Piet Mondrian: Difference between revisions

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

* The [[Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals]] lists 2 articles [http://www.austheos.org.au/cgi-bin/ui-csvsearch.pl?search=Mondrian about Mondrian]. | * The [[Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals]] lists 2 articles [http://www.austheos.org.au/cgi-bin/ui-csvsearch.pl?search=Mondrian about Mondrian]. | ||

* Harris, Philip S. "Mondrian, Piet." ''Theosophical Encyclopedia'' (Quezon City, Philippines: Theosophical Publishing House, 2006), 542-543. Available at [http://theosophy.ph/encyclo/index.php?title=Mondrian,_Piet Theosopedia]. | * Harris, Philip S. "Mondrian, Piet." ''Theosophical Encyclopedia'' (Quezon City, Philippines: Theosophical Publishing House, 2006), 542-543. Available at [http://theosophy.ph/encyclo/index.php?title=Mondrian,_Piet Theosopedia]. | ||

* [http://www.khaldea.com/charts/mondrian.shtml Piet Mondrian Natal Horoscope] at Khaldea. | |||

* Welsh, Robert P. [http://www.theosophyforward.com/index.php/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/643-mondrian-and-theosophy-part-one.html "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part one."] ''Theosophy Forward''. September 27 2012. Viewed October 21, 2016. | * Welsh, Robert P. [http://www.theosophyforward.com/index.php/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/643-mondrian-and-theosophy-part-one.html "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part one."] ''Theosophy Forward''. September 27 2012. Viewed October 21, 2016. | ||

* Welsh, Robert P. [http://www.theosophyforward.com/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/686-mondrian-and-theosophy-part-two- "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part two."] ''Theosophy Forward'' December 10, 2010. Viewed October 21, 2016. | * Welsh, Robert P. [http://www.theosophyforward.com/theosophy-and-the-society-in-the-public-eye/686-mondrian-and-theosophy-part-two- "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part two."] ''Theosophy Forward'' December 10, 2010. Viewed October 21, 2016. | ||

Revision as of 21:25, 2 November 2016

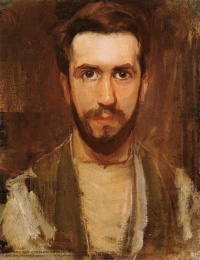

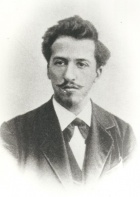

Pieter Cornelis "Piet" Mondrian (March 7, 1872 – February 1, 1944), was an influential Dutch painter, and one of the founders of the Dutch modern movement De Stijl.

Personal life

Early life and education

Piet Mondrian (originally spelled Mondriaan) was born on March 7, 1872 in the Dutch town of Amersfoort. His father and uncle taught him to draw and paint.

His artistic talent was fostered by his father, a confirmed Calvinist and a schoolmaster, with whom the young Mondrian collaborated in a series of historical paintings with a moralizing aim. In spite of this initial support, Mondrian was confronted with harsh opposition form his family when he decided to give up his career as an art professor and devote himself entirely to painting. In 1892, Mondrian enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam and entered that city's artistic circles. During the same period, he came into contact for the first time with esotericism, most notably with Theosophy, which would lead to his gradual estrangement from the Calvinist faith.[1]

Later years

In the early 1910s, Mondrian lived in Paris, in a studio in the rue du Départ. At the outbreak of the First World War, he was visiting the Netherlands, and was unable to return to Paris until 1919. After that the artist became very well known from his artistic production and the many articles he wrote for De Stijl to lay out his theory of art. In 1922 a retrospective exhibit of his work was held in Paris to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. As World War II approached in 1938, Mondrian moved to London, and two years later to New York. On February 1, 1944, he died of pneumonia there. He never married.

Artistic career

Mondrian was first employed as a primary school teacher, and also painted naturalistic landscapes. His early works employed soft, misty colors of the Dutch countryside, but around 1907 his palette expanded into stronger color schemes.

Transition away from naturalism

Woods Near Oele, painted in 1908, is representative of Mondrian's move toward abstraction.

This large canvas, whose subject has been identified... as the woods near the village of Oele... marks a milestone in the painter's work. It shows the phase of his art in which his horizon opened up and he began to look beyond the somewhat narrow boundaries of the Dutch school...

The painting itself is clearly a transitional work. On the one hand it belongs... to a period in which a scene of nature is brought to sober, almost solemn simplicity by means of rigorous stylization and stringent two-dimensional treatment. On the other hand, the color, the brushwork, and the rhythm of the painting betray a dynamism that indicates foreign influences...

The new view of reality, the realization that there are forces existing in nature related to those of human feeling and thought, stimulated Mondrian to attempt a fresh approach.[2]

Synthetic Cubism

The artist explored artistic styles like Luminism (also called Divisionism), Symbolism, and Suprematism, but in 1911 was drawn to the Cubism of Picasso and Braque. "In 1913, his work began to receive some recognition... the artist entered into a contract with the Kröller-Müllers, a family of famous industrialists, whereby he agreed to produce a certain number of paintings yearly in exchange for a stipend."[3] During the First World War, he stayed at the Laren artist's colony in The Netherlands, and there he met Theo van Doesburg, with whom he later founded a periodical, De Stijl.

"Mondrian developed his own individual notion of Synthetic Cubism, exhibiting a definite tendency toward full abstraction."[4] He radically simplified the elements of his paintings to reflect what he saw as the spiritual order underlying the visible world, creating a clear, universal aesthetic language within his canvases.

De Stijl and Neoplasticism

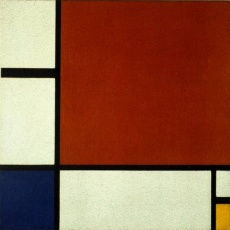

De Stijl developed as an artistic and architectural movement in The Netherlands, from about 1917 to 1931. The artists aimed for pure abstraction rather than representation. They reduced the color palette to black, white, gray, and primary colors. Mondrian developed a form that he called neoplasticism, in horizontal and vertical configurations of squares and rectangles. He was influenced by M. H. J. Schoenmaekers, a Theosophist and mathematician, who wrote in a 1915 essay:

The two fundamental and absolute extremes that shape our planet are: on the one hand the line of the horizontal force, namely the trajectory of the Earth around the Sun, and on the other vertical and essentially spatial movement of the rays that issue from the center of the Sun... the three essential colors are yellow, blue, and red. There exist no other colors besides these three.[5]

Mondrian published his own theory as "De Nieuwe Beelding in de schilderkunst" in twelve installments over 1917 and 1918. He moved to Paris and began work on the grid-based paintings for which he has become best known, with gray or black lines as structure for blocks of white, gray, and primary colors. His association with Van Doesburg ended in 1925, "when the latter adopted the diagonal line in pursuit of what he labeled Elementarism. This Mondrian regarded as a betrayal of their shared aesthetic principles.[6]

New York years

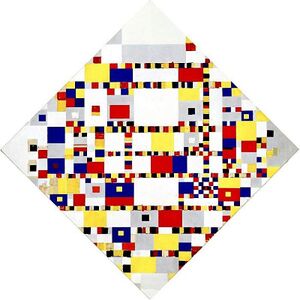

When World War II broke out, Mondrian left continental Europe for London. In 1940 he took up residence in New York City. He loved the city - particularly its architecture and its modern music. His final two paintings celebrated the pulsing rhythms of jazz. In Broadway Boogie-Woogie, the artist moved away from outlining the colored spaces with black, giving a more open effect. Small segments of colors were distributed in patterns evoking syncopation or staccato. Victory Boogie-Woogie was not quite completed when the artist died, but it framed the horizontal and vertical lines in a rhombus or "lozenge" shape.

Theosophical Society involvement

In 1908 Piet Mondrian became interested in the Theosophical Society, and in May 2009 became a member of the Dutch Section. The Society's founder, Madame Blavatsky, believed that it was possible to attain a knowledge of nature more profound than that provided by empirical means, and much of Mondrian's work for the rest of his life was inspired by his search for that spiritual knowledge. In addition to Blavatsky's writings, he is known to have read works by Édouard Shuré (Les Grands Inities) and by Rudolf Steiner.[7]

Symbolist works

While Mondrian was still experimenting with Symbolist art, he painted Evolution, a triptych that made use of mystical triangles, hexagons, and Stars of David. The images, read from left to right, depict a movement from the material to the spiritual, a common concept in Theosophy. This work is one of few painted during Mondrian's foray into Symbolism. He was attempting to present the essential reality, regarding the artist as an initiate intermediating for the public, but soon he moved away from use of symbols into a purely abstract and universalist mode of expression.

Theosophical influence on Neoplasticism

Theosophical concepts pervaded Mondrian's development of Neoplasticism:

He was most concerned with cosmic harmony, which was to be expressed in a correct balance between general and abstract elements representative of absolute truth and absolute beauty. These elements, or "vibrations of energy," are either male, equated to the vertical and to direction, and visually represented by the line; or female, the horizontal and space, represented by the field and color. In The Secret Doctrine the male vertical line, or active and moving spirit (designated by the Sanskrit term purusha), and female horizontal field, or cosmic space or matter (prakriti), are posited to be in mutual opposition, while at the same time being facts of the Absolute or One. the joining of male and female is represented by the cross or right angle.[8]

Biographer Michel Seuphor wrote, "Calvinism was first engulfed by Theosophy, and then Theosophy was absorbed by Neo-Plasticism, which was left with the task to express it all without words."[9]

Published collections and exhibit catalogs

- Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art, 1937, and Other Essays, 1941-1943. New York: Wittenborn and Co., 1945.

- Piet Mondrian. New York: Sidney Janis Gallery, 1951.

- Mondrian and his Studios: Colour in Space. Liverpool: Tate Gallery, Liverpool: 2015. Exhibition Catalogue.

Other Resources

- Bax, Marty. "'Character Is Destiny' - Piet Mondrian and his horoscope." Bax Art Concepts & Services blog. March 7, 2013. Available at Baxpress.blogspot. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Bax, Marty. Complete Mondrian. Burlington, VT: Lund Humphries, 2001.

- Bax, Marty. "The Victory Boogie Woogie - a corpse dissected." Bax Art Concepts & Services blog. April 4, 2012. Baxpress.blogspot. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Bris-Marino, "The influence of Theosophy on Mondrian’s neoplastic work" "La influencia de la teosofía sobre la obra neoplástica de Mondrian".

- The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 2 articles about Mondrian.

- Harris, Philip S. "Mondrian, Piet." Theosophical Encyclopedia (Quezon City, Philippines: Theosophical Publishing House, 2006), 542-543. Available at Theosopedia.

- Piet Mondrian Natal Horoscope at Khaldea.

- Welsh, Robert P. "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part one." Theosophy Forward. September 27 2012. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Welsh, Robert P. "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part two." Theosophy Forward December 10, 2010. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Hall, Kathleen. "Theosophy and the Emergence of Modern Abstract Art" The Quest 90.3 (May-June 2002).

Notes

- ↑ José Marίa Faerna, General Editor. Great Modern Masters: Mondrian (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), 7.

- ↑ Piet-Mondrian.org.

- ↑ José Marίa Faerna, General Editor. Great Modern Masters: Mondrian (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), 7-8.

- ↑ José Marίa Faerna, General Editor. Great Modern Masters: Mondrian (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), 7.

- ↑ José Marίa Faerna, General Editor. Great Modern Masters: Mondrian (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), 34. Quoted from essay "The New Image of the World." See also page 8.

- ↑ José Marίa Faerna, General Editor. Great Modern Masters: Mondrian (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997), 8.

- ↑ Robert P. Welsh "Mondrian and Theosophy – Part one." Theosophy Forward. September 27 2012. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- ↑ Tessel M. Bauduin, "Abstract Art as 'By-Product of Astral Manifestation': The Influence of Theosophy on Modern Art in Europe" Handbook of the Theosophical Current (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 432-433.

- ↑ Michel Seuphor, Piet Mondrian, sa vie, son oeuvre. Paris: Flammarion, 1986.