Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin was a Russian pianist and composer who was much influenced by Theosophy.

Early life and education

Musical career

Theosophical Society connections

A young friend the Viscount de Gissac asked Scriabin to lecture and write in French, but the composer declined, claiming that his knowledge of French was insufficient. Studying Theosophical literature in French improved his proficiency, so that eventually Scriabin used French notation in his musical compositions.

In Paris in early 1905, de Gissac gave Scriabin a copy of La Clef de la Théosophie, the French translation of Helena Blavatsky’s book The Key to Theosophy (1889) which Scriabin described in a letter of April/May 1905 as a remarkable book and astonishingly close to his own thinking. From that time on, more and more of Scriabin’s circle of friends were drawn from the French and Belgian branches of the |Theosophical Society, most notably the painter Jean Delville with whom Scriabin became associated when he relocated to Brussels in 1908. It has been suggested that Scriabin enrolled into formal membership of its Belgian branch at this time, and that Delville may have introduced him to the Sons of the Flames of Wisdom, a secret Promethean cult within Theosophy, but solid documentary evidence for this has yet be produced. Both Leonid Sabaneev and Boris Schloezer later recalled that a French translation of Blavatsky’s book The Secret Doctrine (1888) was always on Scriabin’s work table. It was clear that Scriabin had studied La Doctrine Secrète with great care as he had annotated and underlined in pencil what he considered to be the most important passages. Scriabin also subscribed to Le Lotus Bleu, a monthly francophone theosophical journal, during the period 1904–9 inclusive; this observation can help to account for the presence of the expressive French musical directions in Le Divin Poème, Op.43 (1904). Taken altogether, it is clear that Scriabin carefully studied a very considerable amount of theosophical literature in French during 1904–1909 while he was resident outside Russia, and this would undoubtedly have improved his capacity to express his esoteric, occultist and mystical intentions for his music.

... In addition to the two French texts by Blavatsky and the monthly copies of Le Lotus Bleu mentioned above, Scriabin also had French translations of Auguste Barth’s The Religions of India and Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia in his bookcase. Furthermore, from 1911 onwards in Moscow Scriabin subscribed to three theosophical journals including the francophone monthly periodical Revue Théosophique Belge.[1]

Scriabin wrote in May, 1905 to a friend that "La Clef la Théosophie is a remarkable book. You will be astonished at how close it is to my thinking."[2] He began to blend together Theosophical concepts with the native symbolism of the Russian Silver Age artists and writers as he wrote expressive directions for works such as the Preparatory Act of the Mysterium.[3]

[In 1906] Scriabin's conversations were full of theosophy and the personality of Blavatsky. he wanted to return to Russia where Theosophy had even more of a vogue than abroad. Even with the exposure of Blavatsky's occultism, which appeared headlined in every newspaper of the world, Scriabin was "unshaken... He attributed the exposés to personal grievances on the part of one member or other in the Theosophical movement."[4]

Theosophical influence in Prometheus symphony

Prometheus, "The Poem of Fire," Opus 60, was Scriabin's fifth and last symphony, written in 1909-1910. It was scored massively, with prominent piano and chorus, and was planned to be performed with a "color organ," which would project appropriate colors on a screen synchronized with the music.

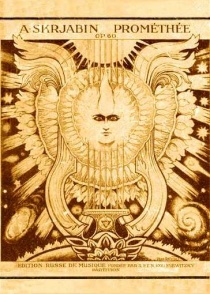

Jean Delville, the Belgian artist whom he met in 1908, had become his friend. Delville, a dedicated Theosophist, designed the cover for the score to the symphony.

He adored the cover design of his Prometheus symphony. It showed a sexless face surrounded by cosmic symbols, nebulae of clouds, spiraling comets, and was drawn by his Belgian friend, Jean Delville (b. 1867), a bachelor, professor of Fine Arts at the Royal Academy, and President of the national Federation of Artists and Sculptors. Looking at that cover of the androgyne or hermaphrodite, Scriabin said, "In those ancient races, male and female were one… the separation into poles hadn't yet taken place.[5]

Biographer Faubion Bowers wrote:

Prometheus as a plot reeks of Theosophical symbolism and is Scriabin's only composition so heavily inflated with such paraphernalia. It exhales Brussels and the dense, mystical air of that city. Delville's cover design for the score shows a lyre ("the World," symbolized by music) rising from a lotus bloom ("the Womb," mind or Asia). In the center over the Star of David is Prometheus's face ("really the ancient symbol of Lucifer," Scriabin said, encompassing all religions). Delville, and perhaps Scriabin, had joined a secret cult within Theosophy called "Sons of the Flames of Wisdom." They worshiped Prometheus, because those fires, colors, lights were metasymbols of man's highest thoughts. Fire was Prometheus's stolen gift to man, and it lay deep within hearts...

To Scriabin, Prometheus had further symbolism beyond Theosophy's haziness. Lucifer was the "Light Bringer," according to the Christian Bible, and Satan was the "Disobedient Rebel." Sabaneeff's program notes... state that "Prometheus, Satanas, and Lucifer all meet in ancient myth. They represent the active energy of the universe, its creative principle. The fire is light, life, struggle, increase, abundance, and thought. At first, this powerful force manifests itself wearily, as languid thirsting for life. Within this lassitude then appears the primordial polarity between soul and matter. Later it does battle and conquers matter - of which it itself is a mere atom - and returns to the original quiet and tranquillity ... thus completing the cycle..."[6]

Later years

On April 2, 1915, Scriabin performed his final recital in St. Petersburg.

Musical compositions

Theosophist Margaret Cousins, a concert pianist, wrote: "His music has constantly in it a most poignant sweet quality which seems to pierce to the holy of holies of one's being."[7]

Scriabin Museum

The Alexander Scriabin Memorial Museum was established on July 17, 1922 to preserve the apartment where the composer lived for his final three years, in an old mansion on Arbat Street in Moscow. The composer's prized possessions were carefully restored, including his copy of The Secret Doctrine.[8] The museum preserves Scriabin's library, letters, sheet music, and other items.

Additional resources

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists articles about Scriabin.

Notes

- ↑ Richard E. Overill, Alexander Scriabin’s Use of French Directions to the Pianist at Scriabin Association web page.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume II (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 52.

- ↑ Richard E. Overill, Alexander Scriabin’s Use of French Directions to the Pianist at Scriabin Association web page.

- ↑ Bowers, Volume II, 117.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume I (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 87.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume II (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 206-207.

- ↑ Margaret Cousins, "Memorabilia of Scriabine - the Master Musician of Theosophy," The Theosophist 56 (November 134), 173.

- ↑ Faubion Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer 1871-1915, Volume I (Tokyo:Kodansha International Ltd, 1969), 87.