Maud Hoffman: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

[[H. N. Stokes]], in his [[The O. E. Library Critic (periodical)|''The O. E. Library Critic'']], wrote that the president of the [[Theosophical Society (Adyar)|Theosophical Society based in Adyar]], [[Annie Besant]], ejected Miss Hoffman from the [[Esoteric Section]] for releasing the Mahatma Letters to the public against the wishes of the Mahatmas.<ref>H. N. Stokes, "Leadbeater Whacks Barker" ''O. E. Library Critic'' 21 no.5 (December, 1931): 11.</ref> However, Sinnett himself saw no objection in publishing the letters, and was supported in this by [[Gottfried de Purucker]] and others.<ref>W. Emmett Small and Helen Todd, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" ''Eclectic Theosophist'' no.20 (January 15, 1974): 4.</ref> Many of the letters had previously been published in books and periodicals. Miss Hoffman formed the Mahatma Letters Trust, and turned over responsibility for future editions to [[Christmas Humphreys]] and [[Elsie Benjamin]]. | [[H. N. Stokes]], in his [[The O. E. Library Critic (periodical)|''The O. E. Library Critic'']], wrote that the president of the [[Theosophical Society (Adyar)|Theosophical Society based in Adyar]], [[Annie Besant]], ejected Miss Hoffman from the [[Esoteric Section]] for releasing the Mahatma Letters to the public against the wishes of the Mahatmas.<ref>H. N. Stokes, "Leadbeater Whacks Barker" ''O. E. Library Critic'' 21 no.5 (December, 1931): 11.</ref> However, Sinnett himself saw no objection in publishing the letters, and was supported in this by [[Gottfried de Purucker]] and others.<ref>W. Emmett Small and Helen Todd, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" ''Eclectic Theosophist'' no.20 (January 15, 1974): 4.</ref> Many of the letters had previously been published in books and periodicals. Miss Hoffman formed the '''[[Mahatma Letters Trust]]''', and turned over responsibility for future editions to [[Christmas Humphreys]] and [[Elsie Benjamin]]. | ||

In 1931, Miss Hoffman was a participant in the '''Centennial Conference''' in London held to honor the birth of [[Theosophical Society]] founder [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky]]. The conference was an attempt proposed by [[Gottfried de Purucker]] to bridge gaps in the fractured [[Theosophical Movement]] in order to restore a sense of brotherhood and unity. Miss Hoffman was invited as an independent Theosophist of England.<ref>Anonymous, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" ''The Eclectic Theosophist'' no.20 (Jan 15, 1974): 1.</ref> | In 1931, Miss Hoffman was a participant in the '''Centennial Conference''' in London held to honor the birth of [[Theosophical Society]] founder [[Helena Petrovna Blavatsky]]. The conference was an attempt proposed by [[Gottfried de Purucker]] to bridge gaps in the fractured [[Theosophical Movement]] in order to restore a sense of brotherhood and unity. Miss Hoffman was invited as an independent Theosophist of England.<ref>Anonymous, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" ''The Eclectic Theosophist'' no.20 (Jan 15, 1974): 1.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 20:11, 19 December 2023

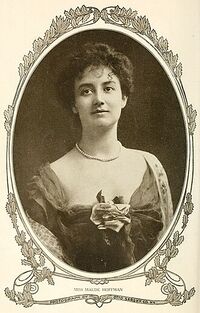

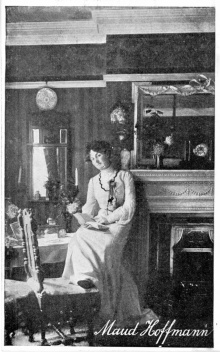

Maud Hoffman (1869-1953) was an American Theosophist and actress who was heir to the estate of A. P. Sinnett. She entrusted A. Trevor Barker with the task of publishing The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett and The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett, both based on correspondence from the Sinnett estate.

Early life

Maud was born as the daughter of John T. Plummer and Martha Plummer in Indianapolis, Indiana in December 4, 1869 or 1870.[1] John was a letter carrier. By 1880, Martha and Maud were living in Kansas City. Martha was married to carpenter W. T. Hoffman, who had a son Harry two years older than Maud. The family moved to Corvallis, Oregon, where Maud received most of her early schooling.

At the age of 17, Maud enrolled in a two-year course at a California finishing school, followed by a season in New York studying elocution. She taught for a year in a public school in Corvallis, and then moved on to become an instructor of elocution in St. Helen's Hall, Portland.[2]

Theatrical career

Maud was not trained as an actress before she took on her first role, but somehow she was cast as Juliet and made a noteworthy debut in Boston:

Her opening night drew the largest and most fashionable audience that ever filled the theater. For the first time in its career, every critic in town was there. The audience was quick to recognize the value of her work and quick to respond to her acting, and she won a decided triumph. That a debutante should draw a crowded house for seven consecutive performances, in a Shakespearean play, is indeed remarkable. The fact of her having never performed before even as an amateur, and having had only two months real dramatic training, makes her success all the more astonishing.[3]

She applied to E. S. Willard for understudy work, and joined his company for the season of 1891-1892, and held the role of Player Queen in Hamlet. Later she worked with the Augustin Daly company.[4] She also performed as Calpurnia in Julius Caesar, and had roles in Great Ruby, Dandy Dick, Cipher Code, New England Folks, and Colorado.[5]

American newspapers continued to follow her career after she moved to London around 1895 to join Wilson Barrett's theatre troupe, where she took on roles as Juliet, Ophelia, Desdemona, and Berenice in The Sign of the Cross. News agencies like the Associated Press covered her activities, and even small regional papers, such as the Logansport Pharos-Tribune in Indiana, published substantial stories about her.

In 1911, the New York Times wrote that a performance in London's famous Royal Court Theatre of a new comedy in three acts entitled Married by Degrees, was "noteworthy, chiefly because it provided the medium for an American actress, Miss Maud Hoffman, to make a distinctly successful appearance before a British audience."[6] This play was written by A. P. Sinnett, and her success probably had a role in cementing their friendship.

Feminist activities

Miss Hoffman participated in the Actresses' Franchise League, an organization supporting women's suffrage. She was a marshal in the Great Procession of Women, a huge demonstration that took place in London on June 17, 1911.

Between 40,000 and 60,000 women from over forty suffrage societies walked five abreast through London from Temple to the Albert Hall. The AFL was the thirteenth society in the procession, and the position of the organisation is an indication of their usefulness to the movement as figures of interest for the general public as well as the press. [7]

The AFL women were dressed elegantly in the pink and green colors of the suffragist movement, carrying flowers and following strict guidelines on dress and deportment.

Theosophical Society activities

Maud Hoffmann joined Theosophical Society's H.P.B. Lodge in London on January 6, 1909.[8] She seems to have been active in her lodge, lecturing and training lecturers.[9] London Theosophists were certainly very important in her life; she shared rooms with Mabel Collins and was a dear friend of Alfred Percy Sinnett.

Mr. Jinarājadāsa wrote of her involvement with A. P. Sinnett and the Mahatma Letters that were published by her agency in 1923:

Mr. Sinnett had a devoted friend, Miss Maud Hoffman, almost like a daughter, who tended him in his last years, and he made her his legatee and executrix, and so the Letters came into her possession. Miss Hoffman then asked Mr. A. Trevor Barker to do the best that he could with them, and Mr. Barker published them as the work The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett.[10]

H. N. Stokes, in his The O. E. Library Critic, wrote that the president of the Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Annie Besant, ejected Miss Hoffman from the Esoteric Section for releasing the Mahatma Letters to the public against the wishes of the Mahatmas.[11] However, Sinnett himself saw no objection in publishing the letters, and was supported in this by Gottfried de Purucker and others.[12] Many of the letters had previously been published in books and periodicals. Miss Hoffman formed the Mahatma Letters Trust, and turned over responsibility for future editions to Christmas Humphreys and Elsie Benjamin.

In 1931, Miss Hoffman was a participant in the Centennial Conference in London held to honor the birth of Theosophical Society founder Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. The conference was an attempt proposed by Gottfried de Purucker to bridge gaps in the fractured Theosophical Movement in order to restore a sense of brotherhood and unity. Miss Hoffman was invited as an independent Theosophist of England.[13]

War work

Miss Hoffman was living near Hastings in England during the First World War, having retired from acting. She was interviewed for a Portland, Oregon newspaper:

We all do various war jobs. I have been engaged with the sending of reading matter to the front. I am doing a good deal of literary work lately. But nothing in the way of books can be sent abroad now. Many of my friends are doing special constable work. Everybody is doing something.[14]

She went on to offer assistance to Oregon soldiers who were traveling through England or who were recovering from injuries.

Connection to Gurdjieff

In October, 1921, P. D. Ouspensky was in London lecturing on the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff. Maud Hoffman and A. Trevor Barker became students of Ouspensky, until they heard Gurdjieff himself speaking at the Theosophical Society's rooms on February 13, 1922. At that point they became pupils of Gurdjieff, along with their friends Dr. Maurice Nicoll and Dr. James Young.[15]

They [Hoffman and Barker] went with him [Gurdjieff] to Fountainebleau in France to help prepare his occult school, known as the Prieuré, to receive students... While studying at the Prieuré, these two pupils of Gurdjieff were working on the transcription, editing, compilation, and publication of what became known as the Mahatma Letters.[16]

After the letters were published in December, 1923, Miss Hoffman "continued as a residential pupil into 1924."[17]

Writings

Miss Hoffman adapted the popular Mabel Collins book Idyll of the White Lotus into a play called Sensa, a Mystery Play in Three Acts.[18]

Additional resources

- Sensa, a Mystery Play in Three Acts. Covina, California, 1950. Made available online by Theosophy Northwest.

- The Mahatma Letters: Some Notes On Maud Hoffman by Marc Demarest in Chasing Down Emma Blogspot. Posted June 24, 2015.

Notes

- ↑ Consular Registration Application, 1917.

- ↑ "Miss Maud Hoffman, a Webfoot [Oregonian] Juliet," The Oregonian (June 4, 1893): 13.

- ↑ "Miss Maud Hoffman, a Webfoot [Oregonian] Juliet," The Oregonian (June 4, 1893): 13.

- ↑ Untitled column, Logansport Pharos-Tribune (November 16, 1897): 18.

- ↑ "Miss Hoffman is a Coming Star" Philadelphia Inquirer no.148 (February 15, 1903): 9,

- ↑ "American Actress Scores in London; Maud Hoffman Makes Success of Difficult Role in New Comedy," Married by Degrees, New York Times (September 17, 1911): Section C, page 4.

- ↑ Naomi Paxton, Stage rights!: The Actresses’ Franchise League, activism and politics 1908–58 Manchester University Press, 2018.

- ↑ Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 3, entry 38033 (website file: 3D/37).

- ↑ "Lecturers' Classes" The Vahan 22 no.8 (March, 1913): 185.

- ↑ C. Jinarajadasa, "On the Watchtower" The Theosophist 72 no.9 (June, 1951): 146-147.

- ↑ H. N. Stokes, "Leadbeater Whacks Barker" O. E. Library Critic 21 no.5 (December, 1931): 11.

- ↑ W. Emmett Small and Helen Todd, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" Eclectic Theosophist no.20 (January 15, 1974): 4.

- ↑ Anonymous, "In the Future - a Spiritual Brotherhood" The Eclectic Theosophist no.20 (Jan 15, 1974): 1.

- ↑ "Ex-Oregon Woman, Retired from Stage, Does War Work" The Oregon Sunday Journal (October 28, 1917): 1.

- ↑ Seymour B. Ginsburg, "A Teacher of Dancing: The Mahatma Letters and Gurdjieff" The Quest 103 no.2 (April, 2015): 59.

- ↑ Seymour B. Ginsburg, "The Task of Becoming Sixth-Race Man" The Quest 99 no.4 *October, 2011): 141.

- ↑ Seymour B. Ginsburg, "A Teacher of Dancing: The Mahatma Letters and Gurdjieff" The Quest 103 no.2 (April, 2015): 58.

- ↑ Published in 1950 by Theosophical University Press in Covina, California. It is available online at Theosophy Northwest [1]