Charlotte Despard: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Charlotte Despard.jpg|right| | [[File:Charlotte Despard.jpg|right|180px|thumb|Charlotte Despard]] | ||

[[File:WSPU meeting.jpg|right|300px|thumb|WSPU meeting]] | |||

'''Charlotte Despard''' was an Anglo-Irish writer and social activist. | '''Charlotte Despard''' was an Anglo-Irish writer and social activist. | ||

| Line 5: | Line 6: | ||

Born Charlotte French, 15 June 1844, third daughter of five and one son of Captain John Tracey William French (d. 1854) and Margaret (d. c.1865). Charlotte grew up lacking a formal education as was common for girls in Victorian England, a cultural habit she lamented. At approximately 19 she attended a finishing school in London. By this point her father had passed and her mother suffered a mental breakdown requiring institutionalization. | Born Charlotte French, 15 June 1844, third daughter of five and one son of Captain John Tracey William French (d. 1854) and Margaret (d. c.1865). Charlotte grew up lacking a formal education as was common for girls in Victorian England, a cultural habit she lamented. At approximately 19 she attended a finishing school in London. By this point her father had passed and her mother suffered a mental breakdown requiring institutionalization. | ||

Charlotte married on 20 December 1870. Her husband, Maximilian Carden Despard (1839–1890), was a wealthy Anglo-Irish businessman and social radical who encouraged Charlotte to write. She wrote ten novels, seven of which were published. One of the earliest was '' | Charlotte married on 20 December 1870. Her husband, Maximilian Carden Despard (1839–1890), was a wealthy Anglo-Irish businessman and social radical who encouraged Charlotte to write. She wrote ten novels, seven of which were published. One of the earliest was ''Chaste as Ice, Pure as Snow'' (1874). One of the most famous was ''The Rajah's Heir, a novel'' (1890). Charlotte and her husband traveled Europe and India extensively. Yet, they never had children. She became a widow in 1890 when her husband was lost at sea. Losing her husband seems to have opened up possibilities for Despard for just after mourning for a few months she relocated to London slums and began working earnestly to bring relief and education to the poor. | ||

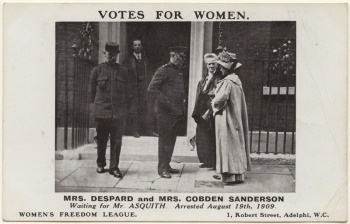

[[File:Despard and Cobden-Sanderson at No10.jpg|right| | [[File:Despard and Cobden-Sanderson at No10.jpg|right|350px|thumb|Waiting for Prime Minister at No. 10 Downing St. 1909]] | ||

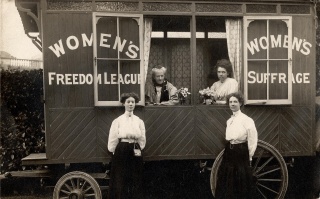

[[File:Charlotte Despard and Allison Neilans in WFL caravan 1908.jpg|320px|right|thumb|Charlotte Despard and Allison Neilans in 1908 WFL caravan tour.]] | |||

== Political and social activism == | == Political and social activism == | ||

Despard’s earliest effort at social reform was establishing one of the first child welfare centers on 2 Currie St., Nine Elms, London, a location she maintained for almost two decades, a working men’s club, became a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth, London, in 1894, and joined the Labour Party. She was known to wear simple black clothing and sandals. During this time she also became a suffragette joining the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). | Despard’s earliest effort at social reform was establishing one of the first child welfare centers on 2 Currie St., Nine Elms, London, a location she maintained for almost two decades, a working men’s club, became a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth, London, in 1894, and joined the Labour Party. She was known to wear simple black clothing and sandals. During this time she also became a suffragette joining the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She and other members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) founded the '''Women's Freedom League''': | ||

<blockquote> | |||

it went on to become one of the largest British suffragette organizations gaining a membership of 4,000 soon after its founding in 1907. While the WFL wasn’t violent, it was militant: Led by vegetarian Charlotte Despard, members refused to pay taxes, citing lack of representation.<ref>Ann Ewbank, [https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-did-british-suffragettes-eat?utm_source=Atlas+Obscura+Daily+Newsletter&utm_campaign=dec3540e22-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_07_09&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f36db9c480-dec3540e22-63009869&ct=t(EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_7_9_2018)&mc_cid=dec3540e22&mc_eid=01959507a7 "How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement"] at ''Atlas Obcura'' July 03, 2018.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

By 1916, the Women's Freedom League had established the vegetarian '''Minerva Café''', "which was part of a larger facility of meeting rooms and lodging. A surprising number of British suffragettes were vegetarians, and had been even before campaigning for the vote... While fighting for the right to vote, many passionately argued against vivisection, wearing fur coats and stuffed-bird hats, and eating meat."<ref>Ann Ewbank, [https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-did-british-suffragettes-eat?utm_source=Atlas+Obscura+Daily+Newsletter&utm_campaign=dec3540e22-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_07_09&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_f36db9c480-dec3540e22-63009869&ct=t(EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_7_9_2018)&mc_cid=dec3540e22&mc_eid=01959507a7 "How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement"] at ''Atlas Obcura'' July 03, 2018.</ref> The café was home to several feminist groups, as well as anti-war activists, anarchists, socialists, and naturists.<ref>Nick Heath, [https://libcom.org/history/minerva-caf%C3%A9 The Minerva Café"] at Libcom.org. Jan 1 2017. </ref> | |||

[[File:Charlotte Despard at produce stall 1930s.jpg|350px|right|thumb|Charlotte Despard and Emmeline Pethick Lawrence at a produce stall 1930s.]] | |||

== Theosophical Society and other occult organizational connections == | == Theosophical Society and other occult organizational connections == | ||

Despard, embracing her Irish heritage, converted to Roman Catholicism at the end of the 1890s and also joined the Theosophical Society | Despard, embracing her Irish heritage, converted to Roman Catholicism at the end of the 1890s and also joined the Theosophical Society on April 4, 1899.<ref>Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at [http://tsmembers.org/ http://tsmembers.org/]. See book 2, entry 16690 (website file: 2A/18).</ref>. In the February 1917 issue of [[The Herald of the Star (periodical)|''The Herald of the Star'']], Theosophist John Scurr calls Despard the [http://resources.theosophical.org/pdf/Authors/Scurr/Scurr_Beneficent_Fairy_of_Nine_Elms.pdf “Beneficent Fairy of Nine Elms,”] describing how she helped women save money, facilitated by the Married Women's Property Act of 1882. Prior to the act, the husbands owned the earnings of their wives and often took it for alcohol and other selfish desires. The act let wives designate Despard as the trustee of the funds, protecting their earnings from their husbands. Similarly, Scurr discusses how Despard cared for children injured through labor or play. “It was a lesson to anyone who is leading a soft, comfortable existence to see how children of seven or eight bore unflinchingly and with a brave face the smarting pain when ointments and lotions were applied.” He also describes her suffrage efforts and other work for the rights of women and the working poor. Seeming to fully embody Theosophy’s core principle of selflessness, Scurr ends writing of Despard, “Love and service are the dominant passions of her life. When the history of this time is written no one will occupy a higher place than the beneficent fairy of Nine Elms— Charlotte Despard.”<ref>Scurr, John. “The Beneficent Fairy of Nine Elms.” The Herald of the Star 6, no. 2 (February 1917): 107–9.</ref> | ||

Despard also maintained an interest in other esoteric and occult organizations in addition to the Theosophical Society. ''Light, A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research'', notes that Despard gave a speech about “The New Womanhood” to The London Spiritualist Alliance, and organization which other theosophists participate, including A.P. Sinnett. Similarly, she gave the lecture, “The Spiritual Ideal of Womanhood” at the Ninth National Conference of Spiritualists, 2 July, 1911. And the June 1905 issue of the ''Journal of the Society for Psychical Research'' lists Despard as a new member. | Other sources mention Despard's work under Miss Eglantyne Jebb, who founded Save the Children Fund in 1919.<ref>L. Haden Guest letter to George Arundale, "On the Watch-Tower" ''The Theosophist'' 41 no.8 (May, 1920): 107.</ref><ref>[https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/blogs/2023/our-founder-eglantyne-jebb Our Founder, Eglantyne Jebb] at Save the Children website.]</ref> | ||

[[File:Despard Theosophy front cover.jpg|right| | |||

Her most well-known Theosophical publication is her ''Theosophy and the | Despard also maintained an interest in other esoteric and occult organizations in addition to the Theosophical Society. ''Light, A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research'', notes that Despard gave a speech about “The New Womanhood” to The London Spiritualist Alliance, and organization which other theosophists participate, including [[Alfred Percy Sinnett|A.P. Sinnett]]. Similarly, she gave the lecture, “The Spiritual Ideal of Womanhood” at the Ninth National Conference of Spiritualists, 2 July, 1911. And the June 1905 issue of the ''Journal of the Society for Psychical Research'' lists Despard as a new member. | ||

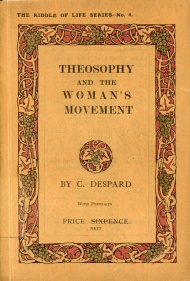

[[File:Despard Theosophy front cover.jpg|right|190px|thumb| | |||

'''[https://archive.org/details/DespardTheosophyAndTheWomansMovement ''Theosophy and the Woman's Movement'']''']] | |||

Her most well-known Theosophical publication is her [https://archive.org/details/DespardTheosophyAndTheWomansMovement ''Theosophy and the Woman's Movement''] (1913). | |||

== Writings == | == Writings == | ||

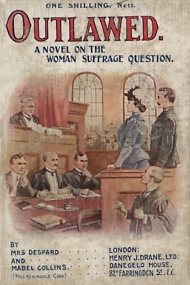

[[File:Outlawed-Book-Cover.jpg|right| | [[File:Outlawed-Book-Cover.jpg|right|190px|thumb|Novel coauthored with [[Mabel Collins]]]] | ||

Despite her husband's death, Despard continued writing, although many of her works shifted from fiction and were centered on women’s rights and suffrage. Continuing with fiction, Despard co-authored, ''Outlawed. A Novel On The Woman Suffrage Question'' (1908) with fellow Theosophist, [[Mabel Collins]] (1851–1927). | Despite her husband's death, Despard continued writing, although many of her works shifted from fiction and were centered on women’s rights and suffrage. Continuing with fiction, Despard co-authored, ''Outlawed. A Novel On The Woman Suffrage Question'' (1908) with fellow Theosophist, [[Mabel Collins]] (1851–1927). | ||

| Line 35: | Line 48: | ||

=== Nonfiction === | === Nonfiction === | ||

* '''''The Christ That Is | * '''''[http://resources.theosophical.org/pdf/Authors/Despard/Despard_The_Christ_That_Is_To_Be.pdf The Christ That Is To Be]'''''. Glasgow: Star Publishing Trust, 1920s. 8 pages. First published in The Herald of the Star 6, no. 5 (May 1917): 253–56. | ||

* '''''The Needs of Little Children. Report of a conference on the care of babies and young children. Papers by Miss Margaret McMillan, Mrs. Pember Reeves, Dr. Ethel Bentham, Mrs. Despard'''''. 1912. | * '''''The Needs of Little Children. Report of a conference on the care of babies and young children. Papers by Miss Margaret McMillan, Mrs. Pember Reeves, Dr. Ethel Bentham, Mrs. Despard'''''. 1912. | ||

* '''''[Pamphlet issued by Home Rule for India League]'''''. [London] : Pelican Press, 1910s. Written with George Lansbury. 2 pages. Home Rule for India League. | * '''''[Pamphlet issued by Home Rule for India League]'''''. [London] : Pelican Press, 1910s. Written with George Lansbury. 2 pages. Home Rule for India League. | ||

* '''''Theosophy and the Woman's Movement'''''. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1913. Riddle of Life series; no. 4 | * '''''[https://archive.org/details/DespardTheosophyAndTheWomansMovement Theosophy and the Woman's Movement]'''''. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1913. Riddle of Life series; no. 4. | ||

* '''''A Voice from the Dim Millions; being the true history of a working woman'''''. London, 1891. At least 5 editions. | * '''''A Voice from the Dim Millions; being the true history of a working woman'''''. London, 1891. At least 5 editions. | ||

* '''''Was it Wise to Change?''''' London: Cassell, 1894. Reprinted from Cassell's Magazine. | * '''''Was it Wise to Change?''''' London: Cassell, 1894. Reprinted from Cassell's Magazine. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 57: | ||

* '''''Woman's Franchise and Industry'''''. Women's Freedom League, 1910s. | * '''''Woman's Franchise and Industry'''''. Women's Freedom League, 1910s. | ||

* '''''Woman in the New Era'''''. [London:] Suffrage Shop, 1910. "With an appreciation by Christopher Marie St. John." | * '''''Woman in the New Era'''''. [London:] Suffrage Shop, 1910. "With an appreciation by Christopher Marie St. John." | ||

[[File:Charlotte Despard portrait.jpg|left|180px|thumb|Portrait of Mrs. Despard]] | |||

== Additional resources == | == Additional resources == | ||

| Line 51: | Line 65: | ||

* Mulvihill, Margaret. '''''Charlotte Despard: a Biography'''''. London; Boston: Pandora, 1989. 211 pages. "Valiant Women" series. | * Mulvihill, Margaret. '''''Charlotte Despard: a Biography'''''. London; Boston: Pandora, 1989. 211 pages. "Valiant Women" series. | ||

* Roberts, Marie.; Mizuta, Tamae. '''''The Rebels: Irish Feminists'''''. London: Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1995. | * Roberts, Marie.; Mizuta, Tamae. '''''The Rebels: Irish Feminists'''''. London: Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1995. | ||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 80: | ||

[[Category:Imprisoned|Despard, Charlotte]] | [[Category:Imprisoned|Despard, Charlotte]] | ||

[[Category:Anti-vivisectionists|Despard, Charlotte]] | [[Category:Anti-vivisectionists|Despard, Charlotte]] | ||

[[Category:People|Despard, Charlotte]] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:49, 4 September 2024

Charlotte Despard was an Anglo-Irish writer and social activist.

Personal life

Born Charlotte French, 15 June 1844, third daughter of five and one son of Captain John Tracey William French (d. 1854) and Margaret (d. c.1865). Charlotte grew up lacking a formal education as was common for girls in Victorian England, a cultural habit she lamented. At approximately 19 she attended a finishing school in London. By this point her father had passed and her mother suffered a mental breakdown requiring institutionalization.

Charlotte married on 20 December 1870. Her husband, Maximilian Carden Despard (1839–1890), was a wealthy Anglo-Irish businessman and social radical who encouraged Charlotte to write. She wrote ten novels, seven of which were published. One of the earliest was Chaste as Ice, Pure as Snow (1874). One of the most famous was The Rajah's Heir, a novel (1890). Charlotte and her husband traveled Europe and India extensively. Yet, they never had children. She became a widow in 1890 when her husband was lost at sea. Losing her husband seems to have opened up possibilities for Despard for just after mourning for a few months she relocated to London slums and began working earnestly to bring relief and education to the poor.

Political and social activism

Despard’s earliest effort at social reform was establishing one of the first child welfare centers on 2 Currie St., Nine Elms, London, a location she maintained for almost two decades, a working men’s club, became a Poor Law Guardian in Lambeth, London, in 1894, and joined the Labour Party. She was known to wear simple black clothing and sandals. During this time she also became a suffragette joining the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). She and other members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) founded the Women's Freedom League:

it went on to become one of the largest British suffragette organizations gaining a membership of 4,000 soon after its founding in 1907. While the WFL wasn’t violent, it was militant: Led by vegetarian Charlotte Despard, members refused to pay taxes, citing lack of representation.[1]

By 1916, the Women's Freedom League had established the vegetarian Minerva Café, "which was part of a larger facility of meeting rooms and lodging. A surprising number of British suffragettes were vegetarians, and had been even before campaigning for the vote... While fighting for the right to vote, many passionately argued against vivisection, wearing fur coats and stuffed-bird hats, and eating meat."[2] The café was home to several feminist groups, as well as anti-war activists, anarchists, socialists, and naturists.[3]

Theosophical Society and other occult organizational connections

Despard, embracing her Irish heritage, converted to Roman Catholicism at the end of the 1890s and also joined the Theosophical Society on April 4, 1899.[4]. In the February 1917 issue of The Herald of the Star, Theosophist John Scurr calls Despard the “Beneficent Fairy of Nine Elms,” describing how she helped women save money, facilitated by the Married Women's Property Act of 1882. Prior to the act, the husbands owned the earnings of their wives and often took it for alcohol and other selfish desires. The act let wives designate Despard as the trustee of the funds, protecting their earnings from their husbands. Similarly, Scurr discusses how Despard cared for children injured through labor or play. “It was a lesson to anyone who is leading a soft, comfortable existence to see how children of seven or eight bore unflinchingly and with a brave face the smarting pain when ointments and lotions were applied.” He also describes her suffrage efforts and other work for the rights of women and the working poor. Seeming to fully embody Theosophy’s core principle of selflessness, Scurr ends writing of Despard, “Love and service are the dominant passions of her life. When the history of this time is written no one will occupy a higher place than the beneficent fairy of Nine Elms— Charlotte Despard.”[5]

Other sources mention Despard's work under Miss Eglantyne Jebb, who founded Save the Children Fund in 1919.[6][7]

Despard also maintained an interest in other esoteric and occult organizations in addition to the Theosophical Society. Light, A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research, notes that Despard gave a speech about “The New Womanhood” to The London Spiritualist Alliance, and organization which other theosophists participate, including A.P. Sinnett. Similarly, she gave the lecture, “The Spiritual Ideal of Womanhood” at the Ninth National Conference of Spiritualists, 2 July, 1911. And the June 1905 issue of the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research lists Despard as a new member.

Her most well-known Theosophical publication is her Theosophy and the Woman's Movement (1913).

Writings

Despite her husband's death, Despard continued writing, although many of her works shifted from fiction and were centered on women’s rights and suffrage. Continuing with fiction, Despard co-authored, Outlawed. A Novel On The Woman Suffrage Question (1908) with fellow Theosophist, Mabel Collins (1851–1927).

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 4 articles by or about Charlotte Despard.

Fiction

- Chaste as Ice, Pure as Snow. 1874.

- Jonas Sylvester. London, 1886.

- A Modern Iago: a Novel. London: Remington and Co., 1879. Two volumes.

- Outlawed. Subtitle: "A Novel on the Woman Suffrage Question." London: Henry J. Drane, 1908. Coauthored with Mabel Collins.

- The Rajah's Heir. A Novel. 1890.

- Songs of the Red Dawn. Dublin: Odhla Printing, 1932. Poetry. 16 pages.

- What the Shepherd Saw: a Tale of Four Moonlight Nights. New York: George Munro, 1881. A collection of very short Christmas stories by Thomas Hardy, Charlotte Despard, and others. Despard wrote The White Lady of Hillbury.

Nonfiction

- The Christ That Is To Be. Glasgow: Star Publishing Trust, 1920s. 8 pages. First published in The Herald of the Star 6, no. 5 (May 1917): 253–56.

- The Needs of Little Children. Report of a conference on the care of babies and young children. Papers by Miss Margaret McMillan, Mrs. Pember Reeves, Dr. Ethel Bentham, Mrs. Despard. 1912.

- [Pamphlet issued by Home Rule for India League]. [London] : Pelican Press, 1910s. Written with George Lansbury. 2 pages. Home Rule for India League.

- Theosophy and the Woman's Movement. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1913. Riddle of Life series; no. 4.

- A Voice from the Dim Millions; being the true history of a working woman. London, 1891. At least 5 editions.

- Was it Wise to Change? London: Cassell, 1894. Reprinted from Cassell's Magazine.

- Woman in the Nation. [London:] Women's Freedom League, 1910s.

- Woman's Franchise and Industry. Women's Freedom League, 1910s.

- Woman in the New Era. [London:] Suffrage Shop, 1910. "With an appreciation by Christopher Marie St. John."

Additional resources

- The Charlotte Despard Blogspot.

- Broderick, Marian. Wild Irish Women: Extraordinary Lives from History. Dublin: O'Brien, 2001.

- Linklater, Andro. An Unhusbanded Life: Charlotte Despard: Suffragette, Socialist, and Sinn Feiner. London: Hutchinson, 1980.

- Mulvihill, Margaret. Charlotte Despard: a Biography. London; Boston: Pandora, 1989. 211 pages. "Valiant Women" series.

- Roberts, Marie.; Mizuta, Tamae. The Rebels: Irish Feminists. London: Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1995.

Notes

- ↑ Ann Ewbank, "How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement" at Atlas Obcura July 03, 2018.

- ↑ Ann Ewbank, "How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement" at Atlas Obcura July 03, 2018.

- ↑ Nick Heath, The Minerva Café" at Libcom.org. Jan 1 2017.

- ↑ Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 2, entry 16690 (website file: 2A/18).

- ↑ Scurr, John. “The Beneficent Fairy of Nine Elms.” The Herald of the Star 6, no. 2 (February 1917): 107–9.

- ↑ L. Haden Guest letter to George Arundale, "On the Watch-Tower" The Theosophist 41 no.8 (May, 1920): 107.

- ↑ Our Founder, Eglantyne Jebb at Save the Children website.]