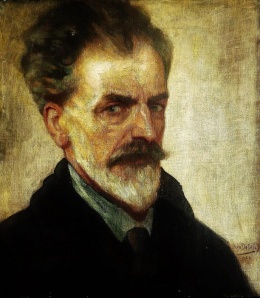

Jean Delville

Jean Delville (1867–1953) was a Belgian symbolist painter, author, and teacher. He was the first General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in Belgium, from 1911-1913.

Early years

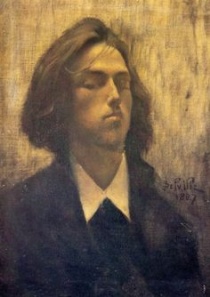

Jean Delville was born in Louvain, Belgium on January 19, 1867. As a boy he was not interested in school, so at age 15 his parents allowed him to enroll in the School of Arts at Brussels. After two years of study, he was awarded prizes for composition, painting and drawing from life. [1][2] During his first years as an artist, he lived in poverty at St. Gilles in Brussels. By the mid-1890s, he had married and begun a family. Winning the Prix de Rome in 1895 greatly improved his fortunes and refined his style, but for many years he had to supplement his irregular income from painting with teaching positions.

During the tumult of the First World War, the Delville family lived in London. The artist turned his attention to Belgian expatriates and refugees, and sold a volume called Belgian Art in Exile to raise money for charities. He continued painting, with symbolic warfare as a theme. His monumental work Les Forces, 5 metres by 8 metres in size, depicts two enormous spiritual armies in conflict. It was completed in 1924 and is now displayed in the Palais de Justice in Paris.

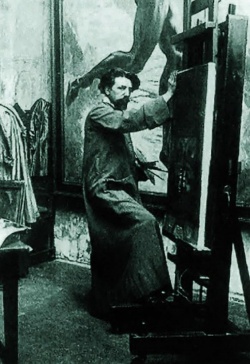

Artistic career

Delville created works of art with great technical skill and originality. He tried to find a style apart from the naturalistic aestheticism and the materialistic realism of the day; his work is idealistic.

First exhibition

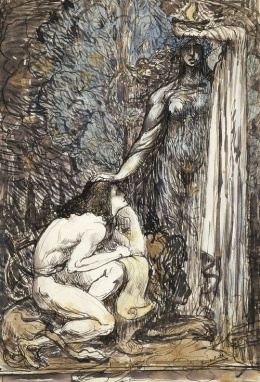

Deville's first publicly exhibited painting was a large canvas called Le Cycle Passionel of a nude woman. He was just eighteen, and the year was 1885.

Young Delville depicted the whirlwind of sensual desire and lewdness which Dante had described in the Inferno. The picture caught the attention of the art-critics by its disclosure of a new genius of the brush who possessed not only phenomenal skill but great power of conception. It also struck the note of exalted seriousness which has characterised all his work... [his pictures], while classical in their structural and technical perfection, made no concession to softness or sentimentality and always made the affirmation of power and chastity.[3]

His first major exhibitions were at L'Essor exhibition society, where his works drew a great deal of attention.

Exhibitions at Salons de la Rose+Croix

Sâr Joséphin Péladan (1858 -1918) created the Order of the Rose+Cross of the Temple and the Grail in Paris, 1884. Delville met Péladan in in 1887 or 1888, and adopted Rosicrucian ideas. "Between 1892 and 1895, he exhibited paintings in the Sâr’s Paris Salons of the Rose+Cross. After 1895, Delville dissociated himself from the Sâr, though he remained true to many of the latter’s esoteric concepts."[4]

Salon d'Art Idéalist

In 1896, Delville founded the Salon d'Art Idéalist, "in imitation of the Salons de la Rose+Croix."[5] Members included Léon Frédéric, Auguste Levêque, Albert Ciamberlani, Constant Montald, Emile Motte, Victor Rousseau, Armand Point and Alexandre Séon among the members. These artists wanted art to go beyond realism and materialism into the concepts of the ideal; aesthetic principles from freemasonry, Neoplatonism, Rosicrucianism, and Theosophy predominated. The salon existed for only about three years.

Pour L'Art, 1892-1895

Delville established an exhibition society in Brussels called Pour L'Art, with the first exhibition taking place in November 1892. Joséphin Péladan came from Paris to lecture there, and artists with international reputations brought their work to Brussels to exhibit.

Artistic style

The well-trained Delville worked in many artistic media - oil, tempura, chalk, pencil, charcoal, and even mosaic. He experimented with many color schemes and styles, but always looking at the inner reality, the central idea, of what he was painting. He wrote in La Mission de l'Art of the expressiveness of idealist art: "Before works of genius the human consciousness receives mental and spiritual vibrations, which are generated by the force of the idea reflected."[6]

As a mystic strongly influenced by Neoplatonism, Delville believed that visible reality was only a symbol, and that humans exist in three planes: the physical (the realm of facts), the astral (or spiritual world, the realm of laws), and the divine (the realm of causes). These higher planes of existence were the only significant ones. Materialism was a trap, and the soul had to guard against being trapped by its snares... Reincarnation was to provide the path to the highest level for those who perfected their will and spirit through initiation and magic. He reconciled his interest in the occult with Christianity by considering Catholicism to be in harmony with magical laws: the external forms of devotion concealed occult truths. Above all, however, Delville considered art to play a key role in uplifting people from their blindness. The true artist was an initiate who would present images which would teach and transform human nature.[7]

Delville had a special interest in monumental art for public spaces. Many of his paintings were very large, such as Les Forces (1924), Les Dernières Idoles (1931), and La Roue du Monde (1940).

Paintings, exhibitions, and prizes

These are a few noteworthy works:

- Le Cycle Passionel was his first exhibited work, in 1885.

- Christ Glorified by the Children won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1895.

- Treasures of Patin in 1895.

- The School of Plato, painted in 1899, won the highest honor at the Universal Exhibition at Milan.

- Love of Souls won the silver medal of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1900.

- The Man-God.

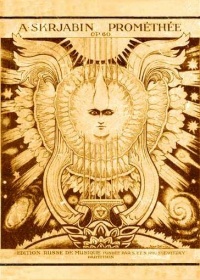

- Prometheus cover art for Scriabin's score, painted in 1908.

- Murals in Palais de Justice, Brussels in 1914.

For a more complete list see Wikipedia.

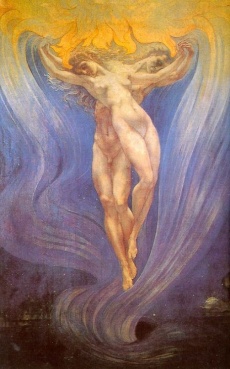

The Love of Souls

The Love of Souls won the silver medal of the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1900. "While lovely and romantic on one hand, this work also portrays the coming together of the female and male aspects of humanity, which only when combined can create the perfect being. This new being is the point of the painting, as the man and woman are actually only the tail, beneath the tail even, of the phoenix which is manifesting above them."[8]

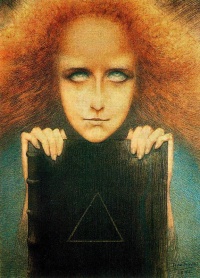

The Portrait of Mrs. Stuart Merrill

A work that drew wide attention is The Portrait of Mrs. Stuart Merrill.

His drawing, executed in chalks in 1892, is strikingly otherworldly. In it Delville depicts the young woman as a medium in trance, with her eyes turned upwards. Her radiating red-orange hair combines with the fluid astral light of her aura.

The hot colors that surround Mrs. Merrill’s head allude to the earthly fires of passion and sensuality. On the other hand, the book on which she rests her chin and long, almost spectral hands is inscribed with an upward-pointing triangle, which represents Delville’s idea of perfect human knowledge, achieved (as he says in his Dialogue), through magic, the Kabbalah, and Hermeticism. As has been widely recognized, the painting, with its references to occultism and wisdom seems to hint at initiation. In that case, the woman’s red aura might refer to her sensual side, which will become more spiritualized as she moves into a different stage of development.[9]

Delville on art

In 1926, The Theosophist published an article by Jean Delville called "Modernism in Painting" in which he expressed his views.

Art, in its human expression, is above all things a psychological, a spiritual, an inner phenomenon; it is of the imagination, and human imagination is an independent faculty... To produce any work of art, to make manifest a beautiful thing, the artist need not depend on the surroundings in which he lives, neither need he reproduce or imitate the objects of those surroundings or look to them for his inspiration.[10]

Writings

The artist also wrote poetry and several books about art. These are some of his most prominent writings:

- Dialogue entre nous. Argumentation Kabbalistique, Occultiste, Idéaliste Bruges: Daveluy Frères, 1895. Dialoguge between Us is a text outlining views on occultism and esoteric philosophy.

- La Mission de l’Art. Etude d’Esthétique Idéaliste. Bruxelles: Georges Balat, 1900. Preface by Edouard Schuré. The Mission of Art discusses idealist art and the social purpose of art.

- La Grande Hiérarchie Occulte et la Venue d’un Instructeur Mondial. Bruxelles: Les Presses Tilbury, 1925.

- "Socialisme de demain." 1912. Article.

- "Du Principe sociale de l'Art." 1913. Article.

- Les Horizons Hantés. Bruxelles: 1892). The Haunted Horizon. Poetry.

- Le Frisson du Sphinx. Bruxelles: H Lamertin, 1897. The Shudder of the Sphinx. Poetry.

- Les Splendeurs Méconnues Bruxelles: Oscar Lamberty, 1922. The Unknown Splendours. Poetry.

- Les Chants dans la Clarté Bruxelles: à l’enseigne de l’oiseau bleu, 1927. "Songs in Clarity." Poetry.

Theosophical Society involvement

Delville became a member of the Theosophical Society in the late 1890s; probably he was introduced to Theosophy by Édouard Schuré (1841 -1929), who was a member of the Society from 1884-1886. "In his [Delville's] book The New Mission of Art (1900), he drew connections between Theosophy and the ideas of Schuré... he added a tower to his house in Forest, painting the meditation room at the top entirely in blue, with the Theosophical emblem at its summit."[11] "Besant gave a series of lectures in Brussels in 1899 titled "La Sagesse Antique" ["Ancient Wisdom"]. Delville reviewed her talks in an article published in Le Thyrse that year.[12] Also in 1899, Delville founded La Lumière, a Theosophical journal. He later wrote for La Revue Théosophique Belge.[13]

Delville was a founder of the Theosophical Society in Belgium and served as its first General Secretary in the years 1911-1913, with Gaston Polak succeeding him.[14] He was a follower of Jiddu Krishnamurti and National Representative of the Order of the Star in the East.[15]

Friendship with Scriabin

In 1908, Russian composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin relocated to Brussels, and there met Delville. Scriabin had been introduced to Theosophy three years earlier.

When Scriabin composed his fifth symphony, Prometheus or "The Poem of Fire" in 1909-1910, Delville created the cover art for the score.

Delville, and perhaps Scriabin, had joined a secret cult within Theosophy called "Sons of the Flames of Wisdom." They worshiped Prometheus, because those fires, colors, lights were metasymbols of man's highest thoughts. Fire was Prometheus's stolen gift to man...[16]

Scriabin was delighted with the androgynous face and the symbolism.

Friendship with James Cousins

Theosophist Dr. James Cousins, an Irish writer, critic, and teacher, wrote of his first meeting with Jean Delville:

I here thank God (or whoever it was) who led me in the summer of 1925 to the presence of Jean Delville in Brussels and to the discovery of one of the world's master-artists and most exalted geniuses - an artist who, on the peak of achievement in his craft and in its recognition among those who know, counts it not inexpedient to be publicly identified with Theosophy, and wears, as naturally as he wears his coat, the badge of the National Representative of the Order of the Star in the East. For the joy and inspiration of that meeting, with its immediate merging of mind with mind in the brotherhood of the spirit; for its gift to me of a vast and exalted realm of art, and a glorious ratification of some of my dreams of what the Theosophical spirit in art may accomplish for the beckoning of humanity towards the heights, I would here make acknowledgment...[17]

Dr. Cousins, who greatly admired Russian painter Nicholas Roerich as well as Deville, also wrote: "Jean Delville of Belgium, who, if Roerich be Castor in the firmament of art, is assuredly his true brother Pollux."[18]

Teaching positions and later years

From 1900 to 1906, Delville was a professor at the Glasgow School of Art.[19] Afterward he worked as a professor of drawing at the Académie des Beaux-arts in Brussels until 1937. He completed two large projects at the Palais de Justice and the Cinquantenaire. His later works are more stylized

In the late 1940s, arthritis forced him to stop painting.

He died on his birthday, January 19, 1953.

Additional resources

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 22 articles by or about Delville.

Articles

- Delville, Jean at Theosophy World.

- Jean Delville: Painting, Spirituality, and the Esoteric by Lynda Harris in Quest 90 no.3 (MAY - JUNE 2002).

- Jean Delville at Wikipedia

Notes

- ↑ "Who's Who in the Theosophical Society: Delville, Jean," The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 177.

- ↑ Ted G. Davy, "Arnold, Edwin," Theosophical Encyclopedia (Quezon City, Philippines: Theosophical Publishing House, 2006), 49. Available at Theosopedia.

- ↑ James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville" The Theosophist 47 no.3 (December, 1925), 398.

- ↑ Lynda Harris. "Jean Delville: Painting, Spirituality, and the Esoteric." The Quest 90 no.3 (May-June 2002), 94.

- ↑ "19th Century Painting: Jean Delville (1867-1953) Belgian Symbolist," Boston College Digital Archive of Art at Boston College website.

- ↑ Jean Delville, La Mission de L'Art translated as The New Mission of Art: A Study of Idealism in Art. Translated by Francis Colmer, with an introduction by Cliffor Bax and Edouard Schuré. London: Francis Griffiths, 1910, pp 11-12.

- ↑ "19th Century Painting: Jean Delville (1867-1953) Belgian Symbolist," Boston College Digital Archive of Art at Boston College website.

- ↑ Paul Shapera, "The Art Of Esoteric Symbolism: Jean Delville" at Steampunkopera.wordpress.

- ↑ Lynda Harris. "Jean Delville: Painting, Spirituality, and the Esoteric." The Quest 90 no.3 (May-June 2002), 94.

- ↑ Jean Delville, "Modernism in Painting" The Theosophist 48.1 (October 1926), 74-84.

- ↑ Lynda Harris. "Jean Delville: Painting, Spirituality, and the Esoteric." The Quest 90.3 (May-June 2002), 94.

- ↑ Jean Delville, 'A propos de la Sagesse Antique. Conference de Mme Annie Besant', Le Thyrse 9 (September 1, 1899), pp. 65-6.

- ↑ "Theosophical Magazines" The Theosophist 30 no.9 (June, 1909), 390.

- ↑ "General Secretaries Past and Present," The Theosophical Year Book, 1938 (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 152.

- ↑ James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." The Theosophist 47 no.3 (December 1925), 397.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume II (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 206-207.

- ↑ James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." The Theosophist 47.3 (December 1925), 396-397.

- ↑ James H. Cousins, "The Life and Work of Jean Delville, Theosophist Painter-Poet." The Theosophist 47 no.3 (December 1925), 396.

- ↑ "19th Century Painting: Jean Delville (1867-1953) Belgian Symbolist," Boston College Digital Archive of Art at Boston College website.