Antaḥkaraṇa

Antaḥkaraṇa (devanāgarī: अन्तःकरण) is a Sanskrit term that means "internal organ". In Hindu philosophy it refers to the totality of the mind, including the thinking faculty, memory, the sense of I-ness, and the discriminating faculty.

In Theosophy the term is used with a special meaning that differs from the Hindu. According to H. P. Blavatsky the antahkarana is an aspect or function of the lower mind that retains its original purity, active whenever there is a spiritual aspiration. It is, figuratively speaking, a "path" or "bridge" that acts as a two-way communication. Through antahkarana the spiritual influence of the higher manas is conveyed to the personality, and all good and noble activity of the lower manas can reach the higher, to be assimilated in Devachan.

General description

H. P. Blavatsky, in The Theosophical Glossary defines it as follows:

Antahkarana (Sk.)., or Antaskarana. The term has various meanings, which differ with every school of philosophy and sect. Thus Sankarâchârya renders the word as “understanding”; others, as “the internal instrument, the Soul, formed by the thinking principle and egoism”; whereas the Occultists explain it as the path or bridge between the Higher and the Lower Manas, the divine Ego, and the personal Soul of man. It serves as a medium of communication between the two, and conveys from the Lower to the Higher Ego all those personal impressions and thoughts of men which can, by their nature, be assimilated and stored by the undying Entity, and be thus made immortal with it, these being the only elements of the evanescent Personality that survive death and time. It thus stands to reason that only that which is noble, spiritual and divine in man can testify in Eternity to his having lived.[1]

In the sevenfold constitution of human beings described in the Theosophical literature, the fifth principle (counting from the physical body upwards) is called manas, commonly translated as "mind". This principle is dual, comprising the higher mind (the spiritual mind, or reincarnating Ego), and the lower mind (the sensual mind, or the psychological ego). According to H. P. Blavatsky, antahkarana is the aspect of the lower mind that does not get entangled with kāma (the animal soul), thus acting as an "imaginary bridge" between the lower and higher egos:

The Antaskarana is therefore that portion of the Lower Manas which is one with the Higher, the essence, that which retains its purity; on it are impressed all good and noble aspirations, and in it are the upward energies of the Lower Manas, the energies and tendencies which become its Devachanic experiences. The whole fate of an incarnation depends on whether this pure essence, Antaskaraṇa, can restrain the Kāma-Manas or not. It is the only salvation. Break this and you become an animal.[2]

The antaḥkaraṇa in Theosophy is not seen as a structural principle but as a temporary function, active when the lower mind aspires towards the higher:

Q. The Antahkarana is the link between the Higher and the Lower Egos; does it correspond to the umbilical cord in projection?

A. No; the umbilical cord joining the astral to the physical body is a real thing. Antahkarana is imaginary, a figure of speech, and is only the bridging over from the Higher to the Lower Manas. Antahkarana only exists when you commence to “throw your thought upwards and downwards.” The Mâyâvi Rûpa, or Mânasic body, has no material connection with the physical body, no umbilical cord.[3]

In order not to confuse the mind of the student with the abstruse difficulties of Indian metaphysics, let him view the lower Manas or Mind, as the personal Ego during the waking state, and as Antaskaraṇa only during those moments when it aspires towards its higher half, and thus becomes the medium of communication between the two. It is for this reason that it is called “Path.”[4]

Antaḥkaraṇa can then be seen as a path that has to be trodden by developing spiritual qualities. A connection has been suggested between the "Portals" in the book The Voice of the Silence and the different "divisions" of the antaḥkaraṇa:

Q. We are told in The Voice of the Silence that we have to become “the path itself,” and in another passage that Antahkarana is that path. Does this mean anything more than that we have to bridge over the gap between the consciousness of the Lower and the Higher Egos?

A. That is all.

Q. We are told that there are seven portals on the Path: is there then a sevenfold division of Antahkarana? Also, is Antahkarana the battlefield?

A. It is the battlefield. There are seven divisions in the Antahkarana. As you pass from each to the next you approach the Higher Manas. When you have bridged the fourth you may consider yourself fortunate.[5]

According to the Law of Correspondences there is a correlation between inner principles and outer organs. Within the human brain, it is said that the pituitary gland or hypophysis is connected to antaḥkaraṇa:

The fourth of these cavities is the Pituitary Body, which corresponds with Manas-Antaskaraṇa, the bridge to the Higher Intelligence; it contains various essences.[6]

According to G. de Purucker

In his Occult Glossary, Gottfried de Purucker uses the word antaḥkaraṇa in a wider sense than H. P. Blavatsky did:

Antaskaraṇa (Sanskrit) Perhaps better spelled as antaḥkaraṇa. A compound word: antar, "interior," "within"; karaṇa, sense organ. Occultists explain this word as the bridge between the higher and lower manas or between the spiritual ego and personal soul of man. Such is H. P. Blavatsky's definition. As a matter of fact there are several antaḥkaraṇas in the human septenary constitution - one for every path or bridge between any two of the several monadic centers in man. Man is a microcosm, and therefore a unified composite, a unity in diversity; and the antaḥkaraṇas are the links of vibrating consiousness-substance uniting these various centers.[7]

According to C. W. Leadbeater

C. W. Leadbeater states that in an ordinary person who makes no effort to use the antahkarana has but little communication with the higher ego:

But though that personality is absolutely part of the ego-- though the only life and power in it are those of the ego-- it nevertheless often forgets those facts, and comes to regard itself as an entirely separate entity, and works down here for its own ends. It has always a line of communication with the ego (often called in our books the antahkarana), but it generally makes no effort to use it. In the case of ordinary people who have never studied these matters, the personality is to all intents and purposes the man, and the ego manifests himself only very rarely and partially.[8]

In these cases, the antahkarana is active mainly during Devachan:

The antahkarana is usually considered in the Theosophical works as the link between the higher self or the divine ego, and the lower self or personal ego. The chitta in that lower self puts it at the mercy of things, so that our life down here may be compared to the experience of a man struggling to swim in a maelstrom. But this will be followed sooner or later after death by a period in the heaven-world. The man has been whirled about; he has seen many things; he has not dwelt upon them, however, with a calm, steady mind, but with kama-manas; therefore he has not understood their significance for the soul. But in the heaven-world the ego can widen out the antahkarana, because all is now calm; no new experiences are to be gathered. The old ones can be quietly turned over and dwelt upon, and their essence taken up, as it were, into the deva ego, as being of interest to him. So, very often, the ego really begins his personal life-cycle with the entry into the heaven-world, and pays a minimum of attention to the personality during its period of collecting materials.

In that case the aspect of mind that is antahkarana (in Madame Blavatsky’s classification) functions but little before the period of the heaven-life.[9]

He adds that a practice that leads to calm the mind clears out the antahkarana and the higher self finds easier to influence the personality during life:

[H]e must bring the positive powers of the higher self down through that channel, by the practice of dharana or concentration, and so make himself entire master of his personality. In other words he must clear out the astral and mental whirlpools.[10]

In Hinduism

In Hindu philosophy, the antahkarana (Skt., often translated as the "internal organ") refers to the psychological apparatus of the individual. In the Vedāntic literature, the antahkaraṇa is organised into four parts:

- Ahamkāra (ego) — the origin to the psychological 'I' associated to the body and its senses.

- Buddhi (intellect) — the principle that is able to discern truth from falsehood and thereby to make wisdom possible.

- Manas (mind) — the faculty of doubt and volition; the lower or instinctive mind, seat of desire and governor of sensory and motor organs.

- Citta (memory) — the part that deals with remembering and forgetting

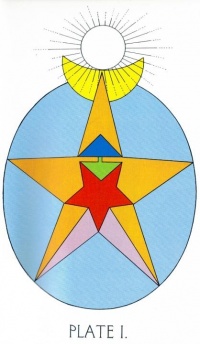

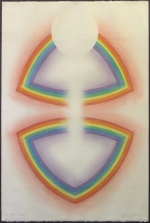

Artistic representations

Theosophical artist Burton Callicott created a beautiful rendition of this concept in his pastel Antahkarana. It hangs by the Meditation Room in the L. W. Rogers Building at the Theosophical Society in America headquarters.

Online resources

Articles

- Antaḥkaraṇa at Theosopedia

Notes

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Theosophical Glossary (Krotona, CA: Theosophical Publishing House, 1918), 22.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings XII, Instruction No. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 710.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Esoteric Writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 428.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings XII, Instruction No. III (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 633.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Esoteric Writings of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 428.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings XII, Instruction No. V (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 697.

- ↑ Gottfried de Purucker, Occult Glossary (Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1996), 5.

- ↑ Charles Webster Leadbeater, The Masters and the Path, (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1992), 173-174.

- ↑ Charles Webster Leadbeater, Talks on the Path of Occultism Volume 2, (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 47.

- ↑ Charles Webster Leadbeater, Talks on the Path of Occultism Volume 2, (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 47.