about France, a French emperor, and possibly the fall of the House of Bourbons. [47]

Negative Opinions and Rumors

Paracelsus had a lot of adversaries and enemies due to his exaggerated sense of mission and his difficult personality. [48] The following excerpt is but one example: “I want to elucidate and argue in such a way that until the last day of the world my writings must remain and will remain true, and yours are recognised as full of bile, poison, and brood of vipers and are hated by the people like toads. It is not my will that you should fall down or be knocked down a year hence, but you must show your shame after a long time and you certainly fall through the cracks, I shall judge you more after my death than before, and even if you eat my body, you have only eaten filth: the Theophrastus will struggle for the body with you.” [49]

Some of his opponents doubted that he really every received a diploma for medical studies. [50][51] [52] There are authors who even think that some of his travels are inventions of Paracelsus because he liked to boast. [53]

His colleagues took issue with the fact that he gave his lectures in German and alleged that he didn’t know Latin very well and was therefore forced to lecture in German.[54] [55]He also said in later years that he hadn’t read anything in ten years and that he dictated his writings ex abrupto and without any literary aids. [56]

Some critics say that it is challenging to judge the literary abilities of Paracelsus. They are destitute of any scientific method used in scholarly writings and he lacks the experience of scholars by tying his arguments to known traditions and cite other scholars. [57][58]

It has been written that Paracelsus was castrated in his youth. But there are different stories about how it has happened. One claim is, that his father had done the operation, others say he was attacked by a pig when he was 3 years old, others again said he was mutilated by a soldier as a child. It has also been said that it might have been a rumor because Paracelsus had never shown any interest in the other sex and had no beard, had a female-shaped head and aged at a young age. [59]

Legacy

Blavatsky wrote, that Paracelsus was the most wondrous intellect of his age and original thinker. She considered him as one of those great minds who had created a new mode of thinking on the natural existence of things. She quoted the astronomer Pfaff (1774-1835), who had publicized a book on astrology in 1816 [60] saying:

“What man has ever taken more comprehensive views of nature than Paracelsus? He was the bold creator of chemical medicines; the founder of courageous parties; victorious in controversy, belonging to those spirits who have created amongst us a new mode of thinking on the natural existence of things. What he scattered through his writings on the Philosopher’s stone, on Pigmies and Spirits of the Mines; on signs, on homunculi, and the Elixir of Life, and which are employed by many to lower his estimation, cannot extinguish our grateful remembrance of his general works, nor our admiration of his free, bold exertions, and his intellectual life.” [61]She also pointed out that Paracelsus was the first to discover and describe hydrogen and knew well all its properties and composition long before any of the orthodox academicians even thought of it; that he had studied astrology and astronomy, as all the fire-philosophers did; and that, if he did assert that man is in a direct affinity with the stars, he knew well what he asserted. [62]

The Theosophist Franz Hartmann wrote that Paracelsus was among those “who obtained their knowledge not merely from following the prescribed methods of learning, or by accepting the opinions of the ‘recognized authorities’ of their times, but they studied Nature by her own light, and becoming illuminated by the light of Divine Nature, they became lights themselves, whose rays illuminate the world of mind. What they taught has been to a certain extent verified and amplified by the teachings of Eastern Adepts, but many things about which the latter have to this day kept a well-guarded silence were revealed by Paracelsus three hundred years ago. Paracelsus threw pearls before the swine, and was scoffed at by the ignorant, his reputation was torn by the dogs of envy and hate, and he was treacherously killed by his enemies. But although his physical body returned to the elements out of which it was formed, his genius still lives; and as the eyes of the world become better opened to an understanding of spiritual truths, he appears like a star on the mental horizon, whose light is destined to illuminate the world of occult science, and to penetrate deep into the hearts of the coming generation, to warm the soil out of which the science of the coming century will grow.”[63]

Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthropology, and a former Theosophist, said in one of his lectures that spiritual research shows “the treasure, the spirit of knowledge, the investigation, and enlightenment of nature, which is hidden with Paracelsus”. He explained that Paracelsus had to be understood in another way than it normally happens if one becomes engrossed in a spirit of the past. One has to develop a living feeling of the object and the direction of thinking to which Paracelsus dedicated himself. He pointed out that, in order to understand Paracelsus, one must look at the basic character of his work as a doctor and as a philosopher and grasp him as a theosophist. He tried to grasp the construction of the world edifice. He was interested in the secrets of the starry heaven, became engrossed in the construction of the earth and the construction of the human being himself. This brilliant sight penetrated also into the secrets of the spiritual life. Nothing was mere theory in him, everything was immediate in such a way that it was bent on practise, that he wanted to use all that he knew for the welfare, the spiritual and physical health of the human being. This gives his work, his thinking, and investigations the big, immense unity. Steiner saw Paracelsus as an original, elementary personality and understood that he used an intuitive approach when treating patients. [64]

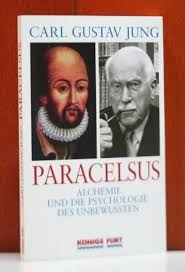

Paracelsus, contributed substantially to the rise of modern medicine, including psychiatric treatment. Swiss psychologist Carl Jung wrote of him that “we see in Paracelsus not only a pioneer in the domains of chemical medicine, but also in those of an empirical psychological healing science.”[65] Carl Jung was struck by the recurrence of alchemical symbols in his patients’ dreams and theorized that the symbolic language of alchemy was an expression of innate but unconscious psychological processes. He related alchemy to the psyche in the same way that Paracelsus had to physiology and it became key to his groundbreaking hypothesis of the collective unconscious and the process of “individuation”. [66]

In 1939 one could read in Knaur’s lexicon from Berlin: “Paracelsus: An outstanding physician, many-sided enquirer into natural sciences, and mystical philosopher; founder of the modern art of pharmacology and therapeutics… His ideas have recently acquired great influence in medical Science once more.” [67]

Colonel Fielding Hudson Garrison, MD, an acclaimed medical historian, said of Paracelsus, that he was the “precursor of chemical pharmacology and therapeutics, and the most original medical thinker of the 16th century” and that he was far ahead of his time in noting the geographic difference of disease, and that he was an outstanding reformer of medical practice standing between the old procedures and the rise of the modern scientific method.[68]

The author and one of his biographers, Dr. J. Strebel said: “Paracelsus belongs to those great masters of methodic knowledge and experimental investigation, who laid the foundations of our modern natural sciences.” [69]

The findings of Paracelsus included his discovery of hydrogen and nitrogen. He successfully developed methods for the administration of mercury in the treatment of certain diseases. He established a connection between cretinism and endemic goiter and introduced the use of mineral baths. The German philosopher Lessing was outspoken in his praise of Paracelsus and said that those who imagine that the medicine of Paracelsus is a system of superstitions, will, if they once learn to know its principles, be surprised to find that it is based on a superior kind of knowledge which we have not yet attained, but into which we may hope to grow. [70][71]

Paracelsus believed that knowledge was attained two ways – by experience and intuition and he believed that intuition was possible because of the existence in nature of a mysterious essence – a universal life force. [72]

He also believed that there are three suns in the solar system, the physical sun warming bodies and things, an astral belonging to the psychic sphere nourishing and revealing the structure of the soul and a spiritual one, sustaining and nourishing the human spirit. [73]

Paracelsus actually compared the human power of imagination with the sun. Even though its light is not tangible, it can warm as well as cause a fire. Man has to make a sun out of his own power of imagination, has to focus his will on that which he wants to affect. [74]

In the Paracelsus philosophy of the universe, all mutations of energy are due to relationships and not due to the actual alteration of any energy in itself. He also denied the existence of antipathetical energies and thus did not believe in the existence of factual evil. [75]

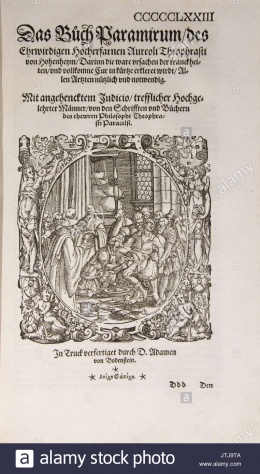

Paracelsus also had a substantial impact as a prophet or diviner, his Prognostications being studied by Rosicrucians (see Rosicrucianism) in the 1700s. He was venerated by German Rosicrucians, who regarded him as a prophet, and developed a field of systematic study of his writings, which is sometimes called "Paracelsianism", or more rarely "Paracelsism". [76]After Luther Paracelsus left behind the most extensive early modern professional literature in German. "Paracelsism" also produced the first complete edition of Paracelsus's works. Johannes Huser of Basel (c. 1545–1604) gathered autographs and manuscript copies, and prepared an edition in ten volumes during 1589–1591 and a collection of his surgical writings in Strasburg in 1605. [77]For the purpose of his collection Huser travelled extensively in Germany and Austria in search of early editions and manuscripts in Paracelsus’ own hand. [78]

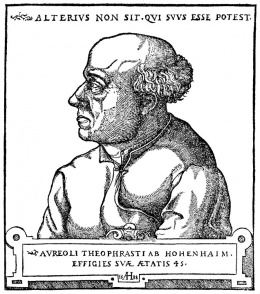

His motto was Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest ("Let no man belong to another who can belong to himself") and is inscribed on the 1538 portrait by Augustin Hirschvogel shown above.

Online resources

Articles

- Paracelsus at Theosophy World

- The Life of Paracelsus - PDF by Franz Hartmann

- Footnotes to "The Life of Paracelsus" by H. P. Blavatsky

- Paracelsus and the Substance of His Teaching by Franz Hartmann

- Paracelsus published by Theosophy Trust

- Paracelsus - Biography at the European Graduate School website

- Paracelsus at KatinkaHesselink.net

- Zurich Paracelsus Project from the University of Zurich

- Essential Philosophical Writings- Aries Book Series

- Biography of Paracelsus - in German by Zeno.org

- Paracelsus - in German by the Historical Lexicon Switzerland

- Paracelsus: Eine Skizze seines Lebens - in German by Em. Radl

- Paracelsus - A Lecture by Rudolf Steiner

- Noble Genius of Paracelsus by H.P.Blavatsky

- Paracelsus and Roman Censorship by Lyke de Vries

Notes

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Brill. Paracelsus. (Theophrastus Bombast of Hohenheim, 1493-1541). https://selfdefinition.org/magic/Paracelsus-Essential-Theoretical-Writings.pdf. Accessed on 7/9/10

- ↑ De Telepnef, Basilio. Paracelsus. A Genius amidst a troubled World. Zollikoffer & Co. St. Gallen, Switzerland. 1945. Page 13

- ↑ Hargrave, John. The Life and Soul of Paracelsus. Victor Gollancz Ltd., London. 1951. Page 20

- ↑ Hall, Manly. Alchemy. Kindle edition.

- ↑ Holmyard, E.G.Alchemy. Chapter 8,Paracelsus. https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/11604698 Accessed on 8/8/19 through ehoopla

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 63. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Theosophy Trust Memorial Library. Paracelsus. http://www.theosophytrust.org/316-paracelsus. Accessed on 7/11/19

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 66. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n7. Page 7. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Biographie von Paracelsus. Zeno.org. http://www.zeno.org/Philosophie/M/Paracelsus/Biographie. Accessed on 7/11/19

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Pages 123 – 136.

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Pages. 187 - 214

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 14. Accessed on 7/12/19

- ↑ The Scope of Paracelsus Study. Zurich Paracelsus Project. https://www.paracelsus.uzh.ch/index.html. Accessed 6/4/19

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Page 338.

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n7. Page 7. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Hargrave, John. The Life and Soul of Paracelsus. Victor Gollancz Ltd., London. 1951. Page 253

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Page 339-340

- ↑ Wegand, 1789. Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Schwarzkünstler, Goldmacher, Teufelsbanner, Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwärmer, Wahrsager, und anderer philosophischer Unholden [The History of Human Folly, or Biographies of Famous Black Magicians, Makers of Gold, Banishers oft he Devil, Soothsayers, Dreamers, Fortunetellers, and other Philisophical Fiends.] https://books.google.de/books?id=87pTAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed on 7/15/19)

- ↑ De Telepnef, Basilio. Paracelsus. A Genius amidst a troubled World. Zollikoffer & Co. St. Gallen, Switzerland. 1945. Page 28

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 63. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 115. Accessed on 7/30/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Pages 117-123. Accessed on 7/30/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Pages 133-151. Accessed on 7/30/19

- ↑ Paracelsus. Health and Healing. https://www.paracelsus-magazin.ch/en/paracelsus-medicine/the-five-entia-of-paracelsus-i/. Accessed on 7/30/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page151. Accessed on 7/30/19

- ↑ Hauf, Monika (2016). Kompendium der Magie und des Okkultismus. Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig, Germany; page 141

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Pages 79-80

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Page 375, pages 378-379

- ↑ Hargrave, John. Paracelsus. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Paracelsus. Accessed on 7/29/19

- ↑ Ball, Philip and Shamdasami, Sonu. Alchemny of the Psyche. http://londonmonthofthedead.com/transformation.html. Accessed on 7/29/19

- ↑ Holmyard, E.G.Alchemy. Chapter 8, Paracelsus. https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/11604698 Accessed on 8/12/19 through ehoopla.

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 156. Accessed on 7/12/19.

- ↑ Paracelsus. History of Alchemy. http://historyofalchemy.com/list-of-alchemists/paracelsus/. Accessed on 7/30/10.

- ↑ Pachter, Henry. Paracelsus. Magic into Science. 1951 Henry Schuman, New York. Page 116.

- ↑ Huser, Vol. VI, p. 373.

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 169. Accessed on 7/12/19.

- ↑ Ball, Phillip. The Devils Doctor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. 2006. Pages 278 - 288.

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 169. Accessed on 7/12/19.

- ↑ Weber, Eugen. Apocalypses: Prophecies, Cults, and Millennial Beliefs Through the Ages (2000). https://books.google.com/books?id=nz5m0vZHYx8C&pg=PA86#v=onepage&q&f=false. Page 86. Accessed on 7/29/19.

- ↑ Kiesewetter, Karl. Die Geheimwissenschaften [Secret Sciences]. Verlag von Wilhelm Friedrich. Leipzig. 1894. Pages 328 – 331 – [Rare Book Collection, Olcott Library].

- ↑ Paracelsus. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/012196/2010-09-27/. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Steiner, R. The Riddles of the World and Anthroposophy. Paracelsus. April 26th, 1906. https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA054/English/eLib2014/19060426p01.html. Accessed on 7/12/19

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 67. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Wegand, 1789. Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Schwarzkünstler, Goldmacher, Teufelsbanner, Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwärmer, Wahrsager, und anderer philosophischer Unholden [The History of Human Folly, or Biographies of Famous Black Magicians, Makers of Gold, Banishers oft he Devil, Soothsayers, Dreamers, Fortunetellers, and other Philisophical Fiends.] https://books.google.de/books?id=87pTAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false. Page 217 ff. Accessed on 7/15/19).

- ↑ Hauf, Monika (2016). Kompendium der Magie und des Okkultismus. Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig, Germany; page 140

- ↑ Wegand, 1789. Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Schwarzkünstler, Goldmacher, Teufelsbanner, Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwärmer, Wahrsager, und anderer philosophischer Unholden [The History of Human Folly, or Biographies of Famous Black Magicians, Makers of Gold, Banishers oft he Devil, Soothsayers, Dreamers, Fortunetellers, and other Philisophical Fiends.] https://books.google.de/books?id=87pTAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false. Page 222. Accessed on 7/15/19)

- ↑ Wegand, 1789. Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Schwarzkünstler, Goldmacher, Teufelsbanner, Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwärmer, Wahrsager, und anderer philosophischer Unholden [The History of Human Folly, or Biographies of Famous Black Magicians, Makers of Gold, Banishers oft he Devil, Soothsayers, Dreamers, Fortunetellers, and other Philisophical Fiends.] https://books.google.de/books?id=87pTAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false. Pages 217 and 226. Accessed on 7/15/19)

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 85. Accessed 7/16/19

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 69. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 68. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Hauf, Monika (2016). Kompendium der Magie und des Okkultismus. Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig, Germany; page 140

- ↑ Wegand, 1789. Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder Lebensbeschreibungen berühmter Schwarzkünstler, Goldmacher, Teufelsbanner, Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwärmer, Wahrsager, und anderer philosophischer Unholden [The History of Human Folly, or Biographies of Famous Black Magicians, Makers of Gold, Banishers oft he Devil, Soothsayers, Dreamers, Fortunetellers, and other Philisophical Fiends.] https://books.google.de/books?id=87pTAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false. Page 216. Accessed on 7/15/19) /><Radl, Em. Paracelsus. Eine Skizze seines Lebens. Isis Vol. 1, No. 1 (1913), pp. 62-94 (33 pages), Published by: The University of Chicago Press On behalf of the History of Science Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/223807?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A68d03a89a6c85f5116e9ed9c1d5a5acd&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. Page 64. Accessed 7/9/19

- ↑ Oestmann G., Rutkin, D., Kocku von Tuckrad. (eds.). J. W. A. Pfaff and the Rediscovery of Astrology in the Age of Romanticism. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263820092_J_W_A_Pfaff_and_the_Rediscovery_of_Astrology_in_the_Age_of_Romanticism. Accessed on 9/12/19)

- ↑ Blavatsky, H.P. The Noble Genius of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/the-noble-genius-of-paracelsus.pdf. Page 6. Accessed 7/11/19

- ↑ Blavatsky, H.P. The Noble Genius of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/the-noble-genius-of-paracelsus.pdf. Page 15. Accessed 7/11/19

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, F. The Life and the Substance of the Teachings of Paracelsus. http://www.philaletheians.co.uk/study-notes/buddhas-and-initiates/paracelsus-by-franz-hartmann.pdf. Page 9. Accessed on 7/12/19

- ↑ Steiner, R. The Riddles of the World and Anthroposophy. Paracelsus. April 26th, 1906. https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA054/English/eLib2014/19060426p01.html. Accessed on 7/12/19

- ↑ Hargrave, John. Paracelsus. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Paracelsus. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Alchemy of the Psyche. http://londonmonthofthedead.com/transformation.html. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ De Telepnef, Basilio. Paracelsus. A Genius amidst a troubled World. Zollikoffer & Co. St. Gallen, Switzerland. 1945. Page 79

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus. https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n5. Page 5. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ De Telepnef, Basilio. Paracelsus. A Genius amidst a troubled World. Zollikoffer & Co. St. Gallen, Switzerland. 1945. Page 79

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n7. Page 7. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Paracelsus, Physician and Philosopher. WRF. Your Global Source for Health Information. http://www.wrf.org/men-women-medicine/paracelsus-physician-philosopher.php Accessed 7/29/19

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus. https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n9. Page 9 Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus. https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n11. Page 12. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Hauf, Monika (2016). Kompendium der Magie und des Okkultismus. Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig, Germany; page 141

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical and Medical Philosophy of Paracelsus. https://archive.org/details/180838745ManlyPHallPARACELSUS/page/n13. Page 13. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Lyke de Vries. Paracelsus and Roman Censorship - Johannes Faber 1616 Report in Context. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17496977.2017.1361060. Accessed 7/29/19

- ↑ Paracelsus. Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz. https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/012196/2010-09-27/. Accessed on 7/15/19

- ↑ Holmyard, E.G.Alchemy. Chapter 8, Paracelsus. https://www.hoopladigital.com/title/11604698 Accessed on 8/8/19 through ehoopla