Cathars

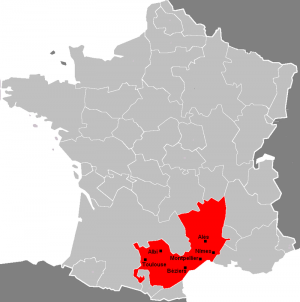

Cathars were a very successful medieval gnostic Christian sect, or heresy from the Catholic perspective, that flourished mainly, but not exclusively, in the southern region of France known as Languedoc, in the tenth through the twelfth centuries. The popularity of the Cathar religion was so great that it practically became the state religion of the Languedoc region at the time. This widespread popularity proved to be a very clear threat to the Catholic Church. Pope Innocent III instigated a campaign to destroy them; this campaign eventually led to the Inquisition which spread across Europe, and, in reality, still exists today. Historians have recognized this war against the pacifist Cathar heresy as the first genocide of Christians by Christians.

Beliefs and their origins

The word Cathar comes from the Greek word katharoi meaning "pure." The Cathars called themselves simply the Good Men. (Incidentally, the world Catholic is also from a Greek root word, katholikos, meaning "universal" or “in general”.) The Cathars were also known as the Albigensian, named for the town of Albi where there was a large settlement. Their beliefs many historians accept spread westward from Bulgaria, Bosnia and Dalmatia. It is believed to have its roots in Manichaeism, Paulicianism, Bolomilism and/or Zoroastrianism. However, recently some researchers are finding evidence to support the idea that the Cathar faith arose locally and the seeds may have been planted, at least in part, by Pythagoras.

When Pythagoras left Greece he studied in Egypt before founding a school in Croton at the toe of the Italian peninsula boot. There also were known to be other Greek settlements in Languedoc along the shore of what is now Marseilles and further westward. Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) is believed to have founded schools in these Greek settlements.

The parallels between the Pythagorean schools and that of the Cathars is noteworthy. They are as follows:

- Believed in reincarnation

- Believed in two supreme opposing powers or gods, or sets of divine or demonic beings, that created the world. They were dualists.

- Teachings were orally transmitted – it was forbidden to write them down

- Accepted both men and women equally into their ranks - gender was not a barrier to rising in the ranks

- Had an inner and outer circle of believers – the inner circle was held to much stricter standards of behavior than the outer circle of the believers known as croyants (believers). The inner circle was privy to the higher secrets unavailable to the outer circle of followers.

- Personal property of all kinds was relinquished to the church. This was expected of the inner circle but not the outer circle.

Cathars did believe in the teachings of Jesus in their purest form, which they felt had been corrupted by the Catholic Church. They did not recognize the authority of the Pope but maintained their own loose structure of a church with bishops at varies levels and overseeing different territories. As an oral tradition, the Cathars had few written books they considered sacred but there were a few- besides the New Testament, The Gospel of the Secret Supper, or John's Interrogation and The Book of the Two Principles. There has been confusion concerning Cathar attitude toward John the Evangelist and John the Baptist. Strangely Cathars did not look favorably upon John the Baptist, describing him as a "demon."[1] They believed Jesus passed on his secret teachings to his inner circle which included young Saint John.

Cathars found the Catholic practice of worshipping a crucifix, an effigy of their savior dying of a cross, abhorrent. In fact, some Cathars believed Jesus was never crucified or that he had survived the crucifixion and had come to southern France to escape further persecution. Why France? It has been suggested that during the so-called “lost years” of Jesus he spent his time in Egypt (just at Pythagoras did) learning the esoteric secrets he revealed to his inner circle and preached in his ministry.

In the Languedoc region there is a tradition that says Mary Magdelaine also came to France after the possible crucifixion and brought her child, whose father was Jesus, a little girl named Sara. Mary preached and was worshipped openly in the region in the Cult of Mary Magdelaine. Mary taught and brought up her child who eventually married into a line of French kings called the Merovingians; this is how the bloodline of Jesus was believed to have continued. True or not, the Cathars accepted that Mary Magdalene was either the wife or concubine of Jesus. As the Cathars did not approve of marriage or sexual intercourse, it seems unlikely they would have invented this “distasteful” relationship so it is believed to have come from an older accepted tradition.

As Gnostics, there was no doubt of their opposition to the teachings of the Holy Roman Church. Gnostics need no intermediary between them and the divine. Of course, this made priests completely unnecessary and the whole structure of the church with its excessive rituals, rules and ‘salvation for price’ would collapse.

The Good Men were pacifists, non-violent to the point where they would not defend themselves against attack, consequently, non-Cathar sympathizers, would voluntarily act as body guards for the Cathars against the Catholic crusaders. The nobles of the region treated the Cathars with great respect and deference. Cathars inspired the admiration and loyalty of non-Cathars simply by the example of how they lived their lives, emulating the simplicity and kindness of Jesus. They were recognized, not only by the ordinary citizens as selfless, principled, completely honorable people but the Catholic Church itself had to admit to the total lack of corruption in the Cathar ranks. By comparison the Catholic clergy were a shambles of incompetence, hypocrisy and debauchery which disgusted the ordinary people drawing more and more to the Cathar church. And monetary contributions were generous to the Good Men. The Cathar Church grew very rich, using it resources to help the poor, build hospitals and schools, while the Catholic Church’s coffers were dwindling.

The Cathars believed the material world was hell, the only hell. It was created by an evil God, a demi-urge (Rex Mundi) who existed in opposition to the good god of pure spirit. They believed human beings must reincarnate repeatedly until their souls were purified by living a life of simplicity and virtue so that eventually they would be reunited with the good god after death. Therefore, there was no hell after death, as the Catholics taught, for those who did not obey the Catholic rules. This “no-hell” facet of their teachings was a very attractive draw for the people living in constant fear of Catholic exploitation.

Reincarnation was also part of the Cathar beliefs. Zoé Oldenbourg, Cathar historian and author of Massacre at Montsegur, compared the Cathars to "Western Buddhists" noting that the Cathar doctrine of resurrection, as taught by Jesus, was comparable to the Buddhist doctrine of reincarnation. Until a croyant was willing to renounce the material self completely, they would be condemned to reincarnate and live again and again in the corrupt world of matter. Cathars, however, did not accept the Buddhist doctrine of karma, where the result of actions in one life were carried over into the next.

Another correlation with the Buddhist faith was the Cathar emphasis on contemplation and meditation. A perfecti spent many hours a day in prayer and meditation. "They were spiritualist without being in the least inclined to witchcraft, sorcery and magic."[2] The perfecti expressed psychic abilities and amazing healing powers, much the way Jesus did. The Catholics seized on these powers as a witchcraft and a reason for persecution. Apparently, healing was something reserved only for their savior, Jesus, and not for the common man. But the Cathars taught that the powers they developed through dedicated meditation and prayer were available to every human being, just as Jesus had taught twelve centuries before.

The only sacrament practiced by the Cathars was called the Consolamentum which was administered upon becoming a perfecti and upon the death bed. This was a very austere and mysterious ritual about which little is known. But whether administered upon becoming a perfecti or at the approach of death "the idea was that the compulsion of the flesh was rejected and the aspirant devoted, or relinquished, himself to the life of spirit."[3] The strictest austerity was expected after the Consolamentum was administered which is why, other than becoming a perfecti, the right was administered at death. The inclusion of women in the faith of the Cathars particularly upset the Catholic officials. Women could join the church and become “perfecti’ – the Cathar equivalent of a Catholic priest. The perfecti travelled in pairs and preached their gospel in forests, caves, private homes – where ever they were welcome. The Cathars did have an administrative structure with bishops of different ranks and territory but they preferred no structural church. The lived a simple modest life travelling, spreading the word, helping the poor and healing the sick.

Sexual intercourse was forbidden because it could result in another soul being born and thus trapped in the evil world of matter. The perfecti were expected to adhere to this prohibition but the ordinary croyants were not. Sex was not considered an unforgiveable sin. In fact, many men and women who had raised a family decided in later life to give their earthly belongings to the Cathar church and become perfecti. One of the most famous women perfecti was Esclarmonde de Foix, the daughter of the Count of Foix. After raising five children she was widowed in 1200 when she joined the Cathar church and became prominent perfecti. She is responsible for building schools for girls and several hospitals in the region.

At the time the Cathars flourished the whole Languedoc region was enjoying a sort of revitalization, and atmosphere that existed nowhere else in Europe. The love of knowledge, personal freedom, music, schools of mysticism and philosophy all thrived. This was the time of troubadours and courtly love. An eagerness for new and foreign goods, as well as, new and foreign ideas was the prevailing attitude. An unprecedented enthusiasm for creativity and artistic expression distinguished the Languedoc. Stunning cathedrals were constructed. A rich trade route from Spain to the East brought prosperity to the area. The Languedoc and its landholders had grown very wealthy.

The End

The first mention of the Cathars in history is in 1143. The last known record of the Cathars is in 1325. But many researchers insist the Languedoc region of France is still saturated with the memory of the Bonne Hommes (the Good Men). A strange melancholy permeates the sites where the Cathars met their end. This is the lasting power of martyrdom, though the Cathars did not seek to be martyrs. True martyrdom is not deliberate.

After years of trying to stop the spread of Catharism and bring straying Catholics back into the fold by preaching, open debates and putting pressure on local authorities to crack down the Cathars the Pope finally lost patience. He excommunicated Count Raymond IV of Toulouse for failing to take action against the Cathars. On January 14, 1208 a papal legate, Peter de Castlenau, was to deliver to the Count the news of his excommunication. The legate was murdered by a vassal of Count Raymond. Finally, the Pope had a “legitimate” reason to call for war. Two months after the murder the Pope issued a call to arms.

The Pope called for “a crusade against the Cathars considered a far greater danger to Christianity than all the armies of Islam.”[4] The Christian crusaders turned their attention from the Infidels in the Middle East to their own backyard focusing all their fury on fellow European Christians. Those taking part in this crusade were granted absolution for all sins – past, present and future. They were essentially given carte blanche to seize the property of any heretic, noble or peasant, and also implied consent to steal, murder, rape, plunder and pillage. The result was “a war which even by medieval standards was shockingly violent.”[5]

It is interesting to note that the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller, both supposedly on the side of the Pope, never played a role in the Cathar massacres ordered by the Church. No record is found of how the Pope reacted to their obvious absence. The Languedoc region was known to have by far the greatest concentration of Templar families, so either because of family bonds or acceptance of the Cathar creed the Templars were not only tolerant but protective of the Cathars. Some historians say the Templars gave their treasures to the Cathars for safe keeping. Some rumors even claimed the Templar Treasure included the Holy Grail. No matter what the treasure may have been there was some sort of understanding between the Cathars and the Knights.

In July of 1209 the papal army arrived at Beziers and demanded the citizens either hand over the 222 Cathars living within the city walls or the Catholics living there should leave the city so the Cathars left behind within the city could be dealt with. This demand was made on pain of excommunication but the townspeople refused to surrender the Cathars. According to reports, the townspeople took an oath to defend the Cathars.

The crusaders marched into the city and hacked to death every man, woman and child and then torched the city. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people were butchered in less than a day. It was at this famous siege that one of the crusader’s lieutenants, knowing the city was primarily Catholic, asked the commander, Arnauld Aimery, how to tell the difference between the heretics and the townspeople. Aimery replied “Kill them all. God will know his own.”[6] Beziers was attacked on St. Mary Magdalaine’s Day – a crusader by the name Pierre des Vaux de Cremat made comment on the deliberate timing of the attack “….just cause that these disgusting dogs were taken and massacred during the feast of the one that they had insulted.”[7] The insult of course being that the Cathars believed Mary Magdelaine to be the wife of Jesus.

The walled city of Carcassonne was next to be sieged. Having heard of the atrocities at Beziers the horrified city surrendered without a fight. All citizens were required to abandon their homes and possessions immediately as spoils to the invading army and Simon De Montfort was awarded all feudal rights, property and titles of Viscount Trencavel, the Lord of Carcassonne.

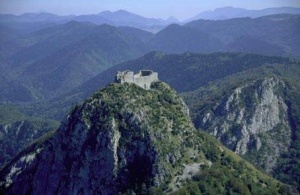

Beziers and Carcassonne were the opening acts of thirty 30 years of incredible brutality. More than thirty-five Cathar strongholds, seemingly impenetrable fortresses like the one pictured here (The Château de Puilaurens) were conquered by the Crusaders, such was the fury and determination of the Catholic army. Simon de Montfort especially distinguished himself by his cruelty, ordering public burnings of hundreds of perfecti at a time (both men and women) without so much as a mock trial. Bestial mutilations and obscene tortures horrified the population. An estimated one million people, Cathar, Catholic, and Jew died in the Albigensian crusade.

The final blow to the Cathars came with the fall of formidable and, for the Cathars, very symbolic stronghold at Montsegur in 1244. Montsegur castle sits atop a very steep, very sharp, craggy outcrop of rock at 3,900 feet in altitude located about 50 miles southwest of Carcassonne. The word Montsegur translates as Safe Mountain. This fortress is believed to be the original of the Grail Castle in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s grail romance Parzival (circa 1200–1210) which in the story was called Monsalvat, which also translates at Safe Mountain.

The Siege of Montsegur

The taking of Montsegur (pictured above) was a prolonged exercise in endurance; it has often been compared to the tragedy at Masada. Surrounded and bombarded for ten months, 150 Cathar protectors defended 205 Cathars and about 150 civilians against and army of 10,000 troops from the seneschal of Carcassonne and the archbishop of Narbonne. Starvation, lack of water and dwindling supplies meant eventual death but a strange thing happened. The Cathars surrendered on March 2, 1244 but instead of the Pope’s army immediately swarming the stronghold a two-week truce was granted to the Cathars. During this time the perfecti took the final Consolamentum in preparation for this death. Most of their defenders also chose to take the Consolamentum and to die with the Cathar perfecti they had protected. But it is also reported by one who defended the fortress, Raymond de Pereille, when he was later subjected to the Inquisition that during the two week truce, three or four perfecti had left the castle by a secret route, lowered themselves down the treacherous precipice of the Montsegur, escaped pasted the enemy with the intent of recovering a treasure the Cathars that had buried in a nearby forest in the weeks prior to the surrender. What that treasure was has never been discovered.

At the end of the truce 205 Cathar perfecti walked calmly into a huge fire prepared for them at the foot of the mountain and met their deaths calmly and stoically, no need for being tied to stake. It has been suggested that in preparing for their deaths by such a horrible torture the Cathars had put themselves into a trance and thus maintained a perfect serenity as they walked into the flames and burned to death.

Today on this spot where the burning took place a memorial stands to commemorate the victims. It reads, in Occitan - “The Cathars, martyrs of pure Christian love. 16 March 1244” In the aftermath of the fall of Montsegur Catharism continued in Languedoc for a while but oppression from the Inquisition sent many follows to other lands, like Italy or Spain, where there was more tolerance of the Cathar faith. Montsegur was a psychic blow as well as a physical one.

The Catholic Church went on to massacre hundreds of thousands of people, heretics of any sect, in the Inquisition that spread all over Europe.

Legacy

The Cathars had a powerful and lasting mystique that is difficult to comprehend and since most of our knowledge of them comes from their conquerors we are not likely to know the truth of what it was, by conventional mean anyway. Why would so many who were not perfecti or even croyants choose to die with the Cathars when they could easily have escaped? The Catholic Church offered forgiveness and life to the Cathars themselves if only they would renounce their faith. The Cathar defenders, the ordinary people of Beziers, and in many other smaller incidences – non-Cathars chose death beside the Cathars.

Certainly the Catholic Church was offended by the Cathar belief system but the prosperity of the Cathars, their supporters and the entire Languedoc region was certainly a strong incentive for the Catholic Church to seize the wealth of the area. The property of the Cathar Church and the non-Cathar supporters were divided up among the conquering French from the north. Politically, the Languedoc became part of France expanding its southern border to the Mediterranean Sea where it is today and the French king, of course, expanded his kingdom.

Many historians have noted that if the civilization that existed in the Languedoc at the time of the Cathars, the atmosphere of tolerance, love of learning, curiosity and eager exchange of ideas with foreign lands, the construction of magnificent cathedrals, all of this - had not been destroyed by the Albigensian Crusade all of Europe might have enjoyed the Renaissance 300 years earlier and all of humanity might be 300 years more advanced than it is now.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Gilbert, Adrian. Magi: The Quest for a Secret Tradition. London: Bloomsbury, 1996. Print.

Guirdham, Arthur. The Great Heresy. St Helier: Neville Spearman (Jersey) ;, 1977. Print.

Guirdham, Arthur. The Cathars & Reincarnation. London: Spearman, 1970. Print.

Hancock, Graham, and Robert Bauval. Talisman: Sacred Cities, Secret Faith. London: Michael Joseph, 2004. Print.

Murphy, Tim, and Marilyn Hopkins. Custodians of Truth: The Continuance of Rex Deus. Boston, MA: Weiser, 2005. Print.

Oldenbourg, Zoe. Massacre at Montségur; a History of the Albigensian Crusade. New York: Pantheon, 1962. Print.

Picknett, Lynn, and Clive Prince. The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1998. Print.

Simmans, Graham. Jesus after the Crucifixion: From Jerusalem to Rennes-le-Château. Rochester, Vt.: Bear, 2007. Print. Smith, Morton. Jesus the Magician. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1978. Print.

Notes

- ↑ Picknett, Lynn, and Clive Prince. The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1998. Print. P. 95.

- ↑ Guirdham, Arthur. The Great Heresy. St Helier: Neville Spearman (Jersey) ;, 1977. Print P. 102

- ↑ Guirdham, Arthur. The Great Heresy. St Helier: Neville Spearman (Jersey) ;, 1977. Print. P. 42

- ↑ Murphy, Tim, and Marilyn Hopkins. Custodians of Truth: The Continuance of Rex Deus. Boston, MA: Weiser, 2005. Print. P. 168

- ↑ Simmans, Graham. Jesus after the Crucifixion: From Jerusalem to Rennes-le-Château. Rochester, Vt.: Bear, 2007. Print. P. 236

- ↑ Picknett, Lynn, and Clive Prince. The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. New York, N.Y.: Simon & Schuster, 1998. Print. P. 88

- ↑ Murphy, Tim, and Marilyn Hopkins. Custodians of Truth: The Continuance of Rex Deus. Boston, MA: Weiser, 2005. Print. P. 170