Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904-1986) was an Indian Theosophist best known as a dancer and educator, and as wife of George S. Arundale, President of the Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Chennai, India. At the beginning of her career in the Society, she expressed her purpose in these words:

To encourage the living of beautiful lives, of lives so refined and so artistic, so gracious and so compassionate, so true and so noble, so wise and so understanding, that everywhere the beautiful is extolled and ugliness fades away.[1]

Early years

Rukmini Devi was born on February 29, 1904, into a Brahmin family in the city of Madurai, South India. Her father, Sr, A. Nilakanta Sastri of Thiruvisanellur, was an engineer and a respected Sanskrit scholar. His wife, Srimati Seshammal,came from a very cultured family of Thiruvaiyar.[2] They were "strongly influenced by theosophical ideas to which they had been introduced in 1901. When her father retired, he settled in Chennai close to the headquarters of the Theosophical Society.” [3]

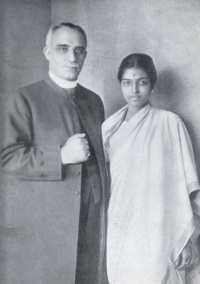

Marriage

On April 27, 1920 the 16-year-old girl married Dr. George S. Arundale, a 44-year-old Englishman who was a Theosophist prominent in Indian education at Central Hindu College. Rukmini wrote of her husband,

"He had a striking personality and had a wonderful sense of humour. He used to come home often and mother developed a great affection for him and would feed him Indian pickles and curries! Dr. Arundale was very handsome and was always surrounded by a group of admirers. He would joke and laugh at everything and I think this was what appealed to my own fun loving temperament. He became so much part of our household that my mother used to call him her Krishna to whom she was a Yasoda. So she did not oppose very strongly when Dr. Arundale proposed marriage. She knew enough about the society and the attitude of her own family whom she knew would be totally against it but she did give her blessings and I did not need anything more. Father had passed away but our links with the Theosophical Society was so strong that my mother sought only the advice of Dr. Besant for whom she had a great reverence."[4]

The ceremony was conducted by Alladi Mahadeva Shastri.[5] Rukmini Devi "was the first well-known Brahmin lady to break caste by marring a foreigner."[6] She and her family were ostracized by their Brahmin associates, but with support of Theosophists, the Indian public eventually adjusted to the marriage.

Theosophical Society

Rukmini joined the Society shortly after her marriage, in June, 1920. In 1923, she became the President of the All India Federation of Young Theosophists, and in 1925 the President of the World Federation of Young Theosophists. She and her husband particularly shared interest in young people and in education.

As wife of George Arundale, Rukmini Devi would have been notable in the Theosophical Society even if she had not been such a strong and unique person in her own right. He was active in the Society for the Promotion of National Education and in political activities, in addition to his many TS activities. In 1926, he became General Secretary of the Australian Section, and in 1928 took up the same role in India. Rukmini accompanied her husband on many of his lecture tours around the world, and was acclaimed as a speaker and dancer everywhere. They traveled to the United States to dedicate the new headquarters building in 1927, and returned in 1929 for the Third World Congress in Chicago, when they were listed among the speakers. Both became members of the American Theosophical Society on September 5, 1929, and when the Olcott-Wheaton Lodge formed on October 6, 1932, they were recorded as charter members, along with Josephine Ransom, Geoffrey Hodson, and Mrs. Hodson.[7]

The Arundales became involved with the International Theosophical Centre in Naarden, The Netherlands:

In 1930, Dr. Arundale became the Head of the [International Theosophical] Centre at Naarden in the Netherlands, and remained so until 1934, when he became President of the Theosophical Society. Rukmini Devi succeeded him and was the Head of the Centre till she passed away in 1986. Although her chief activities were in India in the fields of art, education and animal welfare, she visited the Centre as often as she could, which was usually once a year. Rukmini Devi always took a broad view of theosophy in which the arts, animal welfare and vegetarianism were integrated in theosophy.[8]

Dr. Arundale assumed the Presidency late in 1933, and continued in this role until his death in 1945. Rukmini was only 39 years old when he died. For many years, she served as a member of the General Council, international governing body of the Theosophical Society, and from time to time on the Society's Executive Committee. She was frequently invited to lecture around the world, such as in 1952 when she was guest of honor at the annual convention of the Theosophical Society in America and went on to tour across the country. That year she was also invited to open the new lodge premises at Saigon, Vietnam.[9]

When Mr. Jinarājadāsa, suffering from ill health, retired from the Presidency in 1953, Rukmini Devi received sixteen nominations as a candidate to succeed him. That put her in the position of running against her brother, Nilakanta Sri Ram, who eventually won the election.[10]

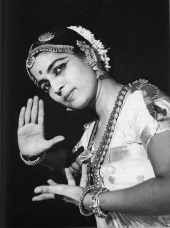

Introduction to dance

During a 1929 ocean journey to Australia, the Arundales met Anna Pavlova, the great Russian ballerina, and struck up a friendship. Pavlova taught Rukmini ballet movements, and encouraged her to dance, not only in ballet, but in the classical tradition of India. Rukmini Devi became interested in a dance, the “Sadir attam,” that was performed by a class of dancing girls who were widely viewed as disreputable. She could see beyond the tacky costumes and vulgarity of the dance to its inner beauty. Since women of her caste were never permitted to associate with the dancers, it took considerable effort for her to find someone who could teach her - Guru Sri Pandanainallur Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai.[11] She did succeed in learning the movements, and refined the dance, bringing it closer to its original artistic form under the name "Bharathanatyam." "She was solely responsible for lifting this art to great heights, and making it well known all over India. It was because of her that people in the North came to know that there was such a thing as a Temple dance."[12]

Her first public performance was at the Diamond Jubilee Convention of the Theosophical Society in 1935. She wrote, "At the Diamond Jubilee Convention we had expected about two hundred people but two thousand turned up. There was so much excitement. More than anything, it totally changed people's prejudice towards the dance."[13] She continued: "Dr. Arundale himself thought at first it was a delightful hobby but when he saw me dance during that Diamond Jubilee Convention in 1935, he was greatly moved. He told me later it was a spiritual experience like a meditation. He and Dr. Cousins were convinced that it was a spiritual medium which could be part of the Theosophical work."[14] Clara Codd wrote of the performance, "You cannot imagine the supreme beauty of those thrilling dances and their dancer. I could have gazed forever. She had a dress copied from an old Rajput picture and at the side of the platform sat a row of Indian musicians. It was an experience of tremendous beauty."[15]

Thereafter Rukmini was much in demand to demonstrate and teach her art. She toured many countries and lectured about Indian arts, and she or her students would perform. She was often accompanied in her travels by a secretary, Margot Paul or Joseph Ross.

Kalakshetra

In January 1936, the Arundales founded the International Academy of the Arts, now known as Kalakshetra, which literally means a holy place of arts. The name Kalakshetra was suggested by Pandit S. Subramania Sastri, a Sanskrit scholar and member of the academy. The school was established, in the words of Rukmini Devi, "with the sole purpose of resuscitating in modern India recognition of the priceless artistic traditions of our country and of imparting to the young the true spirit of Art, devoid of vulgarity and commercialism."

She developed dances representing the Ramayana and other classical texts of India, bringing forth their spiritual concepts. She was particularly imaginative in her characterization of non-human beings such as Hanuman.[16] Every detail was scrupulously researched, to achieve a sense of authentic Indian culture. Costumes, stage settings, language, and music all received her attention. Students were trained in appreciation of all forms of art. Radha Burnier was the first graduate of the school, and Sarada Hoffman was the second.[17]

In 1993, an Act of the Indian Parliament recognised the Kalakshetra Foundation as an Institution of National Importance.

World-Mother

In much the same way that Jiddu Krishnamurti was proclaimed to be the World Teacher by Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, Rukmini was proposed for the role of World-Mother. She wrote in a Foreword to Joseph E. Ross's book Spirit of Womanhood:

The name, 'World-Mother,' was new to me when I first heard those words in 1925. I did not realize that such a a Personage was worshipped in the West and did not understand the significance from the Western point of view. It is natural for me and many millions of Indians to worship the Goddess known in Sanskrit as Jagadamba - literally meaning 'Mother of the World.'[18]

She went on to explain that the feminine spiritual quality is recognized in all women in India, so that even the humblest woman is addressed by strangers as "Mataji" or "Amma," meaning "mother." "Spiritual beauty is embodied in the ideal of the mother, and beyond, by the World-Mother.[19]

C. Jinarajadasa wrote of the term "World-Mother" as "an official of the Great Hierarchy, a devi or goddess or angel, whose function is to represent certain embodiments of the feminine aspect of the dual nature of the Divine."[20] A group within the Theosophical Society's Esoteric Section attempted in the 1920s to create an organization supporting rituals bringing forth the priestly qualities of women. "The first woman to be completely devoted to this work was the late Dr. Mary Rocke, who actually created a ritual of worship by women who were to dedicate themselves to the ideals presented to them by the Holy Mother. As Dr. Rocke could not herself for many reasons undertake the work of creating an organization, it was undertaken by an English lady, [Lady Emily Lutyens ] then in Australia. But this member slowly lost interest in the work. The work was then passed on to another lady, [Rukmini Devi Arundale] who undertook the responsibility, but who also similarly lost interest in it."[21]

Rukmini Devi, then only 21 years old, did not feel the inspiration to establish the League for Motherhood that Dr. Besant, Charles Leadbeater, and C. Jinarajadasa envisioned. She was later quoted as saying to Raja [Jinarajadasa], "if I start an organization it will go dead if it is only my ideas instead of an inspired thing. I can't do it."[22] Her husband fully supported her in this matter, recognizing her potential to have more influence in other types of activities.

Political activities

From 1952 to 1962, Rukmini was a member of the Upper House, or Rajya Sabha, of the Indian Parliament. She was instrumental in passing the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act of 1960. "The Bill caused a great sensation in Parliament and was claimed as representing the best ideals of the Dharmic thought of India."[23] In March, 1962, the Animal Welfare Board of India was established by the government with Mrs. Arundale as Chairman. She remained in that position almost continuously until her death in 1986.[24]

She was well acquainted with Indian Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi, Morarji Desai, and Rajiv Gandhi. Mr. Desai offered three times to nominate her for the post of President of India in 1977, but she declined, preferring to continue with her many other responsibilities.[25]

Views of education

Rukmini was keenly interested in education and in young people generally. In addition to her Kalakshetra academy of dance, she and her husband supported many schools in India. She came to know Dr. Maria Montessori quite well during the decade that the educator lived at Adyar. "If we are true to the spirit of real education, we must make it creative."[26]

Crafts Council of India

From 1975 to 1986, Rukmini served as President of the Crafts Council of India, a nonprofit organization supporting the education of young people in traditional Indian crafts such as stone carving, pottery, and textiles. Her many other commitments prevented her from participating in the day-to-day operations of the organization, but she provided guidance, advice, and encouragement.[27]

Animal welfare work

According to the Theosophical Order of Service:

Rukmini Devi was committed to improving the welfare of animals in India and worked tirelessly to promote an awareness of the sanctity of all life. She wrote and spoke regularly about animal welfare, saying that we need to be the voices of those who cannot speak for themselves.

She was quoted as saying:

We always speak of rights of man and the freedom of the individual, but we forget that besides his rights, man has his responsibilities as well. These responsibilities do not merely extend to the poor and the suffering in the human kingdom, but also to the animal kingdom, which is even more helpless and in need of kindness and compassion. Surely, every living creature has its own right to happiness, and although it is true that there is so much cruelty and sorrow in nature, still there are many compensations and no cruelty in nature can equal that which is perpetrated by man."[28]

In 1968 she was nominated for the Prani Mitra Award in recognition of her services to the Animal Welfare Board of India, of which she was Chairman.[29]

Indian Vegetarian Congress

The Indian Vegetarian Congress was founded by Rukmini in 1959, and she served as President for many years.”[30]

Famous friends and connections

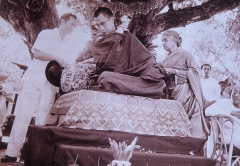

As a well-known public figure herself, Rukmini came to know many celebrities, politicians, and other prominent people, such as Indian Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi, Morarji Desai, and Rajiv Gandhi. She was in Adyar to greet the Dalai Lama when he visited there.

Anna Pavlova was a great influence on Rukmini Devi, who watched her dance numerous times. They became acquainted in Australia in 1926, when Rukmini took her a bowl of chrysanthemums after a performance. "Later on in 1929 Dr. Arundale was sent on Theosophical work to Singapore, Java and Australia and to my delight I found that Anna Pavlova was travelling on the same route. She was dancing in every city we visited and I took different members of the Society with me when I went to her dance. Once we were travelling to Europe on a very fine ship and there she was in a deluxe cabin opposite ours. The entire company was with her as also the hundreds of birds that she kept as pets."[31] The great ballerina encouraged Rukmini to take up ballet instruction with one of her principal dancers, Cleo Nordi, and Rukmini continued ballet practice for several years.

Frequently Rukmini mentioned Dr. Maria Montessori, whom she knew well. "Madame Montessori as a person when she was nearly eighty one, was one of the most youthful human beings I had ever come across. One could easily have said that she was eighty years young. It is the same with many others whom I have seen working with children, because being in the company of children has given them a new outlook, a new experience, so that they are eternally alive and youthful in the right sense of the term."[32] This youthful attitude exemplified Rukmini, as well.

Peter Finch, the famous British actor, was close to Rukmini in his youth. His wife wrote,

When he had been a child, he had been abandoned in Madras in India, in the charge of a grandmother whose sole interest was the Theosophical Society. She lived near a temple, attended meetings with Annie Besant, was a disciple of Krishnamurti.

Peter had been brought there and lived amongst the Buddhist monks. His head was shaven, he was dressed in a saffron robe and daily, went as other monks, did, begging for his food from door to door. Rukmini was then a young woman, living near the temple. She was appalled at his condition, angered at his neglect. She adopted him into her family. She fed him made him wash, and speaking English, undertook his spiritual education. He looked upon her as a mother, attached himself to her and loved her as he had never loved his real mother.[33]

Rukmini Devi wrote of meeting Rafael Kubelik:

"Once when we went from Australia to New Zealand, Kubelik the famous violinist, was travelling on the boat. Everybody was dancing but he was standing in a corner and looking at me fixedly. Finally he summoned up the courage to come over and ask me to dance with him! I told him I did not know how to dance and asked, "Do you?" He said "No." So I said, "Then it's no use trying." His wife was a member of the Theosophical Society and they had both been to Adyar. For such a well known artiste he was strangely childlike.[34]

Awards and honors

India Today includes Rukmini Devi Arundale in the list of "100 People Who Shaped India" that was featured its Millenium Edition. [35] Rukmini was made a Fellow in the Sangeet Natak Akademi, which is the highest honour in the performing arts conferred by the Government of India. She had previously received a monetary award from the Akademi in 1957. The government of Madhya Pradesh awarded her with the Kalidas Samman, a prestigious annual arts prize, in 1984. Indira Gandhi presented the “Desikottama” Award of the Viswabharati University.[36]

In 1968, two honors came her way, presented by the President of India, Dr. Zakir Hussain on February 22 and March 12. Besides the Sangeet Natak Akademi fellowship, she was recognized for her work in the Animal Welfare Board of India with the Prani Mitra Award..[37]

The nation of India has honored her by issuance of commemorative stamps in 1987, shortly after her death, and again in 2009. The 2009 stamp was one of a series of 12 dedicated to India's "Nation Builders."

Honorary doctorates were awarded by Wayne State University in Indiana, U.S.A. in 1960; by Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta, in 1969; by Viswabharati University, Shanthiniketan in 1972; and Benares Hindu University 1982.[38] A Rukmini Devi Medal for Excellence in the Arts has been awarded by by the Centre for Contemporary Culture, New Delhi since 2001.

Another high honor that Rukmini received was the Padma Bhusan Award in 1956 from the government of India. According to national Website, this category of awards is given on Republic Day for exceptional and distinguished service. Nominations from state governments and other units of government are considered by an Awards Committee whose final recommendations are approved by the Home Minister, Prime Minister and President.[39]

A Rukmini Devi Museum has been established at Kalakshetra to display a large number of art objects collected by Rukmini and her brother Yagneswara Shastri, and a collection bequeathed to her by Theosophist James Cousins.[40]

In 1984, the World Vegetarian Congress awarded her The Mankar Trophy to recognize her services to the cause of vegetarianism. She also received numerous awards for her animal welfare work, including Prani Mitra, Friend of All Animals, from the Animal Welfare Board of India, the Queen Victoria Silver Medal from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, London, and was listed on the roll of honour by the World Federation for the Pretection of Animals, The Hague.

In 2016, Rukmini's 112th birthday was celebrated in the Internet with a Google Doodle.

Writings

While Rukmini Devi did not write any full-length books, she produced some excellent pamphlets and over one hundred articles that were published in Theosophical periodicals.

The Teacher and the Pupil was edited by the European Committee of the Besant Cultural Centre and published in Tiruvanmiyur, India. This text focuses on the need for educators to be child-like and to love their students, and on the most important aspects of education: beauty, spirituality, and love.

Theosophical Publishing in Adyar published several of Rukmini's works as pamphlets:

- My Theosophy presents her view of truth and the role of the emotions in conveying the essential teachings of the "Great Teachers."

- The Creative Spirit distinguishes between brilliance and creativity, and discusses how the ordinary person can cultivate creativity through spirituality.

- Art and Education discusses the integration of art with education and life.

- Dance and Music

- Yoga: Art or Science draws parallels between Yoga, Dance, and Music.

- Woman as Artist

- Theosophy as Beauty, written with George S. Arundale and C. Jinarajadasa as Adyar Pamphlet No. 208, published in 1936. It is available online at the Canadian Theosophical Association Web page.

- Message of Beauty to Civilizations, published as No. 212 in the Adyar Pamphlets Series, undated. It is available online at the Canadian Theosophical Association Web page.

Final days

Beginning on December 16, 1985, the Kalakshetra School began six weeks of celebration for its Golden Jubilee. Rukmini Devi was frail, but worked indomitably so that no one knew how ill she was. Her passing on February 24, 1986 came as a great shock. “Crowds had gathered with garlands and wreaths to pay their last respects. The Governor, Ministers of States and other prominent citizens of Madras all came to pay their homage for truly she was a woman whose passing the whole country mourned. As a singular mark of respect, homage was paid to her in the Tamilnadu [state] Assembly which stood in silence.” .[41] The Kalakshetra artists chanted bhajans and prayers continuously.

Funeral rites were simple. A brief Christian memorial service was attended by close family and friends at Arundale House, conducted by John Clarke. In the Hindu tradition, a 10th Day ceremony was held. It included reading of excerpts from the Taittareya Upanishad and bhajans sung by Sridevi Mehta. [42]

Additional Resources

Articles

- Arundale, Rukmini Devi in Theosophy World.

Books

- Art and Culture in Indian Life. Trivandrum: Kerala University Press, 1975.

- Arundale, Rukmini Devi. Selections, Some Selected Speeches & Writings of Rukmini Devi Arundale. Chennai: Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003.

- Gupta, Indra.India’s 50 Most Illustrious Women. Icon Publications, 2003. ISBN 81-88086-19-3.

- Kothari, Sunil. Photo Biography of Rukmini Devi. Chennai, The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2004.

- Meduri, Avanthi. Rukmini Devi Arundale (1904-1986), A Visionary Architect of Indian Culture and the Performing Arts. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2005. ISBN 81-208-2740-6.

- Nachiappan, C. Rukmini Devi: Bharata Natya. Chennai: Kalakshetra Publications, 2003.

- Nachiappan, C. Rukmini Devi: Dance Drama. Chennai: Kalakshetra Publications, 2003.

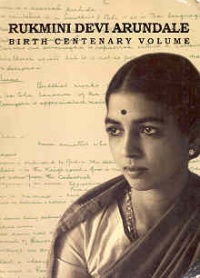

- Ramani, Shakuntala, ed. Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Volume. Chennai: Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003.

- Samson, Leela. Rukmini Devi: A Life. Delhi: Penguin Books, India, 2010. ISBN 067008264.

- Sarada, S. Kalakshetra-Rukmini Devi, Reminiscences. Madras: Kala Mandir Trust, 1985.

- Shraddanjali, Brief Pen Portraits of a Galaxy of Great People Who Laid the Foundations of Kalakshetra. Chennai: Kalakshetra Foundation, 2004.

Websites

- Crafts Council of India Website.

- Indian History of Indian Vegetarian Societies.

- Kalakshetra Website.

Video

- Rukmini Devi Arundale Chose Dance Over Becoming President Of India. Posted February 24, 2020 in MyNation YouTube channel.

- Rukmini Devi Arundale - Bharatanatyam. A Prakash Jha Production, from Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Delhi. Posted on September 8, 2022 on the Classic Dance YouTube channel. Narration is in Hindi. Interviews of Rukmini are interspersed with sequences of Bharatnatyam dancing.

- Smt. Rukmani Devi Arundel's Interview. Interview for Prof.Sudharani Raghupathi's television Program. POsted July 27, 2012 on jayakamala pandiyan YouTube channel. Recorded for VHS in early 1980s.

- Rukmini Devi Arundale: The Bharatnatyam Pioneer. Posted on Mar 10, 2023 in Feminism In India YouTube channel.

- ↑ Anonymous, "Srimati Rukmini Devi Arundale" biographical sketch. Administrative files. Theosophical Society in America.

- ↑ Joseph E. Ross, Spirit of Womanhood, privately published by the author, 2009.

- ↑ Theosophical Order of Service,[html://www.international.theoservice.org/e-news/20/en20-02.html TOS In-Touch.online] No. 20 (February 2012), accessed February 28, 2012.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed.,(Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 15-16.

- ↑ ”Sarada Hoffman,” KutcheriBuzz Website www.kutcheribuzz.com/features/interviews/sarada.asp, accessed February 28, 2012.

- ↑ Ross, vii

- ↑ George Arundale and Rukmini Devi Arundale membership records. Membership Ledger Cards, microfilm roll 1. Theosophical Society in America Archives.

- ↑ Shakuntala Ramani, ed., Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 189.

- ↑ "Administrative Notes" The American Theosophist 40.5 (May, 1952), 83.

- ↑ "News and Notes: From the Recording Secretary," The American Theosophist 40.12 (December, 1952), 238.

- ↑ Shakuntala Ramani, ed., Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 15-16.

- ↑ Ibid., 138.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 46.

- ↑ Ibid., 46.

- ↑ Clara Codd, So Rich a Life (Pretoria: Institute for Theosophical Publicity, 1956), 389-390.

- ↑ Ramani, 171

- ↑ ”Sarada Hoffman,” KutcheriBuzz Website www.kutcheribuzz.com/features/interviews/sarada.asp, accessed February 28, 2012.

- ↑ Ross, ix.

- ↑ Ross, x.

- ↑ Ross, 55.

- ↑ Ross, 53-5.

- ↑ Ross, 67.

- ↑ Shakuntala Ramani, ed., Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 204.

- ↑ Ibid., 205.

- ↑ Ibid., 111.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, The Teacher and the Pupil (Tiruvanmiyur, India : European Committee of the Besant Cultural Centre, 19??), 4.

- ↑ Radha Menon, “Homage to Rukmini Devi,” ’’Kalakshetra News, Golden Jubilee Year: Rukmini Devi Memorial Issue’’(1986), 23.

- ↑ Ramani, 204.

- ↑ "News and Notes," The American Theosophist 56.7 (July, 1968), 167.

- ↑ Indian Vegetarian Congress Website http://www.vegcongress.org/, accessed February 29, 2012.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 26.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, The Teacher and the Pupil (Tiruvanmiyur, India: European Committee of the Besant Cultural Centre, 19??), 4.

- ↑ Tamara Finch, “Unexpected Phone Call,” ‘’Kalakshetra News, Golden Jubilee Year: Rukmini Devi Memorial Issue’’ (1986), 32.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Arundale, "Rukmini on Herself," Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume, Shakuntala Ramani, ed., (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 32.

- ↑ N. Pattabhi Raman, "Rukmini Devi:Czarina of Dance," India Today Millenium Edition (2000), available online at iToday Website [1], accessed March 1, 2012.

- ↑ ’’Kalakshetra News, Golden Jubilee Year: Rukmini Devi Memorial Issue’’(1986), 18.

- ↑ "News and Notes," The American Theosophist 56.7 (July, 1968), 167.

- ↑ Lakshmi Venkatraman, ed.,"It All Began," Rukmini Devi Bharata Natya (Chennai: Kalakshetra Publications, 2003), 34.

- ↑ "Padma Awards," National Portal of India, My India My Pride Web page [2], accessed March 2, 2012.

- ↑ Rukmini Devi Museum Website http://www.kalakshetra.net/rukminidevi_museum.html.

- ↑ Shakuntala Ramani, "O Shining Light," Kalakshetra News, Golden Jubilee Year: Rukmini Devi Memorial Issue (1986), 11.

- ↑ ibid, 11.