Anna Bonus Kingsford: Difference between revisions

Linda Dorr (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Linda Dorr (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Their only child, daughter Eadith, was born in September 1868. Given her many other interests, Anna found the demands of motherhood rather stressful.<ref> ibid., pp. 49-50 </ref> Fortunately for Eadith, the family could afford a “nurse” (now known as a nanny). | Their only child, daughter Eadith, was born in September 1868. Given her many other interests, Anna found the demands of motherhood rather stressful.<ref> ibid., pp. 49-50 </ref> Fortunately for Eadith, the family could afford a “nurse” (now known as a nanny). | ||

English medical schools did not admit women, so Anna entered Paris Medical School in the spring of 1874. Getting a medical education required a great deal of courage and commitment. In addition to being the lone woman in her classes and the stress of much traveling between England and Paris, the practice of vivisection at the school caused her great anguish. Although she refused absolutely to participate in it, and never stopped campaigning against it, her intelligence and hard work ensured her success. By | English medical schools did not admit women, so Anna entered Paris Medical School in the spring of 1874. Getting a medical education required a great deal of courage and commitment. In addition to being the lone woman in her classes and the stress of much traveling between England and Paris, the practice of vivisection at the school caused her great anguish. Although she refused absolutely to participate in it, and never stopped campaigning against it, her intelligence and hard work ensured her success. By the spring of 1880, the only requirement remaining was the presentation of her thesis. | ||

Anna’s thesis was on vegetarianism, and she looked forward to presenting it. However, when she arrived at the hospital at the appointed time, the chief doctor, a Professor Le Fort, “informed her that her thesis could not be received as it stood; not because it was unscientific – its accuracy was unimpeachable in that respect – but because it was moral!”<ref>Maitland, Vol. 1, pp. 366-67</ref> Dr. Le Fort and several of his colleagues had no objections in this regard, but other faculty members did, in particular one who was vehemently opposed to admitting women into medical school and who also did not appreciate Anna’s anti-vivisection stance. As Maitland noted dramatically, “It was a veritable thrust from the spear of Ithuriel, and the hand that had dealt it was a woman’s.”<ref>ibid.</ref> | |||

Dr. Le Fort, however, assured Anna that he himself would edit the offending portions of her thesis. This was done, and on July 22, 1880, Anna presented her thesis to a friendly audience (her faculty adversary apparently did not attend) and was duly awarded her medical degree. The controversy surrounding the original version of her thesis brought attention to it, and together with her skill as a writer resulted in fairly high demand for it. In 1881, with the original sections on ethics restored, it was published in book form with the title ''The Perfect Way in Diet'' (not to be confused with her and Maitland’s later, much longer and better known book entitled ''The Perfect Way; or the Finding of Christ''). | |||

On returning to England, Anna began a small private medical practice and continued her anti-vivisection and pro-vegetarian work. She did a fair amount of public speaking, which at the time was frowned upon for women.<ref>Pert, pp. 95-96</ref> It’s not clear that she spoke much about women’s equality during this time, but her actions very clearly demonstrated her belief in it. | |||

== Theosophical Society involvement == | == Theosophical Society involvement == | ||

Anna’s views coincided with many theosophical teachings. She and Maitland attended some meetings of the Theosophical Society, and some TS members attended her lectures.<ref>Pert, p. 84</ref> Anna Kingsford was admitted to membership in the [[Theosophical Society]] on January 3, 1883, on the same day as her friend [[Edward Maitland]].<ref>Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at [http://tsmembers.org/ http://tsmembers.org/]. See book 1, entry 1583 (website file: 1A/49).</ref> Anna was immediately offered, and accepted, the office of President of the London Lodge. | |||

As is not unusual in any human organization, even (perhaps especially) those that study and teach metaphysics, differences of opinion arose regarding the “truth” of various teachings. <ref>See Pert’s Chapter 13, pp. 127 ff</ref> The upshot in this case was that Anna and Maitland formed the Hermetic Lodge of the Theosophical Society, which was inaugurated in April 1994 and very shortly became the Hermetic Society rather than a branch of the TS.<ref> Pert, pp. 128-130</ref> While both organizations were concerned with honoring spiritual values and esoteric studies, the TS leaned toward an Eastern presentation and the Hermetic Society a Western (largely Christian) one. | |||

== Perspectives on Christianity and Hermeticism == | == Perspectives on Christianity and Hermeticism == | ||

Revision as of 00:09, 7 March 2019

ARTICLE UNDER CONSTRUCTION

ARTICLE UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Anna Mary Kingsford (née Bonus, September 16, 1846 – February 22, 1888) was a prominent English Theosophist in the 1880's, best known as the co-author with Edward Maitland of The Perfect Way.

According to Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett:

Kingsford, Anna Bonus, 1846-88. English author and spiritualist whom with her co-worker, Edward Maitland, promoted a Hermetic approach to Christianity and metaphysics. She is best known for her book The Perfect Way, published in 1882. She was a strict vegetarian and anti-vivisectionist, and KH states that on this account her phenomena were more accurate and reliable than most. He was instrumental in having her elected President of London Lodge. In October 1883, she wrote to HPB sending her photograph and asking that it be forwarded to KH. HPB's reply to her was torn up by M and she complained bitterly about it to APS (LBS, pp. 30, 69, 73). HPB also complained about Mrs. Kingsford's being kept in the Presidency of London Lodge, telling APS that it was due to a request of the Maha Chohan (LBS, pp. 82, 90). HPB sometimes called her the "Divine Anna," and asked Mrs. Sinnett to get a picture of her and sent it to her at Adyar. In 1883, Mrs. Kingsford issued a circular letter to the London Lodge members which was critical of APS's book, Esoteric Buddhism. TSR issued a reply in pamphlet form in January 1884. See biography HPB X: 438-40; ML index.[1]

Personal life

Anna Bonus Kingsford was, to say the least, an extraordinary woman — a mystic, a poet, a feminist, and a scientist as well, she was one of the first women in England to become a medical doctor, although she had to go to Paris to earn her degree. She was known for being an ardent anti-vivisectionist and, not surprisingly, was a vegetarian. She was a prolific writer on the esoteric and the occult, with her long-time friend and collaborator Edward Maitland. A woman of independent means, at the age of 21 she married her distant cousin, Algernon Kingsford, on the condition that she would have the freedom to pursue her own interests.

After Anna’s untimely death, Maitland wrote a biography of her. There is some argument as to how accurate it is, but it does seem likely that Edward Maitland knew her better than most people. A more recent biography by Alan Pert [2], while much less detailed, is thoroughly annotated.

According to Maitland’s biography [3], Anna was the youngest of 12 children, born years after her siblings, and she spent a great deal of time alone as a child. She spent much of her childhood communing with nature -- flowers in particular. Apparently clairvoyant from birth, the very young Annie went through a phase in which she asserted that she was not, in fact, human, but was a native of the fairy realm who had secured human birth in order to fulfill her destiny. [4]

When Annie learned to read she had unlimited access to the family library, and read a great deal of classic mythology and fable. She loved these stories, and rendered them into plays starring her many dolls, improvising and ad libbing with no apparent effort. She was unperturbed by lack of a human audience; if everyone in the family was busy elsewhere, the dolls who weren’t characters in the production became the audience.

Annie learned fairly early to keep quiet about her clairvoyant experiences, since successful predictions of events, especially when she had a premonition of someone’s death, made the adults around her quite uncomfortable. Always a highly sensitive and somewhat frail child, her “seership” was sometimes treated as an abnormal medical condition, to her great dismay. [5] Her physical health was never robust, and she felt injured by these medical treatments (we don’t know exactly what they were).

There was never anything fragile about her attitude, however. Talented in all the arts — including music, drawing, and painting — her great passion was writing poetry and short stories. By the time she was 13, she was being published in Churchman’s Companion magazine. She submitted a story called “Beatrice: A Tale of the Early Christians,” which so impressed the magazine’s publisher that he brought it out as a small book instead. Later he also published a collection of her poems in a book called River Reeds. [6]

Anna was always devout, but never conventional. Her religious experiences were very deep and meaningful to her, and she seems to have trusted her own experience far more than the dictates of organized religion. Hence it is not surprising that she fell in love with her distant cousin by marriage, Algernon Kingsford, who was a theological student and a man very much ahead of his time.

Algernon was decidedly not the man her mother wanted her to marry. Anna had no shortage of suitors, and Mrs. Bonus wished to see her daughter make a conventional match. Unfortunately for her, Anna was never one to crave convention in any area of life. She was 21 and Algernon was 22 when they eloped, on the last day of 1867. Algernon was entirely supportive of Anna’s pursuing her own interests, which were not far removed from his. Anna shared his interest in theology, and she studied with him. Once he had become a minister, she helped compose and revise his sermons, and in turn, Algernon helped supervise the household duties which, at the time, were considered exclusively a woman’s province. [7]

Their only child, daughter Eadith, was born in September 1868. Given her many other interests, Anna found the demands of motherhood rather stressful.[8] Fortunately for Eadith, the family could afford a “nurse” (now known as a nanny).

English medical schools did not admit women, so Anna entered Paris Medical School in the spring of 1874. Getting a medical education required a great deal of courage and commitment. In addition to being the lone woman in her classes and the stress of much traveling between England and Paris, the practice of vivisection at the school caused her great anguish. Although she refused absolutely to participate in it, and never stopped campaigning against it, her intelligence and hard work ensured her success. By the spring of 1880, the only requirement remaining was the presentation of her thesis.

Anna’s thesis was on vegetarianism, and she looked forward to presenting it. However, when she arrived at the hospital at the appointed time, the chief doctor, a Professor Le Fort, “informed her that her thesis could not be received as it stood; not because it was unscientific – its accuracy was unimpeachable in that respect – but because it was moral!”[9] Dr. Le Fort and several of his colleagues had no objections in this regard, but other faculty members did, in particular one who was vehemently opposed to admitting women into medical school and who also did not appreciate Anna’s anti-vivisection stance. As Maitland noted dramatically, “It was a veritable thrust from the spear of Ithuriel, and the hand that had dealt it was a woman’s.”[10]

Dr. Le Fort, however, assured Anna that he himself would edit the offending portions of her thesis. This was done, and on July 22, 1880, Anna presented her thesis to a friendly audience (her faculty adversary apparently did not attend) and was duly awarded her medical degree. The controversy surrounding the original version of her thesis brought attention to it, and together with her skill as a writer resulted in fairly high demand for it. In 1881, with the original sections on ethics restored, it was published in book form with the title The Perfect Way in Diet (not to be confused with her and Maitland’s later, much longer and better known book entitled The Perfect Way; or the Finding of Christ).

On returning to England, Anna began a small private medical practice and continued her anti-vivisection and pro-vegetarian work. She did a fair amount of public speaking, which at the time was frowned upon for women.[11] It’s not clear that she spoke much about women’s equality during this time, but her actions very clearly demonstrated her belief in it.

Theosophical Society involvement

Anna’s views coincided with many theosophical teachings. She and Maitland attended some meetings of the Theosophical Society, and some TS members attended her lectures.[12] Anna Kingsford was admitted to membership in the Theosophical Society on January 3, 1883, on the same day as her friend Edward Maitland.[13] Anna was immediately offered, and accepted, the office of President of the London Lodge.

As is not unusual in any human organization, even (perhaps especially) those that study and teach metaphysics, differences of opinion arose regarding the “truth” of various teachings. [14] The upshot in this case was that Anna and Maitland formed the Hermetic Lodge of the Theosophical Society, which was inaugurated in April 1994 and very shortly became the Hermetic Society rather than a branch of the TS.[15] While both organizations were concerned with honoring spiritual values and esoteric studies, the TS leaned toward an Eastern presentation and the Hermetic Society a Western (largely Christian) one.

Perspectives on Christianity and Hermeticism

In 1884, Dr. Kingsford gave seven lectures that were much later published as The Credo of Christendom. A book review in 1917 regarded her work as a means to transmute Christianity in "finer gold" during the turbulence of World War I:

Christianity is just now in dry dock for repairs; it, with so many other things, is in course of reconstruction through the agency of the War, and unless it receives a fresh influx of life, understanding and application, it will be swept away with other out-of-date organisations. This book will be a most valuable addition to the literature of those who are working through the old Catholic Church for the regeneration of the Christian religion, for it is an illuminating and original compendium of interpretations of Christian and Hermetic beliefs, written in classic style and lit up by the beauty of thought and poetic expression which give such distinction to all Mrs. Kingsford's work...

As the prophetess of the Day of the Woman as human being, Intuition and soul, she holds a unique place in Western religious literature; and in these lectures and articles the truths concerned with the Divine Feminine are clearly enunciated, especially in connection with the doctrines of the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary...

There is some striking and new idea to be found in every page of the work of this most gifted seeress.[16]

,

Writings

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists at least 50 articles by or about Dr. Kingsford.

- The Credo of Christendom. London: John M. Watkins, 1917. This is a compilation of seven lectures delivered in 1884, published posthumously.

- Clothed with the Sun.

- The Perfect Way. Coauthor Edward Maitland.

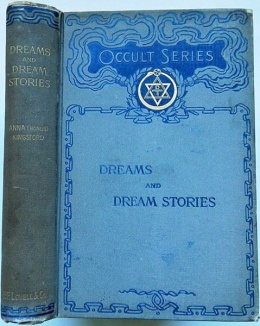

- Dreams and Dream Stories. London: E. F. Lovell & Co., 18xx.

- The Virgin of the World, of Hermes Trismegistus. Ttranslated by Anna Kingsford and Edward Maitland.

Online resources

Articles

- Anna Mary Bonus Kingsford by Paradoxos Alpha

Books

- The Perfect Way by Anna Kingsford

- Dreams and Dream-Stories by Anna Kingsford

- Anna Kingsford, Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists by Edward Maitland

Additional resources

- Anna Kingsford Site

- Anna Kingsford's Natal Chart at Astrodienst

Notes

- ↑ George E. Linton and Virginia Hanson, eds., Readers Guide to The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972), 237.

- ↑ Pert, Alan. Red Cactus: The Life of Anna Kingsford. Watsons Bay, Australia: Books & Writers Network Pty Ltd, 2006.

- ↑ Maitland, Edward: Anna Kingsford — Her Life, Letters, Diary, & Work (Vols. 1 & 2). London: John M. Watkins, 1913. Available online at http://www.humanitarismo.com.br/annakingsford/english/Works_by_Anna_Kingsford_and_Maitland/Texts/013_OAKM-I-MaitLife.htm

- ↑ Maitland, Vol 1, p. 2

- ↑ ibid, p. 3

- ↑ London, 1866: Joseph Masters (Aldersgate Street & New Bond Street), 71 pp. This book is reproduced at http://www.humanitarismo.com.br/annakingsford/english/Works_by_Anna_Kingsford_and_Maitland/Texts/OAKM-I-River.htm

- ↑ Pert, p. 48

- ↑ ibid., pp. 49-50

- ↑ Maitland, Vol. 1, pp. 366-67

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Pert, pp. 95-96

- ↑ Pert, p. 84

- ↑ Theosophical Society General Membership Register, 1875-1942 at http://tsmembers.org/. See book 1, entry 1583 (website file: 1A/49).

- ↑ See Pert’s Chapter 13, pp. 127 ff

- ↑ Pert, pp. 128-130

- ↑ M.E.C. [Margaret Cousins?], "Book-Lore," The Theosophist 28.8 (May, 1917), 228-230.