Vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the theory and practice of voluntary abstinence from the consumption of any animal flesh (red meat, organ meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, and insects), and typically includes non-consumption of any other by-products of animal slaughter (such as animal rennet or gelatin). A vegetarian diet may consist of vegetables, fruits, seeds (legumes, nuts, grains), and other non-meat foods, such as fungi (mushrooms). While vegetarianism allows the consumption of animal products that are not directly derived from slaughter, such as dairy (milk, cheese), eggs, and honey, some people adhere to vegetarian diets that require the avoidance of these, or other foods, as well.[1][2]

Four common types of vegetarian diets exist. They are:

- Lacto-ovo-vegetarianism - Eats: dairy, eggs, & non-animal-based foods.

- Lacto-vegetarianism - Eats: dairy & non-animal-based foods, but not eggs.

- Ovo-vegetarianism - Eats: eggs & non-animal-based foods, but not dairy.

- Veganism - Eats: only non-animal-based foods. Many vegans also avoid animal products used in non-edible ways, such as leather, beeswax, wool, or silk.[3]

History

The origins of vegetarianism are uncertain, however, vegetarianism was practiced as early as 3200 B.C.E. by various ancient Egyptian religious groups. Other ancient philosophies also embraced vegetarianism, including Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and Brahmanism. Central to the beliefs of these traditions were the ideas of non-violence and respect for all life, as well as the experience that meat consumption hindered their spiritual and philosophical endeavors.[4] Many parallels exist between the beliefs of ancient vegetarians and modern vegetarians.

Vegetarianism was also prominent in ancient Greece, where its practice during the classical period was called "abstinence from beings with a soul" (Greek: ἀποχὴ ἐμψύχων). The Orphic religious practitioners abstained from the flesh of animals. Pythagoras taught that vegetarianism was important for peaceful human interaction because slaughtering animals damaged the soul. This practice was also advocated by Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Zeno (the founder of Stoicism), Seneca, Empedocles, Apollonius of Tyana, Plotinus, Porphyry (who wrote a treatise On abstinence from beings with a soul), and others.

Many early Christians were vegetarian such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and others, but this practice did not take hold among most followers. After the Christianization of the Roman Empire in late antiquity (4th-6th centuries) vegetarianism nearly disappeared from Europe until the Renaissance, where it reemerged. Leonardo da Vinci was among the first celebrities of the time who supported this practice.

Reasons for Vegetarianism

Vegetarians have several different motives for not eating animal flesh. Some are motivated by considerations of health, while others are concerned for the ecology of the Earth. Some adopt the diet for ethical or philosophical reasons, believing that animals have the right not to be harmed, while others use vegetarianism as part of a spiritual practice. Below is a brief description of some of these reasons.

Animal rights

One of the reasons for vegetarianism is based on a concern for "animal rights". This philosophical view does not propose equality between human and non-human animals. It maintains that rights are derived from the capacity to experience pain, and since animals experience pain just as human beings do, they have the right to be free from harm. Therefore, it claims that animals should be allowed to enjoy the most basic rights that all sentient beings desire: the freedom to live a natural life free from human exploitation, and the avoidance of unnecessary pain, suffering, and premature death.[5]

Some people oppose this idea arguing that rights are not derived from the capacity to experience pain but the ability to reason. Therefore, people have rights and animals do not.[6] However, this position is hard to justify because it would mean that babies (who cannot reason yet) or human beings with mental disabilities have no rights.

The underlying spirit in the concept of animal rights is that the lives of animals have their own purpose and do not exist to be useful to humans--whether for food, clothing, entertainment, experimentation, or any other reason.

Ecology

In 2006, a United Nations investigation found that raising livestock is one of the most damaging industries for the environment.[7] Livestock production uses 26 percent of all arable land for grazing, and food for industrial livestock takes up an additional one-third. Combined, livestock production uses more than half of all the available farmland on the planet, land which could be used to support at least 8 times as many people, possibly as much as 54 times, if it were used to grow grain crops.[8] In the U.S., 70% of all arable land is used to raise livestock.[9]

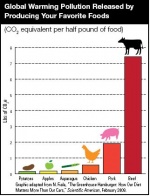

Grasslands and tropical forests are being destroyed at a rapid rate in order to increase available land for livestock feed and production. This deforestation and destruction contributes greatly to a loss of biodiversity. Additionally, the pollution, especially toxic runoff into water systems, causes great environmental damage. For instance, toxic runoff from industrial livestock production contributes significantly to the deadzone in the Gulf of Mexico. The deadzone encompasses 8,000 square miles of water in which there is too little oxygen for any significant life to survive. Further, livestock production accounts for 37% of methane emmissions, 65% of nitrous oxide emmisions, and 9% of all CO2 emissions. Methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than is carbon dioxide.[10]

Health

The China Study (a massive epidemiological study performed on populations in China) revealed that great differences in the prevalence of disease existed between areas which consumed animal products and areas which did not. As animal product consumption approaches zero, a dramatic decrease in cancer and other Western disease occurs. When strictly vegan, cancer and heart attacks, two of the leading causes of death in Westernized society, are nearly non-existent. Even slight consumption of animal products is associated with a significant increase in the prevalence of disease. Animal products are either low in or do not contain nutrients which protect against cancer such as antioxidants, fiber, phytochemicals, folate, vitamin E, and vegetable protein. Compounding this problem, animal products contain large amounts of cancer causing substances including saturated fat, IGF-1, arachidonic acid, and cholesterol.[11]

Cancer is not the only disease influenced by animal products. Coronary heart disease directly increases with the consumption of animal protein, and decreases as consumption of legume and vegetable protein increases. A strong correlation exists between vegetable and fruit consumption and general health.[12]

Vegetarianism and Theosophy

H. P. Blavatsky was not a strict vegetarian herself, although she always recommended the vegetarian diet for aspirants whenever that was possible (we must remember that at the end of the 19th century it was quite difficult to be vegetarian in the West). However, there are evidences that she did follow this diet at some periods, and that she intended to make it a rule in the Theosophical Society. For example, in a letter to her sister Madame Zhelihovsky, she wrote about a spiritual experience she had after following some ascetic practices, including vegetarianism:

In our Society everyone must be a vegetarian, eating no flesh and drinking no wine. This is one of our first rules. It is well known what an evil influence the evaporations of blood and alcohol have on the spiritual side of human nature, blowing the animal passions into a raging fire; and so one of these days I . . . resolved to fast more severely than hitherto. I ate only salad and did not even smoke for whole nine days, and slept on the floor. . .[13]

There are other mentions to the occult fact that the "evaporations" or "emanations" created by meat consumption generates an atmosphere that is inimical for spiritual influences. For example, Master K.H. manifested an increased sensitivity to these conditions after a retreat where he is said to have taken a higher Initiation. When the International Headquarters of the Theosophical Society was in Bombay, the Master wrote:

Since my return I found it impossible for me to breathe—even in the atmosphere of the Headquarters! M. had to interfere, and to force the whole household to give up meat; and they had, all of them, to be purified and thoroughly cleansed with various disinfecting drugs before I could even help myself to my letters.[14]

However, in spite of the importance of a pure diet, this should not be taken as the only or the most relevant aspect of a spiritual life. As the Master wrote:

It is useless for a member to argue "I am one of a pure life, I am a teetotaller and an abstainer from meat and vice. All my aspirations are for good etc." and he, at the same time, building by his acts and deeds an impassable barrier on the road between himself and us.[15]

Mme. Blavatsky stated a similar concept:

[Eating meat] is no crime; it will only retard his progress a little; for after all is said and done, the purely bodily actions and functions are of far less importance than what a man thinks and feels, what desires he encourages in his mind, and allows to take root and grow there.[16]

Thus, what a person does, feels, and thinks is always more important than the diet he follows. However, what he eats and drinks may make the purification of his nature more or less difficult.

Theosophical reasons

Although vegetarianism is not a requirement for membership in the Theosophical Society many of its members are vegetarians, and Theosophical principles encourage this way of life.

In her article "Have Animals Souls?" Mme Blavatsky supports vegetarianism as an act of compassion for the animals.[17] She also pointed out that meat consumption is an important cause of ill-health:

We believe that much disease, and especially the great predisposition to disease which is becoming so marked a feature in our time, is very largely due to the eating of meat, and especially of tinned meats. But it would take too long to go thoroughly into this question of vegetarianism on its merits.[18]

In most of her writings, however, she focused on the pernicious effect that eating meat has for the occult development of the aspirant:

The eating of meat strengthens the passional nature, and the desire to acquire possessions, and therefore increases the difficulty of the struggle with the lower nature.[19]

When the flesh of animals is assimilated by man as food, it imparts to him, physiologically, some of the characteristics of the animal it came from. Moreover, occult science teaches and proves this to its students by ocular demonstration, showing also that this "coarsening" or "animalizing" effect on man is greatest from the flesh of the larger animals, less for birds, still less for fish and other cold-blooded animals, and least of all when he eats only vegetables.[20]

Master K.H. stated that eating meat attracts impure entities and elementals. This becomes an important hindrance in the case of sensitives and mediums:

Both Maitland and herself [ Anna Bonus Kingsford ] as well as their circle — are strict vegetarians, while S.M. is a flesh-eater and a wine and liquor drinker. Never will the Spiritualists find reliable, trustworthy mediums and Seers (not even to a degree) so long as the latter and their “circle” will saturate themselves with animal blood, and the millions of infusoria of the fermented fluids.[21]

A number of Theosophists have supported vegetarianism as part of the spiritual life. Below are a number of reasons put forward by some prominent members of the Theosophical Society (Adyar):

- Interconnection with other Kingdoms of Nature

According to Theosophy life, in all its variety, is one. We are all connected, not only with other human beings but with the whole planet and even the cosmos. Animals are therefore seen as humanity's less evolved siblings. Being in a position of power, humans should aid creatures that are lower in the chain of evolution instead of causing them pain and misery. Because of this deep interconnection a person cannot advance and grow in isolation from the rest of the world. According to Annie Besant, the pain and disharmony of other sentient beings will eventually hinder his progress:

The misery that you cause is, as it were, mire that clings round your feet when you would ascend; for we have to rise together or to fall together, and all the misery we inflict on sentient beings slackens our human evolution, and makes the progress of humanity slower towards the ideal that it is seeking to realize.[22]

When animals are slaughtered filled with pain and fear they send out a powerful, negative vibrations into the astral plane, which subsequently influences the material world. Any person who comes near these vibrations is also influenced by them, the sensitive being especially susceptible. Again, in Annie Besant's words:

This continual throwing down of these magnetic influences of fear, of horror, and of anger, and passion, and revenge, works on the people amongst whom they play, and tends to coarsen, tends to degrade, tends to pollute.[23]

C. W. Leadbeater explains it similarly, stating that the pain and terror inflicted upon the animals butchered for our consumption is creating unseen, yet strong, forces which negatively affect us and our children, creating an atmosphere of fear and terror.[24]

- The building of the subtle bodies

The body is seen as the vehicle for the soul. It needs to be kept in as best of a condition as possible so that it is easier to develop the higher and more important aspects of our nature. A diet based on animal meat makes it more difficult for the soul to use its vehicles. Annie Besant wrote:

As we carry on the purification of the physical body by feeding it on clean food and drink, by excluding from our diet the polluting kinds of aliment - the blood of animals, alcohol and other things that are foul and degrading - we not only improve our physical vehicle of consciousness, but we also begin to purify the astral vehicle and take from the astral world more delicate and finer materials for its construction. The effect of this is not only important as regards the present earth-life, but it has a distinct bearing also . . . on the next post-mortem state, on the stay in the astral world, and also on the kind of body we shall have in the next life upon earth. [25]

C. W. Leadbeater explains further how the constitution of the physical body affects the subtle bodies:

As the astral body is the vehicle of the emotions and passions, it follows that a man whose astral body is of the ruder type will be chiefly amenable to the lower and rougher varieties of passion and emotion; whereas a man who has a finer astral body will find that its particles most readily vibrate in response to higher and more refined emotions and aspirations. Thus a man who is building for himself a gross and impure physical body is building for himself at the same time coarse and unclean astral and mental bodies as well. This effect is visible at once to the eye of the trained clairvoyant, and he will readily distinguish between a man who feeds his physical vehicle with pure food and another who contaminates it by intoxicating drink or decaying flesh.[26]

- Responsibility

Although animals are not necessarily being killed directly by meat-eaters, the Theosophical approach maintains that people eating meat are still responsible for the “deterioration in the moral character of the men on whom we throw this work of slaughtering”.[27] Geoffrey Hodson explains that forcing people to work in the meat processing industry is cruel. The industry causes people to lose their appreciation for life, and tends to derail their spiritual and cultural progress.[28]

According to Annie Besant, an ethical rule is that no person should force another person to perform some duty that he or she is not willing to perform his or her self. If a person wants to eat meat, they should do the killing themselves.[29] Leadbeater strongly agrees with this sentiment, writing "It is universally recognized in law that qui facit per alium, facit per se--whatsoever a man does through another, he does himself."[30]

Vegetarianism in practice

Although vegetarianism is not a requirement for membership in the Theosophical Society, many Theosophists have lead purely vegetarian diets, or move toward vegetarianism since the founding of the Society.

Anna Kingsford was an early advocate of vegetarianism. She graduated from a Paris university in 1880, one of the first women to graduate with a doctorate in medicine, so that she could argue for vegetarianism with more credibility. Her beliefs were very much in accordance with Theosophy, and she became president of the London Lodge of the Theosophical Society in 1883.

Dr. Kingsford's belief was that as creatures more evolved than animals we should uphold a corresponding, higher moral quality of truthfulness, love, sympathy, and friendship. She believed that being human in form is less important than being human in spirit, and that as higher creatures, we should not mistreat and kill needlessly other creatures. Much like other prominent Theosophists, she believed that ultimately speaking, all creatures are one.

Dr. Annie Besant was also an important advocate of vegetarianism. The souvenir book produced for the 1957 International Vegetarian Union Congress features some of her writings under "History of Vegetarianism."[31]

Theosophist Geoffrey Hodson was the founder and long-serving President of the New Zealand Vegetarian Society, while the Indian Vegetarian Congress was founded by Rukmini Devi Arundale in 1959, of which she served as President for many years.[32] She was quoted as saying:

We always speak of rights of man and the freedom of the individual, but we forget that besides his rights, man has his responsibilities as well. These responsibilities do not merely extend to the poor and the suffering in the human kingdom, but also to the animal kingdom, which is even more helpless and in need of kindness and compassion. Surely, every living creature has its own right to happiness, and although it is true that there is so much cruelty and sorrow in nature, still there are many compensations and no cruelty in nature can equal that which is perpetrated by man.[33]

A number of facilities operated by and conferences held by Theosophical groups generally offer ovo-lacto-vegetarian meal service, often with vegan options. Examples are the Adyar campus of the Theosophical Society in India, the Olcott campus of the Theosophical Society in America, the Krotona Institute, Point Loma, the International Theosophical Centre at Naarden in The Netherlands, and Mt. Helena Retreat Centre of Theosophy in Perth, Australia. Members of the Esoteric Section always practice vegetarianism.

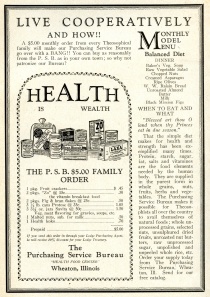

In the 1920s, the American Theosophical Society under President L. W. Rogers created a Purchasing Service Bureau in its Wheaton, Illinois headquarters to offer products that supported a vegetarian diet. The Society combined popular items into convenient packages like the $5.00 Family Order shown in the advertisement at the right. Protose meat substitute, Savita yeast extract, Zo breakfast cereal, and other products came from the Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Foods, developed by John Harvey Kellogg.

During World War II, when meat was rationed in the United States, Theosophists provided vegetarian recipes to local newspapers in an effort to facilitate change of diet. After the war, American Theosophists shipped thousands of parcels of peanut butter, cheeses, and other vegetarian foods to European members who needed sources of protein in their meatless meals.

Over the years Theosophists have written numerous vegetarian cookbooks. One of the earliest was Practical Vegetarian Cookery, edited by the Countess Wachtmeister and Kate Buffington David, published by Mercury Publishing Company in 1897.

Other resources

List of vegetarian activists

Articles and pamphlets

The Union Index of Theosophical Periodicals lists over 170 articles with "vegetarian" in the title, reflecting interest in the subject from the 1880s to the present. Some articles and pamphlets are available online:

- Vegetarianism in the Light of Theosophy by Annie Besant

- Theosophic Diet by W. Q. Judge

- Theosophical Vegetarianism in Australia by Edgar Crook, published online by the International Vegetarian Union.

- Vegetarianism and Occultism by C. W. Leadbeater

- Empirical Vegetarianism by W. Wybergh

- Vegetarianism and Theosophy by The Theosophical Society in America

- New study reveals ancient Egyptians were mostly vegetarian at Ancient-Origins.net

- How Vegetarian Food Fueled the British Suffragette Movement by Anne Ewbank.

Books

- Porphyry, On abstinence from animal food - Introduction, Book 1, Book 2, Book 3, and Book 4 Translated by Thomas Taylor

Videos

- Vegetarianism and Spirituality by Pat Davis

Notes

- ↑ What is a vegetarian? by The Vegetarian Society

- ↑ Why Avoid Hidden Animal Ingredients? by The North American Vegetarian Society

- ↑ Types of Vegetarianism by Vegetarian Nation

- ↑ World History of Vegetarianism by Vegetarian Society.

- ↑ See Primer on Animal Rights at the Vegetarian Resource Group website

- ↑ See Animal Rights And Vegetarianism at the Atlas Society website

- ↑ Livestock a major threat to environment by Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN.

- ↑ Science News by Cornell University: "U.S. could feed 800 million people with grain that livestock eat, Cornell ecologist advises animal scientists."

- ↑ Marlow Vesterby et al., Major Uses of Land in the United States, Resource Economics Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Statistical Bulletin No. 973.

- ↑ Harmful Environmental Effects Of Livestock Production On The Planet Increasingly Serious at ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Joel Fuhrman, Eat to Live: The Revolutionary Formula for Fast and Sustained Weight Loss (New York: Little, Brown and Co., [2005]), 70.

- ↑ Joel Fuhrman, Eat to Live: The Revolutionary Formula for Fast and Sustained Weight Loss (New York: Little, Brown and Co., [2005]), 71.

- ↑ William Quan Judge, "Letters of H. P. Blavatsky - I", The Path, 9:9 (December 1894), 268-269

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 49 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 138.

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 30 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 95.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Key to Theosophy (London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1968), 261.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. VII (Adyar, Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1958), 12-49.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Key to Theosophy (London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1968), 261.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Collected Writings vol. XII (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), 496.

- ↑ Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, The Key to Theosophy (London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1968), 260.

- ↑ Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in chronological sequence No. 49 (Quezon City: Theosophical Publishing House, 1993), 138.

- ↑ Annie Besant, Vegetarianism in the Light of Theosophy, Adyar Pamphlet No. 27 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1932), 19.

- ↑ Annie Besant, Vegetarianism in the Light of Theosophy, Adyar Pamphlet No. 27 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1932), 13-15.

- ↑ Charles Webster Leadbeater, Vegetarianism and Occultism, Adyar Pamphlet No. 33 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1913), 34.

- ↑ Annie Besant, Man and His Bodies (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1909), 44-45.

- ↑ C. W. Leadbeater, The Hidden Side of Things (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974), 349.

- ↑ Annie Besant, Vegetarianism in the Light of Theosophy, Adyar Pamphlet No. 27 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1932), 15.

- ↑ Geoffrey Hodson, The Case for Vegetarianism (Auckland: The New Zealand Vegetarian Society, ca.1940), 4-5.

- ↑ Annie Besant, Vegetarianism in the Light of Theosophy, Adyar Pamphlet No. 27 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1932), 15.

- ↑ Charles Webster Leadbeater, Vegetarianism and Occultism, Adyar Pamphlets No. 33 (Adyar, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House, 1913), 22.

- ↑ History of Vegetarianism by International Vegetarian Union (IVU).

- ↑ Indian Vegetarian Congress Website http://www.vegcongress.org/, accessed February 29, 2012.

- ↑ Shakuntala Ramani, ed., Rukmini Devi Arundale: Birth Centenary Commemorative Volume (Chennai, India: The Kalakshetra Foundation, 2003), 204.