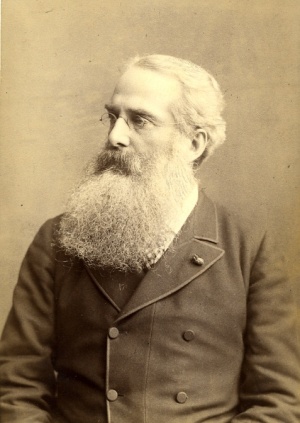

Henry Steel Olcott

Henry Steel Olcott (August 2, 1832 – February 17, 1907) was an agriculturist, American military officer, journalist, lawyer, and co-founder of the Theosophical Society.

He held the title of President-Founder of the Society from 1875 till his death in 1907. He was the first well-known American of European ancestry to make a formal conversion to Buddhism. During his presidency he helped to restore Buddhism in South Asia, and established schools for children of Buddhist and Hindu families, among many other notable achievements.

Col. Olcott related the timeless wisdom of Theosophy to the cultures of both East and West, applied it to everyday life, and built the Society into an international organization.

See also Mahatma Letters to H. S. Olcott and Olcott writings.

"He held the world in his heart." - Josephine Ransom[1]

Early years

Colonel Olcott was a descendant of a family which had settled in America many generations earlier when Thomas Olcott, a Puritan, emigrated from England. His father, Henry Wyckoff Olcott, and his mother, Emily Steel, were both of New York City. He was born in Orange, New Jersey, on August 2, 1832, the eldest of six children. His younger siblings were Isabelle Buloid, Anna Wyckoff, Emily Steel, Emmet Robinson, and George Potts.[2]

Agricultural work

During his early years, Henry was absorbed in agricultural experimentation, and by the age of 23 he had gained international notice for his work at the Scientific Agricultural Farm near Newark, New Jersey. His success there brought him offers of a directorship of the Agricultural Bureau at Washington, and the Chair of Agriculture at the University of Athens, Greece, both of which he declined. Instead, he founded the Westchester Farm School near Mt. Vernon, New York — a model farm for experimentation and agricultural education and the first American scientific school of agriculture. Here, he conducted experiments with sorghum and published his first book, Sorgho and Imphee, the Chinese and African Sugar Canes, which became a school textbook and has been reprinted as recently as 2000.

Considered an agricultural expert by age 26, Olcott was again the recipient of many offers in that field, including an invitation to join a government botanical mission. He declined these offers, however, and traveled to Europe to study agricultural methods and developments. His report was published in the American Cyclopedia. Upon his return to America he became Associate Agricultural Editor of the New York Tribune, which position he held until 1860.

Marriage

On April 26, 1860, he married Mary Epplee Morgan, of New Rochelle, New York, daughter of the Reverend Richard U. Morgan, rector of Trinity parish in that city. Their children were Richard Morgan, William Topping, Henry Steel (Jr.)., and Bessie. The last son died in infancy, and Bessie lived only two years.[3] The older two sons grew to adulthood and were very close to their father, visiting his law office and corresponding when he was away.

Military service

While working as Associate Agricultural Editor of the New York Tribune, he was American correspondent of the Mark Lane Express, London. In 1859, while reporting the hanging of John Brown, the abolitionist, for the Tribune, Olcott was arrested as a spy and condemned to death. However, he was released upon his appeal to his captors under the seal of confidence as a Freemason.

In 1862, he enlisted in the Northern Army and fought through the North Carolina campaign under General Burnside. Continuing in the Northern army after that campaign, he became ill and was sent to New York for recuperation. Colonel Olcott possessed extraordinary courage, both physical and moral, and it was during this period of his life that this characteristic began to show itself strongly.

When he was well enough, instead of returning to active service in the army, the government asked him to conduct an inquiry into suspected frauds at the New York Mustering and Discharging Office. For four years, in the face of the most active opposition, Olcott continued this investigation despite threats, false accusations, and offers of bribes. At the end of that time, he had secured enough evidence to result in the conviction of the leading criminal, who was sentenced to ten years imprisonment and also the dismissal of others implicated. For this service, he received a letter of recognition from Secretary Stanton stating that his service was "as important to the Government as the winning of a great battle".

Now, the War Department, and two years later, the Navy Department asked for Colonel Olcott's services in like capacity. In both of these appointments he distinguished himself, receiving again the highest praise from the heads of both departments and the added comment, "That you have thus escaped with no stain upon your reputation, when we consider the corruption, audacity and power of the many villains in high position whom you have prosecuted and punished, is a tribute of which you may well be proud"[4]. Colonel Olcott had been admitted to the bar in 1868, and at the end of his government service, he entered private practice. Among his clients were many of the large corporations of the country.

Meeting H. P. Blavatsky

During all of these years, Colonel Olcott had been interested in Spiritualism, and in 1874 he was asked to take a special assignment for the New York Graphic to report the psychic phenomena at the Eddy farm in Vermont. As a result of this experience, he published his second book, People From the Other World.

It was at Chittenden, Vermont, while he was on this assignment, that he met H. P. Blavatsky who had come there on instructions from her Master. Joining forces with her, from this point onward he worked to carry out the purposes of the Brotherhood of Adepts, especially those purposes related to the specific mission assigned to Mme. Blavatsky by her Master. "Bound together by the unbreakable ties of a common work—the Masters' work—having mutual confidence and loyalty and one aim in view, we stand or fall together…"[5].

Of their personal relationship, Colonel Olcott says, "Neither then, at the commencement, nor ever afterwards had either of us the sense of the other being of the opposite sex. We were simply chums; so regarded each other, so called each other."[6] And again, "She looked at me in recognition at the first hour, and never since has that look changed . . . It was teacher and pupil, elder brother and younger, both bent on the one single end, but she with the power and the knowledge that belong but to lions and sages".[7]

President of the Theosophical Society

When the Theosophical Society was founded a year later in 1875, Colonel Olcott was elected president for life. From that time until the end of his life, the Society was his first care. He guarded it jealously from every threat to its existence; he gave his physical strength and the benefit of his wide experience to its organization, and his administrative ability to nourish it and foster its growth. For he believed with his whole heart that the good of mankind depended upon a channel through which the Brotherhood of Adepts could work to destroy the gross materialism of the day and awaken the spiritual nature of man. To this end, after the founders moved to India in 1878, he traveled through India and Ceylon in the interests of the Society, lecturing on Theosophy, trying to get people to see that they could live together in understanding and brother-hood, despite the difference of religious background and race.

He traveled all over Europe, England, South America, back to the United States three times, China, and Japan. With the exception of South America, he visited these countries again and again. Dr. Annie Besant said at the time of his death, "He traveled all the world over with ceaseless and strenuous activity, and doctors impute the heart failure, while his body was splendidly vigorous, to the overstrain put on the heart by the exertion of too many lectures crowded into too short a time."[8] In the Olcott Centenary issue of The Theosophist, August 1932, there are seven and a half pages given to the listing of his travels in the interest of the work.

When, in 1878, they moved the international headquarters to India, Colonel Olcott had to relinquish his flourishing law practice; and in 1882, when the headquarters was established at Adyar, that property was purchased almost entirely from his own and Mme. Blavatsky's funds. In fact, in the early years in India, the Society and the expense of lecture tours was supported primarily by the earnings from their writings and lectures.

During the years of his Presidency, he stood unflinchingly through many upheavals and tribulations suffered by the Society. He stood staunchly by HPB through all of the attacks upon her, though he often felt forced to place the Society's good before the defense of her reputation. Where he was mistaken in his attitude, he was always willing to admit his error and reverse his position when his Master made the issue clear to him. "He is one who never questions, but obeys; who may make innumerable mistakes out of excessive zeal, but never is unwilling to repair his fault even at the cost of the greatest self-humiliation..."[9]

Colonel Olcott had to pilot the Society without the stimulus of Mme. Blavatsky’s spiritual teaching for sixteen years after her death. He bravely continued the work for human brotherhood and understanding, and built the organization of the Society into an increasingly useful channel for the Masters to use in Their work for the world. He gave everything, his devotion, his health, his energy, his worldly goods, and family ties to Them gladly, as he had done from the beginning.

The Leaders of the Theosophical Society seem to be notable for their courage, and Colonel Olcott was no exception in that respect, meeting every disturbing element, every grave and often seemingly disastrous issue fearlessly, with the determination to bring the Society through with its strength undiminished. Numerically, this was not always accomplished; but spiritually the Society grew in strength as the Truth behind it was ultimately revealed after each time of turmoil. Crises were frequent and often shocking during the early years because they centered on Mme. Blavatsky, who was a complete mystery to the world at large, a mystery that could not be explained in terms acceptable to the world. Because of her relation to her Master, she was like a Secret Service man whose actions can never be wholly explained to others; and often even Colonel Olcott himself was not permitted to know the full truth about her. Yet, in the face of this, it was his responsibility to support her and at the same time, to resolve each situation to the best interests of the Society. This he did with characteristic honesty and fairness and great courage.

H. P. Blavatsky on Olcott leadership

Truth does not depend on the show of hands; but in the case of the much abused President-Founder it must depend on the show of facts. Thorny and full of pitfalls was the steep path he had to climb up, alone and unaided, for the first years. Terrible was the opposition outside the Society which he had to build; sickening and disheartening the treachery he often encountered within the Headquarters ; enemies gnashing their teeth in his face around ; those whom he regarded as his strongest friends and co-workers betraying him and the cause on the slightest provocation. Still, where hundreds in his place would have collapsed and given up the whole undertaking in despair, he, unmoved and unmovable, went on, climbing up and toiling as before, unrelenting and undismayed, supported by that one thought and conviction that he was doing his duty towards Those he had promised to serve to the end of his life. There was but one beacon for him—the hand that had first pointed to him his way up, the hand of the Master he loves and reveres so well, and serves so devotedly.

President, elected for life, he has nevertheless offered more than once to resign, in favour of anyone found worthier than he, but was never permitted to do so by the majority—not of ' show of hands ' but show of hearts, literally—as few are more beloved than he is, even by most of those who may criticise, occasionally, his actions. And this is only natural; for cleverer in administrative capacities, more learned in philosophy, subtler in casuistry, in metaphysics or daily-life policy, there may be many around him; but the whole globe may be searched through and through, and no one found stauncher to his friends, truer to his word, or more devoted to real, practical Theosophy, than the President-Founder; and these are the chief requisites in a leader of such a movement—one that aims to become a Brotherhood of men.[10]

Communications with the Mahatmas

Colonel Olcott had personal communication with several of the Mahatmas, including the Masters Morya, Koot Hoomi, Serapis Bey, Tuitit Bey, Hilarion, and Narayan. They regarded him highly as a faithful and reliable chela, and defended him from the anti-American criticisms of A. P. Sinnett and A. O. Hume. He was frequently mentioned in The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett. That volume includes two letters addressed to HSO – Mahatma Letter No. 103a and Mahatma Letter No. 110 – and two telegrams that the Colonel wrote – Mahatma Letter No. 115 and Mahatma Letter No. 116.

In Mahatma Letter Number 5, Mahatma Koot Hoomi wrote of H. S. Olcott,

Him we can trust under all circumstances, and his faithful service is pledged to us come well, come ill. My dear Brother, my voice is the echo of impartial justice. Where can we find an equal devotion? He is one who never questions, but obeys; who may make innumerable mistakes out of excessive zeal but never is unwilling to repair his fault even at the cost of the greatest self-humiliation; who esteems the sacrifice of comfort and even life something to be cheerfully risked whenever necessary; who will eat any food, or even go without; sleep on any bed, work in any place, fraternise with any outcast, endure any privation for the cause. [11]

Mahatma Letters to H. S. Olcott lists correspondence to the Colonel from six different Masters, in chronological order as nearly as it can be determined. These letters were addressed to him:

- 7 – published in Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom, First Series.

- 45 – published in Letters from the Masters of the Wisdom, Second Series.

- 1 – published in the Hodgson Report.

- 1 – published in the Beatrice Hastings book Solovyoff's Fraud and in Daniel H. Caldwell's volume A Casebook of Encounters with the Theosophical Mahatmas

Work with Buddhists and Buddhist schools

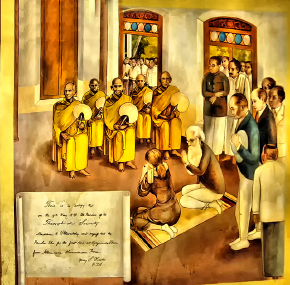

On May 19, 1880, at the invitation of two head Buddhist monks of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Col. Olcott, H. P. Blavatsky, and a group of Theosophists went to the island and "took Pansil", that is, they formally identified themselves with Buddhism by reciting the Five Precepts (pancha-sila) at the Vijayananda Vihara, in Galle. Col. Olcott certified this in his own handwriting:

"This is to certify that on the 19th May 1880 the Founders of the Theosophical Society Madame H. P. Blavatsky and myself took the Panchasila for the first time at Vijayananda Vihara from Akmemana Dhammarama Thera."

Sri Lanka was dominated by British colonial power and influence at the time. After making a public commitment to live by Buddhist precepts, Col. Olcott started his work to revive this religion, becoming instrumental in creating a renaissance in the study and practice of Buddhism. The effort to revitalize Buddhism within Sri Lanka was successful and influenced many native Buddhist intellectuals (including Anagarika Dharmapala), who found his interpretation of the Buddha's message socially motivating and supportive of efforts to overturn colonialist efforts to ignore Buddhism and Buddhist tradition.

Olcott united the Buddhist sects of Ceylon [now Sri Lanka], and later united the twelve sects of Japanese Buddhists into a joint committee for promotion of Buddhism. He brought the Burmese, Siamese, and Sri Lankan Buddhists into a Convention of Southern Buddhists; and formulated the Fourteen Propositions of Buddhism, a document which was the basis upon which the northern and southern Buddhists were united:

These two divisions ... did not condemn each other, but they rather gravely doubted whether the others were not taking a long way around to Nirvana... The Colonel went to work and drew up an outline of agreement, a sort of creed, containing fourteen points, and he obtained to this the signature of the high priests of Japan, who represented the Northern Church, and then the signatures of the leading men of the Southern Church, thus furnishing them with a common platform upon which they could agree, and enabling them to say that in important points they did agree... He obtained the consent of the Japanese priests to send each year some of their young students for the priesthood to study under the priests of the Southern Church, and he also got the priests of the Southern Church to send their young men to study under the direction of the Northern Church teachers. In this way, there presently arose a number of priests in both churches who knew both sides of the question, and in the end, peace and harmony must result.[12]

He was successful in getting the government to declare Wesak, the birthday of the Lord Buddha, a holiday. Before that came to pass, the government recognized only the Christian holidays and punished children who were absent from the missionary schools on their own religious holidays. "The Buddhists asked Colonel Olcott to help and he presented their case to the Colonial Secretary in London and gained redress. Full Moon Day of Wesak was made a government holiday in Ceylon and soon afterwards, a similar recognition was given to the principal Hindu festival.[13][14]

During his time in Sri Lanka Olcott strove to revive Buddhism within the region, while compiling the tenets of Buddhism for the education of Westerners. It was during this period that he wrote The Buddhist Catechism (1881), which was translated into at least twenty languages and 44 editions, and is still used today.

Olcott also acted as an adviser to the committee appointed to design a Buddhist flag in 1885. The Buddhist flag designed with his assistance was later adopted as a symbol by the World Fellowship of Buddhists and as the universal flag of all Buddhist traditions. Today this flag is flown in Sri Lanka and other Buddhist nations.

As a result of the great Buddhist revival which he began, three colleges and 205 schools were established, of which, 177 received government grants.

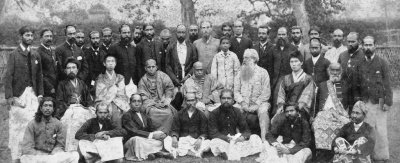

Olcott was also pivotal in the revival of Japanese Buddhism. He arrived in Kobe on February 9, 1889 together with Zenshiro Nogouchi and Anagarika Dharmapala. From the first day until his departure in May, Olcott visited 33 towns and delivered 76 addresses with a total audience of at least 87,500 people, and possibly as many as 200,000. With financial help from the Buddhist sects, and with support from Hansei-kai, Oriental Hall and other Buddhist societies, his tour became a great success. Olcott was welcomed by people everywhere, and he talked with local leaders and governors, as well as with the prime minister. Olcott’s tour was the peak of Japanese Buddhist revival in a visible form.[15][16]

In December, 1890, "Olcott convened at Adyar an unprecedented ecumenical convention of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhists from Ceylon, Burma, Japan, and Chittagong (now in Bangladesh)," with the goal of unifying the two schools of Buddhism. He aspired to form a "United Buddhist World."[17]

Olcott helped financially support the Buddhist presence at the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago, 1893. The inclusion of Buddhists in the Parliament allowed for the expansion of Buddhism within the West in general and in America specifically, leading to other Buddhist Modernist movements.

Work with Hindus and Hindu schools

Colonel Olcott did not confine his activities to strengthening the Buddhist religion alone. He worked zealously to revitalize the Hindu religion in India, and helped to establish many Hindu schools. He started the Olcott Harijan Free Schools (Children of God) for the benefit of the Panchama outcastes of India and in 1948 between 500 and 600 children were in attendance at the school near the Adyar compound.

For his interest and efforts on behalf of Hinduism, Colonel Olcott was adopted into the Brahman caste: "One striking evidence of the feeling of the India people towards us was the conferring upon me – doubtless as the official representative of the Society – of the Brahmanical sacred thread..."[18]

Work with Zoroastrians

He also was interested in the revival of the ancient Zoroastrian teachings, and his efforts bore much splendid fruit. Typical of his work for that religion is his fiery letter to K. R. Cama, who was one of the "best, wisest and most honorable" Parsi leaders of that time. That letter is a classic. In it, Colonel Olcott reproached the Parsis for being content with their wealth and modern culture and valuing so little their ancient teachings and the spirituality shown by the Parsis of old. He says:

They were led by the holy Dastur Darab whose purity and spirituality were such as to make it possible for him to draw from the boundless akash the divine fire of Ormuzd . . . Are you such men today with your wealth, your luxuries, your knighthoods, your medals and your mills? Have you a Darab Dastur among you, or even a school of the Prophets where neophytes are taught the divine science? . . . The question your humble friend and defender asks is whether you mean to keep idle and not stir a hand to revive your religion, to discover all that can be learnt about your sacred writings, to create a modern school of writers who shall invest your ethics and metaphysics with such a charm that we shall hear no more about Parsi men preaching Christianity . . . I believe not." He goes on to warn them of the dangers that threaten them as a result of their excessive worldliness and proceeds to make definite practical suggestions for the revival of their religion and their unique culture.[19]

Indian nationalist work

Soon after they came to India, Colonel Olcott organized the first exhibit of Indian products, and urged Indians to get together and use their own products instead of imports, and to develop an appreciation of them without regard to the religion or race of those who produced them. This was the beginning of Swadeshi, later adopted by the Indian National Congress.

Founding of Adyar library

Colonel Olcott founded the Adyar Library in December 1886, and invited representatives of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Islam to be present for its dedication ceremonies and bless the work. All accepted except the Christian clergy. This was the first time that representatives of these various religions had been brought together to participate in one meeting, and was considered a remarkable accomplishment on the part of the Colonel.

Healing work

One other activity which occupied Colonel Olcott in his early years in India was his energy healing work. He had great mesmeric healing power and was known all over India for effective cures. So many came to him for healing that it finally became necessary to ask the cooperation of the press to make it known that he would only treat such cases as received written permission to be brought to him. Eventually, he was instructed by his Master to cease that work, because of its drain on his own health and vitality and the fact that his energies must be conserved for the performance of his duties as President.

Freemasonry

"Colonel Olcott was a Freemason, and belonged to Huguenot Lodge No. 448, and was its Senior Warden in 1861. He was also in 1860 a member of the Corinthian Chapter, Royal Arch, No. 159. His diplomas are now in the Masonic Temple, Adyar."[20]

Writings

Colonel Olcott wrote numerous books, articles, and pamphlets that are listed in detail in ]]. Among his writings, the diary series called Old Diary Leaves is especially valued as a first-person account of the early days of the Theosophical Society. The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists 66 articles under the initials HSO, 760 under the name HS Olcott, 3 articles under H. S. Olcott, and 1 under Henry S. Olcott. In his work as a journalist, he also wrote for several New York newspapers.

Death

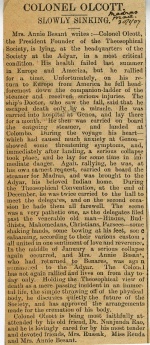

On October 3, 1906, while he was returning from the United States to Italy for a lecture tour, Colonel Olcott "met with a serious accident on board the steamer... As he was about to descend a stairway of fourteen steps leading to the lower deck his heel caught and he fell forward, 'end over end,' turning two complete somersaults and landing on his back at the bottom ... His escape from death was regarded by seven physicians and Surgeons on board ship, as being a miracle."[21] He was hospitalized in Genoa, Italy, and was expected to recover in three months, but died the following year, at the age of 74 on February 17, 1907, at the Adyar compound. He left a letter of farewell to his "brethren in the physical body" and of greeting to "my beloved brethren on the higher planes." (Image of letter is at left.)

Visit by the Masters

During Olcott's final month, his secretary, Marie Russak Hotchener, reported seeing the astral form of H. P. B., whom Olcott greeted as "Old Horse!"

On February 3 the Mahatmas paid one more visit to their old servant – the last during his conscious life on earth. The President's diary entry, in the handwriting of his honorary secretary, ready: "The Masters, all four, came this a.m., and told Col. his work was over. They thanked him for his loyalty and work in their interests. He was overcome with joyful emotion, jumped from his bed and prostrated himself at their feet." Mrs. Besant as well as Marie Russak seems to have been present on this occasion.[22]

Tributes

As Mr. C. Jinarajadasa has stated, "With HPB alone, there would have been Theosophy; but without Henry Steel Olcott, there would have been no world-wide Theosophical Society".[23]

And, greater still, the tribute paid him by the Master:

Where can we find an equal devotion? He is one . . . who esteems the sacrifice of comfort and even life something to be cheerfully risked whenever necessary; who will eat any food, or even go without; sleep on any bed, work in any place, fraternize with any outcast, endure any privation for the cause.[24]

Awards and honors

From 1934-1960, each annual convention of the Theosophical Society in America featured an Olcott Lecture selected from a competition. The first such lecture name "Dynamic Unity" was delivered by Sigurd Sjoberg.[25] In 1970, Joy Mills proposed renaming the American national headquarters library as "Olcott Library & Research Center"[26] Under John Algeo, the name was adjusted to take the current name, the Henry S. Olcott Memorial Library.[27] The entire headquarters campus has been known as "Olcott" since 1933. Other tributes to the Colonel are in the naming of the Olcott Foundation Awards; the Olcott Institute, an educational initiative during the administration of John Algeo; and the Olcott Gallery, an art display area in the L. W. Rogers Building.

Colonel Olcott is still remembered fondly by many Sri Lankans today. The date of his death is often remembered by Buddhist centers and Sunday schools in present-day Sri Lanka, as well as in Theosophical communities around the globe.

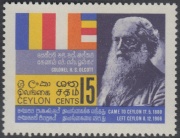

A stamp was issued by Dudley Senanayake, the then Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, on December 9, 1967, to honour Col. Olcott on the 60th anniversary of his death. Paying tribute to him on that occasion, the Prime Minister said: "at a time when Buddhism was on the wane in Sri Lanka, Col. Olcott came to Sri Lanka in May 1880 and awakened its people to fight to regain their Buddhist heritage...Col. Olcott can be considered one of the heroes in the struggle of our Independence and a pioneer of the present religious, national and cultural revival. Col. Olcott’s visit to this country is a landmark event in the history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka."[28]

In 1976, the United States Information Agency commissioned a color film about Colonel Olcott. Theosophist Dr. S. Krishnaswamy of Chennai, India and American Bill Bloom worked together to produce a biographical documentary entitled "Colonel Henry S. Olcott: Searcher After Truth."[29]

A fishing village near Adyar was named Olcott Urur Kuppam. Major streets in Colombo and Galle, in Sri Lanka, have been named Olcott Mawatha Road in his memory, along with Alcot Gardens, a residential district in in Rajahmundry, Andrah Pradesh.

Statues of the Founder have been erected in several places:

- Bust in front of the Adyar Library that he helped to establish.

- Statue in front of the Fort Railway Station in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on the south side of the Pettah, a busy commercial district.

- Statue at Maradana Railway Station in a suburb of Colombo.

- Statue in Galle, Ceylon city center.

- Statue near Princeton, New Jersey at the New Jersey Buddhist Vihara, unveiled on September 10, 2011 as a tribute by the Visakha Vidyalaya Old Girls Association.[30]

- Statue at Dharmaraja College, Kandy.

- Statue at Ananda College in Colombo.

Many schools in India and Sri Lanka honor Olcott as founder, with photographs and commemorative statues on display. His birthday is remembered at Olcott Memorial High School in Chennai, India: "Every year on February 17th, the OMHS higher wing students celebrate Colonel Henry Steel Olcott’s memory by singing songs while holding a procession carrying his portrait through the T.S."[31] Mahinda College in Galle, Ceylon has an auditorium named Olcott Hall. Ananda College in Colombo annually holds an Olcott Oration. Eight Buddhist schools of Sri Lanka annually conduct the Henry Steel Olcott Memorial Cricket Tournament.[32]

Additional resources

Biographies

- Murphet, Howard. Hammer on the Mountain: Life of Henry Steel Olcott (1832-1907). Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1972.

- Prothero, Stephen. The White Buddhist: The Asian Odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Articles and pamphlets

- "The Man Who Met the Masters: Colonel Henry Steel Olcott" by John Algeo

- "Olcott, Henry Steel (1832-1907" by John Algeo

- Colonel Henry Steel Olcott" by Annie Besant

- "Colonel Henry S. Olcott's Testimony about His Meetings with the Master Morya" by Daniel H. Caldwell

- "The Servant of the Masters - Col. Henry S. Olcott" by W. Q. Judge

- "The Powers of Truth and Discontent" by Anton Lysy

- "Henry Steel Olcott" by The Singapore Lodge Theosophical Society

- Olcott, Henry Steel in Theosophy World

Audio

- Olcott and Blavatsky: Theosophical Twins by John Algeo

Video

- Olcott and Blavatsky: Theosophical Twins by John Algeo

- Henry Steel Olcott: A Life of Service by John Algeo

- The Man Who Met the Masters: Henry Steel Olcott by John Algeo

- The Remarkable Life of Col. H. S. Olcott by Tony Lysy et al

Websites

- Astral Chart of Henry S. Olcott by Michael D. Robbins

- Quotes and articles by Henry Steel Olcott at Katinkahesselink.net

Notes

- ↑ Josephine Ransom, "Tributes" World Theosophy 2.8 (August, 1932), 642.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, The Descendants of Thomas Olcott (Albany, New York: J. Munsell, 1874), 99. This was a revised edition of the 1845 work by Nathaniel Goodwin.

- ↑ Henry Steel Olcott, The Descendants of Thomas Olcott (Albany, New York: J. Munsell, 1874), 106. This was a revised edition of the 1845 work by Nathaniel Goodwin.

- ↑ The Theosophist, August 1932, p. 475

- ↑ The Theosophist, August 1932, p. 471

- ↑ Olcott, H. S.Old Diary Leaves, vol. 1, p. 6

- ↑ Claude Bragdon, Episodes From an Unwritten History, p. 23

- ↑ Reminiscences of Colonel Olcott, p. 20

- ↑ The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett, p. 14

- ↑ W. A. English, "H. P. B.'s opinion of H. S. O. with an Introduction and Notes" The Theosophist (March, 1913): 939-940. Quoting Madame Blavatsky.

- ↑ Mahatma Letter No. 5, page 7.

- ↑ "The President-Founder and His Work in India",The Theosophic Messenger 2.5 (February 1901), 84.

- ↑ Gail Wilson, "Colonel Olcott" The Messenger 14.9 (February 1927), 190.

- ↑ Michael Gomes, "The Coulomb Case" Theosophical History Occasional Papers Volume X (Fullerton, California: Theosophical History, 2005) 2-3.

- ↑ Yoshinaga Shin’ichi, Theosophy and Buddhist Reformers in the Middle of the Meiji Period (Japanese Religions Vol. 34, No. 2, July 2009), 125.

- ↑ Stephen Prothero, The White Buddhist: the Asian Odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott(Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2010), 126.

- ↑ Prothero, 127.

- ↑ [Henry S. Olcott]. "The Sanskrit Revival" The Theosophist 7.6 (January, 1886), xxxvii.

- ↑ The Theosophist, 1932

- ↑ C. Jinarajadasa, The Golden Book of the Theosophical Society (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing Company), 153.

- ↑ "Accident to the President-Founder," Supplement to The Theosophist (November, 1906), xii.

- ↑ Howard Murphet, Yankee Beacon of Buddhist Light (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1988), 310.

- ↑ Introduction to The Original Programme of The Theosophical Society.

- ↑ Introduction to The Original Programme of The Theosophical Society (Adyar, Chennai, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), ??.

- ↑ Joy Mills 100 Yeas of Theosophy: A History of The Theosophical Society in America (Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House, 1987), 107.

- ↑ Joy Mills 100 Years of Theosophy: A History of The Theosophical Society in America (Wheaton, Ill.: Theosophical Publishing House, 1987), 172.

- ↑ John Algeo "President's Annual Report 1998" The Quest 86 no.10 (October, 1998): 4.

- ↑ "Remembering Colonel Henry Steele Olcott" The Island Online. Posted February 17, 2009, but is no longer available online.

- ↑ Film No. 52632. "Colonel Henry S. Olcott: Searcher After Truth." 1976. Records of the U. S. Information Agency. Record Group 306.6427. National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Description at http://research.archives.gov/description/52632.

- ↑ "Abdill, Ed. "Olcott Statue Unveiled in New Jersey". Theosophical Society in America web page. October 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Olcott's Vision." OMHS Newsletter March 2009. Available at OMHS website

- ↑ "Henry Steele Olcott Memorial Cricket Tournament" in Wikipedia.