Hilma af Klint: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

* Bax, Marty. "Hilma and the Enigmatic Mathilde N." Bax Art Concepts & Services blog. October 4, 2013. Available at [http://baxpress.blogspot.nl/2013/10/hilma-and-enigmatic-mathilde-n.html#more Baxpress.blogspot]. Viewed October 21, 2016. | * Bax, Marty. "Hilma and the Enigmatic Mathilde N." Bax Art Concepts & Services blog. October 4, 2013. Available at [http://baxpress.blogspot.nl/2013/10/hilma-and-enigmatic-mathilde-n.html#more Baxpress.blogspot]. Viewed October 21, 2016. | ||

* [http://www.telegraph.co.uk/luxury/art/hilma-af-klint-painting-the-unseen-at-the-serpentine/ Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen at the Serpentine] by Louisa Buck for The Telegraph. | * [http://www.telegraph.co.uk/luxury/art/hilma-af-klint-painting-the-unseen-at-the-serpentine/ Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen at the Serpentine] by Louisa Buck for The Telegraph. | ||

* Bashkoff, Tracey. Hilma af Klint: paintings for the future. New York, NY: Guggenheim Museum, 2018. Print. | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 29 October 2018

Hilma af Klint, (October 26, 1862 – October 21, 1944) was a Swedish artist and mystic whose paintings were amongst the first abstract art. A considerable body of her abstract work predates the first purely abstract compositions by Wassily Kandinsky.

Early Life and Education

Hilma af Klint was born in Sweden on October 26 1862, the fourth child of Captain Victor af Klint, a Swedish naval commander, and Mathilda af Klint (née Sonntag).

At an early age she showed signs of artistic aptitude, though her true interests included mathematics and botany. When the family moved to Stockholm, af Klint studied at the Academy of Fine Arts of Stockholm, where she learned portraiture and landscape painting. At the age of 20, she was admitted to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and during the years of 1882–1887 she studied mainly drawing, portrait and landscape painting. She graduated with honors and was given studio space in the Atelier Building as a scholarship. Hilma af Klint began working in Stockholm, gaining recognition for her landscapes, botanical drawings, and portraits, providing a source of income.

Artistic Career

The Five

Around the age of seventeen, af Klint became involved in spiritualism. She became interested in Theosophy and the philosophy of Christian Rosenkreutz, then later anthroposophy developed by Rudolf Steiner.

While at the Academy of Fine Arts, af Klint met Anna Cassell who would be one of the four women in her group called the Five (de Fem). Between 1896 to 1906, the spiritualist group made up of female artists, would gather on Fridays and conduct seances to connect with the spiritual realm. The women would carefully record what happened during their meetings in notebooks.

As Jochen Volz, General Director of the museum Pinacotea de Sao Paul in Brazil and curator of show, “Hilma af Klint: Mundos Possíveis (Hilma af Klint: Possible Worlds)” wrote:

“They would always start with a prayer or song, then read a certain sequence from the New Testament and discuss it. Then they would get into a state of consciousness where they could communicate with higher spirits, who they called ‘The High Masters (Höga Mästare)’.”[1]

During their seances, the Masters would present themselves by name and promise to help the group in their spiritual training. Over the years, af Klint functioned as the sole medium of the group. She would create automatic drawings, a practice that would be popular amongst Surrealists in the 1920s. Af Klint’s hand would move automatically and without her will, making her an artistic tool for the group’s spirit leaders. She was constantly surprised by the result of her unconscious activities and would be unable to explain them.

After years of these seances with the Five, af Klint accepted a major assignment from one of the Masters, the Paintings for the Temple. This commission, in which she would be engaged between 1906 and 1915, would change the course of her life.

Paintings for the Temple

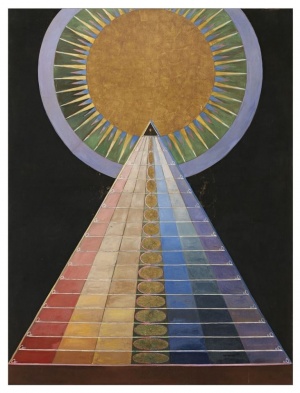

In 1906, af Klint received a commission from one of the High Masters. These series of abstract paintings would be known as Paintings for the Temple, though admittedly she never understood what the Temple actually referred to. It is one of the very first pieces of abstract art in the Western world, as it predates by several years the first non-figurative compositions of her contemporaries in Europe.[2]

The creation of Paintings for the Temple was carried out in two phases between 1906-1915, with an interruption between 1908 to 1912. The series contained 193 paintings, grouped in several series and subseries. She explained that the pictures were painted “through” her with “force” – a divine dictation: “I had no idea what they were supposed to depict…I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”[3]

The major paintings, dated 1907, are extremely large in size. Aptly called The Ten Largest, each painting of the series measures approximately 240 cm x 320 cm describing different phases of life, from early childhood to old age. The paintings often depict symmetrical dualities (up and down, in and out, good and evil), while her color choice should be seen as metaphorical.

Once the whole series was completed in 1915, af Klint claimed she ceased to receive guidance from the High Masters. However, she continued with abstract painting, independently from any external influence.

Later Works

Later paintings were significantly smaller in size. She painted, among others, a series depicting the stand-points of different religions at various stages in history, as well as representations of the duality between the physical being and its equivalence on an esoteric level. As Hilma af Klint pursued her artistic and esoteric research, it is possible to perceive a certain inspiration from the artistic theories developed by the Anthroposophical Society from 1920 onward.[4]

In June 1922 she took up painting again but in a more explicitly anthroposophical way, using soft watercolors flowing into each other without any underlying drawing. She returned to her interest in botany, working with plants, with titles of her watercolors such as Looking at the Rose Hip II and Looking at Mallow.[5]

Theosophical Society Involvement and Influence of Theosophy

Hilma af Klint shared an interest in the spiritual with other contemporary pioneers in abstract art such as Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian, all wishing to surpass the restrictions of the physical world. Not surprisingly, many were drawn to Theosophy, as its ideas proposed an attractive alternative to the very static principles of academic art.[6]

On May 23, 1904, af Klint joined the Stockholm Lodge of the Theosophical Society headquartered in Adyar, Chennai, India.[7] There is evidence that she participated in a Swedish lodge as early as 1889, but little is known about her early involvement. She was soon immersed in varied reading of Christian and esoteric literature. Her library included, in Swedish translation, Helena Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, Annie Besant’s Esoteric Christianity, Franz Hartmann’s Magic Black and White and the German philosopher Baron Carl du Prel’s early study on mysticism and altered states of consciousness.[8]

Af Klint had a very specific creative technique, working through a dialogue between the unconscious and the conscious, and her knowledge of occult texts may have been a subliminal influence that led her to inspired mediumistic messages as well as to her later, more conscious work. For example, af Klint was evidently inspired by the evolutionary theories of Helena P. Blavatsky, but she transformed them in her art.[9]

Exhibitions (posthumous)

All through her life, Hilma af Klint would seek to understand the mysteries that she had come in contact with through her work. She left behind more than 150 notebooks with her thoughts and studies.[10]

Hilma af Klint died on October 21, 1944, five days before her 82nd birthday, due to injuries sustained during a traffic collision.

Rarely exhibited, af Klint’s work was never seen by the public eye. At the time of her death, she believed that the world was not ready for her art, thinking it too forward-looking. In her will, af Klint left all her abstract paintings to her nephew, specifying that her work would be kept secret 20 years after her death. When the boxes were opened at the end of the 1960s, very few people had knowledge of what would be revealed. In 1970, after her work was finally revealed by her family, it was offered as a gift to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, but they declined the donation.

It wasn’t until 1984, when art historian Åke Fant presented af Klint’s pieces at a conference in Helsinki that her work was finally recognized. Today, there are more than 1,200 of af Klints works, including 150 notebooks (some containing over 26,000 pages) at the Hilma af Klint Foundation in Stockholm, Sweden. In 2017, Norwegian architectural firm Snøhetta, presented plans for an exhibition centre dedicated to af Klint in Järna, south of Stockholm. In February 2018, the Foundation signed a long-term agreement of cooperation with the Moderna Museet, thereby confirming the perennity of the Hilma af Klint Room, i.e. a dedicated space at the museum where a dozen works of the artist are shown on a continuous basis.[11]

In Europe, Stockholm’s 2013 exhibition, Pioneer of Abstraction, was the most popular exhibition the Moderna Museet had ever held. London’s Serpentine Gallery exhibition, Painting the Unseen, showcased selections from the Paintings for the Temple, the Ten Largest (eight were shown). These pictures, oils and tempera on paper, are more than 10 feet tall: free-wheeling, psychedelic, animated with fat snail shells, perky inverted commas, unspooling threads, against orange, rose and dusky blue.[12]

In the U.S., the work of Hilma af Klint was first shown in 1986 organized by Maurice Tuchman in Los Angeles. Making her international debut, the exhibition, The Spiritual in Art, Abstract Painting 1890–1985, was the starting point of her international recognition.

From October 12, 2018, to February 3, 2019, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, New York will present the first major U.S. solo exhibition of af Klint, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future. The exhibit explores how Theosophy and other esoteric belief systems that became popular during the turn of the 20th century impacted the development of abstraction in the United States and Europe and promises to feature more than 170 works of art and focus on the artist’s breakthrough years, 1906-1920. It is during this period that she began to produce non-objective and stunningly imaginative paintings, creating a singular body of work that invites a reevaluation of modernism and its development.[13]

Additional resources

- Seven articles about Hilma af Klint are listed in the Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals.

- "Art and About: Hilma af Klint".

- Bax, Marty. "Hilma and the Enigmatic Mathilde N." Bax Art Concepts & Services blog. October 4, 2013. Available at Baxpress.blogspot. Viewed October 21, 2016.

- Hilma af Klint: Painting the Unseen at the Serpentine by Louisa Buck for The Telegraph.

- Bashkoff, Tracey. Hilma af Klint: paintings for the future. New York, NY: Guggenheim Museum, 2018. Print.

Notes

- ↑ Rosen, Miss. "This Swedish Woman Created Some Of The World's First Abstract Paintings-And Then Hid Them Away For Decades." BUST, June/July 2018, bust.com/arts/194718-hilma-af-klint-abstract-art.html. Accessed 12 Oct 2018.

- ↑ “Hilma af Klint.” Hilma af Klint, https://www.hilmaafklint.se/about-hilma-af-klint. Accessed 8 Oct. 2018.

- ↑ Kellaway, Kate. “Hilma af Klint: a painter possessed.” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/21/hilma-af-klint-occult-spiritualism-abstract-serpentine-gallery. Accessed 5 Oct 2018.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "Hilma af Klint." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sep. 2018. Web. 10 Oct. 2018.

- ↑ Fant, Ake, et al.Spiritual in art: abstract painting 1890-1985. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986.

- ↑ “Hilma af Klint.” Hilma af Klint, https://www.hilmaafklint.se/about-hilma-af-klint. Accessed 8 Oct. 2018.

- ↑ Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 2, entry 25914 (website file: 2C/66).

- ↑ Lochnan et al, Mystical landscapes: from Vincent van Gogh to Emily Carr (Munich : DelMonico Books Prestel 2017), 295.

- ↑ Fant, Ake, et al. Spiritual in art: abstract painting 1890-1985. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "Hilma af Klint." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sep. 2018. Web. 10 Oct. 2018.

- ↑ Wikipedia contributors. "Hilma af Klint." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sep. 2018. Web. 10 Oct. 2018.

- ↑ Kellaway, Kate. “Hilma af Klint: a painter possessed." The Guardian. Last modified February 21, 2016. Accessed October 9, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/21/hilma-af-klint-occult-spiritualism-abstract-serpentine-gallery.

- ↑ Guggenheim. “Guggenheim Museum Presents Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future." Guggenheim. Last modified September 13, 2018. Accessed October 9, 2018. https://www.guggenheim.org/press-release/guggenheim-museum-presents-hilma-af-klint-paintings-for-the-future.