Wassily Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (Russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Канди́нский) was a Russian abstract expressionist painter who was heavily influenced by Theosophy. He wrote a hugely influential book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, and taught at the Bauhaus.

Early life and education

Wassily Wassilyevich Kandinsky was born on December 4, 1866 in Moscow. His father, a wealthy tea merchant, was from an aristocratic family. In 1871 Wassily's family moved to the Crimea, and the boy attended school in Odessa. He excelled in his studies, and returned to Moscow in 1886 to study law and political economy. After he was awarded a degree in 1892, he taught jurisprudence at Moscow university.

His career path in academia seemed to be well established when he "turned down the offer of a professorship at the University of Dorpat in Estonia and went instead to Munich to study painting."[1] As a young boy he had always loved music and art – playing piano and cello, and painting in oils. "Art and music, ranging from traditional Russian religious icons and Rembrandt oils to a performance of Wagner's Lohengrin, left profound impressions on him... An 1895 Moscow exhibit exposed Kandinsky to the French Impressionists, and his feelings upon seeing Monet's Haystack seemed to predict the destiny that awaited him."[2]

Family life

In 1892, he married his cousin, Anna Chimyakina, who was also an artist. Their marriage split apart in 1904, and they finally divorced in 1911. Around 1901, he became involved with a German painter, Gabriele Münter, a student at the Phalanx art school. They traveled together and married for a brief time. Finally, he met Nina Nikolayevna Andreevskaya, a young Russian. They married in 1917 and remained happily together until his death in 1944. They had a son named Vsevolod.[3]

Artistic career

Because young artists in Munich in the 1890s were exploring abstract, primitive, oriental, and medieval styles in the Jugendstil movement, Kandinsky had the opportunity to move in avant-garde art circles while he pursued traditional training. In 1901 he broke away from the academy to form an artists' association called the Phalanx which gave him an outlet for exhibition. He also gained experience in teaching art and built a reputation that helped him into major exhibitions like the 1902 Berlin Secession and the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1904. He began

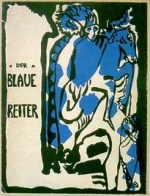

to travel Gabriele to Germany, Italy, Holland, Tunisia, and France during 1903-1908; and he developed his own style. Back in Munich, under "the impact of the Fauvist color, combined with a primitiveness and directness attributable to his Russian heritage, the artist began producing major expressionist landscape paintings." He organized the Neue Künstler Vereinigung [NKV, the New Artists' Association] in a revolt against the Munich Secession. After 1911, his continued movement toward abstraction led to a split in the group, and Kandinsky, with Franz Marc, formed Der Blaue Reiter [the Blue Rider], named after a Kandinsky painting. They published a journal, called an almanac, that emphasized spiritual reality expressed in diverse styles of art. During this same period, Kandinsky was writing his pioneering work Über das Geistige in der Kunst, or Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which was published in 1912.[4]

Concerning the Spiritual in Art

Über das Geistige in der Kunst was one of the most significant legacies of Kandinsky's life. It was published in English as The Art of Spiritual Harmony and, later, as Concerning the Spiritual in Art. It has been translated into over 20 languages, with many editions and printings.

Kandinsky's theories on art begin with an exposition on the life of the spirit, which he envisions as a triangle - later a pyramid - moving forward and upward. Each individual inhabits some level of the triangle and must find spiritual food appropriate to that level of development. Artists at each level are understood by the other people at that level, so that artists at the higher levels are understood by fewer and fewer. "The solitary visionaries are despised or regarded as abnormal and eccentric.[5] He likens the upward spiritual movement to a revolution. "Literature, music and art are the first and most sensitive spheres in which this spiritual revolution makes itself felt."[6] He goes on to use the words of Maurice Maeterlinck and the music of Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy, and Alexander Scriabin as examples of how artists can use their media to convey spiritual meaning to those who are receptive.

In Kandinsky's viewpoint, paintings should convey the emotions of music, and music should have a language of color. Concerning the Spiritual in Art discusses not only the physical impressions of the visual arts, but the psychic effects of forms and colors, their rich associations and relationships. Kandinsky explores the merging of the arts and the concept of synesthesia, wherein the experience of one sense is linked to another sensory experience in an involuntary response. Theosophists like Scriabin and Claude Bragdon also experimented with keyboard instruments that displayed colors as certain musical tones were being played. The psychic effect of color is profound, and specific colors are linked to experiences of sound, taste, scent, and texture. Colored lights are used in chromotherapy that can affect the entire body.

A large portion of Kandinsky's text discusses specific colors - their qualities, influences, and associations - and the inner meanings of forms such as geometric shapes. One remarkable section gives great insight into the warm (yellow) and cool (blue) colors, and the light (white) and dark (black).

The artist must consider the composition of the art work and the relationships within it. The combinations of colors and forms are expressions the artist's inner need, which is comprised of three elements:

- Every artist, as a creator, has something in him which calls for expression (this is the element of personality).

- Every artist, as child of his age, is impelled to express the spirit of his age (this is the element of style).

- Every artist, as a servant of art, has to help the cause of art (this is the element of pure artistry,which is constant in all ages and among all nationalities).

Kandinsky goes on to discuss the "spectator" of art; the dance-art of the future; the role of artists; and the sources of inspiration: impression, improvisation, and composition.

The artist must have something to say, for mastery over form is not his goal but rather the adapting of form to its inner meaning...

The artist has a triple responsibility to the non-artists: (1) He must repay the talent which he has; (2) his deeds, feelings, and thoughts, as those of every man, create a spiritual atmosphere which is either pure or poisonous. (3) These deeds and thoughts are materials for his creations, which themselves exercise influence on the spiritual atmosphere.

If the artist be priest of beauty, nevertheless this beauty is to be sought only according to the principle of the inner need, and can be measured only according to the size and intensity of that need.

That is beautiful which is produced by the inner need, which springs from the soul.[7]

Famous paintings

The Kandinsky.Net website shows 547 of his art works arranged by year, and a gallery of the fifty most important. Another large gallery online is at Wikiart. For discussions of Kandinsky's artistic periods and development, refer to Wikipedia and Guggenheim.org.

Here are a few of the artist's most famous works:

- Empor (in Alto), 1900 - This work has an effect of energy rising along a vertical line. The arrow-like base supports half-circles of delicate colors.

- The Blue Rider (Der blaue Reiter), 1903 - This transitional work shows the artist moving away from representation into abstraction; it inspired Der Blaue Reiter group of artists and their journal. He used a horse-and-rider motif in many works.

- The Blue Mountain (Der blaue Berg), 1909 - Kandinsky creates a dissonance in bright colors under a Fauvist influence, representing the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse.

- Composition VII, 1913 - Kandinsky made at least 30 drawings and at least 10 studies in oil for this large canvas, which may represent the height of his work in Munich.

- Farbstudie-Quadrate, 1913 - This "color study" explores primary colors in concentric circles within square enclosures. The twelve squares are similar structure, while each has an entirely different impact on the eye and psyche.

- Circles in a Circle, 1923 - The closed space of the simplest of forms, a black circle, is filled with bubbles of color and diagonal lines; the circle becomes more prominent because of the forceful diagonals in the background.

- Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925 - This is another very large canvas - two meters wide - employing varied forms and colors in a complex relationship.

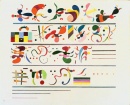

- Succession, 1935 - This late work elicits thought of bars of music, or a symbolic language of whimsical shapes telling a story.

Bauhaus

The Bauhaus offered a position in its faculty, and Kandinsky worked there from 1923-1933, when the school was closed by the Nazis. Several other people associated with the Bauhaus were Theosophists or highly influenced by Theosophy, including Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, and Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel, the widow of Gustav Mahler who had married Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. After the school closed, Kandinsky moved to Paris, and lived there until his death on December 13, 1944.

Writings

- Über das Geistige in der Kunst. München Piper, 1912. In German, this work has undergone many editions and printings. It has been translated into Russian, Japanese, French, Spanish, Chinese, Basque, Turkish, Korean, Indonesian, Bulgarian, Greek, Czech, Dutch, Romanian, Swedish, Hebrew, Finnish, Portuguese, Italian, Serbian, etc. Here are prominent English editions:

- The Art of Spiritual Harmony. Translated into English by Michael Sadleir (London: Constable and Company Limited, 1914; also Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914.) Available at Internet Archive, Google Books, and Hathitrust. This was the first unabriged English translation.

- Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Edited and translated by Hilla Rebay (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1946), for the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Available at Internet Archive. 164 pages, with color plates and other illustrations.

- Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Dover Edition translated and with introduction by M. T. H. Sadler (New York: Dover Publications, 1977). 57 pages with black-and-white illustrations.

- Punkt und linie zu flache. München: Albert Langen, 1926. Many German editions and printings. Translated in Russian, French, Spanish, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Bulgarian, Polish, Czech, Swedish, etc. English editions:

- Point and Line to Plane: Contribution to the Analysis of the Pictorial Elements. Translated by Howard Dearstyne and edited by Hilla Rebay. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1947. Available at Hathitrust and Internet Archive. 226 pages. 127 illustrations.

Influence of Theosophy

Kandinsky was never a member of any Theosophical society, but read extensively in Theosophical concepts, including the seminal work The Secret Doctrine by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

Wassily Kandinsky was an avid student of occult and mystical teachings. Theosophy provided the main structure for his lessons in spirituality, but he certainly enriched his studies with other material. As his spiritual awareness evolved, so too did his art. Ideals that he was previously content to express in Symbolist form, later shed their casings as they expanded through abstraction. As Theosophical teachings on thought forms and the correlation between vibrations, color, and sound influenced his work, he began to rely very little on form. Shape, line, and color became his main tools for creating a visible image of unseen events in the astral world.[8]

He quoted Blavatsky's The Key to Theosophy in writing about the methods used by primitive and ancient cultures in dealing with matters that cannot be explained by materialistic science.

These methods are still alive and is use among nations whom we, from the height of our knowledge, have been accustomed to regard with pity and scorn. To such nations belong the Indians, who from time to time confront those learned in our civilization with problems which we have either passed by unnoticed or brushed aside with superficial words and explanations [such as hypnotism]. Mme. Blavatsky was the first person, after a life of many years in India, to see a connection between these "savages" and our "civilization." From that moment there began a tremendous spiritual movement which today includes a large number of people and has even assumed a material form in the Theosophical Society. This society consists of groups who seek to approach the problem of the spirit by way of the inner knowledge... Theosophy, according to Blavatsky, is synonymous with eternal truth. "The new torchbearer of truth will find the minds of men prepared for his message, a language ready for him in which to clothe the new truths he brings an organization awaiting his arrival, which will remove the merely mechanical, material obstacles and difficulties from his path." And then Blavatsky continues, "The earth will be a heaven in the twenty-first century in comparison with what it is now." and with these words ends her book.[9]

The 1905 book Thought Forms by Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater clearly had a major impact on Kandinsky's thinking when he wrote Concerning the Spiritual in Art:

[the influence of Theosophical writers] was far greater at this crucial juncture in his development than the artist could bring himself to disclose at the time. His entire Weltanschauung, his worldview of life itself, was shaped by their philosophy of the occult...

On the Spiritual in Art is, after all, a treatise on the aesthetics of painting, and a good many of what appear to be purely aesthetic observations—about form, about color, about spatial relationships—are similarly derived from theosophical pronouncements. In this respect, Thought-Forms — the theosophical classic by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater that was translated into German in 1908— seems to have been of capital importance. When, for example, in the chapter of On the Spiritual devoted to “The Language of Forms and Colors,” Kandinsky sets about the task of assigning specific meanings to specific colors, he is clearly appropriating an occult practice.

Thus about the color blue, Kandinsky writes that “the deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man toward the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, the supernatural”—an obvious echo of the assertion in Thought-Forms that “the different shades of blue all indicate religious feeling.” When he writes about green that “pure green is to the realm of color what the so-called bourgeoisie is to human society: it is an immobile, complacent element, limited in every respect,” this description, too, bears a distinct resemblance to the statement in Thought-Forms that “green seems always to denote adaptability; in the lowest case, when mingled with selfishness, this adaptability becomes deceit,” etc. And while it is true that Kandinsky takes certain liberties with this theosophical practice, deviating from some of the meanings assigned to colors in Thought-Forms and other occult writings, he nonetheless follows the practice of conferring upon each color a significance that is finally metaphysical.[10]

Later years

After the Bauhaus school closed, Kandinsky with Nina moved to Paris; he became a French citizen in 1939. He continued painting, producing some of his most well-known works. He died at Neuilly-sur-Seine on December 13, 1944 of a cerebrovascular disease.

Additional resources

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 9 articles by or about Kandinsky.

Websites

- Wassily Kandinsky Facebook group.

- WassilyKandinsky.net offers 511 paintings, 91 photos, biography, books, videos, quotations, and more.

- Wassily Kandinsky Natal Horoscope at Khaldea.

- WassilyKandinsky.org offers biography, quotations, and analyses of paintings.

Articles

- "Art, Theosophy, and Kandinsky" by John Algeo. Theosophy Forward.

- Kandinsky's Thought Forms and the Occult Roots of Modern Art by Gary Lachman. Quest 96 no.2 (March-April 2008): 57-61.

- Kandinsky and Theosophy by Catherine Wathen. Theosophy Forward.

- "Wassily Kandinsky: 8 of the Abstract Painter's Most Famous Works and Facts about His Life" by Mikey Smith. Daily Mirror December 16, 2014.

Video

- Kandinsky, Spiritual Insight, and Abstract Art by Dan Noga

- "What Does Colour Sound Like? Kandinsky and Music" from Listening In YouTube channel.

Notes

- ↑ Richard Stratton, "Preface to the Dover Edition" Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), v.

- ↑ Richard Stratton, "Preface to the Dover Edition" Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), v.

- ↑ "The Three Wives of Wassily Kandinsky," Olga's Gallery blog. Posted May 3, 2003 a Olga's Gallery.

- ↑ Richard Stratton, "Preface to the Dover Edition" Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), vi-viii.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), 8.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), 14.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1972), 54-55.

- ↑ Kathleen Hall "Theosophy and the Emergence of Modern Abstract Art" Quest 90 no.3 (May-June 2002).

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover, 1977), 13-14.

- ↑ Hilton Kramer "Kandinsky & the Birth of Abstraction" The New Criterion 35.4 (December 2016). From Features, March, 1995. Available at New Criterion website.