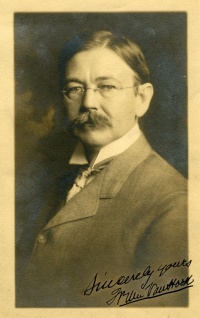

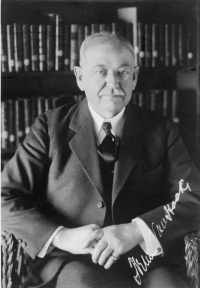

Weller Van Hook

Dr. Weller Van Hook was a prominent and innovative surgeon in Chicago, and served for five years as the President (General Secretary) of the American Theosophical Society.

Early years

The Van Hook family came from a Burgomeister General of Holland, whose descendants emigrated to New Amsterdam (now New York City), and later settled in Indiana. Weller Van Hook was born to William Russell and Tillie (Weller) Van Hook on May 14, 1862 in Greensville, Indiana. His father was a physician. In 1881 the son began a course of study at the University of Michigan, and was awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1884. After a year at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Chicago, he graduated in 1885. From July 1885 through December 1886 he interned at the Cook County Hospital. When a peaceful labor demonstration turned into the Haymarket riot of May 4, 1886, Dr. Van Hook admitted a policeman, Mathias J. Degan, to the hospital. The doctor helped to perform the post-mortem examination that provided important evidence used in prosecuting eight anarchists.[1]

Medical career

Dr. Van Hook established a practice on the west side of Chicago from 1887 until 1894. In 1892, he became a professor in the principles of surgery at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and also taught at a hospital. He gave up his practice in 1894 and spent some months engaged in postgraduate study of surgery in Vienna, Berlin, London, and Paris. On his return, Dr. Van Hook campaigned to modernize the practice of medicine, and was quoted as writing:

The grey heads cling to the denial of bacterial significance of disease as, when a boy, I heard them doing in Central Music Hall at the Meetings of the American Medical Association. Even then, after the pathogenic powers of the pus microbes were known, many great surgeons still adhered to the primitive Listerian antiseptic methods.[2]

Dr. Van Hook could be intolerant of his colleagues in their rejection of modern methods, but his warm attitude toward patients is evident in another quotation:

The beginning of anesthesia constitutes a period of anxiety for both patient and surgeon. Too often, the anesthetist fails to treat his patient as a fellow mortal and starts to anesthetize him without formality. Twenty seconds may be spent in saying to the patient, 'Mr. Jones, I am Dr. Smith and your surgeon Dr. So and So wishes me to administer your anesthetic.' A pleasant word or two about any promising feature of the outlook from the patient's point of view will give the patient confidence in the man who is to have his life in charge for a while and will often have the effect of distinctly quieting the nervous sytem. Boisterous and confused conversation and activity, are most undesirable about a patient who is going to sleep. [3]

In the late 1890s, Dr. Van Hook performed surgeries mainly at Wesley Hospital at 25th and Dearborn, adjacent to the Northwestern Medical School. When surgery was performed at the Medical School in that era, patients had to be carried on stretchers to and from the hospital in the open air. Patients came from distant locations, attracted by his reputation for superior surgical ability, modesty, even temper, and kindly manner. He had a staff of seven assistants, several of whom went on to become eminent surgeons and professors.[4] Dr. Van Hook and his colleagues pioneered in techniques such as the use of nitrous oxide for anesthesia and microscopic examination of excised tumors. He also "devised a new operation of transplanting one ureter into the one on the opposite side to salvage the kidney on the side of the obstructed ureter."[5]

Northwestern Medical School lists Dr. Van Hook as Professor of Surgery 1896-1908, and chairman of the Department of Surgery 1899-1908.[6] When he joined the medical faculty in 1896, the school had been making admission requirements more rigorous, but soon that academic objective came into conflict with the administration's desire to increase matriculation, which exceeded 600 in 1902-1903, compared to 321 in 1895-1896. Bayard Holmes wrote: "Van Hook went to Northwestern [in 1896] where his enthusiasm was slowly drowned out by the economic and pedantic exploitation of the splendid foundation laid so patiently and devotedly by [the early founders of the school]."[7]

Dr. Van Hook was a member of several professional groups: American Medical Association, Illinois State Medical Society, Chicago Surgical Society, and Chicago Medical Society.[8]

Family life

On June 16th, 1892, Dr. Van Hook married another physician, Anna Charles Whaley of St. Louis.[9] She was a student of his friend and colleague Dr. James B. Herrick.[10] Anna was a refined, cultured woman who became very involved with Theosophy. Clara Codd described her as a beauty, who "reminded me of an ancient Greek."[11] Hubert Van Hook, born to Weller and Anna on June 3, 1896, was viewed as a possible vehicle for the World Teacher until Charles Leadbeater decided to cast Jiddu Krishnamurti in that role.

Introduction to Theosophy

One of the doctor's biographers stated that he became interested in Theosophy when he picked up the book Esoteric Christianity (published in 1901 by Annie Besant) that his wife had left on a table.[12] Mrs. Van Hook apparently disagreed with this account of events, however.[13]

In 1904, Dr. Van Hook was introduced to international Theosophical lecturer C. Jinarājadāsa when he spoke in Chicago,[14] Mr. Jinarājadāsa stayed in Chicago from September 1904 to the end of June, 1905, where he was "doing admirable work for the Branch, conducting a number of classes, and giving public lectures on Sunday evenings."[15] CJ remembered his meeting with Dr. Van Hook in the foreword to his little book, In His Name:

We met only for an hour, but I felt from the moment I saw you that I had a message to give. What that message is you will find in the following pages.

You have come to a point in your life when you feel you cannot any longer be fully of the world. You are established in an honorable career and know that time will bring you success and ease; but already you feel that you cannot work for success alone. You feel you must be an idealist in your profession, and be loyal to the ideal you see even though it means suffering and humiliation. You are in the position that hundreds are in to-day, but you are different from them in that you believe that the ideal that compels your obedience is not a thing of your imiagination, but is the first glimpse of a Personality whom you would like to call The Master. You feel that if this Master really exists and you could know him, then you could be utterly true to him in every way regardless of what comes.

You know further that you cannot seek this Master by retiring into some monastic seclusion, in order that by meditation and contemplation there you might commune with him. You are not free to consider your welfare only, for there are those depending upon you for their needs. For their sakes you know you must engage in a worldly career; but while you are so engaged you would like, if it be possible, at the same time to serve the Master in some way. It is because there is such a way that I write these pages for you, and for others who are opening their eyes to those higher human possibilities that you have already seen.

Each human soul has some message to give to every other human soul, and what I write is my message to you just now. It is not mine in reality, for it came to me from other human souls, and I am giving to you as a brother what others as Brothers have given to me.[16]

"Anna W. Van Hook" is listed among delegates from the Chicago Branch to the Nineteenth Annual Convention of the American Section. It was held in Chicago on September 17-18, 1905.[17] The following year, both Dr. and Mrs. Van Hook were delegates.[18]

Years as President of American Theosophical Society

By the time of the American Theosophical Society convention in 1907, a very insistent committee had persuaded Dr. Van Hook to run for the office of General Secretary of the organization.

During his tenure, Dr. Van Hook created the Rajput Press at his own expense to print the information booklets that were then called "propaganda." He organized the Theosophic Book Corporation. Prominent lecturers traversed the country: L. W. Rogers, Irving S. Cooper, Fritz Kunz, C. Jinarajadasa, and in 1909, Annie Besant in an extensive tour. Under his leadership, Chicago became the base for the Karma and Reincarnation League (or Legion),[19] and he also established a number of other initiatives such as:

- Woman's Protective League (or Legion)

- Stereopticon Bureau

- Prison League

- League for the Little Brothers (to protect animals)

Another of Van Hook's interests was an attempt to establish a permanent headquarters in Chicago:

He hoped to interest the membership in a parcel of land available on the shores of Lake Michigan in the South Shore district of Chicago for a National Headquarters. About this time the movement to found 'Krotona' in California gained momentum, and money that would have been available for a Section Headquarters was diverted into that project. As there was insufficient money for both undertakings, Dr. Van Hook's plans faded away.[20]

His dedication to the Theosophical Society led to a decline in his medical practice, and in 1911 he resigned as General Secretary in order to re-establish himself professionally. He wrote a letter naming A. P. Warrington to fill out his term in office.

Hubert Van Hook and C. W. Leadbeater

According to genealogist Will Johnson,

In 1907, Weller became the General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in the United States, and was one of the vocal supporters of Leadbeater during the scandal that eventually forced Leadbeater to temporarily resign. About that time, Leadbeater while on an American lecture tour, met their son Hubert and in the summer of 1907, Hubert and his mother stayed with Leadbeater in Germany where some of Hubert's past-lives were written out. Leadbeater and Besant both believed Hubert was the appropriate vessel for the indwelling of the expected Lord Maitreya. Anna and Hubert moved in 1909 to Adyar, India with high hopes for his future. They must have been disappointed when another vessel, Krishnamurti had already been chosen in the Spring of 1909. Nevertheless, they [Van Hooks] stayed and Anna taught Hubert, Krishnamurti and Krishna's brother Nitya for some time. [21]

In another account of 1907:

About this time, Mrs. Van Hook left Chicago with their son, a lad of nine, to travel in Europe and to meet certain leaders of the Theosophical Society there. It was apparently Dr. Van Hook's idea that his son was destined to a significant future in the Theosophical world and his early education was directed along these lines. After visiting with his mother in Germany, Italy, and Sicily, they returned to the United States and then went to India and lived in the Orient. Much of their time was spent at Adyar, in Madras, India, international headquarters of the Theosophical Society. The education of the boy was carried on by private tutors and supplemented by lectures and conferences with the inner circle of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, where the leaders of the group, philosophic and political were congregated. They remained there for some years."[22]

Later Theosophical work

After Van Hook's resignation from the presidency, A. P. Warrington moved the national headquarters to Los Angeles, establishing the colony of Krotona. Chicago members persuaded the doctor to establish the Akbar Lodge in the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue. "Each member brought his own chair; together they bought back from the Section the familiar platform and desk."[23]

Final years

According to a friend and fellow surgeon, Dr. Chauncey C. Maher:

Dr. Van Hook was of course greatly interested in the metaphysical aspects of his religion and he considered himself, and was revered by his fellow theosophists, as an adept in occultism. He felt that he had the occult power of being able to communicate with other adept leaders of the faith, and told me he conversed frequently with Annie Besant, then in India. I have been told that he had hoped to develop the occult power of clairvoyant vision, in his own field of surgery, i.e., to see with his eyes, what the X-ray reveals on the photographic film, a power that he never achieved.[24]

His physical vigor began to fail and his surgical skill was greatly impaired. His family was apart from him, with his wife still in England. His son had renounced theosophy completely many years before. He was alone... About 1931, he left Chicago and went to a farm near Coopersville, Illinois, where he spent the remaining two years of his life. He had an apoplectic stroke and died June 30, 1933, aged 71. His body was cremated and his funeral supervised by his Masonic Lodge.[25]

Note on Coopersville location: Coopersville, Illinois is an error. Dr. Maher may have meant Coopersville, Michigan or the Coopersville Post Office in Ohio County, Indiana.

Another account states that "Funeral services were held July 5 and were conducted by Englewood Commandery No. 59, Knights Templar."[26]

The Akbar Lodge in Chicago "adopted the practice of celebrating the birthday of Dr. Weller Van Hook as it comes around each year, in memory of his great services to the lodge. In the course of the memorial meeting his writings and teachings are given a prominent place... Dr. Van Hook's birthday is May 14, and Akbar Lodge celebrates it on the nearest lodge night.[27]

Medical writings

Dr. Van Hook contributed to several medical journals and also to the International Text-Book of Surgery.[28] These are just a few of Dr. Van Hook's medical writings:

- "The Advantages and Technique of Capillary Abdominal Drainage," American Gynæcological and Obstetrical Journal (March, 1896). Read before the Chicago Gynæcological Society, January 17, 1896. Accessed online at National Library of Medicine.

- "Air-Distention in Operations upon the Biliary Passages," Annals of Surgery 29:2 (February, 1899), 137–142. Accessed online at NCBI Web page.

- "A New Operation for Hypospadias," Annals of Surgery 23:4 (April 1896), 378–393. Accessed online at NCBI Web page

- "Strangulated Inguinal Hernia of a Cystic Appendix Vermiformis," American Gynæcological and Obstetrical Journal (March, 1896). Read before the Chicago Gynæcological Society, December 20, 1895. Accessed online at Hathitrust.

- "Tuberculosis of the Sacro-Iliac Joint," Annals of Surgery 8:6 (December, 1888), 401–433. Accessed online at NCBI Web page.

- "Tuberculosis of the Sacro-Iliac Joint (Continued)," Annals of Surgery 9:1 (January, 1889), 35-54. Accessed online at NCBI Web page

- "Tuberculosis of the Sacro-Iliac Joint (Concluded)," Annals of Surgery 9:2 (February, 1889), 115–130. Accessed online at pageNCBI Web page

Theosophical writings

Dr. Van Hook served as editor of The Theosophic Messenger and contributed many of its articles and poems, mostly anonymously. He also wrote for The Messenger, The Theosophist, Le Lotus Bleu, The Adyar Bulletin, and other Theosophical journals. The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists articles under the names Weller Van Hook and WV-H.

Through the Rajput Press, he published these books and pamphlets:

- A Primer of Theosophy: A Very Condensed Outline. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1909. Available at Internet Archive and another Internet Archive version. Complimentary copies were sent to major university libraries including Harvard and Princeton. At least 20,000 were printed. 132 p.

- The Principles of Education. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1911.

- Correspondences Between the Planes. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1914. 18 p.

- Voyages. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1925.

- The Cultural System. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1925.

- The Future Way. Chicago: Rajput Press, 1928. Note: First edition was published January 1, 1928.

The Theosophical Publishing House in Adyar published these:

- Correspondences Between the Planes and Some Lessons to Be Drawn from Them. Theosophical Publishing House, 1913. Adyar Pamphlet Number 28. Available from the Canadian Theosophical Association.

Dr. Van Hook also wrote a play, "The Promise of Christ's Return" that was performed at the 1920 convention of the Australian Section. "It was much appreciated by a very large audience."[29]

Additional resources

- Hook, Weller Van in Theosophy World.

Notes

- ↑ Chauncey C. Maher, A Man of Good Will, Chicago Literary Club Papers Online Web page accessed April 9, 2012 at Chilit.org. See page 2-3. On November 6, 2019 it was accessed at another Chilit.org page.

- ↑ Maher, page 3-4.

- ↑ Maher, page 5.

- ↑ Maher, page 6.

- ↑ Maher, page 8.

- ↑ Leslie B. Arey, Appendix to Northwestern University Medical School 1859-1979, Galter Health Sciences Library Web page accessed April 9, 2012 at [1]. See pages 537 and 544.

- ↑ Leslie B. Arey, Northwestern University Medical School 1859-1979, Galter Health Sciences Library Web page accessed April 9, 2012 at [2]. See page 159.

- ↑ The Book of Chicagoans: a Biographical Dictionary (Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Co., 1911), 686.

- ↑ The Book of Chicagoans: a Biographical Dictionary (Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Co., 1911), 686.

- ↑ Maher, page 4.

- ↑ Clara Codd, So Rich a Life (Pretoria: Institute for Theosophical Publicity, 1956), 130.

- ↑ C. J. K., "W.V.H.: A Short Biography," Chicago: Dolan Printing Company, 1935. A copy is available in the TSA Archives in the presidential papers of Weller Van Hook, Records Series 08.02.

- ↑ Maher, page 12-13.

- ↑ Maher, page 12.

- ↑ American Theosophical Society, "Nineteenth Annual Convention Report of Proceedings," September 17-18, 1905. page 29. Records Series 10.08. Conventions and Summer Sessions. TSA Archives.

- ↑ C. Jinarājadāsa, In His Name, Chicago: Rajput Press, 1913. Reprinted in 1923 by The Theosophical Press, Chicago.

- ↑ American Theosophical Society, "Nineteenth Annual Convention Report of Proceedings," September 17-18, 1905. page 3. Records Series 10.08. Conventions and Summer Sessions. TSA Archives.

- ↑ American Theosophical Society, "Twentieth Annual Convention Report of Proceedings," September 16-17, 1906. page 3. Records Series 10.08. Conventions and Summer Sessions. TSA Archives.

- ↑ C. J. K., "W.V.H.: A Short Biography," Chicago: Dolan Printing Company, 1935.

- ↑ C. J. K., "W.V.H.: A Short Biography," Chicago: Dolan Printing Company, 1935.

- ↑ "Weller Van Hook," County Historian Web page, accessed at [3]

- ↑ C. J. K., "W.V.H.: A Short Biography," Chicago: Dolan Printing Company, 1935.

- ↑ C. J. K., "W.V.H.: A Short Biography," Chicago: Dolan Printing Company, 1935.

- ↑ Maher, page 22.

- ↑ Maher, page 23-24.

- ↑ "Dr. Weller Van Hook" The American Theosophist 21.8 Aug 1933 p191.

- ↑ "Dr. Weller Van Hook" The American Theosophist 22.6 (June, 1934), 144.

- ↑ "Van Hook, Weller" The Book of Chicagoans, 1911. Accessed online at Hathitrust.

- ↑ C. W. Leadbeater letter to Fritz Kunz. April 17, 1920. Kunz Family Collection. Records Series 25.01. Theosophical Society in America Archives.