Neoplatonism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude. It is a kind of "technique of passivity," whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. <ref>Aubry, Gwenaelle. <i>Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism.</i> In: <i>The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism.</i> Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48</ref> | Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude. It is a kind of "technique of passivity," whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. <ref>Aubry, Gwenaelle. <i>Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism.</i> In: <i>The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism.</i> Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48</ref> | ||

Iamblichus focused more closely than Plotinus on the soul’s indwelling within the body and on the actions it performs alongside it. In what remains of his treatise <i>On the Soul</i>, he reviews all sorts of historical theses about the composition, powers and activities of the soul, and does not hesitate to engage his Neoplatonic predecessors. <ref>Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25</ref> | Iamblichus focused more closely than Plotinus on the soul’s indwelling within the body and on the actions it performs alongside it. In what remains of his treatise <i>On the Soul</i>, he reviews all sorts of historical theses about the composition, powers and activities of the soul, and does not hesitate to engage his Neoplatonic predecessors. | ||

He also wrote a whole treatise <i>On virtues</i>, which is lost but whose content can be inferred from later sources. In addition to this, references to ethics and politics can be gathered from his extant works. <ref>Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25</ref> | |||

Revision as of 15:05, 6 May 2025

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Neoplatonism is a philosophical school that reinterpreted and expanded upon the ideas of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, particularly focusing on the concept of a single, supreme source of being, goodness, and reality. It argued that the world which we experience is only a copy of an ideal reality which lies beyond the material world. This ideal reality is comprised of three levels and the final level cannot be grasped by philosophy but can only be reached through mystical experience. [1] They called the single source of being the "One", who they saw as the source of all other beings and things, which emanate from it in a hierarchy.

Neoplatonism and Theosophy are united by a shared foundation in mystical and philosophical thought. Both explore central themes such as the One, the emanation of the cosmos from a divine source, absolute consciousness, the cyclical nature of existence, the hierarchy of divine beings, and the soul.

History of Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism arose in the 3rd century AD as a profound evolution of Platonic philosophy, shaped by the rich and diverse intellectual currents of late Hellenistic thought and religious traditions. Rather than representing a rigid system of doctrines, Neoplatonism is best understood as a dynamic lineage of thinkers united by a shared philosophical vision. Central to this vision is the concept of monism—the belief that all of existence ultimately emanates from a single, ineffable source known as the One.[2]

Ammonius Saccas

The first authentic Neoplatonist was probably Ammonius Saccas (175-250 A.D.), who taught in Alexandria during the last part of the first quarter of the third century. Since he left no writings, his claim to fame rests upon the success of his famous pupils: Plotinus, the two Origens, the philologist Longinus, and Herennius. Although some of them refer to his thought occasionally, it is impossible to determine which of their views were inspired by him. [3]

Ammonius was born to devout Christian parents and sent to a Christian school, where he learned about the life of Christ. But he soon noticed striking similarities between the story of Christ and that of Krishna—both born of a virgin, both persecuted by tyrants, both said to have died on a cross. Could these be legends? Were there others like them in different cultures? When he questioned this, the priest insisted there was only one true Christ—all others were false. He was told to believe, but he longed to understand. So Ammonius left the school and set out on a path of sincere inquiry.[4]

When Ammonius Saccas laid the foundations for that which is called “Neoplatonism”, the philosophical system underwent some changes. He maintained that the great principles of all philosophical and religious truth were to be found equally in all sects; that they differed from each other only in their method of expressing them, and in some opinions of little importance. [5]

Plotinus

Plotinus (203/204 or 205-270 A.D.) was the first notable Neoplatonist. His birthplace is uncertain, since it is given as Lycon by Eunapius and as Lycopolis by Suidas. Plotinus, according to Porphyry, attended the lectures of various professors at Alexandria but was not satisfied until he came upon Ammonius Saccas at the age of 28. [6]He remained with him for 11 years. At the end of that time Plotinus determined to visit Persia and India so that he could study the Eastern philosophies at first hand. At the age of thirty-nine he joined the army of the Emperor Gordian and went with him to the Far East. After the destruction of Gordian's army Plotinus returned to Antioch and finally went to Rome during the reign of the Emperor Philip. [7]

He ended up in Rome around 240 A.D. and obtained great renown and was respected by all. It is said that during the 26 years he lived in Rome he did not have a single enemy. He was often approached for help and advice, took in orphaned children acting as their guardian, and led a deeply spiritual life. Even the Emperor Gallienus, one of the greatest villains respected and honored him. [8] [9]

In Rome he founded a school of philosophy. At first, his instruction was entirely oral, until his most talented pupil, Porphyry, persuaded him to commit his seminars to the page. [10] Thus, he began to write when he was fifty years old and during the following ten years wrote twenty-one books which were circulated among his friends and pupils. Before his death, Plotinus had written fifty-four books dealing with physics, ethics, psychology and philosophy. Plotinus was thoroughly conversant with the doctrines of the Stoics and Peripatetics and found it useful to employ these familiar ideas in his writings. There was no geometrical, arithmetical, mechanical, optical or musical theorem with which he was not acquainted, although he does not seem to have applied these sciences to "practical" purposes. [11] Plotinus died at the age of sixty-six. It is said, that at the moment of his death a Dragon, or Serpent, glided through a hole in the wall and disappeared -- a fact highly suggestive to the student of symbolism. In later years Porphyry, his devoted pupil, summed up Plotinus' life in these words:

”He left the orb of light solely for the benefit of mankind. He came as a guide to the few who are born with a divine destiny and are struggling to gain the lost region of light, but know not how to break the fetters by which they are detained; who are impatient to leave the obscure cavern of sense, where all is delusion and shadow, and to ascend to the realms of intellect, where all is substance and reality. [12]

After Plotinus’ death, Porphyry edited and published his writings, arranging them in a collection of six books consisting of nine essays each (the so-called “Enneads” or “nines”). [13]

Malchus Porphyry

The real name of Porphyry (232-c.304 A.D.), a native of Tyre, was Melek (a king). This name was rendered by Longinus into Porphyrius (the royal purple), as its proper equivalent, and so he has come down through history under the name of Porphyry. While there is no doubt that Porphyry had Jewish blood in his veins, it is apparent that he never followed the Hebrew doctrines but was thoroughly Hellenized and a true "pagan." [14] Porphyry, the editor of Plotinus's Enneads, stands at the origin of a new evolution of Neoplatonism: the infusion into it of the Chaldean Oracles. This is a collection of texts from the second to third centuries CE, whose redaction has been attributed (uncertainly) to Julian the Theurgist. One finds in them, in an oracular form, a theoretical content very much influenced by Middle Platonism and Neoplatonism. But this metaphysical content mingles with ritual and liturgical prescriptions, presented as so many ways to reach the divine.

The Chaldean Oracles thus precipitate both a theological and a theurgical turn in Neoplatonism. The Oracles play the role of a revealed text, so much so that one may see in them the "Bible" of post-Plotinian Neoplatonists.

Thus, like Plato, Plotinus also suffered the fate of having his philosophy altered by his disciples.

Porphyry and others tried to conciliate the content of the Oracles with the doctrines of Plato and Plotinus. This theological turn is also a theurgical one, for now rituals aiming at union with the divine come to the fore. In short, a new path to the mystical experience is introduced, distinct from the inner conversion prescribed by Plotinus. Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude; rather, it is a kind of “technique of passivity,” whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. [15]

Amelius Gentilianus

Amelius Gentilianus was a Neoplatonist philosopher and writer of the second half of the 3rd century. He began attending the lectures of Plotinus in the third year after Plotinus came to Rome >[16] and stayed with him for more than twenty years, until 269, when he retired to Apamea in Syrica, the native place of Numenius, a Greek philosopher. He was responsible for the conversion of Porphyry to Neoplatonism. His principle literary work was a treatise in forty books, arguing against the claim that Numenius should be considered the original author of the doctrines of Plotinus. [17][18]

Iamblichus

Iamblichus (ca. 242–ca. 325 A.D.) was born in Chalsis, in Coele-Syria, at about the middle of the third century. Based on fragments of his life which have been collected by impartial historians, he was a man of great culture and learning, and renowned for his charity and self-denial. His mind was deeply impregnated with Pythagorean doctrines, and in his famous biography of Pythagoras he has set forth the philosophical, ethical and scientific teachings of the Sage of Samos in full detail. He was also a profound student of the Egyptian Mysteries and expressed his determination to make public what hitherto had been taught only in the Mystery Schools under the greatest secrecy. [19]

He exerted considerable influence among later philosophers belonging to the same tradition, such as Proclus, Damascius, and Simplicius. His work as a Pagan theologian and exegete earned him high praise and made a decisive contribution to the transformation of Plotinian metaphysics into the full-fledged system of the fifth-century school of Athens, at that time the major school of philosophy, along with the one in Alexandria. His harsh critique of Plotinus’ philosophical tenets is linked to his pessimistic outlook on the condition of the human soul, as well as to his advocacy of salvation by ritual means, known as “theurgy”. [20]

In fact, he advocated theurgy as the exclusive path to salvation. This internal scission of Neoplatonism partly rests on a disagreement as to the nature of the soul. Iamblichus believed, as did Aristotle, that the soul is nothing else than the life of the body. He refused to accept the idea of a separate soul whose power one would have to activate in oneself.

Theurgy does not require any sort of human aptitude. It is a kind of "technique of passivity," whose aim is to make oneself totally receptive to divine power. The theurgical turn of Neoplatonism, therefore, goes together with the dislocation of the peculiar conjunction between rationalism and mysticism, which appeared in the philosophies of both Plato and Plotinus. [21]

Iamblichus focused more closely than Plotinus on the soul’s indwelling within the body and on the actions it performs alongside it. In what remains of his treatise On the Soul, he reviews all sorts of historical theses about the composition, powers and activities of the soul, and does not hesitate to engage his Neoplatonic predecessors.

He also wrote a whole treatise On virtues, which is lost but whose content can be inferred from later sources. In addition to this, references to ethics and politics can be gathered from his extant works. [22]

Proclus

Proclus of Athens (412–485 C.E.) was the most authoritative philosopher of late antiquity and played a crucial role in the transmission of Platonic philosophy from antiquity to the Middle Ages. For almost fifty years, he was head of the Platonic ‘Academy’ in Athens. He was an exceptionally productive writer and composed commentaries on Aristotle, Euclid and Plato, and systematic treatises in all disciplines of philosophy. Proclus had a lasting influence on the development of the late Neoplatonic schools not only in Athens, but also in Alexandria, where his student Ammonius became the head of the school. [23]

Like Plotinus, he taught that man's ultimate goal is union with the Ultimate but added that theurgy can be an aid higher than the practice of dialectics. He was highly influenced by Plato's Timaeus and once stated that if it were in his power to do so he would withdraw all books from human knowledge except the Timaeus and the Chaldean Oracles.

In two of his works, Elements of Theology and Plato's Theology, he provided elaborate explanations of Neoplatonism. Both were fairly well circulated and had no small influence upon Byzantine, Arabic, and early medieval Latin Christian thought. [24]

The School

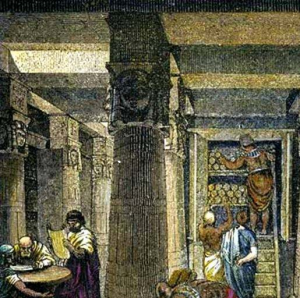

Saccas founded his school in 194 AD in Alexandria, which was at the time the place for intellectual endeavor attracting scholars from all over the world. They came not only to the great library but also because there was a great enthusiasm for ancient Greek wisdom, and the teachings of Pythagoras and Plato, in particular. In fact, with this emphasis on Platonic study in Alexandria at the time, some present philosophers are finding indications in the old literature of an "unwritten philosophy" that Plato shared with a few select students and a recognition of the role played by the Mystery Schools in the past eras of Grecian culture.

The existence of an inner and outer circle of students seems to be the norm in the Mystery Schools. Saccas’ school also had a division; there was the exoteric and esoteric. Students were further divided into classes - the neophytes, initiates and masters. The rules of the school were copied from those used in the Mysteries of Orpheus. "What Orpheus delivered in hidden allegories, Pythagoras learned when he was initiated into the Orphic Mysteries, and Plato next received a perfect knowledge of them from Orphic and Pythagorean writings."[25]

In the Orpheus tradition the manifested world is inseparable from divine essence, having emanated from it and will eventually return to that divine essence. Of course, many reincarnations and transmigrations are necessary for purification before this return can happen. There are three distinct characteristics of the Orpheus system. First is the idea of a supreme essence. Second is the idea of a human soul which was emanated from that divine essence. Third is the practice of Theurgy, the art of using the divine powers of man to direct the forces of nature.

One of the primary goals of Ammonius Saccas and his school was unity. He wanted to reconcile all religious sects, all peoples and all nations under one common faith, to form a Universal Brotherhood in the hopes of ending violence by uniting all with a common theology. To do this he needed to show that there was one source from which all religions came. With his students he explored the School the Vedantic thought, Zoroastrianism, the Jewish Kabala, Buddhism, ancient Egypt and compared them with the philosophies of Plato and Pythagoras. He wanted to show that there was a prisca theologia and all the various differences were simply variations on the same theme.

Beliefs

Unity. All faiths have a common binding origin. Neoplatonism calls for recognition of that basis and an understanding of our brotherhood with all mankind.

In a quote by Madame Blavatsky from The Keys to Theosophy she states that Ammonius Saccas had asserted that the ideas from his Eclectic Theosophical System “dated from the days of Hermes.” If we follow these teachings back to Hermeticism, Saccas studied Plato, Plato studied Pythagoras, Pythagoras studied in Egypt, Egypt was settled by the survivors of Atlantis, and Atlantis was settled by the survivors of Lemuria where Hermes was known to be a King-Instructors. See Hermeticism.

In Hermeticism Nous is the name of the One, the Source. In Hermeticism Source created Nous II who created the earth. This first emanation, Nous II, or intellect, relates to the Forms in Plato's philosophy.

Neoplatonists believed in one Supreme Eternal Unknown and Unnamed Power which governs the universe by immutable and eternal laws. They also believed in a hierarchy of mortal and immortal beings, emanations from the One, both physical and non-physical associated with earth and its development. Sometimes called intermediate gods, angels, devas or demons, Iamblichus is noted for adding hundreds to the list. An interesting note here about Iamblichus, according to H. P. Blavatsky he believed in and practiced “ceremonial magic and practical theurgy” which the other neo-Platonists felt was “dangerous.” Hypatia of Alexandria, whom we will discuss later, was also noted for her skill at theurgy.

Metempsychosis or reincarnation is believed to have first appeared in the Orphic Religion in Thrace some time before the fifth century BC. Orpheus, the founder, was believed to be a poet. His philosophy taught that the body and soul are united in a sort of contract. The immortal soul longs for freedom while the body holds it as a sort of prisoner. Upon death the contract is temporarily void. The soul is free for a while until the next round of incarnation. The round of freedom and incarnation is inexorable without the grace of redeeming gods. The gods calls them to turn to God by ascetic piety of life and self-purification: the purer their lives the higher their next incarnation will be, until the soul has completed the spiral ascent of destiny to live forever as God from whom it came to begin with. Dionysus, in particular, is to be sought in this intervention of reincarnation.

Why Dionysus? In mythology, Dionysus, aka, Bacchus, is the son of Zeus in one of his incarnations. (Interesting that gods reincarnate too.) He is killed by the Titans and eaten by them, all but his heart which Athena manages to save. Athena tells Zeus of the crime by the Titans. Zeus hurls a thunderbolt at the Titans and from the resulting soot, sinful man (represented by the Titans) and divine soul (represented by Dionysus) are born. So sinful body will return time and time again with divine soul in bondage. Such are the teaching of Orpheus which found their way into Neoplatonism.

We learned that reincarnation was necessary for the soul to purify itself in order to reunite with the One. What made the soul impure to begin with unless simply the descent into matter caused this? In Hermeticism matter, or Nature, is not impure but a beautiful environment to be enjoyed and appreciated. According to Plotinus, matter is to be identified with evil. “Matter is what accounts for the diminished reality of the sensible world, for all natural things are composed of forms in matter. The fact that matter is in principle deprived of all intelligibility and is still ultimately dependent on the One is an important clue as to how the causality of the latter operates. If matter or evil is ultimately caused by the One, then is not the One, as the Good, the cause of evil? In one sense, the answer is definitely yes. As Plotinus reasons, if anything besides the One is going to exist, then there must be a conclusion of the process of production from the One. The beginning of evil is the act of separation from the One by Intellect, an act which the One itself ultimately causes. The end of the process of production from the One defines a limit, like the end of a river going out from its sources. Beyond the limit is matter or evil.”[26]

If we can replace “intelligibility” with “consciousness” modern scientists, as well as, Rudolf Steiner would take exception to the statement “matter is in principle deprived of all intelligibility.” Matter, all matter, has some form of consciousness. A modern physicist would propose that any object is held together by a sort of consciousness, an intelligence of the very subatomic particles that “chose” to remain in an organized form to make a solid object. Spinning protons and neutrons somehow remain in place instead of spinning off into the cosmos. Steiner says that rocks, plants, animals, all have a form of consciousness. We may not be familiar with its form of consciousness but at one point in our development as a species we did experience these lower forms of consciousness which with sensitivity can be communicated with and understood.

The Neoplatonists seem to be saying that matter is evil because it gets in the way of the human being making their return to the One. This is simply a matter of choice. It does not have to be an impediment to progress. On the subject of evil we end with the Neoplatonic view that evil is the absence of light, or intelligence but not an entity unto itself. There is no personification of evil in a Satan, Lucifer, the Devil, Beelzebub or Prince of Darkness causing havoc with innocent souls, instead, the innocent souls lack the light of intelligence to prioritize the goal of purification and return to One.

Plotinus and Origen believed the descent of the soul into the material was a necessary event to unfold the divine Intellect, or God. The descent itself is not an evil, for it is a reflection of God's essence but both Origen and Plotinus place the blame for experiencing this descent as an evil squarely upon the individual soul. They believed a rational soul will naturally choose the Good, the God, the One, and that any failure to do so is the result of forgetfulness or ignorance. So we have free will to choose the One or be caught up in the material world. Evil is thus the absence of light or knowledge.

Reincarnation is necessitated by karma. What you sow you shall reap in one life or the next. There is a curious balance of energy that seems to be required before one can be purified and move on.

Theurgy, the art of using the divine powers of man to rule the blind forces of nature was an accepted belief of Neoplatonists. As mentioned earlier Iamblichus was a famous practitioner of Theurgy. He believed that the soul, once descended into Nature, was so enamored by it that it became blind to the higher aspects of spiritual life. He thought the spell of matter needed to be broken by physical ritual which involved some carefully chosen items called sunthemata, “items that had the property of revealing and communicating some aspect of the divine, and could be physical objects (stones, plants, animals), perfumes, music, actions, songs or poetry. A ritual immersion in sunthemata had the effect, like a magnifying glass, of concentrating a divine aspect on the soul and awakening the corresponding aspect in the soul. Ritual was a natural adjunct to the worldview of Iamblichus: philosophy prepared the mind, and ritual awakened the interior eye of the soul to the natural orders of the Kosmos. In time the soul itself became sunthemata, a conscious channel for the divine influx capable of demiurgic action and co-creation.”[27]

There were many diverse schools of thought at this time but because of opposition from the burgeoning numbers of Christians in particular, Neoplatonists decided to move their school to Athens.

The Rise of Catholicism

Plato was born four hundred years before Jesus so Christianity was not a subject he addressed yet for the Neoplatonists in the third and fourth centuries it was a major issue of the day. The thinkers and philosophers and religionists from traditions, like Gnosticism and Hermeticism, were also part of the mix in the maelstrom that was the formation of the Catholic Church.

Christianity took various forms in the three centuries after the death of Jesus but the rise of Catholocism was the work of the Roman Emperor Constantine. The word “catholic” is derived from the “Greek adjective καθολικός (katholikos), meaning "universal") which comes from the Greek phrase καθόλου (katholou), meaning "on the whole", "according to the whole" or "in general."[28] It was a political system designed to control the masses, the general population.

The supposed conversion of Constantine to Christianity took place after an alleged psychic vision. Christ himself supposedly appeared and spoke to Constantine, telling him to place the Christian cross on his battle flag and he would defeat his enemy Maxentius. Constantine did as he was told in the vision. He knew that many of his soldiers were followers of a new religious sect called Christianity so carrying a flag with the symbol of their savior was inspiring to his men. He marched into battle and defeated Maxentius.

Constantine was a pagan, a worshipper of the sun god and he remained so until his death but Christianity had a lot to offer a murderer like Constantine. After his defeat of Maxentius, Constantine murdered five members of his own household and later he killed his own wife and son. Eventually all of these murders began to weigh upon his conscience. He had been fighting under the banner of Christ for twenty years but he turned to the pagan religions for absolution. “He was told that no pagan religion offered absolution for such crimes as his. He then turned to the Christian Church, and was informed that Christian baptism would expiate any crime, irrespective of its magnitude. At the same time he was advised that baptism might he deferred to the day of his death without losing any of its efficacy.”[29]

What a deal! Murder anyone you like, be baptized at your death and go to heaven. How could a tyrant like Constantine even consider not encouraging such a convenient religion? So encourage it he did. Rome became Catholic, after some flushing out of the details into an official creed. This was neatly accomplished at the Council of Nicea in 325.

So in the midst of Constantine and the Roman Emperors who followed him sponsoring their new religion Catholicism many pagan schools, like Neoplatonists continued. “Christians claimed that Jesus was a unique character, while the entire pagan world knew that the legends surrounding Jesus' life were identical with those of the pagan gods.”[30] They knew Catholics were inventing a story about Jesus using pagan symbols, pagan holidays, pagan beliefs and half-truths from the life of Jesus. Yet the Catholic Church was solidifying into a political powerhouse to crush any opposition.

Hypatia

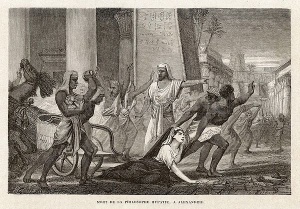

There were many famous Neoplatonists - Plotinus, Porphyry and Iamblicus – but perhaps the greatest and certainly the most tragic was Hypatia. Hypatia was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher. She was living in Athens when she first became acquainted with the Neoplatonic school. Later she moved to Alexandria where she became the head of the Neoplatonic school and also taught philosophy and astronomy.

“Hypatia brought Egypt nearer to an understanding of its ancient Mysteries than it had been for thousands of years. Her knowledge of Theurgy restored the practical value of the Mysteries and completed the work commenced by Iamblichus over a hundred years before. Continuing the work of Ammonius Saccas, she showed the similarity between all religions and the identity of their source.[31]

Under the leadership of this astonishing woman Neoplatonism thrived. She publically debated and analyzed the metaphysical allegories from which Christianity had pirated its dogmas and repeatedly and publically embarrassed the new church. It has been suggested that if the Neoplatonic school had continued under Hypatia’s leadership that entire fraud of the Catholic Church would have been exposed. But the Catholic Church had ways of dealing with opposition, especially from upstart women who obviously had not learned the rightful place of women according to the Catholic Church.

One afternoon in 414 a group of Cyril’s monks, led by Peter the Reader, descended on Hypatia as she left the Museum where she had just finished teaching a class. They stripped her naked and dragged her to a nearby church where at the altar of the church Peter the Reader struck her dead. The crowd then dragged her dead body into the street where they scraped the flesh from her bones with oyster shells and burned what remained in a bonfire.

The Legacy

With Hypatia’s death the School Neoplatonism came to an end, being officially closed by Justinian in 527. Many Neoplatonists fled to Athens and some escaped to the Far East to avoid the persecution of Justinian and the Dark Ages began with the Catholic Church in the lead. And the Catholic Church like radical Islamism today tolerated no one who did not adhere strictly to their system. Paganism, which was anything that was not Catholicism, was made illegal by an edict of the Emperor Theodosius I in 391. Eventually, the Inquisition was instituted to destroy any deviance from Catholic doctrine. Neoplatonism, along with many other schools of thought, like Hermeticism and Gnosticism went underground.

But in 1438 the underground thoughts swelled to the surface. Cosmo de Medici met, Gemisthus Pletho, a passionate Platonist, who inspired him to found a Platonic Academy in Florence. Cosmo selected Marsilio Ficino, the son of his chief physician, to translate the great works of Greek and Eastern philosophy that had been forbidden by the Catholic Church. Eventually he translated Plato, Hesiod, Proclus, Orpheus, Homer, Hermes Trismegistus, Plotinus, Iamblichus, Proclus and Synesius. Ficino could not help but be profoundly influenced by these profound thinkers. He became a major proponent of Neoplatonic and Hermetic thought and that opinion was carried on by others, many of whom lost their lives in the Holy Inquisition for having an allegiance to anything other than the Catholic Church.

Despite its pagan origins, Neoplatonism has had a major influence on later unorthodox Christian, Jewish and Islamic thought. Today and in recent history those who could be considered Neoplatonists include Goethe, Schiller, Schelling, Hegel, Coleridge, Emerson, Rudolf Steiner, Carl Jung, Jean Gebser and any Theosophist.

Neoplatonism and Theosophy

THIS SECTION IS UNDER CONSTRUCTION

THIS SECTION IS UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Books

Mills, Joy. The Keys to Theosophy: H. P. Blavatsky : an Abridgement. , 2013. Internet resource. P. 1.

Harris, R B. Neoplatonism and Contemporary Thought. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. Print.

Harris, R B. The Significance of Neoplatonism. Norfolk, Va: International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University, 1976. Print.

Online resources

Articles

- The Eclectic Philosophy by Alexander Wilder.

- Neoplatonism in Theosophy World.

- Plotinus in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Theurgy and Magic in Hermetic Kabbalah website.

- Hypatia of Alexandria (ca. 370-415 A.D.) in Tripod.com.

Audio

Video

- Turning-Points for the West: From Pythagoras and Plato through Gnosticism and Neoplatonism by Stephan Hoeller and Tony Lysy, presented on September 11, 2004 at the Theosophical Society in America.

- All About Platonism series by Mindy Mandell.

- Transformation. Added January 31, 2022. 28 minutes.

- Things in Themselves. Added December 6, 2021. 27 minutes.

- Dialectic. Added January 17, 2022. 17 minutes.

- Menexenus. Added April 12, 2021. 24 minutes.

- Purification. Added February 7, 2022. 29 minutes.

- Plotinus 1:6 Beauty. Added January 24, 2022. 27 minutes. Discusses Neoplatonism.

- 12 Gods of the Phaedrus. Added January 10, 2022. 13 minutes.

Notes

- ↑ National Gallery NG 200. Neoplatonism https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/glossary/neoplatonism. Accessed on 5/5/25

- ↑ World History Edu. What is Neoplatonism.1/31.25. https://worldhistoryedu.com/what-is-neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/25.25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS.Ammonius SaccasTHEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 2, December, 1936, pages 53-59; number 9 of a 29-part series

- ↑ Dr. Siemons, Jean-Louis. Theosophical History, Occasional Papers, Vol. III. Ammonius Saccas and his “Eclectic Philosophy” as presented by Alexander Wilder.Theosophical History; Fullerton, Ca. 1994, p. 9

- ↑ Copleston, S.J. A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 463 https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ Dr. Hartmann, Franz. In the Pronaos of the Temple of Wisdom. Chapter 2. 1890. https://sacred-texts.com/sro/ptw/ptw04.htm Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ Copleston, S.J. A History of Philosophy. Volume I. Greece and Rome. Page 464 https://archive.org/details/AHistoryOfPhilosophyV1FCoplestone/mode/2up?view=theater Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ From GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. Plotinus THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 3, January, 1937, Pages 101-110; (Number 10 of a 29-part series)

- ↑ Neoplatonism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neoplatonism/ Accessed on 4/22/25

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.

- ↑ Aubry, Gwenaelle. Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism. In: The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism. Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48

- ↑ Porphyry.Vita Plotini. p.3. Access through subscription.

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 8

- ↑ Porphyry.Vita Plotini. 16-18. Access through subscription.

- ↑ GREAT THEOSOPHISTS. IAMBLICHUS: THE EGYPTIAN MYSTERIES THEOSOPHY, Vol. 25, No. 5, Februar, 1937. Pages 149-57; Number 11 of a 29-part series.

- ↑ Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Aubry, Gwenaelle. Plato, Plotinus, and Neoplatonism. In: The Cabridge Handbook of Western Mysticism and Esotericism. Edited by Alexander Magee. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2016, pp. 38 - 48

- ↑ Iamblichus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/iamblichus/ Accessed on 4/29/25

- ↑ Proclus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/proclus/. Accessed on 4/30/25

- ↑ Harris, Baine. The Significance of Neoplatonism. International Society for Neoplatonic Studies, Old Dominion University. Norfolk, Va. 1976, p. 11

- ↑ http://www.wisdomworld.org/setting/saccas.html

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plotinus/

- ↑ http://www.digital-brilliance.com/themes/theurgy.php

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_term_%22Catholic%22

- ↑ http://www.wisdomworld.org/setting/hypatia.html

- ↑ http://www.wisdomworld.org/setting/saccas.html

- ↑ http://plato2051.tripod.com/hypatia_of_alexandria.htm