Jakob Böhme: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Accessed on 5/25/20</ref></br> | Accessed on 5/25/20</ref></br> | ||

<br>The record of Boehme’s reception is a sequence of verdicts: hereticized or vindicated in the seventeenth century, shunned by the Enlightenment, rehabilitated by the Romantics, Boehme in this century has been reclaimed as a cultural nationalist by national-minded Germans, as a Lutheran by Lutheran church historians, and as fund of universal myth by | <br>The record of Boehme’s reception is a sequence of verdicts: hereticized or vindicated in the seventeenth century, shunned by the Enlightenment, rehabilitated by the Romantics, Boehme in this century has been reclaimed as a cultural nationalist by national-minded Germans, as a Lutheran by Lutheran church historians, and as fund of universal myth by Jungians or New Age enthusiasts. <ref>Weeks, Andrew. <i>Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher.</i> State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 5.</ref></br> | ||

==Early Years== | ==Early Years== | ||

Revision as of 16:57, 12 October 2020

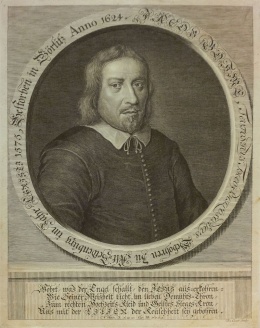

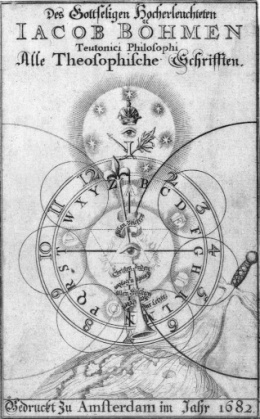

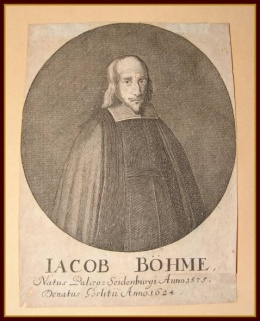

Jacob Boehme (1575 – 1624) has been called a philosopher, a Christian mystic, a Lutheran Protestant theologian, a Christian Theosophist, and a spiritualist. Boehme fits no one of these categories entirely, and yet he overlaps all of them. [1]Boehme has gained the cognomen Philosophus Teutonicus, called himself the “Philosophus der Einfältigen,” (the philosopher of the simple folk)[2]and Hegel called him the “first German philosopher,” because he was the first to publish philosophical writings in German. [3]

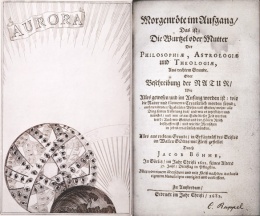

He was considered an original thinker by many of his contemporaries within the Lutheran tradition, and his first book, commonly known as Aurora, caused a great scandal. In contemporary English, his name may be spelled Jacob Boehme; in seventeenth-century England it was also spelled Behmen, approximating the contemporary English pronunciation of the German Böhme.[4]

The record of Boehme’s reception is a sequence of verdicts: hereticized or vindicated in the seventeenth century, shunned by the Enlightenment, rehabilitated by the Romantics, Boehme in this century has been reclaimed as a cultural nationalist by national-minded Germans, as a Lutheran by Lutheran church historians, and as fund of universal myth by Jungians or New Age enthusiasts. [5]

Early Years

Jacob Boehme was born the fourth of five children [6]in 1575 (probably on April 24th [7]) of poor peasant parents at Alt-Seidenberg (now Stary Zawidow,

Poland), a village near the small city of Görlitz, Germany. The population numbered less than 10,000 at the time. [8][9]

Boehme herded cattle for his parents in his youth [10]

but he was also grave and thoughtful beyond his years as a child, was a diligent student of the Bible, but did not like dogmatic interpretations. He also read mystical and astrological books. In his first book Aurora he mentions astrology; excerpts of writings by Paracelsus can be found in this book as well. [11]

After a solid primary education, he was apprenticed to a shoemaker. After his journeyman years he settled in Görlitz in 1592. In 1599 he acquired citizenship and married Katharina Kuntzschmann, a butcher’s daughter. They bought a house and he opened a shoemaker’s shop. Their first child was born in 1600, and they had three more sons, one of them died. In 1612 Boehme left shoemaking to become a yarn merchant. [12][13]

Spiritual Experiences

It seems that even in his early youth he was able to enter into an abnormal state of consciousness and to behold images in the astral light. Once, while herding the cattle and standing on the top of a hill, he suddenly saw an arched opening of a vault, built of large red stones, and surrounded by bushes. He went through that opening into the vault, and in its depths, he beheld a vessel filled with money. He had no desire to possess that treasure and fled. [14]

He had another unusual experience when he worked in the shoemaker's shop and an unknown stranger entered and asked Boehme to come outside. When he went out in the street the stranger looked into his eyes and said: “Jacob, you are now little; but you will become a great man, and the world will wonder about you. Be pious, live in the fear of God, and honor His word. Especially do I admonish you to read the Bible; herein you will find comfort and consolation; for you will have to suffer a great deal of trouble, poverty, and persecution. Nevertheless, do not fear, but remain firm; for God loves you, and is gracious to you." [15]One of his biographers, Abraham von Franckenberg, was profoundly impressed by the fact that so many like-minded spirits had succeeded in joining together as a kind of secret informal brotherhood at that time. He thought the incident providential in that it suggests an early personal conflict between inner and external authority. [16]

In Boehme’s age inspiration came often by way of a divine flash. [17] Boehme’s own mystical journey began when he had a spiritual vision while travelling for business. He felt himself, as he described the occurrence, "surrounded with a divine light, and stood in the highest contemplation and kingdom of joys." ."[18]This condition lasted for seven days, during which time he was enveloped in an atmosphere of spiritual glory, which in no way impeded him in his daily manual labor, but, he said, "The triumph that was then in my soul I can neither tell nor describe. I can only liken it to a resurrection from the dead." [19][20] He also said:

I learned what God is, and what is his will….. I knew not how this happened to me, but my heart admired and praised the Lord for it!”[21]

In the year 1600 he had begun to prosper being a careful and serious workman. [22]That year, about five years after his first vision, he had another spiritual experience, which one of his biographers described as follows:

Sitting one day in his room his eye fell upon a burnished pewter dish which reflected the sunshine with such marvelous splendor that he fell into an inward ecstasy, and it seemed to him as if he could now look into the principles and deepest foundations of things. He believed it was only a fancy, and in order to banish it from his mind he went out upon the green. But here he remarked that he gazed into the very heart of things, the very herbs and grass, and that actual nature harmonized with what he had inwardly seen. He said nothing about this to anyone, but praised and thanked God in silence. He continued in the honest practice of his craft, was attentive to his domestic affairs, and was on terms of good will with all men.[23][24]

From this experience he continued looking for answers about the interconnection of all things with God, seeking answers for how evil exists in a good creation. [25]

Ten years afterwards, anno 1610, his third illumination took place. He recognized the divine order of nature, and how from the trunk of the tree of life spring different branches, bearing manifold leaves and flowers and fruits. [26][27]

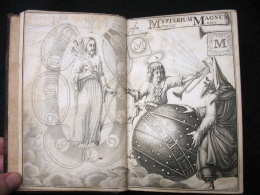

His writings

After his last spiritual vision, he felt an inward yearning to write everything down, mainly for himself. The work that sprang from this was his famous Morning Redness, re-titled by a friend to Aurora[28]This work was not quite finished, when, by the indiscretion of a friend, copies of the manuscript came into the hands of the parish clergyman, Gregorius Richter. [29]He was a man full of hierarchical arrogance, had only an outward apprehension of the dogmatics of that time. [30] The priest accused Boehme of being a disturber of the peace and a heretic, asking the City Council of Goerlitz to punish him. The City Council was afraid of the priest, and, although the members could not substantiate any charge against Boehme, stipulated that he should give up to them the manuscript of the "Aurora" and abstain from the writing of books. [31]

For several years Boehme remained silent but started his second book around the beginning of 1618, on the eve of the Thirty Years’ War, which took nearly two years to finish and was followed by an unceasing stream of writing. During the first years of the devastating war, his writings were copied and circulated by hand. By his death in 1624, Boehme’s reputation was already established in several areas of North Germany. [32]

Boehme wrote "The Threefold Life of Man", "Forty Questions on the Soul", "The Incarnation of Jesus Christ", "The Six Theosophical Points", "The Six Mystical Points" in 1620. In 1621 he wrote "De Signatura Rerum" and in 1623 "On Election to Grace", "On Christ's Testaments", "Mysterium Magnum", and "Clavis (Key)". [33]

His Teachings

The mystical doctrines of Boehme are remarkable for the profundity of their concepts and for the obscurity and complexity of their terminology in which these concepts are set forth since he was not very educated. Boehme was forced to grope for words and frequently the selection of terms was unfortunate. The spiritual experiences came to him internally and were outside the boundaries of written words. [34]

Boehme’s teachings were founded in personal piety and devotion. He discovered a sufficient and sustaining internal extension of consciousness, moving irresistibly toward the substance of the Universal Reality. [35]

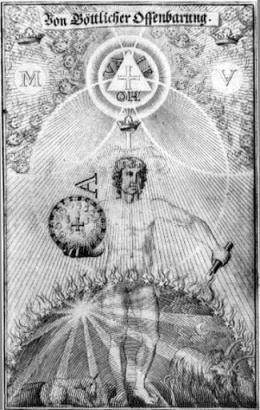

Jakob Boehme’s cosmology is based on the idea that everything which exists is ruled by a very small number of general laws. Boehme presented this in a strict, formal schematic diagram, which he proposed as an interpretation of the entire cosmos, and even of God himself. The conceptual plan is based on the interaction between a threefold logic or structure and a sevenfold, self-organizing cycle or process. [36]

Boehme’s doctrine of good and evil is one of the most important parts of his work. His thought is based on a logic of contradictories, as one of his essential ideas is the unity of opposites. God himself is the incarnation of this unity of opposites. [37] He says:

“I acknowledge a universal God, being a Unity, and the primordial power of Good in the universe; self-existent, independent of forms, needing no locality for its existence, unmeasurable and not subject to the intellectual comprehension of any being. I acknowledge this power to be a Trinity in One, each of the Three being of equal power, being called the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. I acknowledge that this triune principle fills at one and the same time all things; that it has been, and still continues to be, the cause, foundation, and beginning of all things. I believe and acknowledge that the eternal power of this principle caused the existence of the universe ; that its power, in a manner comparable to a breath or speech (the Word, the Son or Christ), radiated from its center, and produced the germs out of which grow visible forms, and that in this exhaled Breath or Word (the Logos) is contained the inner heaven and the visible world with all things existing within them.”

Moreover, he taught that to be a true Christian it was not sufficient to subscribe to a certain set of beliefs; but that only he in whom the Christ is living is a true follower of Christ in spirit and in truth. [38]

In his book “Six Theosophic Points” Boehme starts with the “first growth of life from the first principle” and writes about the springing of the three Principles; he continues with the mixed tree of good and evil, the tree of life; how a life may perish in the tree of life; and the life of darkness and the devil. He writes:

"Nor have I ascended into heaven, nor have I seen all the works and creations of God, but heaven has revealed itself within the spirit in such a way that I there recognize the divine works and creations. By my own powers I am as blind as the next man, but through the spirit of God, my own inborn spirit pierces all things..."[39]

He lived in the most violent and disturbed times, between the civil wars of the 16th century and the disastrous Thirty Years' War that drained the very heart of Europe. Through the meeting and dealing with all types of human beings as they came to his shop, and as they met in church and in ordinary daily circumstances, he came to apprehend the underlying causes that had brought such depths of misery upon his people. [40] To him, there was only one sure way for man to go, and that was "to seek that which is lost." But to set ourselves in the true direction, "we need no flattering Hypocrites, nor such as tickle our ears to comfort us, and promise us many Golden Mountains if we will but run after them, and make much of them, and reverence them." Nor should we do as the "high and learned" who think they must "set the University before their eyes (as a pair of Spectacles), and study first with what opinion they will enter into the Temple of Christ." [41] No, he added, neither the opinion of Luther, nor of Calvin, not even of the Pope, will avail before God "who is within and not without." [42]

He addressed his readers often in the preface of his books and in the introduction to one of his books we can read as follows:

God-loving reader! If it is your earnest and serious will and desire to devote yourself to that which is divine and eternal, the reading of this book will be very useful to you; but if you are not fully determined to enter the way of holiness, it would be better for you to let alone the sacred names of God, wherein his supreme sanctity is invoked; because the wrath of God may become ignited within your soul. This book is written only for those who desire to be sanctified and united with the supreme power from which they have originated. Such persons will understand the true meaning of the words contained therein, and they will also recognize the source from which these thoughts have come. [43]

Boehme’s Last Year

A time of great suffering began for Jacob Boehme in March, 1624 - shortly before his death. In 1623, Abraham von Frankenburg had some of Boehme's works published under the title of "The Way to Christ." and the appearance of this book, again inflamed the rage of the angry parson of Goerlitz, who was upset about how well the book was received. Gregorius Richter began again his persecutions of Jacob Boehme, damning him from the pulpit, and published against him a pasquillo, full of personal insults and vulgar epithets. [44]

This time however Boehme published a written defense to the magistrates against the accusations and wrote a pamphlet against Richter in which he refutes his libel. The magistrate notified him that he had made himself liable to be treated as a heretic by the Emperor and recommended exile. He left after two months for Dresden where eventually a conference took place between Boehme and several eminent theologians which in the end declared themselves incompetent to judge Boehme. [45]

Boehme died on November 17, 1624, as he had lived in quite humble circumstances and surroundings, earning, to some extent, his daily bread by the work of his hands, but he received also, from some of his wealthy friends, enough to keep him from want. He had made many friends among the educated and well-born men with whom he corresponded, and who visited and looked up to him with affection as a teacher of unbounded resources on psychical and philosophical subjects. Among his followers were several alchemists and students of the "occult sciences." [46]

He died surrounded by his family, his last words being “Now I go hence into Paradise”. [47] His last words indicated a complete certainty as to the security of his future state. He lived without fear, and died without fear, accepting all the burdens of his years with a patient humility, obviously entirely sincere. Even though the second half of his life was considerably burdened by his sense of responsibility for the preservations of his revelations, he seems to have functioned without unreasonable or unusual pressures from within himself. [48]His friends cherished the saying which Boehme customarily inscribed in their guest registries:

For whom time is like eternity

An eternity is like time

He is free

of all adversity.[49]

Interestingly, Gregorius Richter died before Boehme in August 1624 and he lamented before his death that one of his sons had become a zealous adherent of Boehme and had transcribed and circulated his writings. [50]

Theosophists about Boehme

H. P. Blavatsky wrote that he was "the nursling of the genii (Nirmânakâyas) who watched over and guided him".[51] In her Theosophical Glossary, she added:

Boehme (Jacob). A great mystic philosopher, one of the most prominent Theosophists of the mediaeval ages. He was born about 1575 at Old Seidenburg, some two miles from Görlitz (Silesia), and died in 1624, at nearly fifty years of age. In his boyhood he was a common shepherd, and, after learning to read and write in a village school, became an apprentice to a poor shoemaker at Görlitz. He was a natural clairvoyant of most wonderful powers. With no education or acquaintance with science he wrote works which are now proved to be full of scientific truths; but then, as he says himself, what he wrote upon, he “saw it as in a great Deep in the Eternal”. He had “a thorough view of the universe, as in a chaos”, which yet “opened itself in him, from time to time, as in a young plant”. He was a thorough born Mystic, and evidently of a constitution which is most rare; one of those fine natures whose material envelope impedes in no way the direct, even if only occasional, intercommunion between the intellectual and the spiritual Ego. It is this Ego which Jacob Boehme, like so many other untrained mystics, mistook for God; “Man must acknowledge,” he writes, “that his knowledge is not his own, but from God, who manifests the Ideas of Wisdom to the Soul of Man, in what measure he pleases.” Had this great Theosophist mastered Eastern Occultism he might have expressed it otherwise. He would have known then that the “god” who spoke through his poor uncultured and untrained brain, was his own divine Ego, the omniscient Deity within himself, and that what that Deity gave out was not in “what measure he pleased,” but in the measure of the capacities of the mortal and temporary dwelling IT informed.[52]

William Q. Judge wrote that might truth came from the mind and out of the mouth of this unlettered man. He added:

His life and writings furnish another proof that the great wisdom-religion — the Secret Doctrine — has never been left without a witness. Born a Christian, he nevertheless saw the esoteric truth lying under the moss and crust of centuries, and from the Christian Bible extracted for his purblind fellows those pearls which they refused to accept. But he did not get his knowledge from the Christian Scriptures only. Before his internal eye the panorama of real knowledge passed. His interior vision being open he could see the things he had learned in a former life, and at first not knowing what they were, was stimulated by them to construe his only spiritual books in the esoteric fashion. His brain took cognizance of the Book before him, but his spirit aided by his past, and perchance by the living guardians of the shining lamp of truth, could not but read them aright.[53]

Franz Hartmann wrote that Boehme’s favorite motto was “Our salvation is in the life of Jesus Christ in us.” Hartmann said:

This alone is sufficient to show the true character of the Christianity of Boehme, who did not look for salvation from a dead and historical person, but from the living Jesus, made alive by the Christ within himself; or to express it in other terms, by the higher Manas (the mind) becoming self-conscious in the light of the Atma-Buddhi (the spiritual soul). [54]

Patience Sinnett wrote:He lived so simply, moved about so little, asserted himself so rarely, was so poor and of such humble birth, that in glancing back at the course of events the wonder is that either his writings or his personality should have ever emerged from the obscurity in which they had their origin. The explanation may probably be found in the fact that four centuries ago, as now, the man or woman whose psychic faculties were developed was sure of becoming the center around which gathered followers, admirers, friends and enemies. Jacob was, however, no wonder worker in the ordinary acceptation of the term. He had nothing to say to practical or ceremonial magic, and, although most of his friends were drawn from among the alchemists and students of occultism, he did not traffic in retorts, crucibles, or in the effort to extract gold from the baser metals. […] His life was spent in searching for union with God, and the understanding of His laws. [55]

Additional Resources

Articles

- Jacob Boehme at Theosopedia

- Jacob Boehme and the Secret Doctrine by William Q. Judge

- The Life of a Christian Philosopher by Franz Hartmann

- Within, Not Without by Grace F. Knoche

- Jacob Boehme at WisdomWorld.org

- Jacob Boehme Online

- Hall, Manly P. "Mystical Figures of Jakob Boehme, The." Collected Writings of Manly P. Hall Volume 2: Sages and Seers (Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, Inc., 1959), 128-187.

Notes

- ↑ Bach, Jeff. Jacob Boehme. Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe. Brill. Online Publication Date: 11 Feb. 2019. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004393189/BP000014.xml?language=en Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Adolf von Harleß. Jakob Böhme und die Alchymisten.Leipzig, Hinrichsche Buchhandlung,1882. Pag 12

- ↑ Bach, Jeff. Jacob Boehme. Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe. Brill. Online Publication Date: 11 Feb. 2019. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004393189/BP000014.xml?language=en Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ LibriVox. Books in the Public Domain. https://librivox.org/author/10493?primary_key=10493&search_category=author&search_page=1&search_form=get_results Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 5.

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 35.

- ↑ LibriVox. Books in the Public Domain. https://librivox.org/author/10493?primary_key=10493&search_category=author&search_page=1&search_form=get_results Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Bergmann, Carl Josef. Jacob Boehme and the Spread of his Writings in England during the Seventeenth Century. Thesis for the Augustana College, 1910. P. 8. https://archive.org/details/jacobboehmesprea00berg/page/n3/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/21/20.

- ↑ Bach, Jeff. Jacob Boehme. Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe. Brill. Online Publication Date: 11 Feb. 2019. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004393189/BP000014.xml?language=en Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Bergmann, Carl Josef. Jacob Boehme and the Spread of his Writings in England during the Seventeenth Century. Thesis for the Augustana College, 1910. P. 8. https://archive.org/details/jacobboehmesprea00berg/page/n3/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/26/20.

- ↑ Bach, Jeff. Jacob Boehme. Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe. Brill. Online Publication Date: 11 Feb. 2019. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004393189/BP000014.xml?language=en Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Stoudt, John Joseph. Jacob Boehme. His Life and Thought.The Seabury Press, New York. Page 90

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 42.

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 3.

- ↑ Buck, Charles. Theological Dictionary. Joseph Woodward, Philadelphia. 1826. Page 48.

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 7

- ↑ Sinnett, Patience. Jakob Boehme. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510018881740&view=plaintext&seq=329. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Jakob-Boehme-Online-Manuskripts. An Introduction to Jacob Boehme: The Teutonic Theosopher. http://www.passtheword.org/Jacob-Boehme/jb-intro.htm. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Stoudt, John Joseph. Jacob Boehme. His Life and Thought. The Seabury Press, New York. Page 68

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 7

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 1.

- ↑ Bach, Jeff. Jacob Boehme. Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe. Brill. Online Publication Date: 11 Feb. 2019. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004393189/BP000014.xml?language=en Accessed on 5/25/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Doctrines of Jacob Boehme. The God-Taught Philosopher.1910. Chapter I. https://archive.org/details/lifeanddoctrine01hartgoog/page/n16/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Stoudt, John Joseph. Jacob Boehme. His Life and Thought.The Seabury Press, New York. Page 69

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 8

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Doctrines of Jacob Boehme. The God-Taught Philosopher.1910. Chapter I. https://archive.org/details/lifeanddoctrine01hartgoog/page/n16/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 8

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Doctrines of Jacob Boehme. The God-Taught Philosopher.1910. Chapter I. https://archive.org/details/lifeanddoctrine01hartgoog/page/n16/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Reverend William Law. The Life of Jacob Behmen, the Teutonic Theosopher. 1764. http://www.passtheword.org/Jacob-Boehme/life-of-boehme.htm. Accessed on 5/29/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical Figures of Jacob Boehme Horizon. Journal of the Philosophical Research Society. Summer 1948. Page 49. http://manlyhall.org/horizon/horizon-0801-summer-1948.pdf. Accessed on 5/30/20

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical Figures of Jacob Boehme Horizon. Journal of the Philosophical Research Society. Summer 1948. Page 49. http://manlyhall.org/horizon/horizon-0801-summer-1948.pdf. Accessed on 5/30/20

- ↑ Basarab Nicolescu. Science, Meaning, & Evolution. The Cosmology of Jacob Boehme.Parabola Books, New York. 1991. Page 21

- ↑ Basarab Nicolescu. Science, Meaning, & Evolution. The Cosmology of Jacob Boehme.Parabola Books, New York. 1991. Page 83

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Doctrines of Jacob Boehme. The God-Taught Philosopher.1910. Chapter I. https://archive.org/details/lifeanddoctrine01hartgoog/page/n16/mode/2up. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Jakob Boehme. SEX PUNCTA THEOSOPHICA, oder Von Sechs Theosophischen Punkten, hohe & tiefe Gründung. 1620. Printed in 1730.

- ↑ Knoch, Grace. Within, Not Without https://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/modeur/ph-gfk.htm#. Accessed on 5/26/20

- ↑ Boehme, Jacob. The High and Deep Searching of the Threefold Life of Man, Through or according to The Three Principles. Chapter seven, pp. 69-70, London, 1763

- ↑ Knoch, Grace. Within, Not Without https://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/world/modeur/ph-gfk.htm#. Accessed on 5/26/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Life of a Christian Philosopher. https://cdn.website-editor.net/e4d6563c50794969b714ab70457d9761/files/uploaded/LifeofaChristianPhilosopher_FHartmann.pdf. Accessed on 5/28/20

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 14

- ↑ Sinnett, Patience. Jakob Boehme. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510018881740&view=plaintext&seq=332. Accessed on 5/21/20

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Secret of All Ages. Kindle edition. “Jakob Böhme, The Teutonic Philosopher in the chapter “Mystic Christianity.”

- ↑ Hall, Manly. The Mystical Figures of Jacob Boehme Horizon. Journal of the Philosophical Research Society. Summer 1948. Page 49. http://manlyhall.org/horizon/horizon-0801-summer-1948.pdf. Accessed on 5/30/20

- ↑ Weeks, Andrew. Boehme. An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century Philosopher. State University of New York Press, 1991. Page 219.

- ↑ Martensen, Dr. Hans Larsson. Jacob Boehme: His Life and Teaching or Studies in TheosophyHodder and Stoughton, London, 1885. Page 14

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine vol. I, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 494.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Theosophical Glossary (Krotona, CA: Theosophical Publishing House, 1973), 60.

- ↑ William Q. Judge. Jacob Boehme and the Secret Doctrine. Theosophy, November 1896. https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/theos/v11n08p233_jacob-boehme-and-the-secret-doctrine.htm Accessed on 6/2/20

- ↑ Hartmann, Franz. The Doctrines of Jacob Boehme. The God-Taught Philosopher.1910. Page 20. https://archive.org/details/lifeanddoctrine01hartgoog/page/n16/mode/2up. Accessed on 6/2/20

- ↑ Sinnett, Patience. Jakob Boehme. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510018881740&view=plaintext&seq=337. Accessed on 5/21/20