Manly Palmer Hall: Difference between revisions

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

[[File: Manly_P._Hall_three.jpg|230px|right]] | [[File: Manly_P._Hall_three.jpg|230px|right]] | ||

Manly P. Hall was 6 foot 4 tall and had blue-grey eyes. He was charismatic, arrogant, humorous, and scholarly.<ref>Beskin, [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO2tXOLef18 Manly Hall, the Murdered Mystic].</ref> He | Manly P. Hall was 6 foot 4 tall and had blue-grey eyes. He was charismatic, arrogant, humorous, and scholarly.<ref>Beskin, [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dO2tXOLef18 Manly Hall, the Murdered Mystic].</ref> He saw himself not as a scholar, who seeks knowledge for its own sake and the satisfaction of his own mind, but as a teacher who learns in order to bestow his students with knowledge and insights. He deeply believed in the value of the testimonies of Plato, Buddha, St. Paul, and the pagan martyr [[Hypatia]] as medicine for the dark side of scientific progress and materialism: pollution, congestion, crime, selfishness, stress, and steady erosion of ethical and moral standards.<ref>Sahagun, 4.</ref> He gathered many acolytes and received millions of donations, much of it from a mother and daughter belonging to the Lloyd family, an oil dynasty of Ventura County.<ref>Sahagun, 8.</ref> | ||

However there was a glaring dissonance between Halls’ public image and his private reality. He delegated his business affairs to amateurs and took many of his medical problems to healers with questionable credentials. Although he did not have a university degree, he did not correct those who addressed him as Dr. Hall. He advised against trying to develop occult powers yet dazzled starry-eyed followers with demonstrations of his alleged mind reading and predictions of future events.<ref>Sahagun, 71.</ref> For much of his life he binged on cheap sweets, avoided physical activity, and cultivated relationships with followers by telling them, for example, that they had been close friends in a past life.<ref>Sahagun, 11.</ref> | |||

For all his emphasis on the practicality of ancient wisdom, Hall’s life in some respect, was a case in point of a truth not found in his writings. A person can accumulate the “wisdom of the ages” with none of it penetrating one’s self. That perplexity of human nature, a puzzle at the heart of all ethical philosophies, seems never to have occurred to him. <ref>Horowitz, 160-161.</ref> | For all his emphasis on the practicality of ancient wisdom, Hall’s life in some respect, was a case in point of a truth not found in his writings. A person can accumulate the “wisdom of the ages” with none of it penetrating one’s self. That perplexity of human nature, a puzzle at the heart of all ethical philosophies, seems never to have occurred to him. <ref>Horowitz, 160-161.</ref> | ||

None of this should not overshadow the significance of his early masterwork. '''''The Secret Teachings of all Ages''''' remains an indisputable classic and the '''PRS''' remains a vital center for metaphysical investigation and has received academic accreditation.<ref>Lachman, 99-100.</ref> | |||

== Writings == | == Writings == | ||

Revision as of 02:23, 12 July 2021

Manly Palmer Hall (March 18, 1901 – August 29, 1990) was a Canadian-born mystic, eclectic philosopher and founder of the Philosophical Research Society, a modern equivalent of the school of Pythagoras. [1] He was the 20th century’s most prolific writer on mysticism, magic, and ancient philosophies. He authored more than 200 books and gave more than 8000 lectures, most of them weekly at the headquarters of the Philosophical Research Institute.

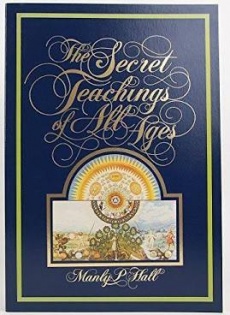

Hall is best known for his 1928 work The Secret Teachings of All Ages. Hall published his magnum opus, an introduction to ancient symbols and secret traditions, at the age of 27, to immediate acclaim. It is the most important book of the early twentieth-century American occult revival and remains influential to this day. [2]

Early life

Manly Hall was born on March 18, 1901 in the rural city of Peterborough, Ontario. His father was a dentist and his mother was a chiropractor. Hall’s parents had separated while his mother was still pregnant with him, and he soon came into the care of his maternal grandmother, Florence Palmer. When he was two years old, she brought him to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where they lived for several years. He was a sickly child, got little schooling but read voraciously on his own. There was a spark of some indefinable brilliance in the youth, which his grandmother nurtured on trips to museums in Chicago and New York.

For a time, the two of them lived in the high-end hotel Palmer House in Chicago where Hall was mostly in the company of grown-ups, including a traditionally garbed Hindu maitre d’hotel, who taught him adult etiquette. Later on, the bookish adolescent was enrolled in a military school.

His grandmother died when he was sixteen and he traveled to California to be with his mother. [3]

Lectures and teaching

Hall’s career as a mystic sage began in 1919, when he came to California to be reunited with his mother. [4] He came under the influence of self-styled followers of Rosicrucianism in Oceanside, California. He lived at the Rosicrucian Fellowship founded by Max Heindel but grew suspicious of the order’s claims to ancient wisdom and soon moved to Los Angeles. There he fell in with metaphysical seekers and discussion groups. [5] One day young Manly Hall was attracted by a sign advertising phrenology, the discipline that reads human psychology through the shape and contours of the skull. The proprietor of the shop, Sydney J. Brownson, quickly became Halls’ guru and explained magnetism, reincarnation, the aura, the wisdom of the ancients, the mysteries of India and the East and the secret teachings of the church to Hall, who proved to be an excellent student with a photographic memory and a talent for speaking. One year later Brownson invited Hall to speak to a select audience who met weekly in a room above a bank and he was a success. [6]

Part showman, part shaman, Hall wore a dark tailored suit and sat mid-stage, his hands resting palms down on the arms of a baronial chair that was bathed in light. He spoke for 1 ½ hours – not a minute longer. Whether his subject was Egyptian initiation ceremonies or mythic water sprites, he concluded abruptly with the same sign-off: “Well, that’s about all for today folks.“[7]

Theosophical Society connections

Hall was influenced by the Theosophical teachings. Joscelyn Godwin wrote:

Apart from a short spell at a military school, he was without formal education. In California he came under the influence of the Theosophical Society. He began his public career in 1920 in Santa Monica, giving a series of lectures on reincarnation. He became a lifelong admirer of H. P. Blavatsky and her Secret Doctrine.[8]

Manly Hall was never a member of the Theosophical Society in America, and possibly never a member of any Theosophical Society. Nonetheless, he was heavily engaged with the TSA and lectured at the Besant Hollywood Lodge, San Francisco, Portland, Chicago, and Oakland. The Theosophical Press distributed [9] and reviewed [10][11]his books, and members studied them in lodge meetings and listened to his lectures on recordings. His Philosophical Research Society also hosted Theosophical lecturers.

Manly Hall was a bit fanatical about anything relating to Helena Petrovna Blavatsky [H.P.B.] He was tremendously earnest about his particular view of Theosophy.[12]He said that the original work of H.P.B. stands more or less unique even within the field of related literature, that her own particular insight makes her works unique, remarkable and valuable. He further said that many of the remarks which she made during her time, which were highly controversial, are now generally accepted and that many of the findings which she reported and which amazed her contemporaries, now belong to our common knowledge.[13]

When Boris de Zirkoff assumed the role as editor of Blavatsky's complete works after World War II, he worked with Hall to publish the fifth volume at the Philosophical Research Society in 1950. Subsequent volumes VI-XV were published through the Theosophical Publishing House in Adyar, India and Wheaton, Illinois, and the PRS helped with distribution. Boris de Zirkoff conducted a long correspondence with Manly Hall.[14]

The Secret Teachings of All Ages

Hall’s world travels in the early 1920s gave him some degree of proximity to the monuments and philosophies of antiquity. But the materials that finally made it possible for him to complete his book of wisdom were those he discovered in the great Western libraries just opening to widespread public use. Through the influence of benefactors, Hall gained access to some of the rarest manuscripts at the British Museum and while living in New York in the mid-1920s, he found material in the vast beaux arts reading room of the New York Public Library. He amassed a bibliography of nearly one thousand entries.

By mid-1928, having presold subscriptions for almost a thousand copies and printing 1,200 more, he published what would become known as the “Big Book” and it has never gone out of print since. [15] The Secret Teachings of All Ages, funded by a bevy of wealthy supporters was published to immediate acclaim. Hall published other books widely considered classics of occult literature, but the Secret Teachings of All Ages stands head and shoulders above the rest. It is the most important book of the early twentieth-century American occult revival, it remains influential, and many of the teachings and ideas it presented to the public remain in circulation. [16][17]

The book is magnificently illustrated with 54 original full-color plates of ancient and medieval emblems and figures by noted illustrator J. Augustus Knapp and 200 black-white illustrations borrowed from rare occult works. The instant success of the book catapulted Hall into the national spotlight. [18]It was the only serious, comprehensive codex of its era that took the world of myth and symbol on its own terms. Hall peered into sources that many historians refused to consider – from Masonic and Rosicrucian tracts to alchemical and astrological works – and recent scholarship has justified some of his historic conclusions. While The Secret Teachings of All Ages has always been ignored within academia, it influenced some who chose more traditional scholarly paths than Hall’s. He clarified ancient ideas that could otherwise seem beyond reach, writing not as a distant judge but as a lover of the rites and mysteries embodied in the old ways.[19]

Philosophical Research Society (PRS)

It upset Hall that esoteric and occult teachings had no place in American universities and he decided to establish a spiritual center in Los Angeles of his own design and purpose with the mission to teach the “practical idealism” preserved in over 100,000 of the wonder-texts of antiquity, develop programs for the good of society, and excite his students' desire to put them to work in everyday life.

On November 20, 1934, Hall’s nonprofit Philosophical Research Society bought a prime piece of real estate overlooking Los Feliz Boulevard and the hills leading to Griffith Park from Capitol Holding Company. On October 17, 1935, about 100 people assembled to break ground for their new headquarters.[20]

PRS provided a cloistered setting where Hall spent the rest of his life teaching, writing, and assembling a remarkable collection of antique texts and devotional objects. His small campus eventually grew to include a fifty-thousand-volume library, a three-hundred-seat auditorium, a bookstore, a warehouse, an office, and a courtyard. It became one of the most popular destinations in Los Angeles for the spiritually curious.

After Hall’s death the campus barely survived simultaneous legal battles – one with Hall’s widow, who claimed it owed her money, and another with the eccentric con artist Fritz, who had befriended the ailing octogenarian to pilfer his antiques and assets in the estimation of a civil-court judge. Hall had signed over his estate to this shadowy “trustee”” just six days before his passing.[21]

The financial damage from these difficult years was irreversible. Following a protracted court battle the nonprofit organization faced a $2 million legal debt, but the control was turned over to a group of longtime supporters. They were forced to sell of many cherished items to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and European collectors.[22]

The PRS did regain fiscal health beginning in 1993 and continued to print different editions of the “Great Book.” [23] PRS now offers a full calendar of lectures, online courses, workshops, wellness classes, concerts, and special events to the general public.[24]

A Private World

Hall wrote scores of books, pamphlets and articles, and gave numerous lectures, typically without notes. Yet, for all his output, Hall remained a riddle to those around him. Following his Sunday morning lectures at PRS, he would promptly exit the auditorium from a side door, enter a car, and be driven back to his nearby house.

Unlike many spiritual teachers who flocked to Hollywood, Hall showed relatively little interest in attracting publicity or hobnobbing with movie stars and he rarely involved himself in movie business. [25]Over the years, however, Hall had many devotees and these included actors and actresses such as Bela Lugosi, Glenn Ford, Burl Ives [a Theosophist], and Gloria Swanson; Hollywood bigwigs such as Sid Grauman, Cecil B. DeMille, and Samuel Goldwyn; scientists such as Luther Burbank, other notables such as Elvis Presley and the astronaut and founder of the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS) Edgar Mitchell, as well as politicians such as Harry S. Truman and Ronald Reagan.[26] [27]

Hall was married in 1930 to his secretary Fay B. Ravenne, an attractive astrologer from Texas. The marriage soon proved to be difficult because Fay was subject to several illnesses and she resented her husband’s growing fame and success. Hall himself suffered from numerous ailments, and overate as his only relief from the misery of married life. Fay retreated deeper into depression and committed suicide in 1941, gassing herself in her car. Hall was devastated but after a short period of mourning he purged all records of Fay from his files and never mentioned her again.

His second wife was Marie Bauer, a petite German immigrant and mother of two. She was sure that Sir Francis Bacon had traveled to America and while there buried a vault with a fortune of gold beneath a church tower in Williamsburg, Virginia. She was convinced that God had chosen her to uncover this vault and her passion proved powerful enough to convince authorities to permit her to dig up the vault, but nothing was found. Marie didn’t give up and her obsession with Bacon’s vault continued for the rest of her life. She had frequent hallucinations, fits of violence, grandiose claims and was at least occasionally psychotic.[28]

The Mystic in Decline

By the late 1970s, sickness had become a way of life for Hall, who was nearing 80. His gall bladder problems had gotten so bad that he stopped lecturing outside of Los Angeles; the organ was removed in 1972. His thyroid glands had been removed when he was young, which might have contributed to his obesity. His eyesight was so poor that he could barely get through the daily mail. His joints ached with arthritis. His days were spent visiting one doctor after another, and stocking his shelves with prescriptions and supplements.[29][30]

In the late 1980s, Hall appeared to lose his personal judgement. He turned over all of his household and business affairs, and even his and PRS’s financial assets, to a self-professed shamanic healer and supposed reincarnate from Atlantis named Daniel Fritz. Hall disregarded anyone who questioned the relationship.

Ill and dangerously overweight in his final years, Hall had apparently bought into Fritz’ claims as a mystical healer and his promise to spread Hall’s work across the world. Hall did drop weight through diet and exercise, and Fritz administered regularly colonics. Hall signed his estate over to Fritz less than a week before his death.[31]The circumstances of Hall’s death were more than suspicious. An autopsy revealed several bruises, smudges of soil, and evidence of trauma, and some called it murder. [32][33] There were charges but they were never pursued and after Fritz’ death in 2001 and his son’s passing in 2003 the file was closed. [34]

Manly P. Hall died on August 29, 1990. A Masonic memorial service dedicated to “The Illustrious Manly Palmer Hall, 33 degree, Grand Cross of Honor, was held on September 23rd, 1990.[35]

Assessment

Manly P. Hall was 6 foot 4 tall and had blue-grey eyes. He was charismatic, arrogant, humorous, and scholarly.[36] He saw himself not as a scholar, who seeks knowledge for its own sake and the satisfaction of his own mind, but as a teacher who learns in order to bestow his students with knowledge and insights. He deeply believed in the value of the testimonies of Plato, Buddha, St. Paul, and the pagan martyr Hypatia as medicine for the dark side of scientific progress and materialism: pollution, congestion, crime, selfishness, stress, and steady erosion of ethical and moral standards.[37] He gathered many acolytes and received millions of donations, much of it from a mother and daughter belonging to the Lloyd family, an oil dynasty of Ventura County.[38]

However there was a glaring dissonance between Halls’ public image and his private reality. He delegated his business affairs to amateurs and took many of his medical problems to healers with questionable credentials. Although he did not have a university degree, he did not correct those who addressed him as Dr. Hall. He advised against trying to develop occult powers yet dazzled starry-eyed followers with demonstrations of his alleged mind reading and predictions of future events.[39] For much of his life he binged on cheap sweets, avoided physical activity, and cultivated relationships with followers by telling them, for example, that they had been close friends in a past life.[40]

For all his emphasis on the practicality of ancient wisdom, Hall’s life in some respect, was a case in point of a truth not found in his writings. A person can accumulate the “wisdom of the ages” with none of it penetrating one’s self. That perplexity of human nature, a puzzle at the heart of all ethical philosophies, seems never to have occurred to him. [41]

None of this should not overshadow the significance of his early masterwork. The Secret Teachings of all Ages remains an indisputable classic and the PRS remains a vital center for metaphysical investigation and has received academic accreditation.[42]

Writings

The Secret Teachings of All Ages, known at first as Encyclopedia of Symbolical Philosophy, was Hall's master work, but in addition to this, he left a large body of books, essays, pamphlets, and articles. The Philosophical Research Society provides a catalog of his works on its website.

Periodicals

Hall published The All-Seeing Eye, a monthly periodical, from May 1923 to September 1931 with a gap 1928-1930. There is an index to the articles on the ManlyPHall.info website. Issues of The All-Seeing Eye are available in digital format:

- Scattered issues at ManlyPHall.info website.

- Volume 2, number 1, November, 1923 at RealityChange.net.

- Volume 5, 1930-31 at IAPSOP website.

He also wrote for other journals. The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 59 articles by or about Manly P. Hall.

Books and pamphlets

Here is a selection of books and pamphlets in chronological order. Many have been released in multiple editions and printings, and are still under copyright. If not noted otherwise, they were published by the Philosophical Research Society.

- The Initiates of the Flame. Los Angeles, 1922. The first published book by Hall. Available at Google Books and Hathitrust.

- The Lost Keys Of Freemasonry. New York: Macoy, 1923. Available at Internet Archive.

- Unseen Forces: Nature Spirits, Thought Forms, Ghosts and Specters, the Dweller on the Threshold, being a series of manuscript lectures compiled in booklet form. Los Angeles: Hall Publishing Co., 1924. Many editions and reprints. Available at Google Books.

- Lectures in Ancient Philosophy: An Introduction to Practical Ideals.

- The Secret Teachings of All Ages. 1928. Available at CIA.gov and Internet Archive.

- Shadow Forms. Los Angeles: Hall Publishing Co., 1928. "Tales of ceremonial magic, of uncanny intuition... full of thrills and of thought-provoking situations."[43] Available at Hathitrust and Google Books.

- Essay on the Fundamental Principles of Occultism. 1929.

- Lectures on Ancient Philosophy—An Introduction to the Study and Application of Rational Procedure. 1929.

- The Mystery of Electricity. Los Angeles: Hall Publishing, 1930. Pamphlet.

- Right Thinking: the Royal Road to Health. Los Angeles: Hall Publishing, 1930. Pamphlet.

- Super Faculties and Their Culture. 1934. Available at Internet Archive.

- The Most Holy Trinosophia of the Comte de Saint-Germain. 1936 (Second edition). Available at Hathitrust.

- Man: the Grand Symbol of the Mysteries. Los Angeles: The Philosophers Press, 1937. Available at Internet Archive.

- Self-Unfoldment by Disciplines of Realization. 1942. Available at Internet Archive.

- The Judgment of the Soul and The Mystery of Coming Forth by Day. Pamphlet. A study in Egyptian metaphysics.

- How to Understand Your Bible. 1943.

- Lady of Dreams: A fable in the manner of the Chinese. Los Angeles, 1943.

- The Guru, by His Disciple: The Way of the East. New York, Philosophical Library, 1944.

- The Secret Destiny of America. 1944. Available at DocDroid.

- Atlantis: an Interpretation. 1946. Available at Hathitrust.

- Reincarnation: the Cycle of Necessity. 1946. Available at Internet Archive.

- Healing - The Divine Art. 1950. Available at Internet Archive.

- America's Assignment with Destiny. 1951.

- The Mystical Christ. 1951, 1956. Available at Internet Archive.

- The Adepts in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition: Part One, The Light of the Vedas. 1952. Available at Internet Archive.

- The Adepts in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition: Part Two, The Arhats of the Buddhism. 1952.

- The Adepts in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition: Part Three, The Sages of China. 1952.

- The Adepts in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition: Part Four, The Mystics of Islam. 1952.

- The Adepts in the Eastern Esoteric Tradition: Part Five, Venerated Teachers of the Jains, Sikhs, and Parsis.. 1952.

- The Therapeutic Value of Music. 1955.

- The Phoenix: an Illustrated Review of Occultism and Philosophy. 1960.

- Buddhism and Psychotherapy. 1967.

- The Phoenix: An Illustrated Overview of Occultism and Philosophy. 1975 (seventh edition).

- Questions and Answers: Fundamentals of the Esoteric Sciences. 1979. Available at Internet Archive.

- The Blessed Angels: A Monograph. 1980. Available at VDocuments.

- Meditation Symbols In Eastern & Western Mysticism-Mysteries of the Mandala. 1988. Available at Internet Archive.

Introductions and contributions

- Prologue to John H. Manas' Life's Riddle Solved. Pythagorean Society. Prologue is "prose poetry."[44]

- Introduction to Max Heindel's Blavatsky and The Secret Doctrine., 1933.

- Essay "As Democracy Awakens" in Plans for a Post-War World. New York, H.W. Wilson Co., 1942.

- Chapter in Virginia Hanson's anthology on mysticism The Silent Encounter. Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974.

- Contributor to The Rainbow Book by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Berkeley, California: Shambhala Publications, 1975.

Additional resources

Websites

- The Manly P. Hall Archive

- The Manly P. Hall Archive. March 31, 2016. Archived website at Internet Archive via Waybackmachine.

- Manly P. Hall: Resources and Inspirations

- Manly Palmer Hall Natal Horoscope at Khaldea.

- The Manly P. Hall Alchemy Archive: A Brief History of an Occult Collection by Derek Christian Quezada. Essay on Hall's collection of alchemical and occult works.

Archival collections

- Boris de Zirkoff Papers. Records Series 22. Theosophical Society in America Archives.

Notes

- ↑ John Michael Greer, The Occult Book. (New York: Sterling, 2017), 179.

- ↑ Geraldine Beskin, "Manly Hall, the Murdered Mystic". International Theosophical History Conference. September 20 and 21, 2014. Accessed on 12/12/19.

- ↑ Mitch Horowitz, Occult America: The Secret History of How Mysticism Shaped Our Nation. (New York: Random House, Inc., 2009), 150-151.

- ↑ Gary Lachman. Revolutionaries of the Soul. Reflections on Magicians, Philosophers, and Occultists. (Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 2014), 90.

- ↑ Horowitz, 151.

- ↑ Gary Lachman, Revolutionaries of the Soul. Reflections on Magicians, Philosophers, and Occultists (Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 2014), 91.

- ↑ Louis Sahagun, Master of the Mysteries. The Life of Manly Palmer Hall. (Port Townsend, WA: Process Media, 49.

- ↑ Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism Volume 1, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill, 2005), 455.

- ↑ Anonymous advertisement, "An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, and Rosicrucian Symbolic Philosophy by Manly P. Hall" Theosophical Messenger 16.7 (December, 1928), 156.

- ↑ Anonymous book review, "The Secret Destiny of America" The American Theosophist 33.4 (April 1945), 97/

- ↑ Anonymous review, "The Manly P. Hall Book" Theosophical Messenger 15.11 (April 1928), page 247.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Manly P. Hall" The Theosophical Messenger 38.1 (January 1930), 6.

- ↑ Manly P. Hall, "Helena P. Blavatsky and the Secret Doctrine". Blog posting dated December 21, 2014. Accessed on 12/12/19. Audio recording of lecture and written material in tribute website.

- ↑ Boris de Zirkoff Papers. Records Series 22. Theosophical Society in America Archives.

- ↑ Horowitz, 154.

- ↑ Greer, 179.

- ↑ Sahagun, 51.

- ↑ Sahagun, 50-51.

- ↑ Horowitz, 162-163,156.

- ↑ Sahagun, 70.

- ↑ Horowitz, 155-156.

- ↑ Sahagun, 273-274.

- ↑ Horowitz, 155-156.

- ↑ Philosophical Research Society website. Accessed on 12/16/19.

- ↑ Horowitz, 157.

- ↑ Lachman, 89.

- ↑ Mitch Horowitz, "Reagan and the Occult". The Washington Post Blog. May 4, 2010. Accessed on 12/12/19.

- ↑ Lachman, 93-95.

- ↑ Sahagun, 203-205.

- ↑ Beskin, Manly Hall, the Murdered Mystic.

- ↑ Horowitz, 159-160.

- ↑ Sahagun, 269-273.

- ↑ Lachman, 99.

- ↑ Horowitz, 160.

- ↑ Sahagun, 260.

- ↑ Beskin, Manly Hall, the Murdered Mystic.

- ↑ Sahagun, 4.

- ↑ Sahagun, 8.

- ↑ Sahagun, 71.

- ↑ Sahagun, 11.

- ↑ Horowitz, 160-161.

- ↑ Lachman, 99-100.

- ↑ Advertisement in The Theosophical Messenger 15.9 (February 1928), 216.

- ↑ G. A. O. "Book Reviews" The American Theosophist 32.12 (Dec 1944), 289.