Wanda Dynowska

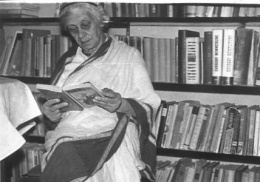

Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi (June 30, 1888, in St. Petersburg; March 27, 1971 in Mysore) was a Polish Theosophist, writer, translator, publisher, social activist, promoter of intercultural exchanges between India and Poland, and the founder of the Indish-Polish Library. In India she was known mostly as Umadevi a name given to her by Mahatma Gandhi,[1]and to some she was known as Tenzin Chodon.[2]

She was attracted to Theosophy at an early age because it offered in her own words “unlimited perspectives” because “life has neither beginning nor end, it is an everlasting creativeness, an inseparable attribute of the highest consciousness, God.” Dynowska remained interested in the human spiritual dimension throughout her life and studied world religions. For a while, she favored the Liberal Catholic Church in Poland.[3]

She helped expand the hearts and minds of many Indians, among others, was on her own quest for spiritual elevation, unconcerned with being a social helper-celebrity. She was a linguist, a woman of literature, a loving human, and an adamant fighter of oppressors, who carried with her the pain the Soviets inflicted upon Poland to her death.[4]

Early Years

Wanda Dynowska was born in St. Petersburg on June 30, 1888, a time when Poland was still partitioned and occupied by Russia, Prussia and Austria.[5] She was the daughter of lawyer Eustachy and Helena née Sokołowscy [6]

The family spent much of the time on their estate in the countryside in Latvia which had a beautiful forest and lake around. The house was a meeting place, a center of intellectual discussions and profound Polish patriotism. Thus, growing up, Wanda learned a lot about spiritual and Polish culture.[7]

Educated at home by private tutors, the young Wanda became fluent in Polish, German, French, Spanish, Italian and English, as well as Latvian which she spoke with the local country people. She also spoke Russian, though only when she absolutely had to.[8] Later in life she would add Tamil and Hindi to her arsenal of language mastery.[9]

She also read a lot when she was young, including The Bible, the Bhagavad Gita and the Koran, Polish Romantic poetry and the works of Polish philosophers of the 19th century. She studied Romance studies at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow and the University of Lausanne.[10]

Activities in the Theosophical Society

The family house in Istalno was open to artists, writers, and political activists. The salon reverberated with discussions which for the young Wanda were a great school of intellectual culture and patriotism. One of the visitors was Tadeusz Miciński, an influential Polish poet, gnostic, and playwright and prominent member of the Warsaw Theosophical Society. He might have influenced the awakening of Wanda's theosophical interests.[11] However, when the Polish occultist Antoni Sobieski asked her what had brought her to esoterism, she responded:

“My beliefs came from my own meditations and presumably recollections of past incarnations. I concluded between 16 and 18 years of age that the only logical explanation for the mysteries of life including mental, moral, social, and other inequalities is reincarnation.”[12][13]

Thus, the belief in reincarnation might have attracted her to Theosophy and she was also greatly impressed by the first book of Theosophy that she read, An Esoteric Philosophy of India. Her meetings with prominent Russian Theosophists in Moscow played also an important role in her Theosophical biography. In the house of these new friends, she spoke only French due to her patriotism, which was tolerated with all kindness. She did not join the Russian Theosophical Society but joined the Italian Society. She spent 1917 and 1918 in the Crimea and, believing in the emergence of an independent Poland, made plans to establish a Polish branch of the Society. In 1919, after Wanda had moved to Warsaw, she began the first talks aimed at establishing the Polish Theosophical Society maintaining close contact with theosophists from the former Warsaw Theosophical Society from the period of the Russian partition. The same year, with money obtained by pawning jewelry and donations by friends, she travelled to Paris to obtain Anna Besant's consent to establish the Polish Theosophical Society. She did not meet her in person, but Wanda's efforts persuaded Besant to agree in writing to establishing a Polish Section. Moreover, Wanda met Jiddu Krishnamurti in person.[14][15][16]

Annie Besant, who was President of the Society at the time, emphasized that the legal registration of the society in a country where the Theosophical Society had been treated as illegal was of particular importance.[17][18]

Wanda threw herself into the vortex of Theosophical activity after the death of a young man named Szczęsny, who had asked for her hand in marriage. She became the founder and guiding spirit of the Polish Theosophical Society. She inspired much of the work of the society and collaborated with the English Theosophist Miss Arnold, who was sent to Poland by Annie Besant, to establish an Esoteric School there.[19][20]One example of her efforts is a letter addressed to the General Secretary in the United States asking for financial aid for founding a colony of Theosophical workers with a children’s school.[21]

In July 1923, she received a diploma for organizing the Polish section of the Theosophical Society from Jinarajadasa at the Vienna congress. Shortly thereafter, she became the secretary general of the Polish Theosophical Society. She gave lectures in many Polish cities, initiated the creation of the cooperative publishing house Adyar, and made numerous translations of Theosophical literature. Since 1921 she had been editing the periodical Theosophical Review (Przegląd Teozoficzny) in Warsaw and she also published a lot of her own works.[22][23]

Wanda Dynowska was always captivated by the Theosophical ideal of universal brotherhood. At the end of the society’s first five years, she decided to create a small community in Warsaw, like the one in Paris where she had stayed for a while. She decided to invite Dr. George Arundale and his wife Rukmini Devi to Poland. Their two visits were an event of great measure and afterwards several Polish theosophists including Wanda were admitted to the Order of Servants. In 1925, based on the English federation, she formed with others "Le Droit Humain" – the Polish Federation of the Order of Universal United Mixed Freemasonry - and until the creation of an independent Polish federation, Wanda, was also a representative of the Mixed Masonry in the Supreme Council in Paris.[24][25]

In the 1920s, Wanda started to organize the Liberal Catholic Church in Poland. She translated the liturgy of the Church into Polish and invited Bishops Mazel and Wedgwood to Poland.[26]

Polish Theosophists were interested in Rosicrucianism and often had close relations with Rosicrucians and were often members of masonic lodges.[27]

Wanda Dynowska participated in all European congresses of the Theosophical Society and in the conventions of the Order of the Star in the East. She lived in Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, France, Yugoslavia, Romania, Hungary, and Great Britain. In 1927, she lectured in major cities in England and Scotland.

Like many Polish theosophists, she belonged to the Order of the Star in the East. In August 1927, Theosophical Society President Annie Besant, who was on a lecture tour of European capitals, came to Warsaw August 30-31. She had a series of group and individual meetings with Polish theosophists.[28][29][30]

Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi in India

Wanda Dynowska left Poland in the autumn of 1935 and moved to India. She attended the Congress of the Theosophical Society in Adyar that year. From the moment of her arrival, she immersed herself in Indian life at many levels: spiritual, intellectual, social, and political.[31]

She met Mahatma Gandhi in the first years of her stay in India and became a close coworker, involving herself passionately in the Indian independence movement. She was very interested in the social conditions at the time and met with various Hindu groups. She wrote prolifically during that time,[32][33], including poetry dedicated to her Hindu mentors and one to Maurycy Frydman, a Jewish Pole and fellow Theosophist. She also wrote articles for the American Theosophist, dedicating one article to Adyar, calling it “The Heart of the World”.[34]She studied yoga with Sri Ramana Maharishi and frequently returned to the holy mountain Arunchala where she was initiated into deeper levels of Hinduism, and made a pilgrimage to Ishwar Ashram in the Himalayas to study Kasmiri Saivism with Swami Lakshmanjoo.[35]

When World War II broke out, she attempted to return to Poland without success. Thus, she turned her attention to Polish people who were able to leave the Soviet Union and reached India via Iran, introducing them to Indian living conditions.[36][37] She was especially drawn to the children from her beloved homeland and shared with them what she had: serenity, a dedication to peace and respect for all cultures, and her knowledge India.[38]

At the beginning of 1944 Dynowska, together with Maurycy Frydman, began publishing the Polish Indian Library. The first volume was titled A Hindu Pilgrimage up to the Himalayas. In the ensuing decades many volumes appeared on a variety of topics. Then she launched her Indo-Polish Library with Peter Jordan’s book, First to Fight. Dynowska also translated a great number of Theosophical works. But her true opus magnum was her six-volume Indian Anthology. Wanda continued to work on the Polish Indian Library until 1969.[39][40]

Last Years

Wanda Dynowska broke contact with all the organizations she had belonged to, including the Theosophical Society, at the end of the 1940s or the very early 1950, although she did maintain occasional contact with Adyar. Based on accessible source it was because of the teachings of Krishnamurti. She shared her own mystical experiences in letters to friends, edited Krishnamurti’s lectures in Polish and was concerned with spreading his teachings.

She also managed to visit Poland twice, once in 1960 and again in 1969, where she met with Bishop Karol Wojtyla (later Pope John Paul II). Her letters to friends reveal that she remained interested in problems in Poland and felt homesick.

In 1960 she began working with Tibetan children who had lost their parents in the Chinese invasion and the passage across the Himalayas. She went to Northern India ending up in the village Upper Dharmsala. In the subsequent years she wintered in Adyar or Mysore and traveled to Upper Dharmsala, a home of the Dalai Lama, in the spring, where she would help the Tibetan refugees. She was in permanent contact with the Dalai Lama[41][42], who shared in the movie “Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi” how she had convinced His Holiness, for a time, to become a vegetarian. In the same interview he mentions that she was also sometimes called “The Mother”.[43]Over the years, Wanda devoted more and more time educating the Tibetan youths, founded schools and was instrumental in obtaining fellowships for a great number of the youths in Switzerland. Even during that time she continued her writings.

In a letter to her friend Frydman written in October 1970 she shared that she had left Dharmsala forever because of health issues. In the autumn of 1970, she moved to a Roman Catholic convent in Mysore where she died on March 27, 1971.[44][45] When she died, she received last rites from a Polish Catholic priest, and her funeral rites were performed by Tibetan lamas, true to her belief that all religions are one, containing within them the essential truth.[46] N. Sri Ram, the fifth International President of the Theosophical Society mentioned Wanda when addressing the attendees of the 82nd and 96th International Convention in Adyar and talked about her translation of Theosophical writings into Polish[47] as well as her ardent work for the Tibetans of India.[48]

Wanda Dynowska always emphasized that it was not appropriate for others to follow her life’s path, that she never played the part of a guru but was one who incessantly searched for the Truth.[49][50]

Online Resources

- Trailer of the movie: Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi [1]

- Special Preview of the move: Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi (including an interview with Tim Boyd, International President of the Theosophical Society [2]

- Interview with his Holiness, the Dalai Lama from the movie: Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi [3]

- Article about the movie “Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi. [4]

- Article: Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture [5]

- Article: The Forgotten Polish Woman Who Counseled Mahatma Gandhi And The Dalai Lama [6]

Notes

- ↑ Manning, Julian. The Forgotten Polish Woman Who Counseled Mahatma Gandhi And The Dalai Lama.Homegrown Fresh. March 13, 2017. https://homegrown.co.in/article/800695/wanda-dynowska-the-polish-woman-behind-gandhi-and-the-dalai-lama Accessed on 10/11/21

- ↑ Staniewski, Wlodimierz, Founder and Director of the Centre fo Theatre Practices, In: Special Review of the Movie: Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H29as3Co1ME. Accessed on 10/12/21

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. WandaDynowska/Umdevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Manning, Julian. The Forgotten Polish Woman Who Counseled Mahatma Gandhi And The Dalai Lama.Homegrown Fresh. March 13, 2017. https://homegrown.co.in/article/800695/wanda-dynowska-the-polish-woman-behind-gandhi-and-the-dalai-lama Accessed on 10/11/21

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. WandaDynowska/Umdevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Bialowski, Maciej, Translator & Author, in the Special Review of the Movie: Enlightened Soul: The Three Names of Umadevi. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H29as3Co1ME. Accessed on 10/12/21

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Manning, Julian. The Forgotten Polish Woman Who Counseled Mahatma Gandhi And The Dalai Lama.Homegrown Fresh. March 13, 2017. https://homegrown.co.in/article/800695/wanda-dynowska-the-polish-woman-behind-gandhi-and-the-dalai-lama Accessed on 10/11/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umdevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Hess, Karolina Maria, MA Annie Besant & Poland. In: Fota Newsletter No. 8, Autumn-Winter 2017-2018.

- ↑ Besant, A. From the Editor, The Theosophist 1909, Vol. XXX, p. 194.

- ↑ Hess, Karolina Maria, MA. The Beginnings of Theosophy in Poland: From Early Visions to the Polish Theosophical Society In: The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture, No. 13 (1/2015).

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Theosophy in Poland. The Messenger 9.5, October 1921, p. 134.

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ L. Chajn, Freemasonry in the II Rzeczpospolita , Warsaw 1984; L. Hass, Ambicje, calculy, reality , Warsaw 1984; L. Hass, Principles in the hour of trial, Warsaw 1987

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Hess, Karolina Maria, MA. The Beginnings of Theosophy in Poland: From Early Visions to the Polish Theosophical Society In: The Polish Journal of the Arts and Cutlure, No. 13 (1/2015)

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Hess, Karolina Maria, MA Annie Besant & Poland. In: Fota Newsletter No. 8, Autumn-Winter 2017-2018

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Dynowska, Wanda. The Heart of the World The American Theosophist, Feb. 1937, 25, 2; Religious Magazine Arhicve, page 32

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ okarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ The Holiness the Dalai Lama. Enlightened Soul: Interview with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOL-KZl3HQo. Accessed on 10/11/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105

- ↑ Tomaszweski, Irene. Wanda Dynowska/Umadevi: A Polish Guide to Indian Culture. Cosmopolitan Review: A Transatlantic Review of Things Polish, in English. 2013 Vol. 5, No. 2 Summer/Features. http://cosmopolitanreview.com/wanda-dynowska-umadevi/ Accessed on 10/8/21

- ↑ Ram, Sri. N. Presidential Address to the 82nd Convention of the Theosophical Society in Adyar on December 26th, 1971 American Theosophist 46.3. March. 1958

- ↑ Ram, Sri. N. Presidential Address to the 96th Convention of the Theosophical Society in Adyar on December 26th, 1971 American Theosophist 60.2. Feb. 1972

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. About Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20180219153807/http://www.jkrishnamurti.republika.pl/rozne.dynowska.bio.htm Accessed on 10/10/21

- ↑ Tokarski, Kazimierz. Wanda Dynowska-Umadevi. A Biographical Essay. Translated by Anna Sowinska. In: Theosophical History, July 1994, pages 89 - 105