Education and the Theosophical Movement: Difference between revisions

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Following the English example, Besant founded the Theosophical Educational Trust in India. She was the Trust president, and [[Ernest Wood]] became the secretary. He became principal of the school at Madanapalle and late at .... By 1914 there were fifteen schools under the management of the TET in India. Wood said the Trust's purpose was: | Following the English example, Besant founded the Theosophical Educational Trust in India. She was the Trust president, and [[Ernest Wood]] became the secretary. He became principal of the school at Madanapalle and late at .... By 1914 there were fifteen schools under the management of the TET in India. Wood said the Trust's purpose was: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

not to teach Theosophy, but to provide a more balanced education, which should awaken the emotions of the students along social and spiritual lines, and not confine itself to the intellect as was the prevailing mode.<ref>Ernest Wood | not to teach Theosophy, but to provide a more balanced education, which should awaken the emotions of the students along social and spiritual lines, and not confine itself to the intellect as was the prevailing mode.<ref>Ernest Wood, ''Is This Theosophy?''(London: Rider & Co., 1936), 199.</ref> | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 14:57, 4 December 2024

Education has long been a focus of attention in most branches of the international Theosophical Movement.

Educational initiatives of the early Theosophical Society

Buddhist schools

The earliest involvement of the TS with education was in 1886, when the Society's president, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott began establishing schools in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), working with Sri Sumangala Thero. At that time, English missionaries dominated the educational options on that island. Buddhism was severely repressed, and many poor children had no access to schools. Olcott worked with local Buddhists to build schools, and brought in American, British, and Australian Theosophists to help organize them. He left a legacy of about 200 Buddhist schools in Ceylon, where he is a national hero. These schools were grounded in the local language, religion, and culture rather than trying to dispense Theosophy. Olcott was aiming to provide a service, not to proselytize. These are some of the most prominent schools that are still in operation:

- Ananda College was founded on November 1, 1886 in the capitol city of Colombo. In over 130 years of operation, the school has nurtured generations of leaders for Sri Lanka, with with 8,000 boys in 13 grades. It was named after a chief disciple of Gautama Buddha.

- Mahinda College in Galle is another boys' school that has been hugely successful since its founding in 1893. Francis Lee Woodward was an early principal, and by 1907 had led a major expansion with construction of the main building that is still in use.

- Musaeus College is a girls' school, founded in 1891 in Colombo by Marie Musaeus-Higgins with help from Peter de Abrew and Wilton Hack, and Dr. W. A. English. Student enrollment is now over 6,700, with a staff of over 300 teachers

Panchama schools

Colonel Olcott was also concerned about the outcastes in India known as panchamas, dalits, harijans, or paraiyars (pariahs). Olcott established 5 schools in South India. Initially staff members were Westerners, because Hindu teachers considered the students to be untouchable. Several of the schools were taken over by the government. The Olcott Memorial High School, established in 1894 as the Olcott Harijan Free School, continues serving children at the international headquarters in Adyar.

Hindu schools

Olcott establishing many Hindu schools in India, joined by many American and British Theosophists in parallel with his efforts in Ceylon. After he died in 1906, Annie Besant, his successor as president, carried on this work. She was very active in the Indian independence movement, and saw education as a high priority for creating generations of Indians who could bring their country into full equality with other nations in the modern world. She wrote:

The great aim of our education is to bring out of the child who comes into our hands every faculty that he brings with him, and then to try to win that child to turn all his abilities, his powers, his capacities, to the helping and serving of the community of which he is a part.

Mrs. Besant founded Central Hindu College in Benares (Varanasi) in 1898, along with its associated schools for boys and girls, and headed that initiative for 16 years.

Educational approach of early Theosophist-supported schools

These early school generally followed this approach:

- Native religious traditions were preserved or restored.

- Education was facilitated for girls and lower castes as well as boys.

- All religions, castes, and cultures were treated with respect.

- Native-born teachers taught religion, language, and arts suitable to the local population, while

- Western teachers offered modern educational methods, and taught sciences and business practices.

- Nationalism was encouraged, but along peaceful lines.

Educational initiatives of TS, Adyar

The Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Chennai, India has been the largest contingent of the Theosophical Movement for the past century, and its members have been responsible for many educational initiatives.

Theosophical Educational Trust

After hearing George S. Arundale speak about "Education as Service" at the 1912 annual convention of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, English Theosophist Ada Hope Russell Rea worked to establish the Theosophical Educational Trust in England. Annie Besant endorsed the concept in a letter to Trust secretary Josephine Ransom in 1913. The Garden City Theosophical School was opened in Letchworth, Hertfordshire, in 1915; the name was changed to Arundale School and later to St. Christopher School. Several other schools in England and Wales were affiliated with the Trust.

Following the English example, Besant founded the Theosophical Educational Trust in India. She was the Trust president, and Ernest Wood became the secretary. He became principal of the school at Madanapalle and late at .... By 1914 there were fifteen schools under the management of the TET in India. Wood said the Trust's purpose was:

not to teach Theosophy, but to provide a more balanced education, which should awaken the emotions of the students along social and spiritual lines, and not confine itself to the intellect as was the prevailing mode.[1]

Society for the Promotion of National Education

The Society for the Promotion of National Education (SPNE) was an organization established in 1916 in India to support the development of schools based in Indian languages, religions, and customs. on December 27, 1916, the Theosophical Educational Trust, at its annual meeting, "resolved to make a present to the Society of its colleges and schools as far as possible." TS President Annie Besant was given authority to determine when and how the educational institutions should be transferred to the governance of the Society.

Staff and members of the Theosophical Society based in Adyar, Madras (now Chennai), India were heavily engaged in every aspect of SPNE's operation, although the two organizations were not legally connected. The participants were motivated by the desire to serve the Indian people and to prepare India to prepare for independence.

In 1924, the SPNE closed, and schools were merged back into the Theosophical Educational Trust.

Theosophical Fraternity in Education

The New Education Fellowship was an international organization dedicated to the ideals of progressive education. It was established in 1921 by Theosophist Beatrice Ensor, founder of a progressive school in Letchworth, England, along with several colleagues. The fellowship spread its philosophy through such journals as "The New Era" (now "The New Era in Education") in England and Progressive Education in the United States.[2] It is now known as the World Education Fellowship.

In 1947 Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa wrote a brief account of an English organization, the Theosophical Fraternity in Education:

There is to-day a great movement called the New Education Fellowship. It has spread to most of the countries in Europe, and also to North America, and nearly all distinguished leaders of education are among its principal officers, or on its committees. It publishes a review in three languages. It has held its congresses in the principal capitals of Europe, and its two last congresses were in South Africa and Australia. But this powerful movement for the ideals of New Education began with a band of Theosophists in England, who created the "Theosophical Fraternity in Education." A few rich Theosophists then poured thousands of pounds into experimental schools in connection with this work of the Fraternity. To-day, in India, the Theosophists have New Education Schools in several places; there is a school in Australia, another in New Zealand. In fact, one of the first results of our study of Theosophy is to understand the child from a new standpoint.[3]

In the United States, the School of the Open Gate was affiliated with the Fraternity.

Raja Yoga schools and Point Loma education

Katherine Tingley was the charismatic leader of a large branch of the Theosophical Movement called Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society. She and other Theosophists established a Raja Yoga school for children in 1900 at their colony in Point Loma, near San Diego. Other Raja Yoga schools operated briefly in Germany, Sweden, Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Cuba. Madame Tingley said:

I called the college Raja Yoga because that means the kingly union of mental, spiritual, and physical development, aimed to return to the pure ideal of Greek simplicity... A child at Point Loma is taken as a precious, wonderful entity and is developed as such.

Educational approach

This is the educational approach of the Raja Yoga schools:

- School focused on intellectual formation and moral and spiritual development.

- Boys and girls followed the same curriculum, which was unusual in those days, but were separated except in music classes.

- Art, music, drama, and crafts were especially emphasized. All children learned to play musical instruments.

- The school was residential, and even children whose families lived in the Lomaland colony also boarded with classmates.

- Children spent a great deal of time outdoors.

School of Antiquity

School of Antiquity was the popular name of the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity or SRLMA. It was an educational enterprise established at Point Loma by Katherine Tingley. The cornerstone of the school was laid February 23, 1897. Stones were collected from locations of psychic or energetic significance in Ireland, Holland, Austria, Switzerland, and elsewhere at Madame Tingley's direction, and were used in the foundation of the building. These stones were supposed to bind together ancient sites with the new temple in Point Loma.[4]

Theosophical University

A Theosophical University followed in 1919, teaching liberal arts, Sanskrit, science, philosophy, and Theosophy. Its Theosophical University Press publishes Theosophical books of high quality in several languages, and offers many works free on its website.

Rudolf Steiner and Waldorf education

Rudolf Steiner was active in the Theosophical Society from 1902 for about ten years, heading its German Section, after which he formed the Anthroposophical Society. Dr. Steiner was a genius who made major contributions in many fields, from Goethe scholarship to architecture to agriculture. In 1919, the owner of the Waldorf Astoria Cigarette Company in Stuttgart, Germany invited Dr. Steiner to educate the children of factory workers and managers together, in the interest of peace and social justice. Steiner trained teachers and had all grades operating at the original Waldorf School in a matter of months, with a complete and cohesive theory of child development. He said of education:

Our highest endeavor must be to develop free human beings who are able of themselves to impart purpose and direction to their lives. The need for imagination, a sense of truth, and a feeling of responsibility—these three forces are the very nerve of education.

There are now more than 1,200 Waldorf schools and 1,900 Waldorf kindergartens around the world in over 80 countries. The United States, Germany, and the Netherlands are especially active in Waldorf education, with multiple training programs for teachers.

Educational approach

These are some of the elements of Waldorf education:

- Imaginative play is the work of young children.

- Reality is gradually introduced during the early years.

- Toys are objects made of natural materials designed to stimulate imagination, such as lengths of silk, wooden blocks, and plain dolls.

- The curriculum is concerned with developmental stages, unfolding consciousness, and age-appropriateness.

- Storytelling and fantasy are used to convey concepts.

- The atmosphere is one of beauty and harmony.

- Early cooperative activities foster social development.

- Emphasis is placed on the rhythms of the days and seasons.

- Children are engaged in a spiritual journey learning the inner realities of the physical world.

Montessori education

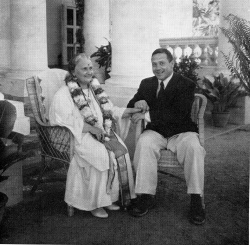

Dr. Maria Montessori was already well-established as an educator when she first met Annie Besant, president of the Theosophical Society, Adyar. Theosophists were very interested in Montessori education, and used its principles in a class at National Hindu Girls’ School in Madras, under the supervision of the Society for the Promotion of National Education. When World War II made Dr. Montessori's life in Italy too dangerous, TS president George S. Arundale invited her to reside at the Adyar headqarters of the TS in Madras (now Chennai), India. She and her son Mario used Adyar as their base of operations for ten years, conducting teacher training all over South Asia.

Worldwide, there are now almost 16,000 Montessori schools.

Educational approach

These are some elements of Montessori's educational approach:

- Fantasy is postponed until the child is grounded in reality.

- Tasks and activities are reality oriented.

- The intellect or "absorbent mind" is engaged early.

- Children are free to choose their own activities.

- Manipulative materials are designed to be aesthetically pleasing, and to support very specific educational goals.

- The atmosphere is calm and productive.

- Teacher is a facilitator of independent learning.

- Socialization begins with respecting the space of others.

- Older children voluntarily assist each other in learning.

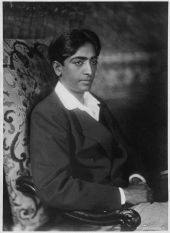

Krishnamurti education

As a young man in 1917, Jiddu Krishnamurti described "the life of an ideal school where love rules and inspires, where the students grow into noble adolescents under the fostering care of teachers who feel the greatness of their vocation."[5]

Educational approach

These are some principles applied in Krishnamurti schools:

- School focus is on the development of the whole human being.

- Students learn to observe the world and act in the world without conditioning or self-centeredness.

- The school tries to establish an environment in which this kind of education and self-development can take place.

- Faculty work together to develop themselves as human beings who are capable of maintaining the educational environment.

- There is no fixed curriculum or method.

Krishnamurti schools

Krishnamurti founded several schools:

- Rajghat Besant School, built in Varanasi, India in 1934.

- Brockwood Park School in Hampshire, England was established in 1969.

- Oak Grove School in Ojai, California, built in 1975.

- Rishi Valley Education Center.

- "The School" at Damodar Gardens in Chennai.

- Haridvanam in Bangalore.

- Sahyadri School in Pune.

- Pathashaala in Chennai.

He said,

The purpose, the aim and drive of these schools is ... to create the right climate so that the child may develop fully as a complete human being. This means giving him the opportunity to flower in goodness so that he is rightly related to people, things and ideas, to the whole of life.

During the 1940s he worked with Aldous Huxley, Robert Logan, the Rajagopals, and Dr. Guido Ferrando to develop the Happy Valley School on land purchased in 1926 by Annie Besant. This independent school does not necessarily follow the same educational approach as the others.

Theosophical schools

Theosophical schools have existed all over the world, for various lengths of time. Communities have come together to create special schools in Australia and New Zealand, in England, The Netherlands, Poland, Java (Indonesia), and The Philippines. Teacher training programs were established in several countries. In addition to the formal preschools and grade schools, Theosophical lodges have often conducted regular classes in Theosophy for members' children, such as Lotus Circles, comparable to Christian Sunday schools.

There have been several attempts at establishing Theosophical universities. Huge energy has always been put into adult education in many forms – classes at lodges, camps, and retreat centers; lessons in periodicals and newsletters; mail-order instruction; lessons for prisoners; webinars; and now the Online School of Theosophy.

Educational approach

Theosophical schools tend to be tailored to local populations, offering arts, crafts, and languages that are culturally appropriate. Activities of daily life are understood to be suffused with spiritual meaning. Self-awareness, meditation, yoga, and spiritual forms of the arts are usually taught.

The concepts central to Theosophy are subtly emphasized, such as:

- Unity of all life in a universe filled with energy and consciousness.

- Humans as energetic beings with a complex constitution.

- Spiritual evolution.

- Cyclicity of time.

- Interconnections of religion, philosophy, science, arts.

- Freedom of thought and belief.

- Responsibility for own spiritual development.

School initiatives

- Morven Garden School in Sydney, Australia.

- Vasanta Garden School in Auckland, New Zealand; opened on February 19, 1919.

- Arjuna schools in Java, Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Fifteen Arjuna schools were thriving in the 1920s and 1930s, with a teacher training academy, but most closed during World War II. One school remains active today.

- Theosophical schools in Poland, of which no details are available.

Apart from the establishment of individual schools, one initiative focused on curriculum and educational methods, headed by Theosophist Fritz Kunz. The Foundation for Integrative Education was a group of scientists, scholars, and businessmen who wanted to improve education by including philosophy, religion, and art with modern science in a cohesive curriculum. Kunz organized lecture series, conferences, and seminars exploring new ways to integrate knowledge so that students would experience interconnectivity and wholeness. The Foundation in turn gave rise to the Center for Integrative Education, which included stellar academicians such as Abraham Maslow, Henry Margenau, Kirtley Mather, F. S. C. Northrop, and Ervin Laszlo among its members. Kunz worked with his son John and others to establish the Cuisenaire Company as a provider of innovative materials for the teaching of mathematics.

Golden Link Schools

In 1986, Vic Hao Chin, a Theosophical leader in the Republic of the Philippines, established the first learning center leading to Golden Link College in 2002. The main campus at Caloocan City offers classes from preschool through collegiate courses. Other schools are located in:

- Cortes, Bohol

- Santa Maria, Bulacan

- Quezon City

- Philippine Lumen School, Bago City, Negros Occidental (affiliate)

- Alesna Integrated School, Lapu-Lapu City, Cebu (affiliate)

- TOS Learning Center, Caloocan City (affiliate)

Educational approach

These schools have successfully combined elements of Krishnamurti's teachings with Theosophy and government-mandated curriculum.

- Schools comply with requirements of the Philippine Department of Education and the Commission on Higher Education.

- Schools are nonsectarian.

- Students are never motivated by fear, ranking, and comparison.

- Freedom of thought and expression are encouraged.

- Development of personality and character is a central tenet, with emphasis on self-awareness, self-mastery, effective relationships, values integration, and related subjects.

- High school and college students participate in a self-transformation program.

- College students have courses in:

- Theosophy and the Perennial Philosophy

- Introduction to Philosophy

- Comparative Religion

- Marriage and Parenting

- Theosophical Education and Alternative Education Approaches (for Teacher Education students)

- Parapsychology and Transpersonal Psychology (for Psychology students)

Vic Hao Chin says,

It is important for a school to have teachers who are psychologically active, creative, and free. They themselves are not afraid to question things and hence tend to integrate their own understanding of life.

A wholesome school, then, must be able to prepare students to meet the demands of an adult life in terms of career, social skills, self-mastery, self-awareness, clarity of values, and an integrated philosophy of life.

Adyar Theosophical Academy

The Golden Link approach has expanded to India. The Adyar Theosophical Academy was established in 2019 in Besant Gardens at the Adyar headquarters of the Theosophical Society during the administration of Tim Boyd.

Educators in the Theosophical Movement

For a list of people who were educators in the Theosophical Movement, or who were influential to Theosophists, see Educators. Here are some of the most active teachers and organizers:

- In early Theosophical initiatives: Henry Steel Olcott, Charles Webster Leadbeater, C. Jinarājadāsa, Fritz Kunz, Marie Musaeus-Higgins, and Francis Lee Woodward.

- In SPNE: Annie Besant, George S. Arundale, Francesca Arundale, James H. Cousins, Margaret Cousins, Fritz Kunz, Ernest Wood, Mary K. Neff, C. Jinarājadāsa, Nilakanta Sri Ram, B. P. Wadia, Bhagavan Das, Hirendranath Datta, Sir S. Subramania Iyer, P. K. Telang, Frederick Gordon Pearce, and P. K. Subramania Iyer.

- In Point Loma's schools: Charles J. Ryan, Henry T. Edge, August Neresheimer, Geoffrey A. Barborka, and Grace Knoche.

- Professors who were prominent Theosophists: Jirah Dewey Buck, Seth Pancoast, J. Émile Marcault, José B. Acuña, I. K. Taimni, John Algeo, Ravi Ravindra, J. J. van der Leeuw, Charles Elliott Fouser, Oliver J. Schoonmaker, Manilal N. Dvivedi, and E. A. Wodehouse.

- Other educators who were prominent Theosophists: G. R. S. Mead, Felix Layton, Eunice Layton, Anna Kamensky, Pieter K. Roest, Anita Henkel, Joy Mills, Ianthe H. Hoskins, Emogene S. Simons, and Julia K. Sommer.

Additional resources

Articles

- Education and Theosophy at Theosopedia

- Education in the Light of Theosophy by Annie Besant

- Notes on Theosophy and Education by Bertram Keightley

- The Goal of Theosophical Education compiled by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Theosophical Education and the Golden Link College by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Readings on Theosophical Education compiled by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- C. W. Leadbeater's Work for the Buddhist Revival Movement in Sri Lanka, 1886-1889, compiled by Pedro Oliveira for his CWLWorld website. Much information about establishment of Buddhist schools by Theosophists.

Books

- Ransom, Josephine. Schools of Tomorrow in England. London: G. Bell and Sons, 1919. Available at Open Library and Internet Archive.

- Theosophical Education Chapter II in Thesis Dr Annie Besant and her contributions to society and politics 1893-1933 by Anthony Chaganti (See Table of contents).

- On Education by Vicente Hao Chin, Jr.

- Education as Service by J. Krishnamurti.

Video

- Education and the Theosophical Movement by Janet Kerschner. Presented NOvember 7, 2024 at the Theosophical Society in America.

Websites

Notes

- ↑ Ernest Wood, Is This Theosophy?(London: Rider & Co., 1936), 199.

- ↑ New Education Fellowship at The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (March 18, 2024)]

- ↑ Curuppumullage Jinarājadāsa, The New Humanity of Intuition (Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1947), 136-137.

- ↑ W. Michael Ashcraft, The Dawn of the New Cycle: Point Loma Theosophists and American Culture, (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2002), 48-49.

- ↑ Jiddu Krishnamurti, Education as Service, 1917. Mentioned by Mary Lutyens in Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 6.