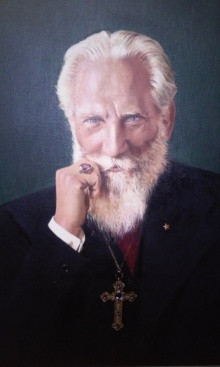

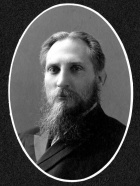

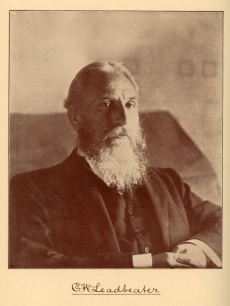

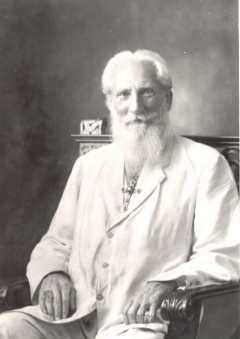

Charles Webster Leadbeater

ARTICLE UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Charles Webster Leadbeater was an English Theosophist associated with the Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Chennai, India. He was best known for his extensive writings, his clairvoyant observations, and his involvement in "discovering" and raising Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Early life

Charles Webster Leadbeater was born in Stockport, Cheshire, England to Charles Leadbeater, a railway contractor's clerk, and his wife Emma. The date of his birth was February 16, 1854, and his christening took place on March 19, 1854.[1] The England Censuses of 1861 and 1881 confirm that year. However, in the early 1880s, Leadbeater gave his birth date as February 17, 1847. That date appears in the 1891 census, in his passport, and is also reflected in passenger lists and other records. The earlier year, 1847, is the same year that Leadbeater's close associate Annie Besant was born.

According to C. Jinarajadasa, the Leadbeater family was Norman French in origin, with name Le Batre (the builder), later Englished to Leadbeater. One branch of the family followed "Prince Charlie" of the Stuart dynasty, and adopted the custom to christen the eldest son "Charles".[2]

In 1858 the family went to Brazil, and his father died a few years later, in 1862.

In December 21, 1879, following the footsteps of his uncle, Mr. Leadbeater was ordained a priest in the Church of England. He was assigned as "a curate in a parish in Hampshire called Bramshott, and lived with this mother at a cottage called 'Hartford'... The Rector of the parish was the Rev. W. W. Capes... his wife Mrs. Capes was C. W. L.'s aunt."[3]

Despite his connection to the Church of England, Mr. Leadbeater always kept an open mind for things that did not fall within orthodox Christianity, such as psychic and Spiritualistic phenomena. Whenever he heard of ghosts or haunted houses he conducted his own investigations. He also attended the lectures given by Annie Besant (then an atheist) at the Hall of Science.

Introduction to Theosophy, Blavatsky, and the Masters

In 1883, Mr Leadbeater read a copy of A. P. Sinnett’s book The Occult World and became very interested in Theosophy. He met the author, who was at the time receiving letters from two of the Masters of Wisdom, and joined the London Lodge of the Theosophical Society, in November 1883. He was immediately attracted to the ideal of the Masters and felt that each "should set before himself the definite intention of becoming a pupil of one of the great Adept Masters".

One day, while investigating Spiritualistic phenomena with renowned medium and Theosophist William Eglinton, one of the latter's Spirit-guides named "Ernest" assured he could transmit a letter from Mr. Leadbeater to the Masters. On March 3, 1884, he wrote a letter to Master K.H. offering himself as a chela so that he could "learn more of the truth". He sent the letter to Mr. Eglinton, who placed it in a box he had for Ernest's use, and from which it eventually disappeared. Several months passed and he did not receive any reply.

In the meantime, he met Mme Blavatsky, who arrived at London on April and unexpectedly attended a rather troubled meeting of the London Lodge where new officers were being elected. He described the "truly tremendous impression" that Mme. Blavatsky had on him. Her plan was to stay in Europe until November 1st of that year, when she was to sail for India. On October 30, two days before her departure, Mr. Leadbeater traveled to London to say good-bye to HPB. He stayed the night with the Sinnetts. That evening HPB informed him that "D.K." had said that the Master had sent a reply to his letter of March 3rd. On the next day, Mr. Leadbeater returned to his house and found the Master's letter, which opened as follows:

Last spring – March the 3rd – you wrote a letter to me and entrusted it to "Ernest". Tho' the paper itself never reached me – nor was it ever likely to, considering the nature of the messenger – its contents have.[4]

In the letter the Master said that a member should "force" the Master to accept him as a chela by doing good works for humanity, working on self-purification, and making sacrifices for the Theosophical cause. He also warned CWL that he would have to atone for the collective karma of the Christian clergy to which he belonged. Finally, the Master suggested that he could go to Adyar to work for a few months. The letter closes with the following words:

So now choose and grasp your own destiny, and may our Lord's the Tathagata's memory aid you to decide for the best. K. H.[5]

He decided to follow the Master's suggestion. However, he found out he could not take a leave of absence from his position in the local Church school, of which he was manager – he would have to resign to it. He decided to go back to London to talk to Mme. Blavatsky (who was leaving London the next morning) and, through her agency, ask the Master whether he wanted him to take this more drastic action. Late that night, in a gathering of some Theosophists that had come to say farewell to HPB, the answer was precipitated on her open hand, witnessed by several people. It said:

Since your intuition led you in the right direction and made you understand that it was my desire you should go to Adyar immediately – I may say more. The sooner you go the better. Do not lose one day more than you can help. Sail on the 5th if possible. Join Upasika at Alexandria. Let no one know you are going and may the blessing of our Lord, and my poor blessing shield you from every evil in your new life. Greeting to you my new chela. K.H. Show my notes to no one.[6]

Early Theosophical work

In 1886 Leadbeater was a member of the small headquarters staff at Adyar, along with President-Founder Colonel Olcott, A. J. Cooper-Oakley, and a few Indian workers. Very little money was coming into Adyar in those days apart from small incomes made selling books and coconuts. "When the [carriage] horses died one after another, for several months Mr. Leadbeater, as acting editor of The Theosophist had to walk the seven miles to Madras with proofs, etc."[7]

When Olcott founded Ananda College in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on November 1, 1886, he installed Leadbeater as the first principal. While in Ceylon, Leadbeater served as General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in that country from 1888-1889.[8]

Accusations, resignation and return to the Society

In early 1900, some adolescents were put under Leadbeater's education to be trained in occultism. Some of them, who felt the pressure of sexual thoughts, were advised to masturbate to ease the urge. This advise was highly controversial at a time when even doctors held the opinion that masturbation could lead to insanity. Leadbeater argued that this view was mistaken, and that the accepted alternative of having encounters with the prostitutes was degrading to the women, and created bad karmic and moral consequences for those involved in illegitimate sex.

He also maintained that, when masturbation was dealt with as a purely physiological act, it was less problematic from an occult point of view than indulging in sexual thoughts. This view finds precedent in the writings of H. P. Blavatsky. When asked about the "sexual force" she answered:

This force is vital, creative, and a sort of reservoir. It may be lost by mental action as well as by physical. In fact its finer part is dissipated by mental imaginings, while physical acts only draw off the gross part, that which is the (upadhi) for the finer.[9]

In 1906, when some of the parents learned about these practices, they became very upset. A commission of the American branch of the Society was appointed to investigate the facts causing great controversy. Leadbeater offered his resignation to "save society from shame," and Henry Steel Olcott accepted it. Later, in 1909, he was reinstated in the Theosophical Society, under the presidency of Annie Besant.

International lecture tours

Krishnamurti

In May, 1909, C. W. Leadbeater ran into 13-year old J. Krishnamurti who was playing in the beach, exhibiting "the most wonderful aura he has ever seen, without a particle of selfishness." Although Theosophist and scholar Ernest Wood, who had tried to help the boy with his homework, considered him to be dim-witted, Leadbeater predicted that Krishnamurti would become a spiritual teacher and a great orator "much greater" than even Annie Besant.[10]

CWL nourished, educated and trained young Krishnamurti and his brother Nityananda. Another controversy was raised by an Indian servant in 1913. The reason was that CWL taught the two boys to take showers naked, so that they could wash properly, which opposed the traditional Indian custom of keeping a piece of cloth around the waist. This was used by the father against him in a case in India in relation to the legal guardianship of the brothers. The judge regarded that these were "immoral ideas" and ruled against Besant and Leadbeater.[11][12] Annie Besant appealed to the court in London and won the case.

As Krishnamurti became a teenager, he gradually began to resent the discipline imposed on him. He left Adyar to live in Europe and Leadbeater moved to Australia. Krishnamurti grew rebellious about his supposed spiritual role and his relationship with CWL got more distant. But in 1922 this changed. Krishnamurti arrived to Sydney in April to attend the Australian National Convention. There, he saw again CWL after about ten years. He wrote in a letter to Lady Emily: C.W.L. was "just the same", and added: "He is much whiter in hair, just as jovial & beaming with happiness. He was very glad to see us. He took my arm & held on to it & introduced me to all with a 'voilà' in his tone. I was very glad to see him too."[13]

During one of the meetings at the Convention an argument broke out concerning Leadbeater. J. Krishnamurti, who was present, declared that he knew Leadbeater better than most of those present, and that he could speak with some authority. As he reported later, he then declared that CWL "was one of the purest and one of the greatest men I had ever met. His clairvoyance may be doubted but not his purity."[14]

After Krishnamurti left Australia he began to meditate and regain his touch with the Masters, as a result of which he had a life-altering experience. After this he wrote to CWL:

I began consciously and deliberately to destroy the wrong accumulations of the past years since I had the misfortune of leaving you. Here let me acknowledge with shame that my feelings towards you were not what they should have been. Now, they are wholly different, I think I love and respect you as mighty few people do. My love for you when we first met at Adyar has returned bringing with it the love from the past. Please don't think that I am writing mere platitudes and worn out phrases. They are not and you, my dearest brother, know me, in fact better than myself. I wish, with all my heart, that I could see you now.[15]

Liberal Catholic Church

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

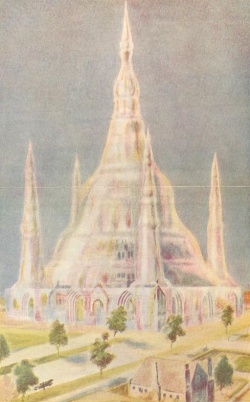

Leadbeater’s clairvoyant abilities shaped the development of the LCC. In 1920 he published The Science of the Sacraments, which described the astral forms that he saw when the Christian sacraments were performed. He found the Eucharist, or mass, to be particularly powerful. “It is a plan,” he wrote, “for helping on the evolution of the world by the frequent outpouring of floods of spiritual force.” When properly enacted, he said, the ceremony created an astral “thought-edifice” that can take on any number of variations, although it is usually based on a foursquare ground plan surmounted with a dome. To create as powerful a vehicle as possible, the celebrant needs to perform the Eucharist correctly and with intention (as opposed to rote mechanical enactment). The Catholic and Anglican rites of Leadbeater’s day were, he said, defective, so he and Wedgwood recast them. “We set to work to eliminate the many features which from our point of view disfigure and weaken the older liturgies,” James Ingall Wedgwood later wrote. “References to fear of God, to His wrath and to everlasting damnation were taken out, also the constant insistence on the sinfulness and worthlessness of man.” The resulting liturgy was published in 1919.

Years at The Manor

Return to Adyar

In 1929, Annie Besant wrote:

My Brother Leadbeater, after nearly 16 years' residence in Australia, has returned to Adyar to make his home here as of yore. For several years he has been living in Australia for nine months and making a three months' trip to Adyar. Now he retires to reverse that process. I am happy to have him with me again, for he is always a tower of strength and a fount of wisdom.[16]

Writings

Mr. Leadbeater wrote an extensive body of work, which is listed in Leadbeater writings. Often he collaborated with Annie Besant in writing about esoteric subjects. Young people such as Basil Hodgson-Smith and Fritz Kunz assisted with his massive correspondence, and Ernest Wood helped to compile some of the books.

Later years

He passed away on March 1, 1934 in Perth, Western Australia.

Honors and awards

Ananda College in Colombo, Sri Lanka awards the C. W. Leadbeater Challenge Trophy in honor of the first principal of the school.

The large 3-story residential building for visitors at Adyar is called Leadbeater Chambers. It was the first concrete building of its size in India, and the cornerstone was laid March 17, 1910 by Annie Besant.

Numerous Theosophical lodges have been named after Mr. Leadbeater. In the United States, there were Leadbeater Lodges in Chicago, Houston, New York City, and Jacksonville, Florida.[17]

Additional resources

Articles and pamphlets

- An Appreciation of C. W. Leadbeater by Geoffrey Hodson

- C. W. Leadbeater - A Great Occultist Compiled by Sandra Hodson and Mathias J. van Thiel

- C.W. Leadbeater in Retrospect By Hugh Shearman

Websites

- CWL World is a rich source of information, including documents and photographs.

- Articles by and about C.W. Leadbeater at Katinkahesselink.net

Audio

- To Those Who Mourn by C. W. Leadbeater

- Occult Commentaries by C. W. Leadbeater, G. S. Arundale & C. Jinarajadasa

Video

- "C W Leadbeater, Annie Besant, Krishnamurti - Theosophy UK". Footage of Annie Besant, C. W. Leadbeater, and J. Krishnamurti in mid-1920s, found in the archives of The International Theosophical Centre, Naarden, Netherlands. Available from Theosophy World Resource Centre.

Notes

- ↑ England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975.

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The "K. H." Letters to C. W. Leadbeater (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 53.

- ↑ James W. Matley "C. W. Leadbeater at Bramshott Parish," Appendix I of C. Jinarājadāsa, The "K. H." Letters to C. W. Leadbeater (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 105.

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The "K. H." Letters to C. W. Leadbeater (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 12.

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The "K. H." Letters to C. W. Leadbeater (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 14.

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The "K. H." Letters to C. W. Leadbeater (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 52.

- ↑ C. Jinarājadāsa, "Administration of Adyar Headquarters," The American Theosophist 36.5 (April, 1947), 73-75, 82.

- ↑ "General Secretaries". The Theosophical Year Book, 1938. (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1938), 152.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. IX (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 108.

- ↑ Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 21.

- ↑ «Naranian vs. Besant», lettera scritta da Annie Besant al Times, 2 giugno 1913, p.7.

- ↑ Kersey, John. 'Arnold Harris Mathew and the Old Catholic Movement in England 1908-52. p.199.

- ↑ Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 140.

- ↑ Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 143.

- ↑ Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 160.

- ↑ General Report of the Theosophical Society, 1929, page 21-22.

- ↑ National Secretary records. Theosophical Society in America.