Radiant Matter: Difference between revisions

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Pablo Sender (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

<blockquote>But what is in reality Matter? We have seen that it is hardly possible to call electricity a force, and yet we are forbidden to call it matter under the penalty of being called unscientific! . . . And, as Professor Crookes has now succeeded in refining gases to a condition so ethereal as to reach a state of matter “fairly describable as ultra-gaseous, and exhibiting an entirely novel set of properties,” why should the Occultists be taken to task for affirming that there are beyond that “ultra gaseous” state still other states of matter; states, so ultra refined, even in their grosser manifestations—such as electricity under all its known forms—as to have fairly deluded the scientific senses, and let the happy possessors thereof call electricity—a Force!<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. IV (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1991), 221-222.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>But what is in reality Matter? We have seen that it is hardly possible to call electricity a force, and yet we are forbidden to call it matter under the penalty of being called unscientific! . . . And, as Professor Crookes has now succeeded in refining gases to a condition so ethereal as to reach a state of matter “fairly describable as ultra-gaseous, and exhibiting an entirely novel set of properties,” why should the Occultists be taken to task for affirming that there are beyond that “ultra gaseous” state still other states of matter; states, so ultra refined, even in their grosser manifestations—such as electricity under all its known forms—as to have fairly deluded the scientific senses, and let the happy possessors thereof call electricity—a Force!<ref>Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, ''Collected Writings'' vol. IV (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1991), 221-222.</ref></blockquote> | ||

== Notes == | |||

<references/> | |||

==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

*[http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_16/November_1879/On_Radiant_Matter_I# On Radiant Matter by W. Crookes] at Wikisource | *[http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_16/November_1879/On_Radiant_Matter_I# On Radiant Matter by W. Crookes] at Wikisource | ||

Revision as of 19:51, 27 June 2012

Radiant Matter is the term used to describe what British physicist William Crookes believed was a fourth state of matter, in a time when the atom was thought to be a small solid ball, indivisible and without motion. Crookes's experimental work in this field was the foundation of discoveries which eventually changed the whole of chemistry and physics.

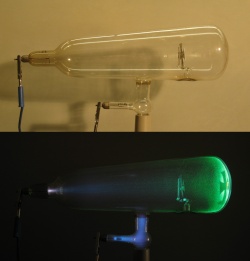

Crookes tubes

By the 1870s the nature of electricity was unknown, and many experiments were done to determine its nature. Tubes with a low vacuum, possessing two metal electrodes (one at either end) were commonly employed for this purpose. When a high voltage was applied between the electrodes, a glow filling the tubes was observed. This glow was said to be the effect of "cathode rays."

William Crookes was able to generate a higher vacuum in tubes (known as "Crookes Tubes") and found out that as he pumped more air out of the tubes, they became totally dark, except for the anode end, where the glass of the tube itself began to glow. This showed that the cathode rays travel in straight lines from the cathode (negative) end to the anode (positive), causing fluorescence in objects upon which they impact and producing great heat.

At the time there were two theories to explain the nature of the cathodic rays. Heinrich Hertz and others believed they were "aether waves," while Crookes insisted they were formed by particles. He maintained they were a fourth state of matter where atoms were electrically charged. The debate was resolved in 1897 when Sir J. J. Thomson established the particle-nature of the rays. However, he discovered they were not atoms, but a new particle (the first subatomic particle to be discovered) which was named "electron". Thus, Thomson proved that the cathode rays are streams of electrons.

The Crookes tubes were used in many historic experiments. For example, in 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered the X-rays emanating from Crookes tubes. Eventually, these tubes were superseded by the electronic vacuum tubes, in whose development Thomas Edison played an important role.

Blavatsky on radiant matter

H. P. Blavatsky maintained that Crookes' discovery of "radiant matter" proved that there exist more refined states of matter (or particles) than the "solid atoms" of her time. She argued that electricity was not an immaterial force, but a form of matter (later know as the electron) which does not have the properties assigned to "dense matter":

But what is in reality Matter? We have seen that it is hardly possible to call electricity a force, and yet we are forbidden to call it matter under the penalty of being called unscientific! . . . And, as Professor Crookes has now succeeded in refining gases to a condition so ethereal as to reach a state of matter “fairly describable as ultra-gaseous, and exhibiting an entirely novel set of properties,” why should the Occultists be taken to task for affirming that there are beyond that “ultra gaseous” state still other states of matter; states, so ultra refined, even in their grosser manifestations—such as electricity under all its known forms—as to have fairly deluded the scientific senses, and let the happy possessors thereof call electricity—a Force![1]

Notes

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. IV (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1991), 221-222.

Further reading

- On Radiant Matter by W. Crookes at Wikisource