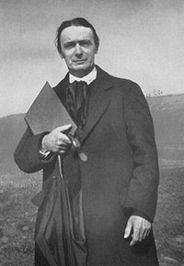

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (Born February 27 or 25, 1861 in Kraljevec, Austro-Hungary, today Croatia; died March 30, 1925 in Dornach, Switzerland) was an Austrian philosopher, mystic, author, natural scientist, scholar and social reformer. He founded anthroposophy, an esoteric spiritual movement with roots in German idealist philosophy, Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, and Gnosticism. His teachings exerted an influence in various areas of life including education (Waldorf schools), art (eurhythmy), architecture (anthroposophical architecture), medicine (anthroposophical medicine), and agriculture (biodynamic farming). With his ideas he laid the groundwork for today’s revolutions in alternative education, holistic health and organic foods.

Early life

Rudolf Steiner was born in Kraljevac, which was then in the dual monarchy Austro-Hungary, a stranger in a strange land, into a society made up of a rich mix of different ethnic groups, at the end of an old era and the birth of a new one. This experience colored both his childhood and youth. [1]; He was the son of Franziska Steiner (1834 – 1918), with whom he always had a loving relationship, and Johann Steiner (1829 – 1910), a minor railway official who thought of himself as a “free spirit”; both parents were from Lower Austria. [2][3]He had a younger sister named Leopoldine (1864 – 1927) who worked as a seamstress and lived with her parents until their death and Gustav (1866-1941), who was born deaf and was dependent on outside help all his life.[4]

Even in his young years Rudolf Steiner moved a lot. When he was 18 months old, the family moved to Mödling, six months later to Pottschach, a small, sleepy village in Lower Austria, in 1869 to Neudörfl, a small Hungarian village near the border of Lower Austria, where they stayed for ten years. He attended the village schools and then the secondary school in Wiener Neustadt. [5]

Steiner showed an early interest in natural sciences and enrolled in 1879 at the Technical University in Vienna to study biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics. Along with his studies at the institute he attended lectures at the University of Vienna, where he heard, among others, the philosopher Franz Brentano and Karl Julius Schröer, whose lectures about German literature held Steiner spellbound. [6]. He also participated actively in the rich cultural life of Vienna.

Professor Karl Julius Schröer, whose lectures Steiner attended, was a famous Goethe scholar. He befriended the young Steiner and arranged for him to edit the scientific works of Goethe for a new complete edition. Later Steiner was invited to Weimar, to the famous Goethe archive, where he remained for seven years, working further on the scientific writings, as well as collaborating in a complete edition of Schopenhauer. The place was a famous center, visited by the leading lights of Central European culture, and Steiner knew many of the major figures of the artistic and cultural life of his time. [7] Because he moved to Weimar he withdrew from the Institute of Technology in Vienna without graduating but got his doctorate in philosophy in Rostock in 1891 for his dissertation discussing Fichte’s concept of the ego. [8]

Already in his youth he was aware of his mission and accepted his calling without hesitation. At the age of fourteen he discovered Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason and immersed himself in this book despite difficult external circumstances. He also learned bookbinding during that time, as well as stenography and had plenty of opportunities for practical work, especially in the garden. At the same time, he got interested in literature, philosophy, psychology and history, and he started to tutor. His experience as an altar boy opened up a lot of questions for him as well. And already in his youth he was pondering about reincarnation. “During that same time, through spiritual perception I gained a definite understanding of repeated earthly life. I certainly had this insight before then, but in broader outlines, not as clearly defined impression. I did not construct theories about things such as repeated earthly lives; I accepted it as self-evident when I encountered it in literature and otherwise.” [9]

In 1894 he published “Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path: A Philosophy of Freedom”. Then, as the end of the century approached, he left Weimar to edit the avant-garde literary magazine, Magazin für Literatur in Berlin, a city with several radical groups and movements at that time, where he met playwrights and poets. There he was asked to lecture at the Berlin Workers' Training School, sponsored by the trade unions and social democrats. Most of the teaching was Marxist, but he insisted on a free hand. He taught courses on history and natural science, and practical exercises in public speaking. His lectures had such great appeal that he was invited to give a festival address to 7,000 printers at the Berlin circus stadium on the occasion of the Gutenberg jubilee. But in the end his refusal to toe any party line did not endear him to the political activists, and soon after the turn of the century, he was forced to drop this work.[10][11]

Spiritual Development

Around 1868, still in Pottschach, Rudolf Steiner had a mysterious experience that had a profound influence on him. It had to do with the suicide of an aunt. He gave two different accounts of this episode.

“My parents had no notice of her death. I sat in the waiting room of the train station and saw a vision of what had happened. I tried to tell my parents. They replied, “Don’t be a silly boy”. Some days later, I saw my father become pensive after receiving a letter. Later, in my absence he spoke with my mother, who cried for days thereafter. I heard the details of my aunt’s death only years later.”

When Rudolf Steiner talked about his childhood and youth in a lecture in Berlin on February 4, 1913, he described the experience in more detail. He mentioned that suddenly the door opened and a woman with a strong family resemblance entered, walked to the middle of the waiting room, gesticulating and uttering words to the effect of: “Try to do all you can do for me, now and later!” She continued to linger for a moment, still gesticulating in a heartrending way, then went towards the hearth and disappeared in it.

Rudolf Steiner spoke at a later point about the intensity of the desperate gestures and the deep impact they made on him. This “occult-experience” was crucial to Steiner’s further development. He also realized then that it was not possible to speak with most people about inner experiences or questions. [12][13][14]

Therefore it was difficult for Steiner to share this experience or his philosophical ideas with any of his friends because they were met with a lot of resistance. Even though during this time people were fascinated with séances, materializations and messages from the dead, Steiner was repulsed by spiritualism. He considered spiritualists “more materialist than the materialists” because, they wanted to prove the existence of the spiritual world by grabbing hold of some physical evidence of it. This was for Steiner like black magic.[15]

So it must have been a relief for Steiner when at the age of eighteen he made the acquaintance of an individual, an herb-gatherer, who felt as at home in the realm of the supersensible as he did himself. He called him a “simple man of the people.” Felix Koguzki, who was then 46 years old, gathered herbs to sell to pharmacists in Vienna. [16]

Koguzki tried to explain each plant out of its essence, out of its esoteric background, led him to places where rare plants grew and gave Steiner the impression that he was simply the mouthpiece for spirituality from the hidden worlds who conveyed to him the secrets of nature. This herbalist was also the one who, either knowingly or unknowingly, prepared the meeting with Steiner's true esoteric teacher, who Steiner, using a theosophical term, called the Master. Steiner was always reticent concerning the meeting with this spiritual teacher and never mentioned his given name. He only said that in this outer life he was as “unremarkable” as was Felix Koguzki. In his own brief account, Steiner emphasized that since his own spiritual experience allowed him to move independently in the spiritual world, his teacher focused on the regular, systematic aspects of which one must be aware of in the spiritual world as well as on the proper orientation in the spiritual world. From that one can assume that Steiner did participate in a path of esoteric learning. [17]

Theosophical Society

While still living in Vienna, and during the time, when Rudolf Steiner's spiritual perception of repeated earthly lives was becoming increasingly defined, he was introduced to Theosophy. A friend had sent him Sinnett's Esoteric Buddhism but he was not particularly impressed and glad that he had attained perceptions from his own soul life before reading it.[18] At a later point, but still in Vienna, he met frequently with a group of theosophists in the home of Marie Lang, and found those hours extremely valuable. Franz Hartmann had brought his theosophy into this group but Steiner felt, that the architects, writers and others in this group could hardly be interested in the theosophy of Dr. Hartmann and emphasized in his autobiography that he would not have become interested because he felt that Hartman's whole attitude to the spiritual world was in direct opposition of his own.[19]

After Weimar and then living in Berlin, Steiner’s urge to become publicly active on behalf of spiritual knowledge became stronger and stronger: “On the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Goethe’s birth (August 28, 1898), I intended to publicize the esoteric knowledge living in me.” [20] He published an article in the literary magazine on Goethe’s alchemical fairy tale The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily and a young member of the Berlin lodge of the Theosophical Society, Fritz Seiler, was impressed. Through him, the Count and Countess Brockdorff invited him to give lecture at one of their weekly meetings. He gave his first one on September 22, 1900 and when invited back he finally allowed himself to speak publicly about his spiritual experiences.[21][22]

In 1902 he became the head of the “German Theosophical Society” and read not only H. P. Blavatsky and Annie Besant, but also formed for himself a picture of the Theosophical Society. Even though he had issues with some parts of the Society and found only among the English theosophists inner meaning that arose from Blavatsky, [23] he defended Blavatsky’s work against critics: “She combined what she attained in this way with revelations that arose within herself. She was an individual with peculiar atavistic powers. Spirit worked through her in a dreamlike state of consciousness, just as in ancient times it had acted through leaders of the Mysteries – unlike our modern consciousness, which is illuminated by the consciousness soul. Thus in “Blavatsky the human being” something recurred that was innate within the Mysteries during primordial times.” [24]

At the time the German Section of the Theosophical Society was established, Steiner also felt it necessary to have his own periodical and he began, together with Maria Sivers, not only a Theosophist who managed the Theosophical Society with him, but also a close friend who he eventually married, the monthly magazine Luzifer, which later merged with the journal Gnosis and appeared as Lucifer-Gnosis. In his opinion anthroposophy had developed from his contributions to that periodical and consequently the material became the foundation for anthroposphic activity. [25]

In 1902 he published the book Christianity as a Mystical Fact. Additional works after that were published in the Philosophical-Anthroposophical Publishing Company, which was made possible through Marie von Sivers’. After a booklet that contained notes from lectures he had given at the Berlin Independent College, he publishedIntuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path: A Philosophy of Freedom and other writings. [26]

The years when he was head of the Theosophical Society were not only very productive but Steiner also experienced the realities and beings that approached him from the spirit world and developed specific insights from these experiences. [27]Initially, Steiner had not planned “to develop higher worlds and evolution. His goal was to help students of the spirit find the path of development.”[28] But then, in the fall of 1903, he began to present theosophy systematically in lectures for members and to work on the book with the title Theosophy, which was published in 1903. The intention of Theosophy for Steiner was not to bring a new truth but to provide instructions to awaken one’s spirit. [29]In 1909 he published another important book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, a handbook on developing spiritual perception, which originated in a Rosicrucian inspiration. [30] [31]During that time he gave many lectures and the notes from then and similar accounts from later represent a big part of Collected Works of Rudolf Steiner.

In his autobiography Steiner addresses his acceptance into the Esoteric School of the Theosophical Society, which dated back to H.P. Blavatsky, in which she communicated matters she did not wish to speak of to the general society. He writes that he had to keep informed of everything taking place within the society and that was the reason he became a member of the Esoteric School. But he emphasized that he did not receive any special knowledge because in his opinion the only real substance in that school came from H.P. Blavatsky, and that could be obtained in print. [32] Annie Besant appointed him to be the “arch-warden of the E.S. in Germany and the Austrian empire” on May 10, 1904, but even then Steiner already knew that there was a crisis looming in the T.S. that would affect him.”[33]

In the years leading up to World War I, Steiner viewed the Theosophical Society and with it the worldwide collaboration of the society as something that could work against the forces of war. His relationship to the leadership of the society at that time was still loyal. He also believed that living theosophy should be a center of spiritual life and came up with thoughts and indications for practical life. But he couldn’t find anybody who was truly interested in bringing theosophy to bear in such a way that its fruits could flow into civilization as a whole. During that time, he came up with symbolic rituals instead of becoming practically active in the social realm, which lead to some controversies over the years. [34]

Despite the controversies surrounding Annie Besant’s choice to take on the leadership of the Theosophical Society after Olcott’s death, Steiner supported electing her to be president but he separated his Esoteric School from the general Esoteric School because he considered his training as different. [35] Annie Besant did respect Steiner’s work, praised him in some of her articles but at the same time, the differences between C. W. Leadbeater and Besant on the one side and Steiner on the other side did not go unnoticed. Whereas the former saw Krishnamurti as the vehicle of the coming Maitreya, Steiner talked about a second coming of Christ, but called it the “etheric Christ”. Even though, we might never know if Krishnamurti was groomed as a rival to Steiner’s growing celebrity[36] Rudolf Steiner also respected Annie Besant: “Mrs. Besant had certain qualities that, to me, made her an interesting person. I recognized that she had a certain right to speak of the spirit world from her own experience. She certainly had an inner ability to get through to the spiritual world.” But in Steiner’s opinion, spiritual insight had to live within the conscious soul. He was convinced, that in the Middle Ages the ancient spiritual knowledge faded away when people gained a conscious soul, and that the task of spiritual knowledge is to bring the experience of ideas to the spiritual world in full clarity of mind and through the will to know. He felt that it was impossible to develop the correct relationship to his understanding on how to gain spiritual knowledge, and in his autobiography he gives this as one of the reasons for the break. He wrote that it was socially a pleasure to move in those circles, but that the member’s soul disposition toward spirit remained alien to him. [37] The break came when Steiner found out about The Order of the Star in the East and Steiner refused to allow the order to operate in Germany. That’s when the peaceful coexistence ended, and Dr. Rudolf Steiner was no longer a member of the Theosophical Society.[38]

Steiner led the German Section to a resolution, adopted on December 8, 1912, that membership in the Order of the Star in the East (OSE) was incompatible with membership in the Theosophical Society. Considering it a matter of “spiritual cleanliness,” the Section expelled OSE members.

Steiner’s expulsion of OSE members from the TS despite the official international TS policy of freedom of thought and of association, and his refusal to charter German TS lodges if the applicants were OSE members, were the main grounds on which Besant, on January 14, 1913 wrote to Steiner threatening to withdraw the charter of the German Section, and on which, on March 7, 1913, the General Council of the international TS officially withdrew the charter. In between those two events, Steiner’s new Anthroposophical-theosophical Society met first on February 3, 1913. Its founding membership consisted of members of the soon-to-be-dechartered German TS Section.[39]

In the end it would have come to the break one way or the other. Blavatsky believed that humankind was moving through a series of stages that would result in the creation of purely spiritual beings and that the key to advancement was found in the "ancient wisdom" of early cultures. When it came to Christ, the belief was that he was simply another teacher in a long line of mystics such as Buddha and Krishna and that Christianity was no better than other religions. Steiner believed that ancient mystics had paved the way for Christ's appearance on Earth and that Christianity had supplanted Eastern religions. Further, Steiner differentiated between Jesus and Christ. He designates Jesus as a higher spiritual student, a chela, who sacrificed his life to the incarnating Christ who bore the buddhi principle to the earth. In Theosophy, the buddhi principle forms one aspect of the human organization.[40]

In addition Steiner had concluded

- that the spirit world is real, not illusory;

- that the the only way to understand and learn from it is to observe closely as a scientist would observe the material world;

- that the only limits on such observation are the limits of our perceptive organs;

- that there must therefore exist special organs of spiritual perception which are simply atrophied in most individuals.[41]

Anthroposophical Society

Prior to his death Steiner summarized his leading thoughts and provided insight on his life's work. The first "leading thought" contains probably the best known definition of anthroposophy: "Anthroposophy is a path of knowledge, to guide the spiritual in the human being to the spiritual in the universe."[42]

Anthroposophy (derived from the Greek words “anthropos, “human”, and “sophia”, “wisdom”) is a philosophy that is concerned with all aspects of human life, spirit and humanity’s future evolution and wellbeing. It postulates the existence of an objective, intellectually comprehensible spiritual world that is accessible by direct experience through inner development. It is a path of knowledge, service, personal growth and social engagement. With Anthroposophy each individual spiritual seeker can develop a warm and will-filled means to overcome the alienation that seemed to be in Steiner’s view characteristic of Western modern consciousness. Steiner considered the purpose of the evolution of human consciousness, for which he regarded the incarnation of Christ as the central event, to be the attainment of human love and freedom. [43][44][45]The philosophy has roots in German idealism and German mysticism and was initially expressed in language drawn from Theosophy. [46]

The Anthroposophical Society was founded on December 28, 1912 in Cologne, Germany, with about 3000 members. There were many artistic activities such as summer festival weeks with performances of “mystery plays. The Society was re-founded in 1923 and Steiner established a School for Spiritual Science. As a spiritual basis for the refounded movement, Steiner wrote a “Foundation Stone Meditation” [47] which remains a central meditative expression of anthroposophical ideas. [48]

Anthroposophical ideas have been applied practically in many areas including the Waldorf and special education, biodynamic agriculture, beauty products and naturopathic medicines (Weleda, Wala Heilmittel), ethical banking (Triodos Bank N.V.), organizational development and the arts.

Today there are Anthroposophical Societies in 50 countries and smaller groups in an additional 50 countries. About 10,000 institutions around the world work on the basis of anthroposophy.[49]The Anthroposophical Society in America ended the year 2015 with 3,287 members [50] Anthroposophy Worldwide is the main international newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society.[51]

Waldorf education

Today Rudolf Steiner might be best known for the Waldorf education and special education. The former originated in a request from Emil Molt, director of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory, for a school to which his employees could send their children. Emil Molt sought to provide a new kind of education for the children — a comprehensive and highly cultural education that would help them to become creative and balanced individuals in the fullest sense. Steiner developed a complete curriculum and trained teachers within a year, and the school opened in 1919. Molt and other contemporaries related that they never had seen Steiner as joyful as at the celebration of the opening. The inauguration of a new pedagogical impulse was something that Steiner had striven toward for many years because he felt that education was a field where Anthroposophy could have a practical effect on the time.[52]

Waldorf pedagogy emphasizes the role of imagination in learning, striving to integrate holistically the intellectual, practical, and artistic development of students. Philosophy, music, dance, theater, writing, literature, legends and myths are not only read about and tested but also experienced. [53][54][55]

The Waldorf educational framework has been highly influential, especially in Europe, where many state-run Waldorf schools have been established. Over one thousand independent Waldorf schools and 2000 kindergartens have been established by local initiatives in at least 60 countries on six continents. Teacher training academies are found in numerous locations, and Waldorf curricula for home schooling are in wide use in the United States.

Curative education and special needs

When Steiner lived in Vienna, he tutored the children of the Specht family. Their son Otto, who suffered from a mental and physical disability, hydrocephalus, water on the brain, needed special attention. Otto had been given up as hopeless and had not yet mastered the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic at the age of ten. His vitality was low; he suffered from headaches and the slightest mental effort exhausted him. Steiner understood that he would first have to gain the boy's love and trust, a slow but rewarding task. In the end, Steiner acquired through the work with Otto his basic insights into the relation between the human body and the soul. Otto's confidence grew through the attention and care Steiner showed towards him and even his physical health improved. Otto went on to study medicine and became a doctor. This proved to Steiner, that physical health is determined by the inner, mental state. Steiner's success with Otto has to be recognized as of the most remarkable cases of curative education on record. The insights Steiner gained through this work was the basis for his work in Waldorf education and special-needs education, which became the foundation of the many Camphill schools that deal with students "in need of special care of the soul."[56] Over 640 homes, schools, and village communities for handicapped children and adults have been flourishing under this method.

Biodynamic farming

Biodynamic agriculture is a form of alternative agriculture, very similar to organic farming, but it includes various esoteric concepts. Rudolf Steiner developed this system based on his clairvoyant perceptions of subtle energies at work during the growth of plants. Biodynamic agriculture originated in a course of lectures at Koberwitz in 1924, held at the request of a group of farmers concerned about the destructive trend of “scientific” farming.[57]

Steiner himself did not use the term “biodynamic” but it does reflect his belief that farming and gardening should be practiced “biologically” and “dynamically”. This means that the soil that is used for gardening and farming should be seen as a living, organic system. It should also be remembered that the kernel of anthroposophy rests in Goethe’s ideas about the Urpflanze, the archetypal plant whose presence Goethe discovered through his practice of active imagination. Steiner told the farmers that certain natural preparations used in combination with compost and manure could help restore vitality to the depleted soil but that the preparation had to be subject to cosmic rhythms and the forces of the season. [58]

Goetheanum in Dornach

The Goetheanum is the world center for the anthrosophical movement. The building was designed by Rudolf Steiner and named after Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Steiner laid the cornerstone of the Goetheanum Building, which is located in Dornach, Switzerland, on September 20th 1920. [59]). It opened in 1920 and was destroyed by fire on New Year's Eve 1922/23. Only the great sculpture of “The Representative of Humanity” on which Steiner had been working in a neighborhood workshop with the English sculptress Edith Maryon survived the fire. [60] In 1924 Rudolf Steiner presented his model for the second Goetheanum, which is made of reinforced concrete. It was constructed from 1925 until 1928 and now serves as a center for the world-wide Anthroposophical Society and its School of Spiritual Science. Both buildings are based on an architectural concept in which each element, form and color bears an inner relation to the whole and the whole flows organically into its single elements in a process of metamorphosis. The second Goetheanum and its neighboring buildings were designed to harmonize with the local topography. The Goetheanum is surrounded ateliers, research buildings, an observatory, apartment houses, guest houses, restaurants and other structures in an extensive garden.

Approximately 300 people work on the campus and over 100 000 visitors come to the Goetheanum each year.[61]

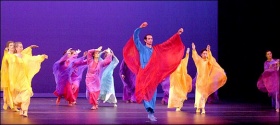

Eurythmy

Eurythmy stems from Greek roots meaning beautiful or harmonious rhythm. It is an expressive movement art originated by Rudolf Steiner together with Marie von Sivers. Steiner not only developed a new way of dancing but also a new art of etheric movement. Steiner developed eurythmy for three reasons: as a performance art, for therapeutic use, and for pedagogical use in schools. It is a way of making the inner qualities of speech and music visible and it is “spiritually restorative by forming and strengthening the performer’s subtle, etheric body, which surrounds and pervades the physical body.” [62] Steiner believed, that music and painting activate the astral body and that the human astral body “contains the actual element of music”. At the end of his life Steiner said that he wished he would have spent “more time working with the arts and that, for the West, the arts are the most effective way to spirit." [63]

The Threefold Social Movement

The Threefold Social Movement is a theory suggesting the progressive independence of society's economic, political and cultural institutions. It supports human rights and equality in political life, freedom in cultural life, and cooperation in economic life. Rudolf Steiner proposed the idea at the end of World War I. He was in Berlin at the end of that war and was able to follow the symptoms of inner decay. He had for years observed with concern German politics. He believed in the importance of positive statements in international politics. He formulated his thoughts in the summer of 1917 and placed individual freedom and the limitation of government power against the anticipated consequences of an approach based on ethnic self-determination that would lead to the repression of minorities. Besides the autonomy of the legal, educational and cultural spheres, the threefold approach put limits on what was to be decided democratically. Steiner, who never voted in an election, supported human rights and the well-being of workers, did not believe in democracy in the modern sense of the word. He was always concerned with individual freedom and looked upon any form of ruling power skeptically. Steiner had no desire to play a political role but saw the actions of German’s leaders as dangerous. He never seemed to mind talking to politicians to find support for the threefold social order even though he knew the conversations would lead nowhere. He turned his attention to other tasks after the “fatal” peace treaty was signed in March of 1918. [64]

Personal Life

Rudolf Steiner was less than forthcoming about his private life. He believed that “a person’s private life does not belong to the public”. [65]. Steiner’s relationships with women, at least as recounted in his autobiography, tended to be of the platonic type.

When he lived in Vienna he developed a strong bond with Pauline Specht, the mother of four boys he tutored. With her he could speak about spiritual experiences; she took an interest in his philosophical and scientific pursuits and they talked about problems of life. For a time, Steiner even felt it essential to discuss all his important decisions with her. Steiner admitted, when it was time for him to leave Vienna, separating from Frau Specht was one of the things that made this decision difficult. [66]

When he lived in Weimar he found a congenial home amid the family of Anna Eunicke. a widow. She offered Steiner an apartment with the understanding that he would help with the education of her five children, which he was glad to do. She was a decade older than Steiner but they developed soon an intimate friendship. “She watched over all his needs in the most devoted fashion”, according to Steiner. They were subsequently married on October 31, 1899 in Berlin where they had moved to. Anna Eunicke died on March 17, 1911 but had separated from Steiner a few years before her death. [67][68][69]

Marie von Sivers, his second wife, was a central character in his life story. She became a Theosophist in 1900 and attended one of Steiner’s lectures the same year. They met soon after and started working together running the German Section of the Theosophical Society which was founded in 1902 in Berlin. She also accompanied him that year when he made his first visit to London to attend the annual meeting of the European sections of the Theosophical Society. The same year they began the periodical Lucifer, later called Lucifer-Gnosis. They continued to work closely together. She was trained in recitation and elocution and made a study of purely artistic speaking. She gave introductory poetry recitals at Steiner's lectures and assisted him in the development of the four Mystery Dramas (1910–1913). With her help, Steiner conducted several speech and drama courses with the aim of raising these forms to the level of true art. They got married on December 24, 1914. She made a great contribution to the development of anthroposophy, particularly in her work on the renewal of the performing arts (eurythmy, speech and drama), and the editing and publishing of Rudolf Steiner's literary estate. [70][71][72]

After Rudolf Steiner's death Marie Steiner discovered his testament from February 19, 1907, which gave her legal right to act in his name. "Whatever she does shall be done in my name." [73]

Mrs. Marie Steiner-von Sivers died on December 27th 1948.

Ita Wegman, a doctor, is known as the co-founder of Anthroposophical Medicine and founded in 1921 the first anthroposophical medical clinic in Arlesheim, Switzerland, now known as the Ita Wegman Clinic. She also developed a special form of massage therapy, called rhythmical massage, and other therapeutic treatments. She met Rudolf Steiner in 1902 at the age of 26 and after conversations with him and Maria Steiner von Sivers she decided to study medicine. In 1917, after having opened an independent practice, she developed a cancer treatment using an extract of mistletoe following indications from Steiner. This first remedy, which she called Iscar, was later developed into Iscador and has become an approved cancer treatment in Germany and a number of other countries,[74]and is undergoing clinical trials in the U.S.A. [75]

After Rudolf Steiner had opened the Gotheanum in Dornach he asked Wegman to join the Executive Council. She also directed the Medical Section of the research center there. Steiner and Wegman wrote Extending Practical Medicine, which gave a theoretical basis to the new medicine they were developing. When most of this book was written Steiner was already terminally ill and Wegman cared for him. The two of them had a very close relationship and they seemed to have developed feelings for each other that are documented through letters. Steiner explained their relationship karmically. This led to fraught relationships with Maria Steiner von Sivers.

After Steiner’s death difficulties between Wegman and the rest of the Executive Council flared up and Wegman was asked to leave the Council; in addition, she and a number of supporters had their membership in the Anthroposophical Society itself withdrawn.

Ita Wegman died in Arlesheim in 1943, at the age of 67. [76]

Writings

An index to Rudolf Steiner's complete works is available online at Rudolf Steiner Web.

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists over 159 articles by Rudolf Steiner and 129 articles about him. Most are from his journal Anthroposophy or The Theosophist.

Online resources

- Rudolf Steiner Archiv (English-language version of web site) [1]

- Anthroposophical Society [2]

- AnthroWiki in German [3]

- Steiner, Rudolf in Theosophy World

- Rudolf Steiner Web by Daniel Hindes [4]

- The Goetheanum [5]

- Rudolf Steiner Archiv (German-language version of web site) [6]

- Works of Rudolf Steiner at Project Gutenberg [7]

- Works of Rudolf Steiner at Projekt Gutenberg in German [8]

- Works of or about Rudolf Steiner on the Internet [9]

- Rudolf Steiner by Heiner Ullrich [10]

- Rudolf Steiner by Carlin Romano [11]

- Rudolf Steiner's Blackboard Drawings - Berkley Art Museum [12]

- Rudolf Steiner by the Skeptic's Dictionary [13]

- Rudolf Steiner's Meditative Technique by Derek Cameron From Insult to Insight: Rudolf Steiner's Meditative Technique

- The Online Waldorf Library [14]

Notes

- ↑ Gary Lachman, Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2007), 3.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf, and Robert A. McDermott. The New Essential Steiner: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner for the 21st Century. Great Barrington: Lindisfarne, 2009, page 73

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Http://www.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 25 July 2016.

- ↑ “Rudolf Steiner.” AnthroWiki. N.p. n.d. http://anthrowiki.at/Rudolf_Steiner. Web 9 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 15ff

- ↑ Lachman, 39.

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Http://www.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 25 July 2016 .

- ↑ Robert A. McDermott, "Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy", in Faivre & Needleman, Modern Esoteric Spirituality, 288.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 94

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 245 ff

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Http://www.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Selg, Peter. Rudolf Steiner: Life and Work: Volume 1 (1860 – 189) Childhood, Youth and Study Years. Web. 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 7

- ↑ Rudolf Steiner, Autobiographischer Vortrag über die Kindheits- und Jugendjahre bis zur Weimarer Zeit, in: Beiträge zur Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe, Heft Nr. 83/84

- ↑ Lachman, 47.

- ↑ Lachman, 48.

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 43ff

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 94

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 107

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 254 ff

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 256

- ↑ Lachman, 125.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 269

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 276

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 274 ff

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 280

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 281

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 261

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 272 ff

- ↑ Lachman, 137.

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 299

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 275 ff

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 278 ff

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 288 ff

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 302 ff

- ↑ Lachman, 163.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 278 ff

- ↑ Lachman, 170.

- ↑ S. Lloyd Williams, “Did J. Krishnamurti Write ‘’At the Feet of the Master?”, ‘’Theosophical History’’ 14-3 and 4 (Double issue, July-October, 2010), 25.

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 332

- ↑ Washington, P.Madam Blavatsky's Baboon>Schocken Books Inc., New York, 1993. p. 148

- ↑ Lachman, 226.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf, and Robert A. McDermott. The New Essential Steiner: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner for the 21st Century. Great Barrington: Lindisfarne, 2009, page 3ff

- ↑ The Anthroposophical Society in America.N.p.n.d. http://www.anthroposophy.org/about/. Web 10 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Anthroposophie. AnthroWiki. N.p.n.d. http://anthrowiki.at/Anthroposophie. Web 11 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Christian Clement (ed.), Rudolf Steiner: Schriften über Mystik, Mysterienwesen und Religionsgeschichte. Frommann-holzboog Verlag, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt, 2013, page. xlii

- ↑ Rudolf Steiner. The Foundation Stone Meditation. N.d. http://southerncrossreview.org/43/foundation-stone.htm. Web Aug. 2016

- ↑ Robin Schmidt. History of the Anthroposophical Society. Goetheanum. N.d. https://www.goetheanum.org/Overview.481.0.html?&L=1. Web 11 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Robin Schmidt. History of the Anthroposophical Society. Gotheanum. N.d. http://www.goetheanum.org/Pluralization-and-questions-of-identity-1990-until-today.124.0.html?&L=1. Web 11 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Annual Report for 2015. http://www.anthroposophy.org/fileadmin/development/2015AnnualReportOnline.pdf

- ↑ Anthrosophy Worldwide. Gotheanum. N.d. https://www.goetheanum.org/Newsletter.aw.0.html?&L=1. Web 11 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 506

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. Accessed 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Directory of Waldorf and Rudolf Steiner Schools, Kindergarten and Teacher Training Courses. N.P. http://www.freunde-waldorf.de/fileadmin/user_upload/images/Waldorf_World_List/Waldorf_World_List.pdf. Web 12 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Waldorf Education: An introduction. Waldorf Education. N.d. https://waldorfeducation.org/waldorf_education. Web 12 Aug. 2016

- ↑ Lachman, 57.

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Http://www.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 25 July 2016

- ↑ Lachman, 218.

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 307

- ↑ Davy, John. "Rudolf Steiner: A Sketch of His Life and Work." Http://www.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 28 Oct. 2014. Web. 19 Sept. 2016

- ↑ The Building. Goetheanum. N.d. https://www.goetheanum.org/en/anthroposophyrudolf-steiner/the-goetheanum-building/ Web 19 Sept. 2016

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf, and Robert A. McDermott. The New Essential Steiner: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner for the 21st Century. Great Barrington: Lindisfarne, 2009, page 49 ff

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf, and Robert A. McDermott. The New Essential Steiner: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner for the 21st Century. Great Barrington: Lindisfarne, 2009, page 50 ff

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, chapter 37

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 244

- ↑ Lachman, 59.

- ↑ Lachman, 88.

- ↑ Barnes, Henry. A Life for the Spirit: Rudolf Steiner in the Crosscurrents of Our Time. Steiner Books, Vista Series in 1997. Page 55

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. The Story of My Life. http://www.southerncrossreview.org/55/steiner-life20.htm. Web. 19 Sept. 2016

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. The Story of My Life. http://www.southerncrossreview.org/55/steiner-life20.htm. Web. 19 Sept. 2016

- ↑ Works of Marie Steiner. http://wn.rsarchive.org/RelAuthors/SteinerM. Rudolf Steiner Archive & E.Lib, 19 Sept. 2016

- ↑ Steiner, Rudolf. Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life, 1861-1907. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophie, 1999, page 274 ff

- ↑ Lindenberg, Christoph. Rudolf Steiner: A Biography. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner, 2012, page 760

- ↑ Kienle, Kiene & Albonico, Anthroposophic Medicine, Schattauer, Chapters 3 and 6

- ↑ National Cancer Institute, n.d. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/mistletoe-pdq#link/_7. Web 20 Nov. 2016

- ↑ Zander, Anthroposophie in Deutschland. 2007, p 1531ff