Education and the Theosophical Movement

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Education has long been a focus of attention in many branches of the international Theosophical Movement.

Educational initiatives of the early Theosophical Society

Buddhist schools

The earliest involvement of the TS with education was in 1886, when the Society's president, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott began establishing schools in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), working with Sri Sumangala Thero. At that time, English missionaries dominated the educational options on that island. Buddhism was severely repressed, and many poor children had no access to schools. Olcott worked with local Buddhists to build schools, and brought in American, British, and Australian Theosophists to help organize them. He left a legacy of about 200 Buddhist schools in Ceylon, where he is a national hero. These schools were grounded in the local language, religion, and culture rather than trying to dispense Theosophy. Olcott was aiming to provide a service, not to proselytize. These are some of the most prominent schools that are still in operation:

- Ananda College was founded on November 1, 1886 in the capitol city of Colombo. In over 130 years of operation, the school has nurtured generations of leaders for Sri Lanka, with with 8,000 boys in 13 grades. It was named after a chief disciple of Gautama Buddha.

- Mahinda College in Galle is another boys' school that has been hugely successful for over 100 years.

- Musaeus College is a girls' school, founded in 1891 in Colombo by Marie Musaeus-Higgins.

Panchama schools

Colonel Olcott was also concerned about the outcastes in India known as panchamas, dalits, harijans, or paraiyars (pariahs). Olcott established 5 schools in South India. Initially staff members were Westerners, because Hindu teachers considered the students to be untouchable. Several of the schools were taken over by the government. The Olcott Memorial High School, established in 1894 as the Olcott Harijan Free School, continues serving children at the international headquarters in Adyar.

Hindu schools

Olcott establishing many Hindu schools in India, joined by many American and British Theosophists in parallel with his efforts in Ceylon. After he died in 1906, Annie Besant, his successor as president, carried on this work. She was very active in the Indian independence movement, and saw education as a high priority for creating generations of Indians who could bring their country into full equality with other nations in the modern world. She wrote:

The great aim of our education is to bring out of the child who comes into our hands every faculty that he brings with him, and then to try to win that child to turn all his abilities, his powers, his capacities, to the helping and serving of the community of which he is a part. [Annie Besant]

Mrs. Besant founded Central Hindu College in Benares (Varanasi) in 1898, along with its associated schools for boys and girls, and headed that initiative for 16 years.

Educational approach of early Theosophist-supported schools

These early school generally followed this approach:

- Native religious traditions were preserved or restored.

- Education was facilitated for girls and lower castes as well as boys.

- All religions, castes, and cultures were treated with respect.

- Native-born teachers taught religion, language, and arts suitable to the local population, while

- Western teachers offered modern educational methods, and taught sciences and business practices.

- Nationalism was encouraged, but along peaceful lines.

Educational initiatives of TS, Adyar

Theosophical Educational Trust

Society for the Promotion of National Education

The Society for the Promotion of National Education (SPNE) was an organization established in 1916 in India to support the development of schools based in Indian languages, religions, and customs. on December 27, 1916, the Theosophical Educational Trust, at its annual meeting, "resolved to make a present to the Society of its colleges and schools as far as possible." TS President Annie Besant was given authority to determine when and how the educational institutions should be transferred to the governance of the Society.

Staff and members of the Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Madras (now Chennai), India were heavily engaged in every aspect of SPNE's operation, although the two organizations were not legally connected. The participants were motivated by the desire to serve the Indian people and to prepare India to prepare for independence.

In 1924, the SPNE closed, and schools were merged back into the Theosophical Educational Trust.

Theosophical Fraternity in Education

Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa wrote a brief account of an English organization, the Theosophical Fraternity in Education.

There is to-day a great movement called the New Education Fellowship. It has spread to most of the countries in Europe, and also to North America, and nearly all distinguished leaders of education are among its principal officers, or on its committees. It publishes a review in three languages. It has held its congresses in the principal capitals of Europe, and its two last congresses were in South Africa and Australia. But this powerful movement for the ideals of New Education began with a band of Theosophists in England, who created the "Theosophical Fraternity in Education." A few rich Theosophists then poured thousands of pounds into experimental schools in connection with this work of the Fraternity. To-day, in India, the Theosophists have New Education Schools in several places; there is a school in Australia, another in New Zealand. In fact, one of the first results of our study of Theosophy is to understand the child from a new standpoint.[1]

The New Education Fellowship was an international organization dedicated to the ideals of progressive education. It was established in 1921 by Theosophist Beatrice Ensor, founder of a progressive school in Letchworth, England, along with several colleagues. The fellowship spread its philosophy through such journals as "The New Era" (now "The New Era in Education") in England and Progressive Education in the United States.[2] It is now known as the World Education Fellowship.

In the United States, the School of the Open Gate was affiliated with the Fraternity.

Raja Yoga education

Rudolf Steiner and Waldorf education

Educational approach

These are some of the elements of Waldorf education:

- Imaginative play is the work of young children.

- Reality is gradually introduced during the early years.

- Toys are objects made of natural materials designed to stimulate imagination, such as lengths of silk, wooden blocks, and plain dolls.

- The curriculum is concerned with developmental stages, unfolding consciousness, and age-appropriateness.

- Storytelling and fantasy are used to convey concepts.

- The atmosphere is one of beauty and harmony.

- Early cooperative activities foster social development.

- Emphasis is placed on the rhythms of the days and seasons.

- Children are engaged in a spiritual journey learning the inner realities of the physical world.

Montessori education

Dr. Maria Montessori was already well-established as an educator when she first met Annie Besant, president of the Theosophical Society, Adyar. Theosophists were very interested in Montessori education, and used its principles in a class at National Hindu Girls’ School in Madras, under the supervision of the Society for the Promotion of National Education. When World War II made Dr. Montessori's life in Italy too dangerous, TS president George S. Arundale invited her to reside at the Adyar headqarters of the TS in Madras (now Chennai), India. She and her son Mario used Adyar as their base of operations for ten years, conducting teacher training all over South Asia.

Educational approach

These are some elements of Montessori's educational approach:

- Fantasy is postponed until the child is grounded in reality.

- Tasks and activities are reality oriented.

- The intellect or "absorbent mind" is engaged early.

- Children are free to choose their own activities.

- Manipulative materials are designed to be aesthetically pleasing, and to support very specific educational goals.

- The atmosphere is calm and productive.

- Teacher is a facilitator of independent learning.

- Socialization begins with respecting the space of others.

- Older children voluntarily assist each other in learning.

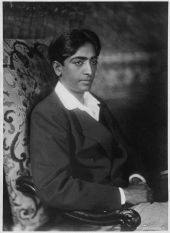

Krishnamurti education

As a young man in 1917, Jiddu Krishnamurti described "the life of an ideal school where love rules and inspires, where the students grow into noble adolescents under the fostering care of teachers who feel the greatness of their vocation."[3]

Krishnamurti schools

Krishnamurti founded several schools.

- Rajghat Besant School, built in Varanasi, India in 1934.

- Brockwood Park School in Hampshire, England was established in 1969.

- Oak Grove School in Ojai, California, built in 1975.

- Rishi Valley Education Center.

- "The School" at Damodar Gardens in Chennai.

- Haridvanam in Bangalore.

- Sahyadri School in Pune.

- Pathashaala in Chennai.

He said, "The purpose, the aim and drive of these schools is ... to create the right climate so that the child may develop fully as a complete human being. This means giving him the opportunity to flower in goodness so that he is rightly related to people, things and ideas, to the whole of life."

During the 1940s he worked with Aldous Huxley, Robert Logan, the Rajagopals, and Dr. Guido Ferrando to develop the Happy Valley School on land purchased in 1926 by Annie Besant. This independent school does not necessarily follow the same educational approach as the others.

Educational approach

These are some principles applied in Krishnamurti schools:

- School focus is on the development of the whole human being.

- Students learn to observe the world and act in the world without conditioning or self-centeredness.

- The school tries to establish an environment in which this kind of education and self-development can take place.

- Faculty work together to develop themselves as human beings who are capable of maintaining the educational environment.

- There is no fixed curriculum or method.

Theosophical schools

Theosophical schools have existed all over the world, for various lengths of time. Communities have come together to create special schools in Australia and New Zealand, in England, The Netherlands, Poland, Java (Indonesia), and The Philippines. There have been several attempts at establishing Theosophical universities, and huge energy has always been put into adult education. In many places, Theosophical lodges have conducted regular classes in Theosophy comparable to Christian Sunday schools. Teacher training programs were established in several countries, notably India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Java (now Indonesia), and The Philippines.

Educational approach

Theosophical schools tend to be tailored to local populations, offering arts, crafts, and languages that are culturally appropriate. Activities of daily life are understood to be suffused with spiritual meaning. Self-awareness, meditation, yoga, and spiritual forms of the arts are usually taught.

The concepts central to Theosophy are subtly emphasized, such as:

- Unity of all life in a universe filled with energy and consciousness

- Humans as energetic beings with a complex constitution

- Spiritual evolution

- Cyclicity of time

- Interconnections of religion, philosophy, science, arts

- Freedom of thought and belief

- Responsibility for own spiritual development.

School initiatives

- Arjuna schools in Java

- Morven Garden School in Sydney, Australia

Recent developments in education

Golden Link Schools

Adyar Theosophical Academy

The Adyar Theosophical Academy was established in 2019 in Besant Gardens at the Adyar headquarters of the Theosophical Society during the administration of Tim Boyd. The school uses the Golden Link College program of transformative education developed in The Philippines by Vic Hao Chin.

Additional resources

Articles

- Education and Theosophy at Theosopedia

- Education in the Light of Theosophy by Annie Besant

- Notes on Theosophy and Education by Bertram Keightley

- The Goal of Theosophical Education compiled by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Theosophical Education and the Golden Link College by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Readings on Theosophical Education compiled by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

Books

- Theosophical Education Chapter II in Thesis Dr Annie Besant and her contributions to society and politics 1893-1933 by Anthony Chaganti (See Table of contents)

- On Education by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Education as Service by J. Krishnamurti

Websites

Notes

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The New Humanity of Intuition (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1947), 136-137.

- ↑ New Education Fellowship at The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (March 18, 2024)]

- ↑ Jiddu Krishnamurti, Education as Service, 1917. Mentioned by Mary Lutyens in Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 6.